Fadi A. Bardawil REVOLUTION and DISENCHANT- MENT Th Eory in Forms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

United Nations Conciliation.Ccmmg3sionfor Paiestine

UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION.CCMMG3SIONFOR PAIESTINE RESTRICTEb Com,Tech&'Add; 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH APPENDIX J$ NON - JlXWISHPOPULATION WITHIN THE BOUNDARXESHELD BY THE ISRAEL DBFENCEARMY ON X5.49 AS ON 1;4-,45 IN ACCORDANCEWITH THE PALESTINE GOVERNMENT VILLAGE STATISTICS, APRIL 1945. CONTENTS Pages SUMMARY..,,... 1 ACRE SUB DISTRICT . , , . 2 - 3 SAPAD II . c ., * ., e .* 4-6 TIBERIAS II . ..at** 7 NAZARETH II b b ..*.*,... 8 II - 10 BEISAN l . ,....*. I 9 II HATFA (I l l ..* a.* 6 a 11 - 12 II JENIX l ..,..b *.,. J.3 TULKAREM tt . ..C..4.. 14 11 JAFFA I ,..L ,r.r l b 14 II - RAMLE ,., ..* I.... 16 1.8 It JERUSALEM .* . ...* l ,. 19 - 20 HEBRON II . ..r.rr..b 21 I1 22 - 23 GAZA .* l ..,.* l P * If BEERSHEXU ,,,..I..*** 24 SUMMARY OF NON - JEWISH'POPULATION Within the boundaries held 6~~the Israel Defence Army on 1.5.49 . AS ON 1.4.45 Jrr accordance with-. the Palestine Gp~ernment Village ‘. Statistics, April 1945, . SUB DISmICT MOSLEMS CHRISTIANS OTHERS TOTAL ACRE 47,290 11,150 6,940 65,380 SAFAD 44,510 1,630 780 46,920 TJBERIAS 22,450 2,360 1,290 26,100 NAZARETH 27,460 Xl, 040 3 38,500 BEISAN lT,92o 650 20 16,590 HAXFA 85,590 30,200 4,330 120,520 JENIN 8,390 60 8,450 TULJSAREM 229310, 10 22,320' JAFFA 93,070 16,300 330 1o9p7oo RAMIIEi 76,920 5,290 10 82,220 JERUSALEM 34,740 13,000 I 47,740 HEBRON 19,810 10 19,820 GAZA 69,230 160 * 69,390 BEERSHEBA 53,340 200 10 53,m TOT$L 621,030 92,060 13,710 7z6,8oo . -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Hezbollah, the Hidden Side of the Coin the Untold Story of Hezbollah

Hezbollah, the Hidden Side of the coin The untold Story of Hezbollah Written by : Massoud Mohamed Table of Contents: Research Question: ........................................................................................................................... 2 Is the Media hiding the truth or rather is it mediatizing a carefully crafted Hezbollah message? ............................................................................................................................................. 2 I. How did the Media present Hezbollah? ................................................................................ 2 II. To what extend is that true? And how Hezbollah managed to take over?.................. 2 The Story of Hezbollah which was never told: ........................................................................... 2 “Hezbollah” Significant Name: ........................................................................................... 3 The Islamic State (Shii vergin): ........................................................................................... 3 Why this specific name Hezbollah? .................................................................................. 3 Hezbollah Objectives: ........................................................................................................... 4 Our Objectives: ....................................................................................................................... 4 III. Promoting Hezbollah: ........................................................................................................... -

Nation, Village, Cave: a Spatial Reading of 1948 in Three Novels of Anton Shammas, Emile Habiby, and Elias Khoury

Nation, Village, Cave: A Spatial Reading of 1948 in Three Novels of Anton Shammas, Emile Habiby, and Elias Khoury Lital Levy Jewish Social Studies, Volume 18, Number 3, Spring/Summer 2012, pp. 10-26 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jss/summary/v018/18.3.levy.html Access provided by The Ohio State University (21 Apr 2014 17:35 GMT) Nation, Village, Cave: A Spatial Reading of 1948 in Three Novels of Anton Shammas, Emile Habiby, and Elias Khoury Lital Levy ABSTRACT Though written decades apart and in two different languages (Arabic and Hebrew), Emile Habiby’s The Pessoptimist, Anton Shammas’s Arabesques, and Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun are interrelated novels in a broader literary dialogue about 1948 and its aftermath for Palestinians. The novels’ respective narratives map the Palestinian experience onto spaces both larger and smaller than that of the nation, crossing borders between Lebanon, the Galilee, and the West Bank yet ultimately lo- cating the heart of each story in a highly symbolic space: the cave. In the three novels, the cave becomes an alternative Palestinian space or “underground homeland” that may represent the lost Palestine of the past, the hope for a better future, or knowledge of the self. It is also used to portray intergenerational tensions in the Palestinian story. Collapsing time and space, reality and fantasy, the cave functions as a spatial expres- sion of post-1948 Palestinian subjectivity. Keywords: caves, Emile Habiby, -

Laure Guirguis

THE ARAB LEFTS 66410_Guirguis.indd410_Guirguis.indd i 001/06/201/06/20 112:462:46 PPMM 66410_Guirguis.indd410_Guirguis.indd iiii 001/06/201/06/20 112:462:46 PPMM THE ARAB LEFTS Histories and Legacies, 1950s–1970s Edited by Laure Guirguis 66410_Guirguis.indd410_Guirguis.indd iiiiii 001/06/201/06/20 112:462:46 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation Laure Guirguis, 2020 © the chapters their several authors, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd T e Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5423 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5426 1 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5425 4 (epub) T e right of Laure Guirguis to be identif ed as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Published with the support of the University of Edinburgh Scholarly Publishing Initiatives Fund. 66410_Guirguis.indd410_Guirguis.indd iivv 001/06/201/06/20 112:462:46 PPMM CONTENTS Chapter Abstracts vii Acknowledgements xv Notes on Contributors xvi Introduction. -

Al Nakba Background

Atlas of Palestine 1917 - 1966 SALMAN H. ABU-SITTA PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY LONDON Chapter 3: The Nakba Chapter 3 The Nakba 3.1 The Conquest down Palestinian resistance to British policy. The The immediate aim of Plan C was to disrupt Arab end of 1947 marked the greatest disparity between defensive operations, and occupy Arab lands The UN recommendation to divide Palestine the strength of the Jewish immigrant community situated between isolated Jewish colonies. This into two states heralded a new period of conflict and the native inhabitants of Palestine. The former was accompanied by a psychological campaign and suffering in Palestine which continues with had 185,000 able-bodied Jewish males aged to demoralize the Arab population. In December no end in sight. The Zionist movement and its 16-50, mostly military-trained, and many were 1947, the Haganah attacked the Arab quarters in supporters reacted to the announcement of veterans of WWII.244 Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, killing 35 Arabs.252 On the 1947 Partition Plan with joy and dancing. It December 18, 1947, the Palmah, a shock regiment marked another step towards the creation of a The majority of young Jewish immigrants, men established in 1941 with British help, committed Jewish state in Palestine. Palestinians declared and women, below the age of 29 (64 percent of the first reported massacre of the war in the vil- a three-day general strike on December 2, 1947 population) were conscripts.245 Three quarters of lage of al-Khisas in the upper Galilee.253 In the first in opposition to the plan, which they viewed as the front line troops, estimated at 32,000, were three months of 1948, Jewish terrorists carried illegal and a further attempt to advance western military volunteers who had recently landed in out numerous operations, blowing up buses and interests in the region regardless of the cost to Palestine.246 This fighting force was 20 percent of Palestinian homes. -

The Palestinians in Israel Readings in History, Politics and Society

The Palestinians in Israel Readings in History, Politics and Society Edited by Nadim N. Rouhana and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury 2011 Mada al-Carmel Arab Center for Applied Social Research The Palestinians in Israel: Readings in History, Politics and Society Edited by: Nadim N. Rouhana and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury اﻟﻔﻠﺴﻄﻴﻨﻴﻮن ﰲ إﴎاﺋﻴﻞ: ﻗﺮاءات ﰲ اﻟﺘﺎرﻳﺦ، واﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﺔ، واملﺠﺘﻤﻊ ﺗﺤﺮﻳﺮ: ﻧﺪﻳﻢ روﺣﺎﻧﺎ وأرﻳﺞ ﺻﺒﺎغ-ﺧﻮري Editorial Board: Muhammad Amara, Mohammad Haj-Yahia, Mustafa Kabha, Rassem Khamaisi, Adel Manna, Khalil-Nakhleh, Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Mahmoud Yazbak Design and Production: Wael Wakeem ISBN 965-7308-18-6 © All Rights Reserved July 2011 by Mada Mada al-Carmel–Arab Center for Applied Social Research 51 Allenby St., P.O. Box 9132 Haifa 31090, Israel Tel. +972 4 8552035, Fax. +972 4 8525973 www.mada-research.org [email protected] 2 The Palestinians in Israel: Readings in History, Politics and Society Table of Contents Introduction Research on the Palestinians in Israel: Between the Academic and the Political 5 Areej Sabbagh-Khoury and Nadim N. Rouhana The Nakba 16 Honaida Ghanim The Internally Displaced Palestinians in Israel 26 Areej Sabbagh-Khoury The Military Government 47 Yair Bäuml The Conscription of the Druze into the Israeli Army 58 Kais M. Firro Emergency Regulations 67 Yousef Tayseer Jabareen The Massacre of Kufr Qassem 74 Adel Manna Yawm al-Ard (Land Day) 83 Khalil Nakhleh The Higher Follow-Up Committee for the Arab Citizens in Israel 90 Muhammad Amara Palestinian Political Prisoners 100 Abeer Baker National Priority Areas 110 Rassem Khamaisi The Indigenous Palestinian Bedouin of the Naqab: Forced Urbanization and Denied Recognition 120 Ismael Abu-Saad Palestinian Citizenship in Israel 128 Oren Yiftachel 3 Mada al-Carmel Arab Center for Applied Social Research Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to a group of colleagues who helped make possible the project of writing this book and producing it in three languages. -

ZOCHROT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 1 January 2015 – 31 December 2015

ZOCHROT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 1 January 2015 – 31 December 2015 Zochrot, RA 580-389526 1 Annual Narrative Report 2015 Reporting period: 1 January 2015 – 31 December 2015 1 Brief description of the genesis of the report The following report was written by Zochrot's resource development coordination. The information was collected from Zochrot's ongoing performance chart for 2015 and from discussions with the organization's director and the project coordinators; the coordinators also brought with them to these discussions feedback received from the projects' target audience during the period of this interim project. 2 Important changes that occurred with respect to Zochrot in the reporting period During the reporting period, a new position was added to the organization as part of the natural and positive process of the development and expansion of Zochrot's work. The position is the artistic director of 48mm international festival for films about the Nakba and Return. As the festival activity had been expending in the last 2 years, we had decided to locate a professional artistic director for the project in order professionalize the working process and increase the festival networks, internationally and locally. Zochrot’s activity scope in 2015. As can be clearly shown in the report below, Zochrot activity and public outreach had increased significantly in 2015 comparing to previous year (see especially our detailed indicators table in paragraph 4.1.2 in this report). In 2014 – we had about 22,485 direct beneficiaries, calculated as follows: 22,845 direct beneficiaries, calculated as follows: Information Centre: 480 people; 2 Exhibitions and lecture evenings – 180 people, Tours and commemoration events participants 1,320 people, Return Workshops – 177 people, Educators workshop and seminars – 120 people, open courses– 168 people, Truth Commission – 200 people, iNakba app users – 19,200 people, Film Festival – 1000 people. -

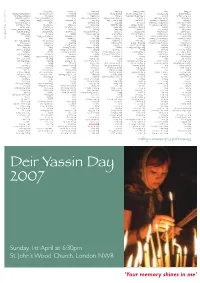

F-Dyd Programme

‘Your memory shines in me’ in shines memory ‘Your St. John’s Wood Church, London NW8 London Church, Wood John’s St. Sunday, 1st April at 6:30pm at April 1st Sunday, 2007 Deir Yassin Day Day Yassin Deir Destroyed Palestinian villages Amqa Al-Tira (Tirat Al-Marj, Abu Shusha Umm Al-Zinat Deir 'Amr Kharruba, Al-Khayma Harrawi Al-Zuq Al-Tahtani Arab Al-Samniyya Al-Tira Al-Zu'biyya) Abu Zurayq Wa'arat Al-Sarris Deir Al-Hawa Khulda, Al-Kunayyisa (Arab Al-Hamdun), Awlam ('Ulam) Al-Bassa Umm Ajra Arab Al-Fuqara' Wadi Ara Deir Rafat Al-Latrun (Al-Atrun) Hunin, Al-Husayniyya Al-Dalhamiyya Al-Birwa Umm Sabuna, Khirbat (Arab Al-Shaykh Yajur, Ajjur Deir Al-Shaykh Al-Maghar (Al-Mughar) Jahula Ghuwayr Abu Shusha Al-Damun Yubla, Zab'a Muhammad Al-Hilu) Barqusya Deir Yassin Majdal Yaba Al-Ja'una (Abu Shusha) Deir Al-Qasi Al-Zawiya, Khirbat Arab Al-Nufay'at Bayt Jibrin Ishwa', Islin (Majdal Al-Sadiq) Jubb Yusuf Hadatha Al-Ghabisyya Al-'Imara Arab Zahrat Al-Dumayri Bayt Nattif Ism Allah, Khirbat Al-Mansura (Arab Al-Suyyad) Al-Hamma (incl. Shaykh Dannun Al-Jammama Atlit Al-Dawayima Jarash, Al-Jura Al-Mukhayzin Kafr Bir'im Hittin & Shaykh Dawud) Al-Khalasa Ayn Ghazal Deir Al-Dubban Kasla Al-Muzayri'a Khirbat Karraza Kafr Sabt, Lubya Iqrit Arab Suqrir Ayn Hawd Deir Nakhkhas Al-Lawz, Khirbat Al-Na'ani Al-Khalisa Ma'dhar, Al-Majdal Iribbin, Khirbat (incl. Arab (Arab Abu Suwayrih) Balad Al-Shaykh Kudna (Kidna) Lifta, Al-Maliha Al-Nabi Rubin Khan Al-Duwayr Al-Manara Al-Aramisha) Jurdayh, Barbara, Barqa Barrat Qisarya Mughallis Nitaf (Nataf) Qatra Al-Khisas (Arab