ENTERING the 1980S: FISCAL POLICY CHOICES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download JANUARY 1980.Pdf

JANUARY 1980 ---,. LAW ENFORCEMENT BUllETIN JANUARY 1980, VOLUME 49, NUMBER 1 Contents Forensic Science 1 Speaker Identification (Part 1) Three Methods- Listening, Machine, and AuralVisual By Bruce E. Koenig, Special Agent, Technical Services Division, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Washington, D.C. 8 Hypnosis: The FBI's Team Approach By Richard L. Ault, Jr., Special Agent, Behavioral Science Unit, FBI Academy, Quantico, Va. Crime Problems 9 Automobile Theft: An Increasing Crime Problem By Samuel J. Rozzi, Commissioner of Police, Nassau County, N.Y. , and Det. Sgt. Richard Mueller, Police Department, Nassau County, N.Y. Facilities 14 The Canadian Police College By Charles W. Steinmetz, Special Agent, Education and Communication Arts Unit, FBI Academy, Quantico, Va. Point of View 19 Higher Education for Police Officers By Thomas A. Reppetto, Ph. D., Vice President and Professor of Criminal Justice Administration, John Jay College, New York, N.Y. The Legal Digest 28 The Constitutionality of Routine License Check Stops- A Review of Delaware v. Prouse By Daniel L. Schofield, Special Agent, Legal Counsel Division, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Washington, D.C. 2S Wanted by the FBI The Cover: Federal Bureau of Investigation Published by the Public Affairs Office, Voiceprintsfinger- United States Department of Justice Homer A. Boynton, Jr., prints of the future or Executive Assistant Director Washington, D.C. 20535 investigative tool for Editor-Thomas J. Deakin today? See story William H. Webster, Director Assistant Editor-Kathryn E. Sulewski page 1. Art Director-Carl A. Gnam, Jr. Writer/Editor-Karen McCarron The Attorney General has determined that the publication Production Manager-Jeffery L. -

Revitalization of Inner City Housing Through Property Tax Exemption: New York City’S J-51 to the Rescue Janice C

Urban Law Annual ; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law Volume 18 January 1980 Revitalization of Inner City Housing Through Property Tax Exemption: New York City’s J-51 to the Rescue Janice C. Griffith Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_urbanlaw Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Janice C. Griffith, Revitalization of Inner City Housing Through Property Tax Exemption: New York City’s J-51 to the Rescue, 18 Urb. L. Ann. 153 (1980) Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_urbanlaw/vol18/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Law Annual ; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVITALIZATION OF INNER CITY HOUSING THROUGH PROPERTY TAX EXEMPTION AND ABATEMENT: NEW YORK CITY'S J-51 TO THE RESCUE* JANICE C GRIFFITH* * I. INTRODUCTION A. The Rental Housing Situation in New York City in 1975 When the municipal bond market closed its door to New York City in the spring of 1975,' it shut out the city's program of providing mortgage loans to finance newly constructed and rehabilitated hous- ing for low- and middle-income people. New York City could no longer act as a banker; the principal resource upon2 which the city had relied to solve its housing problems was gone. Despite the infusion of more than one billion dollars over twenty * The opinions expressed in this Article are those of the author and do not neces- sarily represent those of New York City. -

Maps Cited by Congress When Designating Wilderness

Maps Summary Table In 2003 long-time NPS Wilderness Coordinator Wes Henry prepared this table that was intended for inclusion in the updated Reference Manual 41 – Wilderness Management. Wes died soon thereafter. PEER has updated the table to reflect information through 2014. RM 41: Section F: DRAFT January 21, 2003 Maps Cited by Congress when Designating Wilderness. The table lists in: Column 2: maps cited by Congress when designating NPS wilderness (in chronological order by date of enactment); Column 3: date of an official legal description prepared after designation, and Column 4: whether a post-enactment official boundary map was prepared. NPS AREA – CONGRESSIONAL DATE OF DATE OF WILDERNESS MAP NUMBER OFFICIAL OFFICAL MAP DATE AND DATE, CITED LEGAL IN LAW DESCRIPTION Craters of the 131-91,000 December 1970 NPS cited Moon – Oct. 1970 March 1970 legislative map Petrified Forest - NP-PF-3320-O December 1970 NPS cited October 1970 November 1967 legislative map Lava Beds – NM-LB-3227H December 1972 NPS cited October 1972 August 1972 legislative map Lassen Volcanic – NP-LV-9013C June 1973 NPS cited October 1972 August 1972 legislative map Point Reyes – 612-90,000-B May 1978 February 1977 October 1976 September 1976 Bandelier – 315-20,014-B August 1978 August 1978 October 1976 May 1976 Black Canyon of 144-20,017 January 1977 January 1977 the Gunnison – May 1973 October 1976 Chiricahua - 145-20,007-A May 1978 January 1977 October 1976 September 1973 Great Sand Dunes 140-20,006-C December 1976; January 1980 October 1976 February 1976 Revised: -

WHCA Video Log

WHCA Video Log Tape # Date Title Format Duration Network C1 9/23/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #1 (Tape 1) In Philadelphia, Domestic Issues BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 ABC C2 9/23/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #1 (Tape 2) In Philadelphia, Domestic Issues BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C3 10/6/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #2 In San Francisco, Foreign Policy BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 ABC C4 10/15/1976 Mondale/Dole Debate BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 NBC C5 10/17/1976 Face the Nation with Walter Mondale BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C6 10/22/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #3 At William & Mary, not complete BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 NBC C7 11/1/1976 Carter Election Special BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C8 11/3/1976 Composite tape of Carter/Mondale activities 11/2-11/3/1976 BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C9 11/4/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ALL C10 11/7/1976 Ski Scene with Walter Mondale BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 WMAL C11 11/7/1976 Agronsky at Large with Mondale & Dole BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 WETA C12 11/29/1976 CBS Special with Cronkite & Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C13 12/3/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ALL C14 12/13/1976 Mike Douglas Show with Lillian and Amy Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 CBS C15 12/14/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ALL C16 12/14/1976 Barbara Walters Special with Peters/Streisand and Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ABC Page 1 of 92 Tape # Date Title Format Duration Network C17 12/16/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C18 12/21/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ALL C19 12/23/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C20 12/29/1976 Good Morning America with Carter and Cabinet Members (Tape 1) BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ABC C21 12/29/1976 Good Morning America with Carter and Cabinet Members (Tape 2) Digital Files, Umatic 60 ABC C22 1/4/1977 Dinah Shore Show with Mrs. -

TREASURY FINANCING REQUIREMENTS October - December 1979 $Bil

TREASURY FINANCING REQUIREMENTS October - December 1979 $Bil. $Bil. Uses Sources Redemptions of Special Issues ^^ 51 y2 %Gov't Account Sales Y2 Vl 50 50 40 — Coupon Maturities | 4 Coupon Refundings —40 Foreign Savings Bonds Nonmarketables 30 30 1 Va 20 Net Market Borrowingt 20 i Cash Deficit 10 10 Decrease in Cash Balance | 0 0 11 Includes maturing marketable securities of $'/4 billion. Office of the Secretary of the Treasury Office of Government Financing January 29, 1980-19 TREASURY FINANCING REQUIREMENTS January - March 1980^ $Bil. $Bil. Uses Sources Redemptions of Special Issues ^^^^___r_„_^^^^ Gov't Account Sales 40- 40 Coupon Maturities | I Coupon Refundings Foreign Nonmarketables: 30 Nonmarketables 30 Savings Bonds | Done 20- 1/4 20 State & Local Net Market Borrowing To Be Done I Cash Deficit 10 10 Decrease in Cash Balance t 0 ^Assumes $8 Billion March 31, 1980 Cash Balance. Office of the Secretary of the Treasury Office of Government Financing January 29, 1980-12 TREASURY OPERATING CASH BALANCE Semi-Monthly $Bil. Without — New Borrowing 4 Total Operating 20 ^ Balance 15 Tax and Loan a Accounts Balance w< 10 t>w'<''i>HWB/ Federal Reserve Account 0 -5 Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May Jun. Jul. Aug. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. 1979 1980 Office of the Secretary of the Treasury Office of Government Financing January 29, 1980-13 TREASURY NET MARKET BORROWING^ Calendar Year Quarters $Bil. $Bil. COUPONS 24.7 MlOver 10 yrs. 23.9 ^0-10 yrs. BILLS 20 20 10 10 0 -10 -3.9 -10 I II III IV I II III IV I II III IV I II III IV I II III IV I 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1/ Excludes Federal Reserve and Government Account Transactions. -

The Winter Season December 1, 1980 -- February 28, 1981

CONTINENT,\IJ SURVEY The Winter Season December 1, 1980 -- February 28, 1981 Abbreviations frequently used in Regional Reports ad.: adult, Am.: American, c.: central, C: Celsius, CBC: Refuge, Res.: Reservoir, not Reservation, R.: River, S.P.: Christmas Bird Count, Cr.: Creek, Corn. Common, Co.: State Park, sp.: species,spp.: speciesplural, ssp.: subspecies, County, Cos.: Counties, et aL: and others, E.: Eastern (bird lwp.: Township, W.: Western (bird name), W.M.A.: Wildlife name),Eur.: European, Eurasian, F: Fahrenheit,fide:rcport- Management Area, v.o.: various observers, N,S,W,E,: direc- ed by, F.&W.S.: Fish & Wildlife Servicc,Ft.: Fort, imm.: im- tion of motion, n., s., w., e.: direction of location, >: more mature, 1.: Island, Is.: Islands, Isles, Jet.: Junction, juv.: than, <: fewer than, _+: approximately, or estimated number, juvenile, L.: Lake, m.ob.: many observers, Mr.: Mountain, cr: male, 9: female, •: imm. or female, *: specimen, ph.: Mrs.: Mountains, N.F.: National Forest, N.M.: National photographed, ]': documented, ft: feet, mi: miles, m: meters, Monument, N.P.: National Park, N.W.R.: Nat'l Wildlife kin: kilometers, date with a + (e.g., Mar. 4+): recorded Refuge, N.: Northern (bird name), Par.: Parish, Pen.: Penin- beyond that date. Editors may also abbreviate often-cited sula, P.P.: Provincial Park, Pt.: Point, not Port, Ref.: locations or organizations. NORTHEASTERN MARITIME noses were scarce or were not adequatelyre- REGION ported; 15 N. Fulmar / Peter D. Vickery were seen off Rockport, Mass., Feb. 7 (fide RPE). Two imm. Great Cormorants were unus- This winter was one of the quietest in re- ual inland along the Ag- cent years. -

Why We Are Not Facing Another 1980S-Style Farm Sector Crisis (PDF)

Why we are not facing another Economics Report 1980s-style farm sector crisis Farm Credit Administration Office of Regulatory Policy Agricultural and Economic Policy Team Net farm income in 2017 is forecast by USDA to decline for a fourth August 1, 2017 consecutive year. Global supplies of many grains and oilseeds are burdensome, leading to low prices. Farm debt continues to climb while Summary Midwestern farmland values continue to decline. These conditions are leading many observers to ask whether agriculture is heading for a crisis The current downturn in the farm economy has some similarities to the akin to the crisis experienced in the 1980s. crisis that occurred in the 1980s. But Although today’s conditions display some similarities to the crisis of the there are also important differences. These differences make it highly 1980s, there are also many important differences. See Appendix A. Indeed, unlikely that the current downturn it is possible that financial conditions in the farm economy may deteriorate will evolve into a crisis of the further, but it is unlikely that we will see conditions deteriorate to anything magnitude experienced in the 1980s. remotely resembling the 1980s crisis. Prior to both periods, commodity The Golden 1970s prices, farm incomes, and farmland values boomed in response to a The crisis was preceded by what might be considered the golden era of the sharp increase in the demand for 1970s. Farm exports surged in the 1970s due to, among other reasons, a farm commodities. The boom periods weak dollar, unexpected demand from the Soviet Union (the Russian wheat were then followed by substantial deal), and a shortage of fishmeal, which is a protein supplement for animal declines in prices, incomes, and farmland values. -

Earthquakes in the United States January-March 1980

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 853-A Earthquakes in the United States January-March 1980 Earthquakes in the United States January-March 1980 By C. W. Stover, J. H. Minsch, B. G. Reagor, and P. K. Smith GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 853-A 1981 United States Department of the Interior JAMES G. WATT, Secretary Geological Survey Doyle G. Frederick, Acting Director Free on application to the Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey, 604 South Pickett Street, Alexandria, VA 22304 CONTENTS Page Introduction................................................................. A1 Discussion of tables......................................................... 1 Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale of 1931.................................... 8 Acknowledgments.............................................................. 41 References cited............................................................. 41 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. "Earthquake Report" form.......................................... A2 2. Map showing standard time zones of the conterminous United States. 4 3. Map showing standard time zones of Alaska and Hawaii.............. 5 4. Map of earthquake epicenters in the conterminous United States for January-March 1980............ •• • • • • • • • • • • • •• •• • • • • •• • • •• • •• • • • •• • 6 5. Map of earthquake epicenters in Alaska for January-March 1980..... 7 6. Map of earthquake epicenters in Hawaii for January-March 1980..... 8 7. Isoseismal map for the central California earthquake of 24 January 1980...................... •• • • • • • •• -

FLAG and the Diplomacy of the Iran Hostage Families

Daniel Strieff FLAG and the diplomacy of the Iran hostage families Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Strieff, Daniel (2017) FLAG and the diplomacy of the Iran hostage families. Diplomacy and Statecraft, 28 (4). pp. 702-725. ISSN 0959-2296 DOI: 10.1080/09592296.2017.1386465 © 2017 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/86833/ Available in LSE Research Online: February 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. 1 FLAG and the Diplomacy of the Iran Hostage Families Daniel Strieff Abstract. The extraordinary public diplomacy carried out by the families of the American hostages held in Iran from 1979-1981 played a pivotal role in domesticating and humanising the biggest foreign policy crisis of Jimmy Carter’s presidency. -

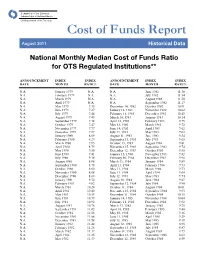

Historical Data

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks US Department of the Treasury Cost of Funds Report August 2011 Historical Data National Monthly Median Cost of Funds Ratio for OTS Regulated Institutions** ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX DATE MONTH RATE% DATE MONTH RATE% N.A. January 1979 N.A. N.A. June 1982 11.38 N.A. February 1979 N.A. N.A. July 1982 11.54 N.A. March 1979 N.A. N.A. August 1982 11.50 N.A. April 1979 N.A. N.A. September 1982 11.17 N.A. May 1979 7.35 December 14, 1982 October 1982 10.91 N.A. June 1979 7.27 January 12, 1983 November 1982 10.62 N.A. July 1979 7.44 February 11, 1983 December 1982 10.43 N.A. August 1979 7.49 March 14, 1983 January 1983 10.14 N.A. September 1979 7.38 April 12, 1983 February 1983 9.75 N.A. October 1979 7.47 May 13, 1983 March 1983 9.72 N.A. November 1979 7.77 June 14, 1983 April 1983 9.62 N.A. December 1979 7.87 July 13, 1983 May 1983 9.62 N.A. January 1980 8.09 August 11, 1983 June 1983 9.54 N.A. February 1980 8.29 September 13, 1983 July 1983 9.65 N.A. March 1980 7.95 October 13, 1983 August 1983 9.81 N.A. April 1980 8.79 November 15, 1983 September 1983 9.74 N.A. May 1980 9.50 December 12, 1983 October 1983 9.85 N.A. -

Download (4Mb)

European Community is published on behalf of the Commission of the European Communities. Into the eighties pages3-6 London Office: 20 Kensington Peggy Crane recalls Community Palace Gardens, London W8 4QQ Tel (01) 727 8090 achievements in 1979 and singles out challenges for the 1980s Cardiff Office: 4 Cathedral Road, Cardiff CF! 9SG Tel. (0222) 371631 Sun Power pages 7-8 Solar energy could provide a lifeline Edinburgh Office: 7 Alva Streel , Edinburgh EH2 4PH for developing countries Tel. (031) 225 2058 lnlended to give a concise view of Reforming the Commission pages 9-11 current Communily affairs and The Spierenbourg report stimulate discussion on European recommends streamlining before problems, it does nol necessarily reflecl 1he opinions of the new member states arrive Communily institulions or of its edi1or. Unsigned articles may be Jobs pages 12-13 quoted or reprinted withou[ Work-sharing and sandwich payment if their source is acknowledged. Righls in signed courses both help reduce articles should be negotiated with unemployment I heir au I hors. In either case, the edi1or would be glad to receive the In theswim pages l4-15 publication. The Community helps clean up Printed by Edwin Snetl printers, British beaches Yeovil England European Community also appears in lhe following edit ions: Ru naway CAP page 16 Community Report, 29 Merrion Principles of the agricultural policy Square, Dublin 2, Ireland Tel. 760353 still right but costs must be European Community, 2100 M controlled Street, NW, Suite 707, Washington DC 20037, USA Tel. 202 8629500 30 lours d'Europe, 61 rue des Belles Feuilles, 75782 Paris Cedex 16, France. -

The Records of the Women's City Club of New York, Inc. 1915

The Records of the Women’s City Club of New York, Inc. 1915 - 2011 Finding Aid, 3rd Revised Edition Former headquarters of the Women’s City Club of New York at 22 Park Avenue, N.Y.C. ArchivesArchives andand SpecialSpecial CollectionsCollections TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information 3 Presidents of the Women’s City Club of New York, Inc. 4 - 5 Historical Note 6 Scope and Content Note 7 - 8 Series Description 9 - 13 Container List 14 - 85 Addenda I 86 - 120 Addenda II 121 - 137 Addenda III 138 - 150 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Accession Number: 94 - 03 Size: 104 cu. ft. Provenance: The Women’s City Club of New York, Inc. Restrictions: The audiotapes and videotapes in boxes 42 - 48, 154, and 222 - 225 are inaccessible to researchers until they are transferred to another medium. Location: Range 14 Sections 8 - 13 Archivist: Prof. Julio L. Hernandez-Delgado Assistants: Maggie Desgranges Maria Enaboifo Dane Guerrero Nefertiti Guzman Yvgeniy Kats Christina Melendez - Lawrence Phuong Phan Bich Manuel Rimarachin Date: July 1994 Revised: October 2013 3 Presidents of the Women’s City Club of New York, Inc. Name Term Mrs. Alice Duer Miller 1916 Mrs. Learned Hand (Frances Fricke Hand) 1916 - 1917 Mrs. Ernest C. Poole (Margaret Winterbotham Poole) 1917 - 1918 Mrs. Mary Garrett Hay 1918 - 1924 Mrs. H. Edward Dreier (Ethel E. Drier) 1924 - 1930 Mrs. Martha Bensley Bruere 1930 - 1932 Mrs. H. Edward Dreier (Ethel E. Drier) 1932 - 1936 Mrs. Samuel Sloan Duryee (Mary Ballard Duryee) 1936 - 1940 Miss Juliet M. Bartlett 1940 - 1942 Mrs. Alfred Winslow Jones (Mary Carter Jones) 1942 - 1946 Hon.