PDF Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papiers Des Chefs De L'etat. Ive République (1947-1959)

Papiers des chefs de l'Etat. IVe République (1947-1959) Répertoire (4AG/1-4AG/718) Par F. Adnès Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2001 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_003848 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise Numen dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives n ationales 2 Archives nationales (France) Préface Notices biographiques Liens : Liens annexes : • Notices biographiques 3 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 4AG/1-4AG/718 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Papiers des chefs de l'Etat. Ive République Date(s) extrême(s) 1947-1959 Localisation physique Pierrefitte DESCRIPTION Présentation du contenu Si les équipes ministérielles ont témoigné de quelque permanence, le massacre des premiers ministres a fait qu'aucun d'eux ne pouvait se maintenir au pouvoir. En face de ce personnage perpétuellement changeant, le président de la République demeurait immuable, étant seul à avoir, depuis le début, connu et suivi toutes les affaires, toutes les négociations, dans un courant interrompu. Quand il y avait crise, puis reprise de l'action politique après rupture de charge, c'était l'Élysée seul qui, pour enchaîner, offrait une rampe solide à quoi s'accrocher. André Siegfried De la IVe à la Ve République au jour le jour, Paris, Plon, 1958, p. 201. Cet inventaire présente à l'historien des sources de nature extrêmement différente, reflet des multiples activités de la présidence de la République de 1947 à 1958, et dont l'intérêt déborde souvent le cadre assigné à celle-ci par la Constitution du 27 octobre 1946. -

Timeline / Before 1800 to 1900 / AUSTRIA / POLITICAL CONTEXT

Timeline / Before 1800 to 1900 / AUSTRIA / POLITICAL CONTEXT Date Country Theme 1797 Austria Political Context Austria and France conclude the Treaty of Campo Formio on 17 October. Austria then cedes to Belgium and Lombardy. To compensate, it gains the eastern part of the Venetian Republic up to the Adige, including Venice, Istria and Dalmatia. 1814 - 1815 Austria Political Context The Great Peace Congress is held in Vienna from 18 September 1814 to 9 June 1815. Clemens Wenzel Duke of Metternich organises the Austrian predominance in Italy. Austria exchanges the Austrian Netherlands for the territory of the Venetian Republic and creates the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia. 1840 - 1841 Austria Political Context Austria cooperates in a settlement to the Turkish–Egyptian crisis of 1840, sending intervention forces to conquer the Ottoman fortresses of Saida (Sidon) and St Jean d’Acre, and concluding with the Dardanelles Treaty signed at the London Straits Convention of 1841. 1848 - 1849 Austria Political Context Revolution in Austria-Hungary and northern Italy. 1859 Austria Political Context Defeat of the Austrians by a French and Sardinian Army at the Battle of Solferino on 24 June sees terrible losses on both sides. 1859 Austria Political Context At the Peace of Zürich (10 November) Austria cedes Lombardy, but not Venetia, to Napoleon III; in turn, Napoleon hands the province over to the Kingdom of Sardinia. 1866 Austria Political Context Following defeat at the Battle of Königgrätz (3 October), at the Peace of Vienna, Austria is forced to cede the Venetian province to Italy. 1878 Austria Political Context In June the signatories at the Congress of Berlin grant Austria the right to occupy and fully administer Bosnia and Herzegovina for an undetermined period. -

THE PORTRAYAL of the REIGN of MAXIMILIM M B GARLQTA ' 'BI THREE OONTEMPOMRX MEXICM Plabffilghts ' By- Linda E0 Haughton a Thesis

The portrayal of the reign of Maximilian and Carlota by three contemporary Mexican playwrights Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Haughton, Linda Elizabeth, 1940- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 12:42:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318919 THE PORTRAYAL OF THE REIGN OF MAXIMILIM MB GARLQTA ' 'BI THREE OONTEMPOMRX MEXICM PLABffilGHTS ' by- Linda E0 Haughton A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements • ' ■ i For the Degree of MASTER OF .ARTS In the Graduate College , THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1962 STATEMENT b y au t h o r This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to bor rowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Verona Family Bike + Adventure Tour Lake Garda and the Land of the Italian Fairytale

+1 888 396 5383 617 776 4441 [email protected] DUVINE.COM Europe / Italy / Veneto Verona Family Bike + Adventure Tour Lake Garda and the Land of the Italian Fairytale © 2021 DuVine Adventure + Cycling Co. Hand-craft fresh pasta during an evening of Italian hospitality with our friends Alberto and Manuela Hike a footpath up Monte Baldo, the mountain above Lake Garda that offers the Veneto’s greatest views Learn the Italian form of mild mountaineering known as via ferrata Swim or sun on the shores of Italy’s largest lake Spend the night in a cozy refuge tucked into the Lessini Mountains, the starting point for a hike to historic WWI trenches Arrival Details Departure Details Airport City: Airport City: Milan or Venice, Italy Milan or Venice, Italy Pick-Up Location: Drop-Off Location: Porta Nuova Train Station in Verona Porta Nuova Train Station in Verona Pick-Up Time: Drop-Off Time: 11:00 am 12:00 pm NOTE: DuVine provides group transfers to and from the tour, within reason and in accordance with the pick-up and drop-off recommendations. In the event your train, flight, or other travel falls outside the recommended departure or arrival time or location, you may be responsible for extra costs incurred in arranging a separate transfer. Emergency Assistance For urgent assistance on your way to tour or while on tour, please always contact your guides first. You may also contact the Boston office during business hours at +1 617 776 4441 or [email protected]. Younger Travelers This itinerary is designed with children age 9 and older in mind. -

Unification of Italy 1792 to 1925 French Revolutionary Wars to Mussolini

UNIFICATION OF ITALY 1792 TO 1925 FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS TO MUSSOLINI ERA SUMMARY – UNIFICATION OF ITALY Divided Italy—From the Age of Charlemagne to the 19th century, Italy was divided into northern, central and, southern kingdoms. Northern Italy was composed of independent duchies and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Papal States of central Italy were ruled by the Pope; and southern Italy had been ruled as an independent Kingdom since the Norman conquest of 1059. The language, culture, and government of each region developed independently so the idea of a united Italy did not gain popularity until the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars wreaked havoc on the traditional order. Italian Unification, also known as "Risorgimento", refers to the period between 1848 and 1870 during which all the kingdoms on the Italian Peninsula were united under a single ruler. The most well-known character associated with the unification of Italy is Garibaldi, an Italian hero who fought dozens of battles for Italy and overthrew the kingdom of Sicily with a small band of patriots, but this romantic story obscures a much more complicated history. The real masterminds of Italian unity were not revolutionaries, but a group of ministers from the kingdom of Sardinia who managed to bring about an Italian political union governed by ITALY BEFORE UNIFICATION, 1792 B.C. themselves. Military expeditions played an important role in the creation of a United Italy, but so did secret societies, bribery, back-room agreements, foreign alliances, and financial opportunism. Italy and the French Revolution—The real story of the Unification of Italy began with the French conquest of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. -

O Du Mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in The

O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Jason Stephen Heilman 2009 Abstract As a multinational state with a population that spoke eleven different languages, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was considered an anachronism during the age of heightened nationalism leading up to the First World War. This situation has made the search for a single Austro-Hungarian identity so difficult that many historians have declared it impossible. Yet the Dual Monarchy possessed one potentially unifying cultural aspect that has long been critically neglected: the extensive repertoire of marches and patriotic music performed by the military bands of the Imperial and Royal Austro- Hungarian Army. This Militärmusik actively blended idioms representing the various nationalist musics from around the empire in an attempt to reflect and even celebrate its multinational makeup. -

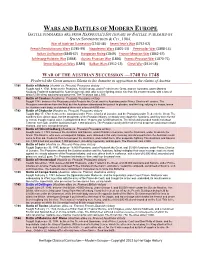

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Cluster Book 9 Printers Singles .Indd

PROTECTING EDUCATION IN COUNTRIES AFFECTED BY CONFLICT PHOTO:DAVID TURNLEY / CORBIS CONTENT FOR INCLUSION IN TEXTBOOKS OR READERS Curriculum resource Introducing Humanitarian Education in Primary and Junior Secondary Education Front cover A Red Cross worker helps an injured man to a makeshift hospital during the Rwandan civil war XX Foreword his booklet is one of a series of booklets prepared as part of the T Protecting Education in Conflict-Affected Countries Programme, undertaken by Save the Children on behalf of the Global Education Cluster, in partnership with Education Above All, a Qatar-based non- governmental organisation. The booklets were prepared by a consultant team from Search For Common Ground. They were written by Brendan O’Malley (editor) and Melinda Smith, with contributions from Carolyne Ashton, Saji Prelis, and Wendy Wheaton of the Education Cluster, and technical advice from Margaret Sinclair. Accompanying training workshop materials were written by Melinda Smith, with contributions from Carolyne Ashton and Brendan O’Malley. The curriculum resource was written by Carolyne Ashton and Margaret Sinclair. Booklet topics and themes Booklet 1 Overview Booklet 2 Legal Accountability and the Duty to Protect Booklet 3 Community-based Protection and Prevention Booklet 4 Education for Child Protection and Psychosocial Support Booklet 5 Education Policy and Planning for Protection, Recovery and Fair Access Booklet 6 Education for Building Peace Booklet 7 Monitoring and Reporting Booklet 8 Advocacy The booklets should be used alongside the with interested professionals working in Inter-Agency Network for Education in ministries of education or non- Emergencies (INEE) Minimum Standards for governmental organisations, and others Education: Preparedness, Response, Recovery. -

Adrian Woll: Frenchman in the Mexican Military Service

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 33 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-1958 Adrian Woll: Frenchman in the Mexican Military Service Joseph Milton Nance Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Nance, Joseph Milton. "Adrian Woll: Frenchman in the Mexican Military Service." New Mexico Historical Review 33, 3 (1958). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol33/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. NEW MEXICO HISTORlCAL REVIEW VOL. XXXIII JULY, 1958 NO.3 ADRIAN WOLL: FRENCHMAN IN THE MEXICAN MILITARY SERVICE By JOSEPH MILTON NANCE* HIS is a biographical sketch of a rather prominent and T influential "soldier of fortune" whose integrity, honesty, attention to duty, and gentlemanly conduct most Texans of the days of the Republic respected, even if they disliked the government he so often represented. Adrian Won was born a Frenchman on December 2, 1795, in St. Germain-en-Laye, near Paris, and educated for the military profession. He served under the First Empire as a lieutenant of a regiment of lancers of the imperial guard.1 Since his regiment was composed largely of Poles, won has sometimes mistakenly been represented as being of Polish nationality. In 1815 he was captain adjutant major in the 10th Legion of the National Guard of the Seine.2 Upon the restoration of the Bourbons in France, won went to New York, thence to Baltimore, Maryland, with letters of intro duction to General Winfield Scott who befriended him and, no doubt, pointed out to him the wonderful opportunities offered by the revolutionary disturbances in Mexico to a young man of energy, skilled in the arts of a soldier. -

Josã© Antonio Ulloa Collection of Cartes De Visite

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8g44wcf No online items José Antonio Ulloa collection of cartes de visite Finding aid prepared by Carlota Ramirez, Student Processing Assistant. Special Collections & University Archives The UCR Library P.O. Box 5900 University of California Riverside, California 92517-5900 Phone: 951-827-3233 Fax: 951-827-4673 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/libraries/special-collections-university-archives © 2017 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. José Antonio Ulloa collection of MS 027 1 cartes de visite Descriptive Summary Title: José Antonio Ulloa collection of cartes de visite Date (inclusive): circa 1858-1868 Collection Number: MS 027 Creator: Ulloa, José Antonio Extent: 0.79 linear feet(2 boxes) Repository: Rivera Library. Special Collections Department. Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Abstract: This collection consists of 60 cartes de visite, owned by José Antonio Ulloa of Zacatecas, Mexico. Items in the collection include photographs and portraits of European, South American, and Central American royalty and military members from the 19th century. Many of the cartes de visite depict members of European royalty related to Napoleon I, as well as cartes de visite of figures surrounding the trial and execution of Mexican Emperor Maximilian I in 1867. Languages: The collection is mostly in Spanish, with some captions in French and English. Access The collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright Unknown: Some materials in these collections may be protected by the U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17, U.S.C.). In addition, the reproduction, and/or commercial use, of some materials may be restricted by gift or purchase agreements, donor restrictions, privacy and publicity rights, licensing agreement(s), and/or trademark rights. -

U.S. Military Advisory Effort in Vietnam: Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, 1950-1964

http://gdc.gale.com/archivesunbound/ U.S. MILITARY ADVISORY EFFORT IN VIETNAM: MILITARY ASSISTANCE ADVISORY GROUP, VIETNAM, 1950-1964 President Harry Truman had approved National Security Council (NSC) Memorandum 64 in March 1950, proclaiming that French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) was a key area that could not be allowed to fall to the communists and that the U.S. would provide support against communist aggression in the area. However, NSC 64 did not identify who would receive the aid, the French or the South Vietnamese. The French did not want the aid to go directly to the South Vietnamese and opposed the presence of any American advisory group. Nevertheless, the U.S. government argued that such a team would be necessary to coordinate requisitioning, procurement, and dissemination of supplies and equipment. Accordingly, an advisory group was dispatched to Saigon. In the long run, however, the French high command ignored the MAAG in formulating strategy, denied them any role in training the Vietnamese, and refused to keep them informed of current operations and future plans. By 1952, the U.S. would bear roughly one-third of the cost of the war the French were fighting, but find itself with very little influence over French military policy in Southeast Asia or the way the war was waged. Ultimately, the French were defeated at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and withdraw from Vietnam, passing the torch to the U.S. In 1964, MAAG Vietnam would be disbanded and its advisory mission and functions integrated into the U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), which had been established in February 1962. -

From Dooradoyle to the Elysee Palace

meZife anb IICimes: of $%xrie CEbme Batrice he Irish have been a wander- Burgundy. There he met and married ing people since the days bp Dr. meb$otter Charlotte D'Eguilly, a noblewoman and when Irish Kings, such as one of the richest heiresses in Burgundy. Niall of the Nine Hostages Jean Baptiste (as he was known in France) led piratical raids into the home. One of the sons, John Baptist, was a commoner married into the nobility dying Roman Empire. One of the most trainedasamedicaldoctorandpracticed and,inaccordancewiththestrict interesting phases of the history of the in the town of Autun, near Dijon, capital of regulations of the ancient regime (pre- Irish abroad is the period of the Wild Geese. Between the Treaty of Limerick (1691) and the outbreak of the French Revolution (1789) many thousands of Irishmen (and Irish women) emigrated to the continent of Europe. They entered the service of the great European monarchies and several of them rose to high rank in both the armed forces and the civil government of their adopted countries. The exiled Irish nobility and gentry became assimilated into the rarefied, cosmopolitan world of the European aristocracy. The descendants of the Wild Geese continued to flourish in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These statesmen of Irish descent held very high office in nineteenth century Europe. Leopoldo O'Donnell, Duke of Tetuan (1809-67) was prime minister of Spain in 1856 and again from 1858 to 1863. Eduard, Count Taaffe (1833-95) was prime minister of the Austrian Empire from 1879 to 1893. The third of these statesmen was Marie Edme Patrice Maurice de McMahon, Duc de Magenta, (1808-93), who was president of France from 1873 to 1879.