Dunglass Collegiate Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7. Some Lesser Lothian Streams This Is A

7. Some Lesser Lothian Streams This is a ‘wash-up’ section, in which I look briefly at a number of small streams, mostly called burns, which flow directly to the sea or the Firth of Forth, but which in terms of discharge rate are mainly an order of magnitude smaller than the rivers looked at so far. For each, I give a short account of the course and pick out a few features of interest, presenting photographs as seems appropriate. Starting furthest to the east, the streams dealt with are as follows: 1. Dunglas Burn 2. Thornton Burn 3. Spott Burn 4. Biel Water 5. East Peffer Burn 6. West Peffer Burn 7. Niddrie Burn 8. Braid Burn 9. Midhope Burn As shall become clear, some of these streams change their names more than once along their lengths and most are formed at the junction of other named streams, but hopefully any confusion will be resolved in the accounts which follow. 7.1 The Dunglas Burn The stream begins life as the Oldhamstocks Burn which collects water from a number of springs on Monynut Edge, the eastern flank of the Lammermuir Hills. No one of these feeders dominates, so the source is taken as where the name Oldhamstocks Burn appears, at grid point NT 713 699, close to the 200m contour. After flowing c3km east, the name changes to the Dunglas Burn which flows slightly north-east in a deep, steep- sided valley for just over 7km to reach the sea. For the downstream part of its course the burn is the boundary between the Lothians and the Scottish Borders, but upstream it flows in the former region. -

A Colonial Scottish Jacobite Family

A COLONIAL SCOTTISH JACOBITE FAMILY THE ESTABLISHMENT IN VIRGINIA OF A BRANCH OF THE HUM-ES of WEDDERBURN Illustrated by Letters and Other Contemporary Documents By EDGAR ERSKINE HUME M. .A... lL D .• LL. D .• Dr. P. H. Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Member of the Virginia and Kentucky Historical Societies OLD DoKINION PREss RICHMOND, VIRGINIA 1931 COPYRIGHT 1931 BY EDGAR ERSKINE HUME .. :·, , . - ~-. ~ ,: ·\~ ·--~- .... ,.~ 11,i . - .. ~ . ARMS OF HUME OF WEDDERBURN (Painted by Mr. Graham Johnston, Heraldic Artist to the Lyon Office). The arms are thus recorded in the Public ReJ?:ister of all Arms and Bearings in Scotland (Court of the Lord Lyon King of Arms) : Quarterly, first and fourth, Vert a lion rampant Argent, armed and langued Gules, for Hume; second Argent, three papingoes Vert, beaked and membered Gules, for Pepdie of Dunglass; third Argent, a cross enirrailed Azure for Sinclair of H erdmanston and Polwarth. Crest: A uni corn's head and neck couped Argent, collared with an open crown, horned and maned Or. Mottoes: Above the crest: Remember; below the shield: True to the End. Supporters: Two falcons proper. DEDICATED To MY PARENTS E. E. H., 1844-1911 AND M. S. H., 1858-1915 "My fathers that name have revered on a throne; My fathers have fallen to right it. Those fathers would scorn their degenerate son, That name should he scoffingly slight it . " -BORNS. CONTENTS PAGE Preface . 7 Arrival of Jacobite Prisoners in Virginia, 1716.......... 9 The Jacobite Rising of 1715. 10 Fate of the Captured Jacobites. 16 Trial and Conviction of Sir George Hume of Wedder- burn, Baronet . -

Ancestral Resources in the Scottish Borders

Ancestral Resources in the Scottish Borders Sources of help before you visit the Scottish Borders: Scotlandspeople is the official Scottish genealogy resource and one of the largest online sources of original genealogical information. It has more than 100 million records. You can use it via the Internet to see census records from 1841, also statutory birth, marriage and death records from 1855 and earlier Parish Records of baptisms, marriages and burials. Online you can buy credits (starting price GBP 7). For this fee, you will receive 30 "page credits" which are valid for a full year. Viewing a page of index results costs one credit and each page will contain up to 25 search results. Viewing an image costs five credits. Tip: you may want to use the online version before you travel and then put time aside during your visit to Scotland to do further research. Other genealogy resources such as www.ancestry.co.uk do not have the same reach as ScotlandsPeople but may serve to get your search underway. Specialist Genealogists Borders Ancestry offers an accredited professional genealogy research service. Specialist areas are Berwickshire, Roxburghshire and Northumberland. Major online research and a large collection of records is held on site in our well equipped research room. Personal guidance and small workshops are catered for by appointment. www.bordersancestry.co.uk Scottish Genealogy Research is a research team with over 25 years of experience. All that is required is a name, event (birth, death, or marriage) that took place in Scotland and a date; in some cases a year or decade can suffice. -

Clan Home Gathering 2018

CLAN HOME GATHERING AUGUST 2018 The Clan Home Association is pleased to announce that the next Clan Gathering will take place in Berwickshire around the weekend of 11th-12th August 2018. The dates selected mean that Clan members, family and friends, can, if they wish, join in the activities of the Coldstream Civic Week before the Gathering and go on to the Edinburgh Festival in the week following. Figure 1 - Wedderburn Castle The organisers of the Coldstream Civic Week are very excited at the prospect of many Homes, Humes and others associated with the Clan combining with them to celebrate their Civic Week. 1 Figure 2 - Duns Castle The plan is to base the Gathering at the magnificent Wedderburn Castle, as in 2013, but also, on the assumption the numbers will justify, to use the wonderful facilities at the neighbouring Duns Castle. Given that the organisers propose an even more ambitious programme than in 2013, the aim is to make use of the next fifteen months to build interest in the events so that a record number attend the 2018 Gathering. This would of course require more facilities to be available for use by attendees. Those who would like to stay at Wedderburn Castle or Duns Castle are invited to contact the Clan Association to register an interest. Rooms will be allocated on a first-come, first-served basis. At present the CHA expects Wedderburn to be rented for three nights, starting 10th August, and Duns for six nights, starting from the evening of Tuesday 7th August. 2 The Association plans are still being developed, but the current thinking is that the Gathering will start formally on Wednesday 8th August with a day given over to Genealogical matters. -

The Mineral Resources of the Lothians

The mineral resources of the Lothians Information Services Internal Report IR/04/017 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INTERNAL REPORT IR/04/017 The mineral resources of the Lothians by A.G. MacGregor Selected documents from the BGS Archives No. 11. Formerly issued as Wartime pamphlet No. 45 in 1945. The original typescript was keyed by Jan Fraser, selected, edited and produced by R.P. McIntosh. The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Scotland Mineral Resources Lothians . Bibliographical reference MacGregor, A.G. The mineral resources of the Lothians BGS INTERNAL REPORT IR/04/017 . © NERC 2004 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2004 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks. 0131-667 1000 Fax 0131-668 2683 The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the London Information Office at the Natural History Museum surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research (Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London projects. -

Cockburnspath Dunglass Dene House

License No: ES100012703 HOUSE SALES If you have a house to sell, we provide free pre-sales advice, including valuation. We will visit your home and OFFERS TO: discuss in detail all aspects of selling and buying, including costs and marketing strategy, and will explain GSB Properties’ comprehensive services. 18 HARDGATE HADDINGTON 1.While these Sales Particulars are believed to be correct, their accuracy is not warranted and they do not EAST LOTHIAN EH41 3JS form any part of any contract. All sizes are approximate. 2. Interested parties are advised to note interest through their solicitor as soon as possible in order to be kept TEL: 01620 825368 informed should a Closing Date be set. The seller will not be bound to accept the highest or any offer. FAX: 01620 824671 COCKBURNSPATH DUNGLASS DENE HOUSE OFFERS IN THE REGION OF £595,000 Location Situated on the spectacular coastline of the East Lothian/Scottish Borders boundary, some 30 minutes by car from Edinburgh. Surrounded by outstanding countryside and spectacular sea views to the east and north, Dunglass was the birthplace of James Hall, an 18th century Scottish geologist and geophysicist. One point of interest would be Dunglass Collegiate Church built c1444 which is located approximately 2km away. Quiet and peaceful, opportunities COCKBURNSPATH to pursue wide interests abound, including golf, bird watching, surfing and fishing as well as country and coastal walks along cliffs DUNGLASS or sandy beaches. The A1 Expressway allows fast, easy access to DENE HOUSE Edinburgh City Centre, Edinburgh International Airport and other main motorway networks. A bus service provides good connection OFFERS IN THE REGION OF to the City as well as nearby towns and villages. -

GRAVEYARD MONUMENTS in EAST LOTHIAN 213 T Setona 4

GRAVEYARD MONUMENT EASN SI T LOTHIAN by ANGUS GRAHAM, M.A., F.S.A., F.S.A.SCOT. INTRODUCTORY THE purpos thif eo s pape amplifo t s ri informatioe yth graveyare th n no d monuments of East Lothian that has been published by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.1 The Commissioners made their survey as long ago as 1913, and at that time their policy was to describe all pre-Reformation tombstones but, of the later material, to include only such monuments as bore heraldic device possesser so d some very notable artisti historicar co l interest thein I . r recent Inventories, however, they have included all graveyard monuments which are earlier in date than 1707, and the same principle has accordingly been followed here wit additioe latey hth an r f eighteenth-centurno y material which called par- ticularly for record, as well as some monuments inside churches when these exempli- fied types whic ordinarile har witt graveyardsyn hme i insignie Th . incorporatef ao d trades othed an , r emblems relate deceasea o dt d person's calling treatee ar , d separ- n appendixa atel n i y ; this material extends inte nineteentth o h centurye Th . description individuaf o s l monuments, whic takee har n paris parisy hb alphan hi - betical order precedee ar , reviea generae y th b df w o l resultsurveye th f so , with observations on some points of interest. To avoid typographical difficulties, all inscriptions are reproduced in capital letters irrespectiv nature scripe th th f whicf n eo i eto h the actualle yar y cut. -

JMW Overall Inner Section 2

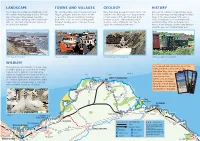

LANDSCAPE TOWNS AND VILLAGES GEOLOGY HISTORY East Lothian has a richly varied landscape, from The John Muir Way connects many towns and Many fascinating geological features can be seen Discover East Lothian’s colourful history along the coastline featuring sandy beaches, cliffs and villages, giving the visitor the chance to visit along the John Muir Way. These range from the the John Muir Way, from Musselburgh’s Roman dunes, through rolling lowland shaped by shops, cafes, harbours and historic buildings. volcanic remains of the Bass Rock and North Bridge to the ruined Dunbar castle, once a agriculture to the backdrop of the Lammermuir Most of the towns are well served by public Berwick Law, to the cliffs at Dunbar and the refuge for Mary Queen of Scots. Explore the Hills. The John Muir Way also passes by rivers, transport allowing you to return you to your sandstone arches at Bilsdean. Take time to industrial heritage of the Prestonpans area, woodland and waterfalls. start point. explore the fossil trail at Barns Ness. famous for its salt pans, and the many harbours along the Way, once thriving fishing ports. VIEW FROM CLIFF TOP TRAIL DUNBAR HARBOUR SANDSTONE ARCHES NEAR BILSDEAN PRESTONGRANGE MINING MUSEUM WILDLIFE East Lothian provides habitats for a wide range For more detailed information about the of wildlife. Coastal areas are ideal for viewing route and what can be seen on the seabirds such as gannets, terns and curlew. John Muir Way, please see Bass Rock the other leaflets that Inland, the hedgerows offer food and shelter to Fidra Craigleith cover the sections: many smaller birds. -

Download This PDF: 14022020 Register Part

East Lothian Council LIST OF APPLICATIONS DECIDED BY THE PLANNING AUTHORITY FOR PERIOD ENDING 14th February 2020 Part 1 App No 17/00954/P Officer: Stephanie McQueen Tel: 0162082 7210 Applicant Mr & Mrs I McNeill Applicant’s Address 24 Winton Place Tranent East Lothian EH33 1AE Agent Slorach Wood Architects Agent’s Address Per Kirsty Watson Station Masters Office Station Road South Queensferry EH30 9JP Proposal Formation of a eco accommodation site with a shop (Class 1 Use), coffee shop (Class 3 Use), 5 holiday cabins, 1 house and associated works Location Land Adjacent To Roselea Cottage Pencaitland East Lothian EH34 5DH Date Decided 12th February 2020 Decision Granted Permission Council Ward Haddington And Lammermuir Community Council Pencaitland Community Council App No 18/01362/P Officer: Ciaran Kiely Tel: 0162082 7995 Applicant Dunglass Ltd Applicant’s Address Per Mr Peter Humphrey Spott Road Dunbar East Lothian EH42 1LE Agent Agent’s Address Proposal Renewal of planning permission 14/0664/P - Alteration and extension to laboratory buildings to form 7 houses, erection of garages, change of use of laboratory and agricultural land to form domestic garden ground and common amenity space, formation of vehicular access and associated works Location Gin Head Tantallon North Berwick East Lothian Date Decided 10th February 2020 Decision Granted Permission Council Ward North Berwick Coastal Community Council North Berwick Community Council App No 19/01031/P Officer: Neil Millar Tel: 0162082 7383 Applicant Mr Tony Murphy Applicant’s Address -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Appreciations 1 Article Titles 1 Book Reviews 3 Contributors 4 Family Trees 5 General Index 9 Illustrations 6 Queries 5 Recent Additions to the Library 5 INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) LX.iv.177 A very short visit to Scotslot LIX.iii.144 Agnes de Graham, wife of John de Monfode, and Sir John Douglas LXI.iv.129 An Octogenarian Printer’s Recollections LX.iii.108 Ancestors at Bannockburn LXI.ii.39 Andrew Robertson of Gladsmuir LIX.iv.159: LX.i.31 Anglo-Scottish Family History Society LIX.i.36 Antiquarian is an odd name for a society LIX.i.27 Balfours of Balbirnie and Whittinghame LX.ii.84 Battle of Bannockburn Family History Project LXI.ii.47 Bothwells’ Coat-of-Arms at Glencorse Old Kirk LX.iv.156 Bridges of Bishopmill, Elgin LX.i.26 Cadder Pit Disaster LX.ii.69 Can you identify this wedding party? LIX.iii.148 Candlemakers of Edinburgh LIX.iii.139 Captain Ronald Cameron, a Dungallon in Morven & N. -

Dunglass Wedding Venue Bro 2020 V2

Unforgeabl Occasions wedding packages WELCOME TO DUNGLASS ESTATE Eas Loia As you drive through the stone gates, up a winding driveway lined with ancient trees, you are greeted by one of the most stunning views in all of East Lothian. With acres of landscaped grounds and a beautiful 15th Century Gothic church as well as guest accommodation and a secluded, elevated honeymoon suite, the possibilities are endless for the design of your wedding day. 2020 is a particularly exciting time for our couples at Dunglass, as the long anticipated conversion of our historic Stables buildings into a beautiful new ceremony space will be completed, giving additional options for the most special of days regardless of the number of guests. The estate, run by ourselves, Joyce and Simon Usher, is nestled between East Lothian and the Scottish Borders. Our experienced team at Dunglass prides itself on working closely with you to create your unique day in a truly unrivalled location. We also oer the most delicious food options delivered by three highly talented catering partners, who are dedicated to delivering exceptional events at Dunglass. Your only challenge will be to decide which one to choose! To understand what we can oer, we will be delighted to show you around and discuss the potential for a truly memorable occasion. Our sales manager will contact you to arrange an early date, where we can discuss your wedding in detail and show what we can do for you. W loo forward to meeting yo! Joyce and Simon Usher Spcious, Intimat, Mgnificen, welcoming elegan & goi & tylis ccommodating & histori SEA VIEW HOUSE THE PAVILION DUNGLASS CHURCH THE THE TOTAL WEDDING DUNGLASS VENUE PACKAGE PAVILION PACKAGE Monday - Thursday With excellent road and rail links, We are delighted to showcase our bespoke built Dunglass is perfectly placed for local Dunglass Pavilion. -

Annex 3 – Peter Mcgowan Associates, “Borders Designed Landscapes Survey: Schedule of Identified Sites”

Annex 3 – Peter McGowan Associates, “Borders Designed Landscapes Survey: Schedule of Identified Sites” Annex 3: Detailed Survey Reference Site name County Parish Grid reference 1 Baddinsgill Peebles Linton [West] NT 132 549 Notable Characteristics Forms landscape of upper glen of Lyne Water and is very prominent in approach Extensive and varied woods and belts Community woodland Site Description Settlement of Badonsgill is recorded on Blaeu (1654), and of Barronsgill on Roy (c.1750), the latter with a scatter of cultivation riggs around it, and a single, walled and tree-lined enclosure to S. Further planting, seen on OS (1850s), is augmented, possibly around the time of the redevelopment of the house as a shooting lodge in 1890s. A remotely located site at the S of Pentland Hills at top of Lyne Water and end of a no-through road from West Linton, lying below Baddingsgill reservoir. Complex and extensive layout of small woods and broad belts reaching along the valley seen from a distance along the approach. Mature MB with SP and MC in core with MC or conifer monoculture in outer plantations. Community wood with a one- mile walk in core. High impact in locality but not visible further afield. Significance Local, Outstanding 31 August 2009 Page 1 of 195 Reference Site name County Parish Grid reference 2 Lynedale / Medwyn Peebles West Linton NT 141 525 Notable Characteristics Wooded valleys sides providing setting for 19thC houses and newer development Site Description No clear evidence of a substantial house or plantations prior to the building of Lynedale House in the early 19thC, although NSA (1830s) described the felling of a considerable deal of valuable timber about the yards and steadings in the parish about a century before.