Posthumanism, Subjectivity, Autobiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Posthuman Dimensions of Cyborg: a Study of Man-Machine Hybrid in the Contemporary Scenario

Annals of R.S.C.B., ISSN:1583-6258, Vol. 25, Issue 4, 2021, Pages. 9442 - 9444 Received 05 March 2021; Accepted 01 April 2021. Posthuman Dimensions of Cyborg: A Study of Man-Machine Hybrid in the Contemporary Scenario Annliya Shaijan Postgraduate in English,University of Calicut. ABSTRACT Cyborg theory offers perspectives to analyze the cultural and social meanings of contemporary digital health technologies. Theorizing cyborg called for cultural interrogations. Critics challenged Haraway‟s cyborg and the cyborg theory for not affecting political changes. Cyborg theory is an intriguing approach to analyze the range of arenas such as biotechnology, medical issues and health conditions that incorporate disability, menopause, female reproduction, Prozac, foetal surgery and stem cells.Cyborg is defined by Donna Haraway, in her “A Cyborg Manifesto” (1986), as “a creature in a post-gender world; it has no truck with bisexuality, pre-oedipal symbiosis, unalienated labour, or other seductions to organic wholeness through a final appropriation of all the powers of the parts into a higher unity.” A cyborg or a cybernetic organism is a hybrid of machine and organism. The cyborg theory de-stabilizes from gender politics, traditional notions of feminism, critical race theory, and queer theory and identity studies. The technologies associated with the cyborg theory are complex and diverse. It valorizes the “monstrous, hybrid, disabled, mutated or otherwise „imperfect‟ or „unwhole‟ body.” Scholars have founded it useful and fruitful in the social and cultural analysis of health and medicine. Outline of the Total Work The biomechanics introduces two hybrids of genetic body and cyborg body. The pioneers, Clynes and Kline, in the field to generate man-machine systems, drew ways to new health technologies and their vision of the kind of cyborg has turned to a reality. -

Sapient Circuits and Digitalized Flesh: the Organization As Locus of Technological Posthumanization Second Edition Copyright © 2018 Matthew E

The Organization as Locus of Technological Posthumanization Sapient Circuits and Digitalized Flesh: The Organization as Locus of Technological Posthumanization Second Edition Copyright © 2018 Matthew E. Gladden Published in the United States of America by Defragmenter Media, an imprint of Synthypnion Press LLC Synthypnion Press LLC Indianapolis, IN 46227 http://www.synthypnionpress.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, apart from those fair-use purposes permitted by law. Defragmenter Media http://defragmenter.media ISBN 978-1-944373-21-4 (print edition) ISBN 978-1-944373-22-1 (ebook) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 March 2018 The first edition of this book was published by Defragmenter Media in 2016. Preface ............................................................................................................13 Introduction: The Posthumanized Organization as a Synergism of Human, Synthetic, and Hybrid Agents ........................................................ 17 Part One: A Typology of Posthumanism: A Framework for Differentiating Analytic, Synthetic, Theoretical, and Practical Posthumanisms .............................................................................................31 Part Two: Organizational Posthumanism .................................................... 93 Part Three: The Posthuman Management Matrix: Understanding -

Posthumanism Research Network Two-Day Workshop March 30–31, 2019 SB107 Wilfrid Laurier University Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

‘Posthuman(ist) Alterities’ Posthumanism Research Network two-day workshop March 30–31, 2019 SB107 Wilfrid Laurier University Waterloo, Ontario, Canada We acknowledge the support of the following for making the workshop possible: SSHRC; The Royal Ontario Museum; WLU Faculty of Arts; WLU Office of Research Services; WLU Department of Philosophy; WLU Department of English and Film Studies: WLU Department of Communication Studies ÍÔ Saturday, March 30 9:30 – 11:00 Opening Remarks – SB107 (The Schlegel building, WLU campus) Dr. Russell Kilbourn (English and Film Studies, Wilfrid Laurier University) The conference organizers would like to acknowledge that we are on the traditional territories of the Neutral, Anishnabe, and Haudenosaunee Peoples. Session 1 1. Anna Mirzayan (University of Western): "Things Suck Everywhere: Extractive Capitalism and De-Posthumanism" 2. Christine Daigle (Brock University): “Je est un autre: Collective Material Agency” 3. Sean Braune (Brock University): “Being Always Arrives at its Destination” 11:00 – 11:15 Coffee Break 11:15 – 12:45 Session 2 1. Carly Ciufo (McMaster University): "Of Remembrance and (Human) Rights? Museological Legacies of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in Liverpool" 2. Sascha Priewe (University of Toronto; ROM): “Towards a posthumanist museology” 3. Mitch Goldsmith (Brock University): “Queering our relations with animals: An exploration of multispecies sexuality beyond the laboratory” 12:45 – 2:00 lunch Break veritas café (WLU campus) 2:00 – 3:30 Session 3 1. Matthew Pascucci (Arizona State University): “We Have Never Been Capitalist” 2. Nandita Biswas-Mellamphy (Western University): “Humans ‘Out-of-the-Loop’: AI and the Future of Governance” 3. David Fancy (Brock University): “Vibratory Capital, or: The Future is Already Here” 3:30 – 3:45 Coffee Break 3:45 – 4:45 Session 4 1. -

Climates of Mutation: Posthuman Orientations in Twenty-First Century

Climates of Mutation: Posthuman Orientations in Twenty-First Century Ecological Science Fiction Clare Elisabeth Wall A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in English York University Toronto, Ontario January 2021 © Clare Elisabeth Wall, 2021 ii Abstract Climates of Mutation contributes to the growing body of works focused on climate fiction by exploring the entangled aspects of biopolitics, posthumanism, and eco-assemblage in twenty- first-century science fiction. By tracing out each of those themes, I examine how my contemporary focal texts present a posthuman politics that offers to orient the reader away from a position of anthropocentric privilege and nature-culture divisions towards an ecologically situated understanding of the environment as an assemblage. The thematic chapters of my thesis perform an analysis of Peter Watts’s Rifters Trilogy, Larissa Lai’s Salt Fish Girl, Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl, and Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam Trilogy. Doing so, it investigates how the assemblage relations between people, genetic technologies, and the environment are intersecting in these posthuman works and what new ways of being in the world they challenge readers to imagine. This approach also seeks to highlight how these works reflect a genre response to the increasing anxieties around biogenetics and climate change through a critical posthuman approach that alienates readers from traditional anthropocentric narrative meanings, thus creating a space for an embedded form of ecological and technoscientific awareness. My project makes a case for the benefits of approaching climate fiction through a posthuman perspective to facilitate an environmentally situated understanding. -

Posthumanism – a Critical Analysis

Posthumanism – A Critical Analysis Stefan Herbrechter 1 Contents: Preface 3 Towards a Critical Posthumanism 5 A Genealogy of Posthumanism 38 Our Posthuman Humanity and the Multiplicity of Its Forms 85 Posthumanism and Science Fiction 121 Interdisciplinarity and the Posthumanities 151 Posthumanism, Digitalization and New Media 199 Posthumanity – Subject and System 214 Afterword: The Other Side of Life 227 Bibliography 234 Index (to be provided) 254 2 Preface What is “man”? This age-old question is everywhere today being asked again and with increased urgency, given the current technological developments levering out “our” traditional humanist reflexes. What this development also shows, however, is that the current and intensified attack on the idea of a “human nature” is only the latest phase of a crisis which, in fact, has always existed at the centre of the humanist idea of the human. The present critical study thus produces a genealogy of the contemporary posthumanist scenario of the “end of man” and places it within the context of theoretical and philosophical developments and ways of thinking within modernity. Even though terms like “posthuman”, “posthumanist” or “posthumanism” have a surprisingly long history they have only really started to receive attention in contemporary theory and philosophy in the last two decades where they have produced an entire new way of thinking and theorizing. Only in the last ten years or so, posthumanism has established itself – mainly in the Anglo-American sphere – as an autonomous field of study with its own theoretical approach (especially within the so-called “theoretical humanities”). The first academic publications that deal systematically with the idea of the posthuman and posthumanism appeared at the end of the 1990s and the early 2000s (these are, in particular, works by N. -

A Typology of Posthumanism

Part One Abstract. The term ‘posthumanism’ has been employed to describe a diverse array of phenomena ranging from academic disciplines and artistic move- ments to political advocacy campaigns and the development of commercial technologies. Such phenomena differ widely in their subject matter, purpose, and methodology, raising the question of whether it is possible to fashion a coherent definition of posthumanism that encompasses all phenomena thus labelled. In this text, we seek to bring greater clarity to this discussion by formulating a novel conceptual framework for classifying existing and poten- tial forms of posthumanism. The framework asserts that a given form of posthumanism can be classified: 1) either as an analytic posthumanism that understands ‘posthumanity’ as a sociotechnological reality that already exists in the contemporary world or as a synthetic posthumanism that understands ‘posthumanity’ as a collection of hypothetical future entities whose develop- ment can be intentionally realized or prevented; and 2) either as a theoretical posthumanism that primarily seeks to develop new knowledge or as a practi- cal posthumanism that seeks to bring about some social, political, economic, or technological change. By arranging these two characteristics as orthogonal axes, we obtain a matrix that categorizes a form of posthumanism into one of four quadrants or as a hybrid posthumanism spanning all quadrants. It is suggested that the five resulting types can be understood roughly as posthu- manisms of critique, imagination, conversion, -

The Echo Maker Zachary Tavlin

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 2 | 2016 Ordinary Chronicles of the End of the World Chroniques ordinaires de la fin du monde Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/8278 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.8278 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher AFEA Electronic reference Transatlantica, 2 | 2016, “Ordinary Chronicles of the End of the World” [Online], Online since 31 December 2016, connection on 29 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/ 8278; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.8278 This text was automatically generated on 29 April 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chroniques ordinaires de la fin du monde Introduction. Chronicles of the End of the World: The End is not the End Arnaud Schmitt The Ubiquity of Strange Frontiers: Minor Eschatology in Richard Powers’s The Echo Maker Zachary Tavlin Writing (at) the End: Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge Brian Chappell Apocalypse and Sensibility: The Role of Sympathy in Jeff Lemire’s Sweet Tooth André Cabral de Almeida Cardoso The Double Death of Humanity in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road Stephen Joyce « A single gray flake, like the last host of christendom » : The Road ou l’apocalypse selon St McCarthy Yves Davo Hors Thème L’usure iconique. Circulation et valeur des images dans le cinéma américain contemporain Mathias Kusnierz Actualité de la recherche Civilisation Colloque « Corps en politique » Université Paris-Est Créteil, 7-9 septembre 2016 Lyais Ben Youssef Colloque « Conflit, Pouvoir et Représentations » Université du Maine, 18 et 19 novembre 2016 Clément Grouzard One-day symposium “Mapping the landscapes of abortion, birth control and power in the United States since the 1960s”. -

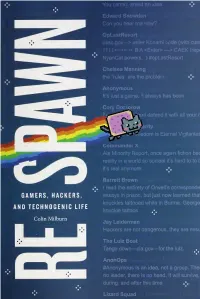

Respawn: Gamers, Hackers, and Technogenic Life

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Duke University Libraries https://archive.org/details/respawngamershacOOmilb EXPERIMENTAL FUTURES Technological lives, scientific arts, anthropological voices A series edited by Michael M. J. Fischer and Joseph Dumit GAMERS, HACKERS, AND TECHNOGENIC LIFE Colin Milburn © 2018 DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS This title is freely available in All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America an open access edition thanks to the tome initiative and on acid-free paper «=. Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker the generous support of the and typeset in Minion Pro and Knockout by Westchester University of California, Davis. Publishing Services. Learn more at openmono graphs.org. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data This book is published Names: Milburn, Colin, [date] author. under the Creative Commons Title: Respawn : gamers, hackers, and technogenic life / Attribution-NonCommercial- Colin Milburn. NoDerivs 3.0 United States Description: Durham: Duke University Press, 2018. | (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 US) Series: Experimental futures : technological lives, License, available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses scientific arts, anthropological voices | /by-nc-nd/3.o/us/. Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018019514 (print) Cover art: Nyan Cat. lccn 2018026364 (ebook) © Christopher Torres. isbn 9781478002789 (ebook) www.nyan.cat. ISBN 9781478001348 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478002925 (pbk.: alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Video games. | Hackers. | Technology—Social aspects. Classification: LCC Gv1469.34.s52 (ebook) | lcc Gv1469.34.s52 M55 2018 (print) | ddc 794.8—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019514 CONTENTS Introduction. All Your Base 1 1 May the Lulz Be with You 25 2 Obstinate Systems 51 3 Still Inside 78 4 Long Live Play 102 5 We Are Heroes 134 6 Green Machine 172 7 Pwn 199 Conclusion. -

Posthumanist Education

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CURVE/open Posthumanist Education Stefan Herbrechter Accepted manuscript PDF deposited in Coventry University’s Repository Original citation: ‘Posthumanist Education’, in International Handbook of Philosophy of Education, ed. by Paul Smeyers, pub 2018 (ISBN 9783319727592) Publisher: Springer Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Stefan Herbrechter Posthumanist education Abstract: This contribution distinguishes between different varieties of posthumanism. It promotes a ‘critical posthumanism’ which engages with an emerging new world picture at the level of ethics, ecology, politics, technology and epistemology. On this basis, the contribution explores the question of a posthumanist and postanthropocentric education both from a philosophical, theoretical and practical, curricular point of view. It concludes by highlighting some of the implications that a posthumanist education might have. Keywords: Critical posthumanism, ecology, postanthropocentrism, animal studies, new literacies 1. The posthumanisation of the education system One might be very tempted to dismiss the subject posthumanism merely as another Anglo-American theory fashion and to simply wait for this latest ‘postism’ to go the way of all previous ones. If there was no globalization with its tangible effects both at an economic as well as media and cultural level, this might indeed be possible or even a sensible thing to do. -

Recent Approaches in the Posthuman Turn: Braidotti, Herbrechter, And

Recent Approaches in the Posthuman Turn Braidotti, Herbrechter, and Nayar Bas¸ak Ag˘ın Dönmez PhD and Instructor (English), Middle East Technical University, Ankara [email protected] Braidotti, Rosi. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press. 180 pp. $ 19.95. ISBN 978-0-7456-4158-4 Herbrechter, Stefan. 2013. Posthumanism: a Critical Analysis. London: Bloomsbury. 248 pp. $ 29.95. ISBN 978-1-78093-606-2 Nayar, Pramod K. 2014. Posthumanism. Cambridge: Polity Press. 204 pp. $ 24.95. ISBN 978-0-7456-6241-1 The posthuman turn in its current phase owes much to the new material- ist paradigm, which has mainly extended the definition of agency to the nonhuman sphere. Such extension has led to significant boundary break- downs between the biotic and the abiotic, nature and culture, as well as discourse and matter. The privileged status of information over materiality had long overshadowed posthumanism from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, when biotechnological developments triggered the idealization of super-human fantasies with complete disregard for the rest of the planetary inhabitants. The conflict between “the old” and “the new” approaches to posthumanism recalls Katherine Hayles’s famous words. On the one hand, posthumanism is misunderstood and associated with a form of incorporeal cognizance, as in Hans Moravec’s naïve fantasies of doing away with the bodily capabilities of the human altogether in Mind Children (1988). On the other hand, posthumanism incorporates both the material and the dis- cursive into a form of embodied consciousness: -

Who Will Be the Members of Society 5.0? Towards an Anthropology of Technologically Posthumanized Future Societies

Article Who Will Be the Members of Society 5.0? Towards an Anthropology of Technologically Posthumanized Future Societies Matthew E. Gladden LAIBS, Anglia Ruskin University, East Road, Cambridge CB1 1PT, UK; [email protected]; Tel.: +48-668-968-054 Received: 31 March 2019; Accepted: 7 May 2019; Published: 10 May 2019 Abstract: The Government of Japan’s “Society 5.0” initiative aims to create a cyber-physical society in which (among other things) citizens’ daily lives will be enhanced through increasingly close collaboration with artificially intelligent systems. However, an apparent paradox lies at the heart of efforts to create a more “human-centered” society in which human beings will live alongside a proliferating array of increasingly autonomous social robots and embodied AI. This study seeks to investigate the presumed human-centeredness of Society 5.0 by comparing its makeup with that of earlier societies. By distinguishing “technological” and “non-technological” processes of posthumanization and applying a phenomenological anthropological model, this study demonstrates: (1) how the diverse types of human and non-human members expected to participate in Society 5.0 differ qualitatively from one another; (2) how the dynamics that will shape the membership of Society 5.0 can be conceptualized; and (3) how the anticipated membership of Society 5.0 differs from that of Societies 1.0 through 4.0. This study describes six categories of prospective human and non-human members of Society 5.0 and shows that all six have analogues in earlier societies, which suggests that social scientific analysis of past societies may shed unexpected light on the nature of Society 5.0. -

Technology, Media Literacy, and the Human Subject: a Posthuman Approach (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2021)

Technology, Media Literacy, and the Human Subject R.S. L A Posthuman Approach EWIS RICHARD S. LEWIS Media literacy is oft en focused on evaluati ng the message rather than refl ecti ng on the medium. Technology, Media Literacy, and the Human Subject and Media Literacy, Technology, Bringing together postphenomenology, media ecology, posthumanism, and complexity theory, Richard Lewis off ers a method for such a refl ecti on and shows how our everyday media environments consti tute us as (post)human subjects, always in a state of becoming. An original interdisciplinary eff ort and a must-read for everyone interested in how we become with and through technologies. Prof. Mark Coeckelbergh, University of Vienna We are mediated by and immersed in a world where informa� on and communica� on technologies (ICTs) are undergoing accelerated innova� on. From hardware like smartphones, smartwatches, and home assistants to so� ware like Facebook, Instagram, Twi� er, and Snapchat, our lives have become inextricably entwined with a complex, interconnected network of rela� ons. Scholarship on media literacy has tended to focus on developing the skills to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media messages without considering or weighing the impact of the technological medium and the broader context. What does it mean to be media literate in today’s world? How are we transformed by the many media infrastructures around us? These issues are addressed through the crea� on of a transdisciplinary approach that allows for both prac� cal and theore� cal analyses of media inves� ga� ons. The author proposes a framework and a pragma� c instrument for understanding the mul� plicity of rela� ons that all contribute to how we aff ect—and are aff ected by—our rela� ons with media technology.