Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

At Thirty-Three, My Anger Hasn't Subsided. It's Gotten

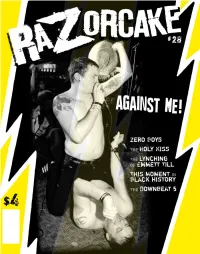

t thirty-three, my anger hasn’t subsided. It’s gotten And to all this, I don’t have a real answer. I don’t think I’m naïve. I deeper. It’s more like magma keeping me warm instead of lava don’t think I’m expecting too much, but it’s hard not to feel shat upon by AAshooting haphazardly all over the place. It’s managed. You see, the world-at-large every step of the way. There are a couple of things that I’ve been able to channel the balled-fist, I’m hitting-walls-and-breaking- temper my anger. First off, when we were doing our math, I got another knuckles anger into something of a long-burning fuse. Oh, I’m angry, but number: sixty-four. That’s how many folks help out Razorcake in some I’m probably one of the calmest angry people you’re likely to meet. I take way, shape, or form on a regular basis. Damn, that’s awesome. Sixty- all of my “fuck yous” and edit. I take my “you’ve got to be fucking kid- four people, without whom this zine would just be a hair-brained ding me”s and take pictures and write. I seek revenge by working my ass scheme. off. Anger, coupled with belief, is a powerful motivator. The second element is a little harder to explain. Recently, I was in an What do I have to be angry about? I don’t think it’s obvious, but we do adjacent town, South Pasadena. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

Exhibition Checklist

PAPA RAGAZZE! BUCUREȘTI! LILIANA BASARAB • ALEJANDRA HERNÁNDEZ• STACY LEIGH • MOSIE ROMNEY • ED RUSCHA • JENNIFER WEST a cura di Olivia Neutron Bomb Nicodim • Bucharest July 22, 2020 – August 21, 2021 Mosie Romney, Body, Spirit 2021 DAUGHTERS OF THE OLD WORLD ORDER, HEAR US! In 1978, Ed Ruscha predicted a future with exclusively female racecar drivers. He was right. PAPA RAGAZZE is an operation of the EMPATHETIC COUNSEL, a paramilitary wing of the future MATRIARCHAL UTOPIA where men have been made obsolete and exterminated. 1700 s santa fe avenue, #160 [email protected] los angeles, california 90021 www.nicodimgallery.com In the 1970s through the early 2010s, noted “groupie” Cynthia Plaster Caster captured plaster moulds of the erect penises of famous and not-so-famous musicians. She crafted semiperfect reproductions of the manhoods of Jimi Hendrix, Jello Biafra, Frank Zappa’s bodyguard, and countless other alpha- archetypes. This was not out of subservience to the Patriarchy, but rather the first step in a decades- long process that will eliminate the necessity of any sort of manhood whatsoever. The second step starts now. This exhibition is a blueprint from your MOTHERS IN THE FUTURE for the elimination of men. We are PAPA RAGAZZE, and WE NEED YOU to enable a FUTURE WITHOUT TOXIC MEMBERS. 1700 s santa fe avenue, #160 [email protected] los angeles, california 90021 www.nicodimgallery.com Liliana Basarab Boots on the ground, 2021 Alejandra Hernández glazed ceramic, snail shells The Empress, 2021 3 pieces: each approximately -

The Love That Refuses to Speak Its Name : Examining Queerbaiting and Fan-Producer Interactions in Fan Cultures

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2015 The love that refuses to speak its name : examining queerbaiting and fan-producer interactions in fan cultures. Cassandra M. Collier, University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Collier,, Cassandra M., "The love that refuses to speak its name : examining queerbaiting and fan-producer interactions in fan cultures." (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2204. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2204 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LOVE THAT REFUSES TO SPEAK ITS NAME: EXAMINING QUEERBAITING AND FAN-PRODUCER INTERACTIONS IN FAN CULTURES By Cassandra M Collier B.A., Bowling Green State University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Women’s and Gender Studies Department of Women’s and Gender Studies University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2015 THE LOVE THAT REFUSES TO SPEAK ITS NAME: EXAMINING QUEERBAITING AND FAN-PRODUCER INTERACTIONS IN FAN CULTURES By Cassandra M Collier B.A., Bowling Green State University, 2012 A Thesis Approved on May 27, 2015 by the following Thesis Committee: ____________________________________________________ Dr, Dawn Heinecken ____________________________________________________ Dr, Diane Pecknold ____________________________________________________ Dr. -

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Meeting Josh Groban (Again): Fan/Celebrity Contact As Ordinary Behavior

Meeting Josh Groban (Again): Fan/Celebrity Contact as Ordinary Behavior Gayle Stever Empire State College, Rochester, NY [email protected] Abstract In a participant-observer ethnographic study, the researcher offers evidence from 10 years of observation of the Josh Groban fandom as an example of fans becoming friendly acquaintances of celebrities. Contrary to the way much of the psychological literature depicts fans, as celebrity worshippers or stalkers, the largest percentage of the fans observed in this study showed normal social engagement with others outside of their fan activity, and a friendly acquaintanceship with Groban that is similar to other kinds of relationships happening outside of the context of mediated relationships. Fans who pursued these relationships did so within a social context and network of other fans in most cases. Connection through music, relief from various kinds of life stressors, or the desire to participate in charity efforts are offered as some of the explanations for what motivates the fan to seek out this kind of relationship with an attractive media persona. KEYWORDS: fan, celebrity, parasocial, ethnography, audience Introduction Social relationships are defined within a culture in a myriad of ways. While more traditional relationships have been the focus of much social psychological research, little has been done to try to define the face-to-face social relationships that develop between a media celebrity and his or her fans. These relationships exist, they can be significant in the lives of both celebrities and fans, and they are a normal occurrence for a media-saturated society. IASPM@Journal vol.6 no.1 (2016) Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music ISSN 2079-3871 | DOI 10.5429/2079-3871(2016)v6i1.7en | www.iaspmjournal.net Meeting Josh Groban (Again) 105 This trend to overlook the ongoing relationships that fans have with celebrities is part of what has been referred to as the “marginalization of celebrity” (Duffett 2014: 163). -

Groupies and Other Electric Ladies Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +44 (0) 1394 389950 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/uk Groupies and Other Electric Ladies The original 1969 Rolling Stone photographs by Baron Wolman Baron Wolman ISBN 9781851497942 Publisher ACC Art Books Binding Hardback Territory World Size 300 mm x 240 mm Pages 192 Pages Illustrations 200 b&w Price £40.00 For the first time in book form, these are the photographs taken by the legendary Baron Wolman for the February 1969 'Special Super-Duper Neat Issue' of Rolling Stone Key images from a time of explosive revolution in music and culture - featuring Pamela des Barres, Catherine James, Sally Mann, Cynthia Plaster Caster and many more The original chronicle of the women who became deeply influential style icons, integral to the worlds of musicians like Frank Zappa, The Doors, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Captain Beefheart, Alice Cooper, The Who and Gram Parsons "Mr. Wolman's view of the women as style icons comes into sharp focus thanks to a new coffee-table book, Groupies and Other Electric Ladies. It collects his published portraits along with outtakes, contact sheets, the original articles from the issue and new essays that put the subjects into a modern context. The thick paper stock and oversize format emphasizes Mr. Wolman's view of the groupies as pioneers in hippie frippery." New York Times Style section "...style and fashion mattered greatly, were central to their presentation, and I became fascinated with them... I discovered what I believed was a subculture of chic and I thought it merited a story." Baron Wolman The 1960s witnessed a huge cultural revolution. -

Orienting Fandom: the Discursive Production of Sports and Speculative Media Fandom in the Internet Era

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository ORIENTING FANDOM: THE DISCURSIVE PRODUCTION OF SPORTS AND SPECULATIVE MEDIA FANDOM IN THE INTERNET ERA BY MEL STANFILL DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications with minors in Gender and Women’s Studies and Queer Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor CL Cole, Co-Chair Associate Professor Siobhan Somerville, Co-Chair Professor Cameron McCarthy Assistant Professor Anita Chan ABSTRACT This project inquires into the constitution and consequences of the changing relationship between media industry and audiences after the Internet. Because fans have traditionally been associated with an especially participatory relationship to the object of fandom, the shift to a norm of media interactivity would seem to position the fan as the new ideal consumer; thus, I examine the extent to which fans are actually rendered ideal and in what ways in order to assess emerging norms of media reception in the Internet era. Drawing on a large archive consisting of websites for sports and speculative media companies; interviews with industry workers who produce content for fans; and film, television, web series, and news representations from 1994-2009 in a form of qualitative big data research—drawing broadly on large bodies of data but with attention to depth and texture—I look critically at how two media industries, speculative media and sports, have understood and constructed a normative idea of audiencing. -

Backstage Auctions, Inc. the Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog

Backstage Auctions, Inc. The Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog Lot # Lot Title Opening $ Artist 1 Artist 2 Type of Collectible 1001 Aerosmith 1989 'Pump' Album Sleeve Proof Signed to Manager Tim Collins $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1002 Aerosmith MTV Video Music Awards Band Signed Framed Color Photo $175.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1003 Aerosmith Brad Whitford Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1004 Aerosmith Joey Kramer Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1005 Aerosmith 1993 'Living' MTV Video Music Award Moonman Award Presented to Tim Collins $4,500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1006 Aerosmith 1993 'Get A Grip' CRIA Diamond Award Issued to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1007 Aerosmith 1990 'Janie's Got A Gun' Framed Grammy Award Confirmation Presented to Collins Management $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1008 Aerosmith 1993 'Livin' On The Edge' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1009 Aerosmith 1994 'Crazy' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1010 Aerosmith -

Bebe Buell Interview

INTERVIEW HUDBA JE PRO MĚ ŽIVOT SÁM BEBE BUELL BEBEBEBE BUELL HUDBABUELL JE PRO MĚ ŽIVOT SÁM Životní příběh Bebe Buell – bývalé modelky, a přede- pozornost všude, kde se objevila. Nepatřila mezi neza- vším zpěvačky, muzikantky a umělkyně, je nejen pou- jímavé dívky, na které se zapomíná. Poznala všechny, tavý a inspirativní, ale i nesmírně bohatý z hlediska kdo na scéně něco znamenali, i ty, na které úspěch te- výčtu životních zkušeností. Není možné jej zmapovat prve čekal. V listopadu 1974 se stala první playmate v jednom rozhovoru. Bebe Buell se narodila v Ports- Playboye. Za svou kontroverzní image na obálce časo- mouthu ve Virginia Beach ve Spojených státech. Její pisu dostala výpověď z agentury. Není divu, že okouz- matka, Dorothea Johnson, je považovaná za expertku lila například Micka Jaggera, Stevena Tylera, Roda Ste- na etiketu, a založila Protokolovou školu ve Washingto- warta, Iggy Popa, Jimmyho Page, Jacka Nicholsona, nu. Její otec Harold Lloyd Buell byl vysoce oceňovaným Andyho Warhola a mnohé další. S Davidem Bowiem jí námořním důstojníkem a proslulým veteránem druhé pojilo hluboké přátelství, nikoli aféra, jak se nesmyslně světové války. Bebe však se svým otcem nevyrůstala. traduje převážně v bulvárních médiích nebo u jiných Od rodiny odešel, když jí byly pouhé dva roky. S ma- závistivců. Na jejím seznamu přátel nechybí ani uzná- minkou jsou si velmi blízké, a možná i otcův odchod vaná básnířka a zpěvačka Patti Smith nebo Debbie jejich vzájemné pouto posílil. Otcovskou lásku nelze Harry (BLONDIE). ničím nahradit a na duši člověka, který ji nepozná, zů- stane navždy šrám. Na druhou stranu je osud k Bebe V soukromém životě je Bebe Buell především matkou nesmírně štědrý a postaral se o spoustu zázraků. -

From Straight to Bizarre Zappa, Beefheart, Alice Cooper and LA's

From Straight To Bizarre Zappa, Beefheart, Alice Cooper And LA's Lunatic Fringe Sexy Intellectual DVD This considered examination of the eccentric landscape of the infamous Bizarre/Straight catalogue makes for compleling viewing and with a running time of some two hours and 40 minutes the film gives its subject the screen time it so richly deserves. Created by Zappa and Mothers manager Herb Cohen in 1968 as a release outlet specialising in the weird, the wonderful and the strictly non mainstream following Zappa's clashes with his former label MGM over the old stumblig block of artistic control the extraordinary Bizarre/Straight story is infamous for having given the world such unforgettable cultural landmarks as An Evening With Wild Man Fischer and Trout Mask Replica. With Zappa operating as LA's resident king of the freaks from his Laurel Canyon hideaway, the documentary chronicles the labels groundbreaking appetite for assembling a notorious roster of misfits including The GTOs, Wild Man Fischer, Captain Beefheart & The Magic Band, Lenny Bruce, Lord Buckley, Tim Buckley, accappella gospel group The Persuasions and the labels greatest commercial success Alice Cooper via the input of interviewees including Pamela Des Barres, Kim Fowley, Bill Harkleroad, John French, Neal Smith, Dennis Dunaway, Jeff Simmons and an impressive array of vintage performance footage. While the Bizarre/Straight era represented a unique chapter in the annals of the late 60s and early 70s the thrust of the film's critical commentary is that if the entire Bizarre/Straight operation had only given the world Trout Mask Replica it would still have more than have achieved its goal.