The Impact of Thatcherism on Representations of Work And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auf Wiedersehen Pet: Past and Present

H-Film Auf Wiedersehen Pet: Past and Present Discussion published by Elif Sendur on Wednesday, November 13, 2019 We are inviting abstracts for a publication on the British television series Auf Wiedersehen Pet to mark the 35th anniversary of its first screening. We are interested in a range of contributions including; academic articles, fan responses, reminiscences, revisiting locations, interviews, etc. Auf Wiedersehen Pet first appeared on the television screens in 1983. Initially conceived as a single six part series it went on to run for 40 episodes over 5 series. The first series followed the plight of British workers forced to look for work overseas as recession hit Britain. The series, in 1986 showed a brighter, affluent Britain, but one which was ultimately corrupt. Voted in a recent Radio Times poll the number one favourite ITV drama over its 50 year history,Auf Wiedersehen, Pet continues to capture the imagination of the viewing public since its first airing in 1983. Over four series and a special, it portrayed the highs and lows of a disparate band of labourers. AufPet, as it became known to the writers, had a prestigious lineage. The series was the brainchild of a northern film-maker, Franc Roddam. It arrived after a long line of impressive cinema films and TV dramas which represented gritty working class life in all its glory and horrors. Such hard-hitting ‘social problem’ dramas as Cathy Come Home, Peter Terson’s The Fishing Party (BBC Play for Today, 1972), Boys From the Black Stuff and Roddam’s own The Family, had already begun to pinpoint the central dramatic component parts of working class representation; jobs (getting them, losing them, suffering over them), damaged relationships, drink, sex and music. -

A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott

David Richard Hexter Thesis Title: A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 1 Statement of Originality I, David Richard Hexter, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged and my contribution indicated. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the college has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. David R Hexter 12/01/2016 2 Abstract Author: David Hexter, PhD candidate Title of thesis: A Critical Assessment of the Political Doctrines of Michael Oakeshott Description The thesis consists of an Introduction, four Chapters and a Conclusion. In the Introduction some of the interpretations that have been offered of Oakeshott’s political writings are discussed. The key issue of interpretation is whether Oakeshott is best considered as a disinterested philosopher, as he claimed, or as promoting an ideology or doctrine, albeit elliptically. -

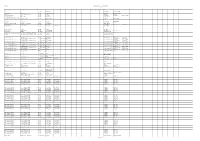

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Made on Merseyside

Made on Merseyside Feature Films: 2010’s: Across the Universe (2006) Little Joe (2019) Beyond Friendship Ip Man 4 (2018) Yesterday (2018) (2005) Tolkien (2017) X (2005) Triple Word Score (2017) Dead Man’s Cards Pulang (2016) (2005) Fated (2004) Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool (2016) Alfie (2003) Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them Digital (2003) (2015) Millions (2003) Florence Foster Jenkins (2015) The Virgin of Liverpool Genius (2014) (2002) The Boy with a Thorn in His Side (2014) Shooters (2001) Big Society the Musical (2014) Boomtown (2001) 71 (2013) Revenger’s Tragedy Christina Noble (2013) (2001) Fast and Furious 6 John Lennon-In His Life (2012) (2000) Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit Parole Officer (2000) (2012) The 51st State (2000) Blood (2012) My Kingdom Kelly and Victor (2011) (2000) Captain America: The First Avenger Al’s Lads (2010) (2000) Liam (2000) 2000’s: Route Irish (2009) Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2009) Nowhere Fast (2009) Powder (2009) Nowhere Boy (2009) Sherlock Holmes (2008) Salvage (2008) Kicks (2008) Of Time in the City (2008) Act of Grace (2008) Charlie Noads RIP (2007) The Pool (2007) Three and Out (2007) Awaydays (2007) Mr. Bhatti on Holiday (2007) Outlaws (2007) Grow Your Own (2006) Under the Mud (2006) Sparkle (2006) Appuntamento a Liverpool (1987) No Surrender (1986) Letter to Brezhnev (1985) Dreamchild (1985) Yentl (1983) Champion (1983) Chariots of Fire (1981) 1990’s: 1970’s: Goin’ Off Big Time (1999) Yank (1979) Dockers (1999) Gumshoe (1971) Heart (1998) Life for a Life (1998) 1960’s: Everyone -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

2AQ~L~ Lawrence.N

fIICTN COMt~W$~bM IWIS ISDI EFJSIKNOF U 2AQ~L~ Lawrence.N. Noble, Ea uiro W?ashamingoD.206 Larec Nr.Noble, sur cashingtonreDsC. 20463 n h leto f hc a~a n the defeat of Senator Frank R. Lautenberg in the 1994 United States Senate election in New Jersey in violation of 2 U.S.C. 5441(b) and 5441(d) Almost every day, Monday through Friday, for four hours a day, 3:00 P.M. to 7:00 P.M. WABC put a paid employee, Bob Grant, on the air who uses the four hours block of time to expressly ad- vocate the election of Chuck Haytaian and the defeat of Frank R. Lautenberg. As you are aware, corporate media have been given a efat exception from 2 U.S.C. §441(b), nL.n. to permit an intermit- tent "editorial" advocating the election of a candidate. Tradi- tionally, that exception has been narrowly construed. WABC has made a decision at the highest levels of corporate policy to allow that "exception" to gobble up the prohibition. By committing four hours of air time during "prime time", 5 days a week, WABC has illegally contributed and subsidized a Federal election in violation of Federal law, expending hundreds of thousands of dollars expressly advocating the election of Chuck Haytaian and the defeat of Frank R. Lautenberg. WABO is believed to be a wholly owned corporation asset of Capi- tal Cities, Inc. which is owned by the American Broadcasting Corp. with offices at 2 Penn Plaza, 17th Floor, New York, NY 10121. -

Yes Minister & Yes Prime Minister

FREE YES MINISTER & YES PRIME MINISTER - THE COMPLETE AUDIO COLLECTION: THE CLASSIC BBC COMEDY SERIES PDF Antony Jay,Jonathan Lynn,Paul Eddington,Sir Nigel Hawthorne,Full Cast | 1 pages | 14 Dec 2016 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781910281215 | English | London, United Kingdom Yes Minister - Wikipedia Audible Premium Plus. Cancel anytime. Through the ages of Britain, from the 15th century to the 21st, Edmund Blackadder has meddled his way along the bloodlines, aided by his servant and sidekick, Baldrick, and hindered by an assortment of dimwitted aristocrats. By: Ben Eltonand others. A rollicking collection of six acclaimed dramatisations of P. By: P. Set in the Machiavellian world of modern PR, Absolute Power introduces us to London-based 'government-media relations consultancy' Prentiss McCabe, whose partners Charles Prentiss and Martin McCabe are frequently embroiled in the machinations of the British political system. By: Mark Tavener. It is Tom Good's 40th birthday, and he feels thoroughly unfulfilled. If only he can discover what 'It' is, and if he can, will his wife Barbara agree to do 'It' with him? By: John Esmondeand others. Welcome to Fawlty Towers, where attentive hotelier Basil Fawlty and his charming wife Sybil will attend to your every need - in your worst nightmare. With hapless waiter Manuel and long-suffering waitress Polly on hand to help, anything could happen during your stay - and probably will. By: John Cleeseand others. By: Oscar Wilde. Three series were broadcast between andwith episodes adapted from their TV counterparts by Harold Snoad and Michael Knowles. By: David Croftand others. In the BBC adapted its hit wartime TV series for radio, featuring the original television cast and characters. -

John Simm ~ 47 Screen Credits and More

John Simm ~ 47 Screen Credits and more The eldest of three children, actor and musician John Ronald Simm was born on 10 July 1970 in Leeds, West Yorkshire and grew up in Nelson, Lancashire. He attended Edge End High School, Nelson followed by Blackpool Drama College at 16 and The Drama Centre, London at 19. He lives in North London with his wife, actress Kate Magowan and their children Ryan, born on 13 August 2001 and Molly, born on 9 February 2007. Simm won the Best Actor award at the Valencia Film Festival for his film debut in Boston Kickout (1995) and has been twice BAFTA nominated (to date) for Life On Mars (2006) and Exile (2011). He supports Man U, is "a Beatles nut" and owns seven guitars. John Simm quotes I think I can be closed in. I can close this outer shell, cut myself off and be quite cold. I can cut other people off if I need to. I don't think I'm angry, though. Maybe my wife would disagree. I love Manchester. I always have, ever since I was a kid, and I go back as much as I can. Manchester's my spiritual home. I've been in London for 22 years now but Manchester's the only other place ... in the country that I could live. You never undertake a project because you think other people will like it - because that way lies madness - but rather because you believe in it. Twitter has restored my faith in humanity. I thought I'd hate it, but while there are lots of knobheads, there are even more lovely people. -

Find Doc < Fast Living: Remembering the Real Gary Holton

HYJUSYU6P3BU # eBook \ Fast Living: Remembering the Real Gary Holton Fast Living: Remembering the Real Gary Holton Filesize: 2.36 MB Reviews This book is wonderful. it absolutely was writtern very completely and valuable. Your lifestyle period will be enhance once you full reading this article pdf. (Alivia Hartmann) DISCLAIMER | DMCA IJ20J9BUDBI1 \ eBook « Fast Living: Remembering the Real Gary Holton FAST LIVING: REMEMBERING THE REAL GARY HOLTON New Haven Publishing Ltd, United Kingdom, 2013. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 229 x 152 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. Be proud of everything that you do, or have a fucking damn good reason for doing something which you re not proud of. (Gary Holton to Danny Baker, NME, November 1984, a year before his death) A true rock n roll casualty, Gary Holton packed a lot into his thirty- three years, including fronting proto-punk legends, Heavy Metal Kids, and playing a leading role in one of the most revered TV dramas of its day. Drawing on her own recollections and first-hand accounts of others who knew him, Teddie Dahlin completes the picture of a man who never outran his demons but who, in the process, gave a lot of pleasure and some little anguish to those who surrounded him. Born in East End London, Holton became a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company at an early age before joining a touring production of Hair, prior to pursuing long-harboured musical ambitions. While Heavy Metal Kids never did reach the heights predicted for them, there was a number one solo single in Europe and an invitation to front AC/DC that was declined. -

The Acid House a Film by Paul Mcguigan

100% PURE UNCUT IRVINE WELSH The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan a Zeitgeist Films release The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan based on the short stories from “The Acid House” by Irvine Welsh Starring Ewen Bremner Kevin McKidd Maurice Roëves Martin Clunes Jemma Redgrave Introducing Stephen McCole Michelle Gomez Arlene Cockburn Gary McCormack Directed by Paul McGuigan Screenplay by Irvine Welsh Director of Photography Alasdair Walker Editor Andrew Hulme Costume Designers Pam Tait & Lynn Aitken Production Designers Richard Bridgland & Mike Gunn Associate Producer Carolynne Sinclair Kidd Produced by David Muir & Alex Usborne FilmFour presents a Picture Palace North / Umbrella Production produced in association with the Scottish Arts Council National Lottery Fund, the Glasgow Film Fund and the Yorkshire Media Production Agency UK • 1999 • 112 mins • Color • 35mm In English with English subtitles Dolby Surround Sound a Zeitgeist Films release The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan Paul McGuigan’s THE ACID HOUSE is a surreal triptych adapted by Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh from his collection of short stories. Combining a vicious sense of humor with hard- talking drama, the film reaches into the hearts and minds of the chemical generation, casting a dark and unholy light into the hidden corners of the human psyche. Part One The Granton Star Cause The first film of the trilogy is a black comedy of revenge, soccer and religion that come together in one explosive story. Boab Coyle (STEPHEN McCOLE) thinks he has it all, a ‘tidy’ bird, a job, a cushy number living at home with his parents and a place on the kick-about soccer team the Granton Star. -

Oxford DNB: January 2020

Oxford DNB: January 2020 Welcome to the fifty-ninth update of the Oxford DNB, which adds biographies of 228 individuals who died in the year 2016 (it also includes three subjects who died before 2016, and who have been included with new entries). Of these, the earliest born is the author E.R. Braithwaite (1912-2016) and the latest born is the geriatrician and campaigner for compassionate care in health services, Kate Granger (1981- 2016). Braithwaite is one of nine centenarians included in this update, and Granger one of sixteen new subjects born after the Second World War. The vast majority (165, or 72%) were born in the 1920s and 1930s. Fifty-one of the new subjects who died in 2016 (or just under 23% of the cohort) are women. From January 2020, the Oxford DNB offers biographies of 63,693 men and women who have shaped the British past, contained in 61,411 articles. 11,773 biographies include a portrait image of the subject—researched in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery, London. As ever, we have a free selection of these new entries, together with a full list of the new biographies. The complete dictionary is available, free, in most public libraries in the UK. Libraries offer 'remote access' that enables you to log in at any time at home (or anywhere you have internet access). Elsewhere the Oxford DNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Full details of participating British public libraries, and how to gain access to the complete dictionary, are available here. -

THE TENTH DOCTOR ADVENTURESVOLUME THREE We Make Great Full-Cast Audio Dramas and Audiobooks That Are Available to Buy on CD And/Or Download

ISSUE: 122 • APRIL 2019 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM DARK SHADOWS BLOODLINE WE RETURN TO THE TOWN OF COLLINSPORT! UNIT: THE NEW SERIES INCURSIONS A RIVER RUNS THROUGH THE NEW UNIT BOX SET! DOCTOR WHO NEW VOICES THE BRIGADIER AND LIZ SHAW RETURN! WIBBLY WOBBLY THE TENTH DOCTOR ADVENTURESVOLUME THREE We make great full-cast audio dramas and audiobooks that are available to buy on CD and/or download WE LOVE STORIES! SUBSCRIBERS GET Our audio productions are based on much-loved MORE! TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark If you subscribe, depending on the Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, range you subscribe to, you get free The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain audiobooks, PDFs of scripts, extra Scarlet and Survivors, as well as classics such as behind-the-scenes material, a HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The bonus release, downloadable audio Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also readings of new short stories and produce original creations such as Graceless, discounts. Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series including ATA Secure online ordering and details of Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & all our products can be found at: Sixpence Investigate and Blind Terror. www.bigfinish.com WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @ BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH HIS MONTH’S edition has proved to be one of the T biggest challenges I’ve had COMING SOON since I started writing Vortex – there was so much to fit in! (Especially when I realised I’d submitted 350 DORIAN GRAY extra words for two features!).