The Sugar Industry on the Sunshine Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SC6.10 Planning Scheme Policy for Heritage and Character Areas Overlay Code SC6.10.1 Purpose

SC6.10 Planning scheme policy for heritage and character areas overlay code SC6.10.1 Purpose The purpose of this planning scheme policy is to:- (a) provide advice about achieving outcomes in the Heritage and character areas overlay code; and (b) identify information that may be required to support a development application where affecting a heritage place or neighbourhood character area. Note—nothing in this planning scheme policy limits Council’s discretion to request other relevant information in accordance with the Act. Note—the Heritage and character areas overlay code and the Planning scheme policy for heritage and character areas code does not apply to:- (a) Aboriginal cultural heritage which is protected under the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 and which is subject to a cultural heritage duty of care; and (b) State heritage places or other areas which are protected under the Queensland Heritage Act 1992. SC6.10.2 Application This planning scheme policy applies to assessable development which requires assessment against the Heritage and character areas overlay code. SC6.10.3 Advice for local heritage places and development adjoining a State or local heritage place outcomes The following is advice for achieving outcomes in the Heritage and character areas overlay code relating to local heritage places and development adjoining a State or local heritage place:- (a) State and local heritage places have significant cultural significance and are important to the community as places that provide direct contact with evidence from -

Maroochy River Environmental Values and Water Quality

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! M A R O O C H Y R I V E R , I N C L U D I N G A L L T R I B U T A R I E S O F ! T H E R I V E R ! ! M A R O O C H Y R I V E R , I N C L U D I N G A L L T R I B U T A R I E S O F T H E R I V E R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Part of Basin 141 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 152°50'E 153°E ! 153°10'E ! ! -

Land Cover Change in the South East Queensland Catchments Natural Resource Management Region 2010–11

Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts Land cover change in the South East Queensland Catchments Natural Resource Management region 2010–11 Summary The woody vegetation clearing rate for the SEQ region for 10 2010–11 dropped to 3193 hectares per year (ha/yr). This 9 8 represented a 14 per cent decline from the previous era. ha/year) 7 Clearing rates of remnant woody vegetation decreased in 6 5 2010-11 to 758 ha/yr, 33 per cent lower than the previous era. 4 The replacement land cover class of forestry increased by 3 2 a further 5 per cent over the previous era and represented 1 Clearing Rate (,000 26 per cent of the total woody vegetation 0 clearing rate in the region. Pasture 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 remained the dominant replacement All Woody Clearing Woody Remnant Clearing land cover class at 34 per cent of total clearing. Figure 1. Woody vegetation clearing rates in the South East Queensland Catchments NRM region. Figure 2. Woody vegetation clearing for each change period. Great state. Great opportunity. Woody vegetation clearing by Woody vegetation clearing by remnant status tenure Table 1. Remnant and non-remnant woody vegetation clearing Table 2. Woody vegetation clearing rates in the South East rates in the South East Queensland Catchments NRM region. Queensland Catchments NRM region by tenure. Woody vegetation clearing rate (,000 ha/yr) of Woody vegetation clearing rate (,000 ha/yr) on Non-remnant Remnant -

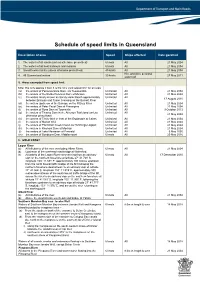

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

Principles and Tools for Protecting Australian Rivers

Principles and Tools for Protecting Australian Rivers N. Phillips, J. Bennett and D. Moulton The National Rivers Consortium is a consortium of policy makers, river managers and scientists. Its vision is to achieve continuous improvement in the health of Australia’s rivers. The role of the consortium is coordination and leadership in river restoration and protection, through sharing and enhancing the skills and knowledge of its members. Partners making a significant financial contribution to the National Rivers Consortium and represented on the Board of Management are: Land & Water Australia Murray–Darling Basin Commission Water and Rivers Commission, Western Australia CSIRO Land and Water Published by: Land & Water Australia GPO Box 2182 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: (02) 6257 3379 Facsimile: (02) 6257 3420 Email: [email protected] WebSite: www.lwa.gov.au © Land & Water Australia Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication has been published by Land & Water Australia to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the sustainable management of land, water and vegetation. When technical information has been prepared by or contributed by authors external to the Corporation, readers should contact the author(s), and conduct their own enquiries, before making use of that information. Publication data: ‘Principles and Tools for Protecting Australian Rivers’, Phillips, N., Bennett, J. and Moulton, D., Land & Water Australia, 2001. Authors: Phillips, N., Bennett, J. and Moulton, D., Queensland Environmental Protection -

Ship Operations and Activities on the Maroochy River, Final Report to The

Ship operations and activities on the Maroochy River Final Report to the General Manager Final Report to the General Manager, Transport and Main Roads, July 2011 2 of 134 Document control sheet Contact for enquiries and proposed changes If you have any questions regarding this document or if you have a suggestion for improvements, please contact: Contact officer Peter Kleinig Title Area Manager (Sunshine Coast) Phone 07 5477 8425 Version history Version no. Date Changed by Nature of amendment 0.1 03/03/11 Peter Kleinig Initial draft 0.2 09/03/11 Peter Kleinig Minor corrections throughout document 0.3 10/03/11 Peter Kleinig Insert appendices and new maps 0.4 14/03/11 Peter Kleinig Updated recommendations and appendix 1 0.5 13/07/11 Peter Kleinig Updated following meeting 0.6 25/07/11 Peter Kleinig Inserted new maps 1.0 28/07/11 Peter Kleinig Final draft 1.1 28/07/11 Peter Kleinig Final Final Report to the General Manager, Transport and Main Roads, July 2011 3 of 134 Document sign off The following officers have approved this document. Customer Name Captain Richard Johnson Position Regional Harbour Master (Brisbane) Signature Date Reference Group chairperson Name John Kavanagh Position Director (Maritime Services) Signature Date The following persons have endorsed this document. Reference Group members Name Glen Ferguson Position Vice President, Maroochy River Water Ski Association Signature Date Name Graeme Shea Position Representative, Residents of Cook Road, Bli Bli Signature Date Name John Smallwood Position Representative, Sunshine -

Maroochy River Environmental Values and Water Quality Objectives Basin No

Environmental Protection (Water) Policy 2009 Maroochy River environmental values and water quality objectives Basin No. 141 (part), including all tributaries of the Maroochy River July 2010 Prepared by: Water Quality & Ecosystem Health Policy Unit Department of Environment and Resource Management © State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Resource Management) 2010 The Department of Environment and Resource Management authorises the reproduction of textual material, whole or part, in any form, provided appropriate acknowledgement is given. This publication is available in alternative formats (including large print and audiotape) on request. Contact (07) 322 48412 or email <[email protected]> July 2010 Document Ref Number Main parts of this document and what they contain • Scope of waters covered Introduction • Key terms / how to use document (section 1) • Links to WQ plan (map) • Mapping / water type information • Further contact details • Amendment provisions • Source of EVs for this document Environmental Values • Table of EVs by waterway (EVs - section 2) - aquatic ecosystem - human use • Any applicable management goals to support EVs • How to establish WQOs to protect Water Quality Objectives all selected EVs (WQOs - section 3) • WQOs in this document, for - aquatic ecosystem EV - human use EVs • List of plans, reports etc containing Ways to improve management actions relevant to the water quality waterways in this area (section 4) • Definitions of key terms including an Dictionary explanation table of all (section 5) environmental values • An accompanying map that shows Accompanying WQ Plan water types, levels of protection and (map) other information contained in this document iii CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 WATERS TO WHICH THIS DOCUMENT APPLIES ............................................................................. -

The 2053 South Queensland Flood

THE 2053 SOUTH QUEENSLAND FLOOD Only Young Water Professionals Need Attend ABSTRACT A ‘roadshow’ of flood engineers in the early 1980s ‘prophesised’ the flooding that occurred in South East Queensland (SE QLD) during 2011 to 2015. The events of 2011 to 2015 may have given increased credibility to a long-held notion that SE QLD may be subject to a 40-year flood cycle. This paper examines the data on flooding within the ten major SE QLD catchments, bounded by three mountain ranges and comprising more than 63,000 km2. The purpose was to test the existence and the strength of any regularity to flooding in this well-populated region of Australia. The approach identifies the flooding that occurred during predetermined five-year periods that were 35 years apart – the 40-year cycle – and the flooding that occurred outside of these nominated 5-year periods. The basic statistics were weighted for the length of flood record, catchment area, ranking of flood, and a combination of these factors. The results indicate that 69-87% of major floods in SE QLD have occurred within a set of five-year periods exactly 35 years apart. No explanation is offered at this stage of the research. The implications for traditional hydrologic methods are outlined. Keywords: Flooding, flood cycles, regularity, flood frequency INTRODUCTION The early years of the 1970s in South East Queensland was a period of multiple flooding events, remembered mostly for the January 1974 flooding of Brisbane. The following decade was one that experienced widespread estuarine development, where State and Local Government concerns that the development be above the 1in100AEP flood on top of a cyclonic surge, with allowance for future water level rises due to global climatic change, engaged a community of engineers who specialised in relevant fields. -

Flood Risk Management in Australia Building Flood Resilience in a Changing Climate

Flood Risk Management in Australia Building flood resilience in a changing climate December 2020 Flood Risk Management in Australia Building flood resilience in a changing climate Neil Dufty, Molino Stewart Pty Ltd Andrew Dyer, IAG Maryam Golnaraghi (lead investigator of the flood risk management report series and coordinating author), The Geneva Association Flood Risk Management in Australia 1 The Geneva Association The Geneva Association was created in 1973 and is the only global association of insurance companies; our members are insurance and reinsurance Chief Executive Officers (CEOs). Based on rigorous research conducted in collaboration with our members, academic institutions and multilateral organisations, our mission is to identify and investigate key trends that are likely to shape or impact the insurance industry in the future, highlighting what is at stake for the industry; develop recommendations for the industry and for policymakers; provide a platform to our members, policymakers, academics, multilateral and non-governmental organisations to discuss these trends and recommendations; reach out to global opinion leaders and influential organisations to highlight the positive contributions of insurance to better understanding risks and to building resilient and prosperous economies and societies, and thus a more sustainable world. The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics Talstrasse 70, CH-8001 Zurich Email: [email protected] | Tel: +41 44 200 49 00 | Fax: +41 44 200 49 99 Photo credits: Cover page—Markus Gebauer / Shutterstock.com December 2020 Flood Risk Management in Australia © The Geneva Association Published by The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics, Zurich. 2 www.genevaassociation.org Contents 1. -

Predicting and Regulating Boat-Generated Waves Within Rivers and Sheltered Waterways

Predicting And Regulating Boat-generated Waves Within Rivers And Sheltered Waterways Associate Professor Gregor Macfarlane Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY • All marine vessels generate waves. • Vessels now go faster, further and more often. • New issues for other users and the environment: • bank erosion; • damage to moored vessels, jetties and other marine structures; • endanger people working or enjoying activities in small craft or close to the shore. SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY Gordon River, south-west Tasmania SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY Test Sites Boat / Ship Wave Wake Test Sites : • Gordon River, Tasmania • Strahan Harbour, Tasmania • Tamar River, Tasmania • Derwent River, Tasmania • Sydney Harbour (5 locations), Sydney, New South Wales • Parramatta River, Sydney, New South Wales • Hunter River, Newcastle, New South Wales • Brisbane River, Bulimba, Brisbane, Queensland • Brisbane River, upstream of Bremer River, Queensland • Noosa River, Noosa, Brisbane, Queensland • Maroochy River, Maroochydore, Queensland • Swan River, Perth, Western Australia • Canning River, Perth, Western Australia • Daly River, Malak Malak region, Northern Territory • Willamette River, Oregon, United States of America SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY Need to take action… • regulate vessel operations (vessel speed and/or route); • optimise the vessel design; or, • implement remedial measures on shore. SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA | 14 -18 October 2018 MANAGED BY Need to take action…and planning in the early stages • regulate vessel operations (vessel speed and/or route); • optimise the vessel design; or, • implement remedial measures on shore. -

Surface Water Network Review Final Report

Surface Water Network Review Final Report 16 July 2018 This publication has been compiled by Operations Support - Water, Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy. © State of Queensland, 2018 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Interpreter statement: The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding this document, you can contact us within Australia on 13QGOV (13 74 68) and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively communicate the report to you. Surface -

The Crown Lands Alienation Act, 1868"

•11, IN THE WAKE OF THE RAFTSMEN A Survey of Early Settlement in the Maroochy District up to the Passing of "the Crown Lands Alienation Act, 1868" [PART 1] by E. G. HEAP, B.A. (Abridged from the Manuscript in the John Oxley Library) [Ml rights reserved] 1» Early Visitors Neither of the great marine explorers of Australia, James Cook and Matthew Flinders, paid mich attention to the Maroochy District on their voyages along the eastern coast. Cook, after observing the Glasshouse Mountains, commented on "several other peaked hills" to the northward of these. Cook's "low bluff point which was the south point of an open sandy bay" must have been present-day Noosa and Laguna Bay. A belief that he marked the low hills in the Coolum area on his chart as "green hills", (hence the early name for the district), cannot be sus tained. During his voyage in the "Investigator", Flinders did not come close enough to see the Mboloolah and Maroochy estuaries, but remarked on the "ridge of high land topped with small peaKs" which forms part of the western hinterland of the Maroochy District. T3ie first men of European extraction to penetrate the Maroochy District were itinerant ticket-of-leave men and escaped convicts. The district had more than its share of these - two tlcket-of-leave men and five convicts - between 1823 and 1840. The ticket-of-leave men were Paophlett and Parsons, two of the three men located by Oxley's expedition to Moreton Bay, who travelled through the Maroochy District while JouraeylBg to Vide Bay and returning to Stradbroke Island in 1823.