Labor, Masculinity, and Shifting Gender Relations In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004 Distinguished Scholars Reception Program (Date – TBD) Preface A HUNDRED YEARS OF SCHOLARSHIP AND RESEARCH AT MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS’ RECEPTION (DATE – TBD) At today’s reception we celebrate the outstanding accomplishments, excluding scholarship and creativity of Marquette remarkable records in many non-scholarly faculty, staff and alumni throughout the pursuits. It is noted that the careers of last century, and we eagerly anticipate the some alumni have been recognized more coming century. From what you read in fully over the years through various this booklet, who can imagine the scope Alumni Association awards. and importance of the work Marquette people will do during the coming hundred Given limitations, it is likely that some years? deserving individuals have been omitted and others have incomplete or incorrect In addition, this gathering honors the citations in the program listing. Apologies recipient of the Lawrence G. Haggerty are extended to anyone whose work has Faculty Award for Research Excellence, not been properly recognized; just as as well as recognizing the prestigious prize scholarship is a work always in progress, and the man for whom it is named. so is the compilation of a list like the one Presented for the first time in the year that follows. To improve the 2000, the award has come to be regarded completeness and correctness of the as a distinguishing mark of faculty listing, you are invited to submit to the excellence in research and scholarship. Graduate School the names of individuals and titles of works and honors that have This program lists much of the published been omitted or wrongly cited so that scholarship, grant awards, and major additions and changes can be made to the honors and distinctions among database. -

17 December 2003

Screen Talent Agency 818 206 0144 JUDY GELLMAN Costume Designer judithgellman.wordpress.com Costume Designers Guild, locals 892 & 873 Judy Gellman is a rarity among designers. With a Midwest background and training at the University of Wisconsin and The Fashion Institute of Technology (NYC) Judy began her career designing for the Fashion Industry before joining the Entertainment business. She’s a hands-on Designer, totally knowledgeable in pattern making, construction, color theory, as well as history and drawing. Her career has taken her from Chicago to Toronto, London, Vancouver and Los Angeles designing period, contemporary and futuristic styles for Men, Women, and even Dogs! Gellman works in collaboration with directors to instill a sense of trust between her and the actors as they create the characters together. This is just one of the many reasons they turn to Judy repeatedly. Based in Los Angeles, with USA and Canadian passports she is available to work worldwide. selected credits as costume designer production cast director/producer/company/network television AMERICAN WOMAN Alicia Silverstone, Mena Suvari (pilot, season 1) various / John Riggi, John Wells, Jinny Howe / Paramount TV PROBLEM CHILD Matthew Lillard, Erinn Hayes (pilot) Andrew Fleming / Rachel Kaplan, Liz Newman / NBC BAD JUDGE Kate Walsh, Ryan Hansen (season 1) various / Will Farrell, Adam McKay, Joanne Toll / NBC SUPER FUN NIGHT Rebel Wilson (season 1) various / Conan O’Brien, John Riggi, Steve Burgess / ABC SONS OF TUCSON Tyler Labine (pilot & series) Todd Holland, -

The Trouble We''re In: Privilege, Power, and Difference

The Trouble Were In: Privilege, Power, and Difference Allan G. Johnson Thetroublearounddifferenceisreallyaboutprivilegeandpowertheexistenceofprivilege andthelopsideddistributionofpowerthatkeepsitgoing.Thetroubleisrootedinalegacyweall inherited,andwhilewerehere,itbelongstous.Itisntourfault.Itwasntcausedbysomethingwedid ordidntdo.Butnowitsallours,itsuptoustodecidehowweregoingtodealwithitbeforewe collectivelypassitalongtothegenerationsthatwillfollowours. Talkingaboutpowerandprivilegeisnteasy,whichiswhypeoplerarelydo.Thereasonforthis omissionseemstobeagreatfearofanythingthatmightmakewhitesormalesorheterosexuals uncomfortableorpitgroupsagainsteachother,1eventhoughgroupsarealreadypittedagainstone anotherbythestructuresofprivilegethatorganizesocietyasawhole.Thefearkeepspeoplefrom lookingatwhatsgoingonandmakesitimpossibletodoanythingabouttherealitythatliesdeeper down,sothattheycanmovetowardthekindofworldthatwouldbebetterforeveryone. Difference Is Not the Problem Ignoringprivilegekeepsusinastateofunreality,bypromotingtheillusionthedifferenceby itselfistheproblem.Insomeways,ofcourse,itcanbeaproblemwhenpeopletrytoworktogether acrossculturaldividesthatsetgroupsuptothinkanddothingstheirownway.Buthumanbeingshave beenovercomingsuchdividesforthousandsofyearsasamatterofroutine.Therealillusionconnected todifferenceisthepopularassumptionthatpeoplearenaturallyafraidofwhattheydontknowor understand.Thissupposedlymakesitinevitablethatyoullfearanddistrustpeoplewhoarentlikeyou and,inspiteofyourgoodintentions,youllfinditallbutimpossibletogetalongwiththem. -

Debunking the Myth of Universal Male Privilege

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 49 2016 Debunking the Myth of Universal Male Privilege Jamie R. Abrams University of Louisville Louis D. Brandeis School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Jamie R. Abrams, Debunking the Myth of Universal Male Privilege, 49 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 303 (2016). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol49/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEBUNKING THE MYTH OF UNIVERSAL MALE PRIVILEGE Jamie R. Abrams* Existing legal responses to sexual assault and harassment in the military have stagnated or failed. Current approaches emphasize the prevalence of sexual assault and highlight the masculine nature of the military’s statistical composition and institutional culture. Current responses do not, however, incorporate masculinities theory to disentangle the experiences of men as a group from men as individuals. Rather, embedded within contestations of the masculine military culture is the un- stated assumption that the culture universally privileges or benefits the individual men that operate within it. This myth is harmful because it tethers masculinities to military efficacy, suppresses the costs of male violence to men, and positions women as perpetual outsiders. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

'The Mystery Cruise' Cast Bios Gail O'grady

‘THE MYSTERY CRUISE’ CAST BIOS GAIL O’GRADY (Alvirah Meehan) – Multiple Emmy® nominee Gail O'Grady has starred in every genre of entertainment, including feature films, television movies, miniseries and series television. Her most recent television credits include the CW series “Hellcats” as well as "Desperate Housewives" as a married woman having an affair with the teenaged son of Felicity Huffman's character. On "Boston Legal," her multi-episode arc as the sexy and beautiful Judge Gloria Weldon, James Spader's love interest and sometime nemesis, garnered much praise. Starring series roles include the Kevin Williamson/CW drama series "Hidden Palms," which starred O'Grady as Karen Miller, a woman tormented by guilt over her first husband's suicide and her son's subsequent turn to alcohol. Prior to that, she starred as Helen Pryor in the critically acclaimed NBC series "American Dreams." But O'Grady will always be remembered as the warm-hearted secretary Donna Abandando on the series "NYPD Blue," for which she received three Emmy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress in a Dramatic Series. O'Grady has made guest appearances on some of television's most acclaimed series, including "Cheers," "Designing Women," "Ally McBeal" and "China Beach." She has also appeared in numerous television movies and miniseries including Hallmark Channel's "All I Want for Christmas" and “After the Fall” and Lifetime's "While Children Sleep" and "Sex and the Single Mom," which was so highly rated that it spawned a sequel in which she also starred. Other television credits include “Major Crimes,” “Castle,” “Hawaii Five-0,” “Necessary Roughness,” “Drop Dead Diva,” “Ghost Whisperer,” “Law & Order: SVU,” “CSI: Miami,” "The Mentalist," "Vegas," "CSI," "Two and a Half Men," "Monk," "Two of Hearts," "Nothing Lasts Forever" and "Billionaire Boys Club." In the feature film arena, O'Grady has worked with some of the industry's most respected directors, including John Landis, John Hughes and Carl Reiner and has starred with several acting legends. -

The Ideology of the Long Take in the Cinema of Alfonso Cuarón by BRUCE ISAACS

4.3 Reality Effects: The Ideology of the Long Take in the Cinema of Alfonso Cuarón BY BRUCE ISAACS Between 2001 and 2013, Alfonso Cuarón, working in concert with long-time collaborator, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, produced several works that effectively modeled a signature disposition toward film style. After a period of measured success in Hollywood (A Little Princess [1995], Great Expectations [1998]), Cuarón and Lubezki returned to Mexico to produce Y Tu Mamá También (2001), a film designed as a low- budget, independent vehicle (Riley). In 2006, Cuarón directed Children of Men, a high budget studio production, and in March 2014, he won the Academy Award for Best Director for Gravity (2013), a film that garnered the praise of the American and European critical establishment while returning in excess of half a billion dollars worldwide at the box office (Gravity, Box Office Mojo). Lubezki acted as cinematographer on each of the three films.[1] In this chapter, I attempt to trace the evolution of a cinematographic style founded upon the “long take,” the sequence shot of excessive duration. Reality Effects Each of Cuarón’s three films under examination demonstrates a fixation on the capacity of the image to display greater and more complex indices of time and space, holding shots across what would be deemed uncomfortable durations in a more conventional mode of cinema. As Udden argues, Cuarón’s films are increasingly defined by this mark of the long take, “shots with durations well beyond the industry standard” (26-27). Such shots are “attention-grabbing spectacles,” displaying the virtuosity of the filmmaker over and above the requirement of narrative unfolding. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

On Anamorphic Adaptations and the Children of Men

ISSN 1751-8229 Volume Eleven, Number Two On Anamorphic Adaptations and the Children of Men Gregory Wolmart, Drexel University, United States Abstract In this article, I expand upon Slavoj Zižek’s “anamorphic” reading of Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men (2006). In this reading, Zižek distinguishes between the film’s ostensible narrative structure, the “foreground,” as he calls it, and the “background,” wherein the social and spiritual dissolution endemic to Cuaron’s dystopian England draws the viewer into a recognition of the dire conditions plaguing the post-9/11, post-Iraq invasion, neoliberal world. The foreground plots the conventional trajectory of the main character Theo from ordinary, disaffected man to self-sacrificing hero, one whose martyrdom might pave the way for a new era of regeneration. According to Zižek, in this context the foreground merely entertains, while propagating some well-worn clichés about heroic individualism as demonstrated through Hollywood’s generic conventions of an action- adventure/political thriller/science-fiction film. Zižek contends that these conventions are essential to the revelation of the film’s progressive politics, as “the fate of the individual hero is the prism through which … [one] see[s] the background even more sharply.” Zižek’s framing of Theo merely as a “prism” limits our understanding of the film by not taking into account its status as an adaptation of P.D. James’ The Children of Men (1992). This article offers such an account by interpreting the differences between the film and its literary source as one informed by the transition from Cold War to post-9/11 neoliberal conceptions of identity and politics. -

Summer 2021.Indd

Summer 2021 at | cmu.edu/osher w CONSIDER A GIFT TO OSHER To make a contribution to the Osher Annual Fund, please call the office at 412.268.7489, go through the Osher website with a credit card, or mail a check to the office. Thank you in advance for your generosity. BOARD OF DIRECTORS CURRICULUM COMMITTEE OFFICE STAFF Allan Hribar, President Stanley Winikoff (Curriculum Lyn Decker, Executive Director Jan Hawkins, Vice-President Committee Chair & SLSG) Olivia McCann, Administrator / Programs Marcia Taylor, Treasurer Gary Bates (Lecture Chair) Chelsea Prestia, Administrator / Publications Jim Reitz, Past President Les Berkowitz Kate Lehman, Administrator / General Office Ann Augustine, Secretary & John Brown Membership Chair Maureen Brown Mark Winer, Board Represtative to Flip Conti CATALOG EDITORS Executive Committee Lyn Decker (STSG) Chelsea Prestia, Editor Rosalie Barsotti Mary Duquin Jeffrey Holst Olivia McCann Anna Estop Kate Lehman Ann Isaac Marilyn Maiello Sankar Seetharama Enid Miller Raja Sooriamurthi Diane Pastorkovich CONTACT INFORMATION Jeffrey Swoger Antoinette Petrucci Osher Lifelong Learning Institute Randy Weinberg Helen-Faye Rosenblum (SLSG) Richard Wellins Carnegie Mellon University Judy Rubinstein 5000 Forbes Avenue Rochelle Steiner Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3815 Jeffrey Swoger (SLSG) Rebecca Culyba, Randy Weinberg (STSG) Associate Provost During Covid, we prefer to receive an email and University Liaison from you rather than a phone call. Please include your return address on all mail sent to the Osher office. Phone: 412.268.7489 Email: [email protected] Website: cmu.edu/osher ON THE COVER When Andrew Carnegie selected architect Henry Hornbostel to design a technical school in the late 1890s, the plan was for the layout of the buildings to form an “explorer’s ship” in search of knowledge. -

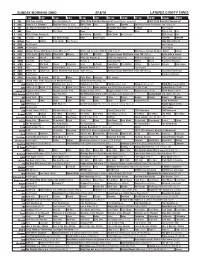

Sunday Morning Grid 3/18/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/18/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) 2018 NCAA Basketball Tournament Second Round: Teams TBA. 2018 NCAA Basketball Tournament 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Journey Journey Golf Arnold Palmer Invitational, Final Round. (N) 5 CW Los Angeles Marathon Runners compete in Los Angeles Marathon. (N) Å Marathon Post Show In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Way of Life Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program NASCAR NASCAR 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Lake City (2008) (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Retire Safe & Secure With Ed Slott (TVG) Å Rick Steves Special: European Easter Orman 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Memory Rescue With Daniel Amen, MD (TVG) Å Retire Safe & Secure 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Planeta U Calimero (TVG) Mickey Manny República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Press-Release-The-Endings.Pdf

Publication Date: September 4, 2018 Media Contact: Diane Levinson, Publicity [email protected] 212.354.8840 x248 The Endings Photographic Stories of Love, Loss, Heartbreak, and Beginning Again By Caitlin Cronenberg and Jessica Ennis • Foreword by Mary Harron 11 x 8 in, 136pp, Hardcover, Photographs throughout ISBN 978‐1‐4521‐5568‐5, $29.95 Featuring some of today’s most celebrated actresses, including Julianne Moore, Alison Pill, and Imogen Poots, the photographic vignettes in The Endings capture female characters in the throes of emotional transformation. Photographer Caitlin Cronenberg and art director Jessica Ennis created stories of heartbreak, relationship endings, and new beginnings—fictional but often inspired by real life—and set out to convey the raw emotions that are exposed in these most vulnerable states. Cronenberg and Ennis collaborated with each actress to develop a character, build the world she inhabits, and then photograph her as she lived the role before the camera. Patricia Clarkson depicts a woman meeting her younger lover in the campus library—even though they both know the relationship has been over since before it even began. Juno Temple portrays a broken‐hearted woman who engages in reckless and self‐destructive behavior to numb the sadness she feels. Keira Knightley ritualistically cleanses herself and her home after the death of her great love. Also featured are Jennifer Jason Leigh, Danielle Brooks, Tessa Thompson, Noomi Rapace, and many more. These intimate images combine the lush beauty and rich details of fashion photographs with the drama and narrative energy of film stills. Telling stories of sadness, loneliness, anger, relief, rebirth, freedom, and happiness, they are about relationship endings, but they are also about beginnings.