Tradition and Change in Methodism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baptism: Valid and Invalid

BAPTISM: VALID AND INVALID The following information has been provided to the Office of Worship and Christian Initiation by Father Jerry Plotkowski, Judicial Vicar. It is our hope that it will help you in discerning the canonical status of your candidates. BAPTISM IN PROTESTANT RELIGIONS Most Protestant baptisms are recognized as valid baptisms. Some are not. It is very difficult to question the validity of a baptism because of an intention either on the part of the minister or on the part of the one being baptized. ADVENTISTS: Water baptism is by immersion with the Trinitarian formula. Valid. Baptism is given at the age of reason. A dedication ceremony is given to infants. The two ceremonies are separate. (Many Protestant religions have the dedication ceremony or other ceremony, which is not a baptism. If the church has the dedication ceremony, baptism is generally not conferred until the age of reason or until the approximate age of 13). AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL: Baptism with water by sprinkling, pouring, or dunking. Trinitarian form is used. Valid. There is an open door ceremony, which is not baptism. AMISH: This is coupled with Mennonites. No infant baptism. The rite of baptism seems valid. ANGLICAN: Valid baptism. APOSTOLIC CHURCH: An affirmative decision has been granted in one case involving "baptism" in the apostolic church. The minister baptized according to the second chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, and not St. Matthew. The form used was: "We baptize you into the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of sins, and you shall receive a gift of the Holy Ghost." No Trinitarian form was used. -

John Wesley's Teaching Concerning Perfection Edward W

JOHN WESLEY'S TEACHING CONCERNING PERFECTION EDWARD W. H. VICK Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan Wesley has often been characterized as Arminian rather than as Calvinistic. The fact that he continuously called for repentance from sin, published a journal called the Arminian Magazine, was severe in his strictures against predestination and unconditional election, engaged in controversial cor- respondence with Whitefield over the matter of election, perfection and perseverance seem to indicate a great gulf between his teaching and that of Calvin. Gulf there may be, but it need not be made to appear wider at certain points than can justly be claimed. The fact is that exclusive attention to his opposition to predestination may lead to neglect of his teaching on the relationship between faith and grace. This is not to deny that Wesley was opposed to important Calvinistic tenets. In his sermon on Free Grace, delivered in 1740, he states why he is opposed to the doctrine of pre- destination : (I) it makes preaching vain, needless for the elect and useless for the non-elect ; (2) it takes away motives for following after holiness ; (3) it tends to increase sharpness of temper and contempt for those considered to be outsiders ; (4) it tends to destroy the comfort of religion ; (5) it destroys zeal for good works ; (6) it makes the whole Christian revelation unnecessary and (7) self-contradictory ; (8) it represents the Lord as saying one thing and meaning J. Wesley, Sermons on Several Occasions, I (New York, 1827)~ 13-19. 202 EDWARD W. H. VICK another: God becomes more cruel and unjust than the devil. -

Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism

Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Edwards, Graham M. Citation Edwards, G. M. (2018). Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 28/09/2021 05:58:45 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/621795 Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Chester for the degree of Doctor of Professional Studies in Practical Theology By Graham Michael Edwards May 2018 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work is my own, but I am indebted to the encouragement, wisdom and support of others, especially: The Methodist Church of Great Britain who contributed funding towards my research. The members of my group interviews for generously giving their time and energy to engage in conversation about the life of their churches. My supervisors, Professor Elaine Graham and Dr Dawn Llewellyn, for their endless patience, advice and support. The community of the Dprof programme, who challenged, critiqued, and questioned me along the way. Most of all, my family and friends, Sue, Helen, Simon, and Richard who listened to me over the years, read my work, and encouraged me to complete it. Thank you. 2 CONTENTS Abstract 5 Summary of Portfolio 6 Chapter One. Introduction: Methodism, a New Narrative? 7 1.1 Experiencing Methodism 7 1.2 Narrative and Identity 10 1.3 A Local Focus 16 1.4 Overview of Thesis 17 Chapter Two. -

The Great Awakening and Other Revivals in the Religious Life of Connecticut

TERCENTENARY COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT COMMITTEE ON HISTORICAL PUBLICATIONS The Great Awakening and Other Revivals in the Religious Life of Connecticut (DOUBLE NUMBER) XXV/ PUBLISHED FOR THE TERCENTENARY COMMISSION BY THE YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS *934 CONNECTICUT STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION LIBRARY SERVICE CENTER MIDDLETOWN, CONNECTION . TERCENTENARY COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT COMMITTEE ON HISTORICAL PUBLICATIONS The Great Awakening and Other Revivals in the Religious Life of Connecticut MARY HEWITT MITCHELL I HE Puritan founders of Connecticut, like those of Massachusetts, were the offspring of a remarkable revival of religious fervor in England. They moved across the Atlantic to Tset up their religious Utopia in the New World. Spiritual exaltation and earnestness sustained them amid the perils and pains of establishing homes and churches in the New England wilderness. Clergymen were their leaders. On the Sabbath, the minister, in gown and bands, preached to his flock beneath a tree or under some rude shelter. On other days, in more practical attire, he guided and shared the varied labors incident to the foundation of the new settlement. The younger generation and the later comers, however, had more worldliness mingled with their aims, but re- ligion continued a dominant factor in the expanding colonial life. Perhaps the common man felt personal enthusiasm for religion less than he did necessary regard for provisions of the law, yet as he wandered into un- occupied parts of the colony, he was not leaving the watch and ward of the church. Usually, indeed, he did not wish to, since even the most worldly-minded desired the honors and privileges attached to membership in the church-state. -

The Ministry of Deacons in Methodism from Wesley to Today Kenneth E

QUARTERLY REVIEW/WINTER 1999 S7.00 The Ministry of Deacons in Methodism from Wesley to Today Kenneth E. Roioe Diakonia as a "Sacred Order" in The United Methodist Church Diedra Kriewald Deacons as Emissary-Servants: A Liturgical Tlieology Benjamin L. Hartley Editorial Board Ted A. Campbell Roger W. Ireson, Chair Wesley Theological General Board of Higher Seminary Education and Ministry The United Methodist Church Jimmy Carr General Board of Higher Education Jack A. Keller, Jr. and Ministry The United Methodist The United Methodist Church Publishing House Rebecca Chopp Thomas W, Oglctree Candler School of The Divinity School Theology Yale University Emory University Harriett Jane Olson Duane A. Ewers The United Methodist General Board of Higher Publishing House Education and Ministry The United Methodist Church Russell E. Richey Duke Divinity School Patricia Farris First United Methodist Church Marjorie Hewitt Suchocki Santa Monica, CA Claremont School of Theology Grant Hagiya Linda E. Thomas Centenary United Garrett-Evangelical Methodist Church Theological Seminary Los Angeles, CA Traci West John E. Hamish The Theological School General Board of Higher Drew University Education and Ministry The United Methodist Church Hendrik R. Pieterse, Editor Sylvia Street, Production Manager Tracey Evans, Production Coordinator Quarterly Review A Journal of Theological Resources for Ministry Volume 19, Number 4 QR A Publication of The United Methodist Publishing House and the United Methodist Board of Higher Education and Ministry Quarterly Review (ISSN 0270-9287) provides continuing education resources for scholars. Christian educators, and lay and professional ministers in The United Methodist Church and other churches. QR intends to be a forum in which theological issues of significance to Christian ministry can be raised and debated. -

Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry

This electronic file is made available to churches and interested parties as a means of encouraging individual and ecumenical discussion of the text. For extended use we encourage you to purchase the published printed text, available from WCC Publications. (In case of any discrepancies the published printed text should be considered authoritative.) BAPTISM, EUCHARIST AND MINISTRY FAITH AND ORDER PAPER NO. 111 WORLD COUNCIL OF CHURCHES, GENEVA, 1982 © Copyright 1982 World Council of Churches, 150 route de Ferney, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE................................................................................................................................. v BAPTISM I. THE INSTITUTION OF BAPTISM ............................................................................ 1 II. THE MEANING OF BAPTISM ................................................................................... 1 A. Participation in Christ’s Death and Resurrection.................................................... 1 B. Conversion, Pardoning and Cleansing .................................................................... 1 C. The Gift of the Spirit ............................................................................................... 2 D. Incorporation into the Body of Christ ..................................................................... 2 E. The Sign of the Kingdom ........................................................................................ 2 III. BAPTISM AND FAITH................................................................................................ -

Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pentecostal/Charismatic Movements Page 1 Pentecostal Movement The first two hundred years (100-300 AD) The emphasis on the spiritual gifts was evident in the false movements of Gnosticism and in Montanism. The result of this false emphasis caused the Church to react critically against any who would seek to use the gifts. These groups emphasized the gift of prophecy, however, there is no documentation of any speaking in tongues. Montanus said that “after me there would be no more prophecy, but rather the end of the world” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol II, p. 418). Since his prophecy was not fulfilled, it is obvious that he was a false prophet (Deut . 18:20-22). Because of his stress on new revelations delivered through the medium of unknown utterances or tongues, he said that he was the Comforter, the title of the Holy Spirit (Eusebius, V, XIV). -

Reflections on Assurance

WTJ 54 (1992) 1-29 REFLECTIONS ON CHRISTIAN ASSURANCE* D. A. CARSON I. Introduction O far as I know, there has been no English-language, full-scale treat- Sment of the biblical theology of Christian assurance for more than fifty years. There have been numerous dictionary articles and the like, along with occasional discussions in journals. There have also been sophisticated studies of assurance as found in the theology of some notable Christian thinker or period, such as the book by Yates that examines assurance with special reference to John Wesley, 1 or the discussion of assurance that per- vades Kendall's treatment of the move from Calvin to English Calvinism, 2 or the dissertation by Beeke that studies personal assurance from Westmin- ster to Alexander Comrie. 3 There have been countless studies of related biblical themes: perseverance, apostasy, the nature of covenant, the nature of faith, justification, and much more—too many to itemize; and there have been numerous popular treatments of Christian assurance. But although at one time assurance was not only a question of pressing pastoral importance but in certain respects a test of theological systems, in recent decades it has not received the attention it deserves. This paper makes no pretensions of redressing the balance. My aim is far more modest. First, I shall identify a number of tendencies in contemporary literature that bear on Christian assurance. Then I shall offer a number of biblical and theological reflections—really not much more than pump- priming—designed to set out the contours in which a biblical theology of Christian assurance might be constructed. -

Arminianism and Adventism: Assurance of Salvation

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Memory, Meaning & Life Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary 10-16-2010 Arminianism and Adventism: Assurance of Salvation David Hamstra Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/mml Recommended Citation Hamstra, David, "Arminianism and Adventism: Assurance of Salvation" (2010). Memory, Meaning & Life. 60. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/mml/60 This Blog Post is brought to you for free and open access by the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Memory, Meaning & Life by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wayback Machine - http://web.archive.org/web/20120716005955/http://www.memorymeaningfaith.org/blog/2010/… Memory, Meaning & Faith Main About Archives October 16, 2010 Arminianism and Adventism: Assurance of Salvation Keith also brought an Arminius tee-shirt to the conference, but decided not to wear it for similar reasons to Dr. Olson. He's stopped wearing it generally because he got tired of people coming up to him asking him why he was wearing a Shakespeare tee-shirt. Keith Stanglin remarked that his paper, "Assurance of Salvation: An Arminian Account," is still a bit rough as he only recently found out about the conference. So, he said with tongue in cheek, we'll just have to trust him that he's not making this up, since it's still missing many footnotes. Arminius view on assurance is important for thee reasons. 1. Historical - It illuminates the shape of his debate. -

Justification, Sanctification, Good Works and Assurance Presents

presents... Justification, Sanctification, Good Works and Assurance “Aslan,” said Lucy, “you’re bigger.” “That is because you are older, little one,” answered he. “Not because you are?” “I am not. But every year you grow, you will find me bigger.” Marcus Honeysett was C.S. Lewis, Prince Caspian London Team Leader for UCCF before founding Living Leadership, which serves churches around the UK in growing disciple-making What a profound picture of sanctification this is. As the leaders. He has authored or co- understanding of the faith-filled Lucy grows and her authored four books and many articles. He is married to Ros relationship with Aslan deepens, so he gets bigger and bigger. and they are members of Crofton As she grows – if she grows, when she grows – he is magnified Baptist Church. in her eyes. @marcushoneysett L The purpose of the Christian life – indeed of life – is the magnification of the greatness of God and his glory, most especially in the glory of his Son and the gospel of his grace. The purpose of justification is nothing less than union with Christ. Created in him, crucified with him, united with him in his resurrection, justified, sanctified, made alive in him and seated with him in glory. The Christian life is, literally, Jesus everything. To live is Christ. To live is to have Christ formed in us. Not only to be justified, but to become Christlike. As we grow, he is magnified. How could it be otherwise, seeing as the point of creation itself is that he might be supremely preeminent? (Col 1:18) No wonder Paul was wracked with anguish when the Galatians seemed to be allowing Christ’s formation in them, and them in him, to slip away: Gal 4:19 …I am again in the pains of childbirth until Christ is formed in you… Christ in us, but not us in him? Some time ago I found myself in conversation with an evangelist. -

What Is Classical Arminianism?

SEEDBED SHORTS Kingdom Treasure for Your Reading Pleasure Copyright 2014 by Roger E. Olson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission, except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles. uPDF ISBN: 978-1-62824-162-4 3 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Roger E. Olson Roger Olson is a Christian theologian of the evangelical Baptist persuasion, a proud Arminian, and influenced by Pietism. Since 1999 he has been the Foy Valentine Professor of Christian Theology of Ethics at George W. Truett Theological Seminary of Baylor University. Before joining the Baylor community he taught at Bethel College (now Bethel University) in St. Paul, Minnesota. He graduated from Rice University (PhD in Religious Studies) and North American Baptist Seminary (now Sioux Falls Seminary). During the mid-1990s he served as editor of Christian Scholar’s Review and has been a contributing editor of Christianity Today for several years. His articles have appeared in those publications as well as in Christian Century, Theology Today, Dialog, Scottish Journal of Theology, and many other religious and theological periodicals. Among his published works are: 20th Century Theology (co-authored with the late Stanley J. Grenz), The Story of Christian Theology, The Westminster Handbook to Evangelical Theology, Arminian Theology, Reformed and Always Reforming, and Against Calvinism. He enjoys -

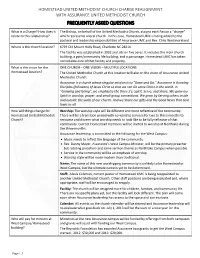

Frequently Asked Questions

HOMESTEAD UNITED METHODIST CHURCH CHARGE REALIGNMENT WITH ASSURANCE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS What is a Charge? How does it The Bishop, on behalf of the United Methodist Church, assigns each Pastor a “charge” relate to this relationship? which represents a local church. In this case, Homestead UMC is being added to the pastoral and leadership responsibilities of Assurance UMC and Rev. Chris Westmoreland. Where is the church location? 6729 Old Mount Holly Road, Charlotte NC 28214 The facility was established in 1932 and sits on five acres. It includes the main church building, a gym/community life building, and a parsonage. Homestead UMC has taken remarkable care of that facility and property. What is the vision for the ONE CHURCH – ONE VISION – MULTIPLE LOCATIONS Homestead location? The United Methodist Church at this location will take on the vision of Assurance United Methodist Church: Assurance is a church whose singular mission is to “Grow and Go.” Assurance is Growing Disciples (followers) of Jesus Christ so that we can Go serve Christ in the world. In “Growing and Going”, we emphasize the three S’s: Spirit, Serve, and Share. We grow our Spirit in worship, prayer, and small group connections. We grow by Serving others inside and outside the walls of our church. And we Share our gifts and the Good News that God loves us all. How will things change for Worship: The worship style will be different and more reflective of the community. Homestead United Methodist There will be a transition period with no worship services for two to three months to Church? renovate and discern what worship needs to look like to be fully reflexive of that community.