India Continuing Repression in Kashmir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Journal of Hill Farming Socio-Economic Profile of Sheep Rearing Community in Bandipora District of Jammu and Kashmir

Content list available at http://epubs.icar.org.in, www.kiran.nic.in; ISSN: 0970-6429 Indian Journal of Hill Farming December 2017, Volume 30, Issue 2, Page 307-312 Socio-Economic Profile of Sheep Rearing Community in Bandipora District of Jammu and Kashmir Anees Ahmad Shah1*. Hilal Musadiq Khan1 . Parwaiz Ahmad Dar1 . Masood Saleem Mir2 1Division of Livestock Production & Management, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences & Technology Kashmir-190006, Jammu & Kashmir 2Division of Veterinary Pathology, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences & Technology Kashmir-190006, Jammu & Kashmir ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: A survey was conducted to study the socio-economic condition of sheep rearing Received 17 November 2016 community in Bandipora district of Kashmir. The district was divided into low-lying Revision Received 23 May 2017 Accepted 6 July 2017 (Sonawari), medium altitude (Bandipora) and High altitude (Gurez) regions. Multi-stage ----------------------------------------------- random sampling was done in which 20% villages were selected from each region in the Key words: Sheep, Bandipora, socio-economic, first stage through proportionate random sampling and 20 respondents from each selected profile village in second stage through simple random sampling. A total of 480 respondents ---------------------------------------------- (Sonawari=200, Bandipora=160, Gurez=120) from 24 villages were considered for the survey. It was observed that majority of the sheep rearers (59.79%) were illiterate with proportion of such respondents being significantly higher (p<0.05) in Gurez (68.33%) than Sonawari (54.0%) region. Majority (65.8%) of sheep rearers in the district were having medium size families (5-8 members) with an average family size of 6.60±0.129 with majority (86.7%) of the families being nuclear type. -

2019 HSSP Scholars S.NO

2019 HSSP Scholars S.NO. NAME OF THE SCHOLAR FATHER'S /GUARDIAN NAME GENDER ADDRESS DISTRICT PIN CODE 1 Aabid Khazir Khazir Mohd Dar Male Rathsun Beerwah Budgam Budgam 193401 2 Aabiroo Fayaz Fayaz Ahmad Male Krangsoo Mattan Anantnag 192125 3 Aafreena Farooq Farooq Ahmad Female Dangerpora Budgam 191111 4 Aaliya Akbar Mohd Akbar Rather Female Aarath Pethpora Budgam 191111 5 Aamina Nazir Nazir Ahmad Naik Female Bhan Qaimah Kulgam Kulgam 192231 6 Aanis Yaqoob Mohammad Yaqoob Dass Male Akingam Kokernag Anantnag 192201 7 Aarif Hussain Shaksaz Nisaar Ahmad Shaksaz Male Bidder Kokernag Anantnag 912202 8 Aayat Nazir Nazir Ahmad Bhat Female Syed Karim Old Town Baramulla 193101 9 Abid Mushtaq Mushtaq Ahmad Malik Male Urwan Newa Pulwama 192301 10 Afreen Showkat Showkat Ahmad Roshangar Female Wantapora Srinagar 190002 11 Afreena Hassan Gh Hassan War Female Manigam Lar Ganderbal 191201 12 Amjad Hussain Malik Mohd Jaffar Malik Male Goom Ahmadpora Pattan Baramulla 193401 13 Aneesa Rehman Ab.Rehman Bhat Female Panzan Chadoora Budgam 191113 14 Anum Malik Tabasum Javid Ahmad Female Konibal Pampore Pulwama 192121 15 Aqsa Reyaz Wani Reyaz Ah Wani Female Khudwani Nai Basti Kulgam 192231 16 Arbeena bashir Bashir Ahmad Bhat Female Urpash Ganderbal 191201 17 Arbeena Rayees Late Rayees Ahmad Hajam Female Qadeem Masjid Lane Lal Bazar Srinagar 190023 18 Armeena Reyaz Reyaz Ahmad Sheikh Female Makand Pora Kulgam 192231 19 Arsalan Maqbool Mohd Maqbool Bhat Male Arwani Near Govt School Nai Basti Anantnag `192124 20 Arshiqa Showkat Showkat Ahmad Khan Female Old Nishat Srinagar 191121 21 Arzeena Showkat Showkat Ah Wani Female Khudwani Qanimoh Kulgam 192102 22 Asiya Rashid Abdul Rashid Khan Female Gundi Darwesh Hariwani Khansahib Budgam 191111 23 Asmat Bashir Bashir Ah. -

Kashmir Council-Eu Kashmir Council-Eu

A 004144 02.07.2020 KASHMIR COUNCIL-EU KASHMIR COUNCIL-EU Mr. David Maria SASSOLI European Parliament Bât.PAUL-HENRI SPAAK 09B011 60, rue Wiertz B-1047 Bruxelles June 1, 2020 Dear President David Maria SASSOLI, I am writing to you to draw your attention to the latest report released by the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition on Civil Society (JKCCS) and Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) which documents a very dire human rights situation in Indian-Administered Kashmir, due to the general breakdown of the rule of law. The report shows that at least 229 people were killed following different incidents of violence, including 32 civilians who lost their life due to extrajudicial executions, only within a six months period, from January 1, 2020, until 30 June 2020. Women and children who should be protected and kept safe, suffer the hardest from the effects of the conflict, three children and two women have been killed over this period alone. On an almost daily basis, unlawful killings of one or two individuals are reported in Jammu and Kashmir. As you may be aware, impunity for human rights abuses is a long-standing issue in Jammu and Kashmir. Abuses by security force personnel, including unlawful killings, rape, and disappearances, have often go ne uninvestigated and unpunished. India authorities in Jammu and Kashmir also frequently violate other rights. Prolonged curfews restrict people’s movement, mobile and internet service shutdowns curb free expression, and protestors often face excessive force and the use of abusive weapons such as pellet-firing shotguns. While the region seemed to have slowly emerging out of the complete crackdown imposed on 5 August 2019, with the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the lockdown was reimposed and so the conditions for civilians remain dire. -

Revised Status of Eligibility for the Post

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR Revised Status of Eligibility Post: Medical Officer -02-UR (01-Male, 01-Female) Employment Notification No. 01 of 2018 Date: 07-02-201 Employment Notification No. 15 of 2015 Dated 07-10-2015 Employment Notification No. 08 of 2014 Dated 08-08-2014 S.No. Name of the Applicant Category Status of Eligibility 1 Dr Mansoora Akhter UR Not Eligible D/o Gh Mohd Wani Experience in Gynecology & Obstetrics less than R/o Akingam Bonpora,Kokernag Anantnag- required 192201 2 Dr Amara Gulzar UR S/o Gulzar Mohamad Eligible R/o Hari Pari Gam Awantipora Pulwama- 192123 3 DrCell:7780867318 Farukh Jabeen UR D/o Masoud-Ur-Raheem Eligible C/o Mustafa Aabad Sector-I,Near Mughal Darbar,Lane-D,Zainakote Srinagar-190012 4 DrCell:9622457524 Sadaf Shoukat UR D/o Shoukat Ali Khan Eligible C/o H.N-193198 Cell:9906804176/9797954129 5 [email protected] Saba Sharief Dewani UR R/o Sector B,H.N-9,Jeelanabad Peerbagh Eligible Hyderpora-190014 6 [email protected] Aaliya UR Not Eligible S/o Ghulam Mohiud Din Wani No Experience in Gyne & Obstetrics R/o H.N-C11,Milatabad Peerbgh,new Airport road-190014 7 DrCell:9419553888 Safeena Mushtaq UR D/o Mushtaq Ahmad Dar Not Eligible R/o Shahi Mohalla Awanta Bhawan Ashiana Habibi,Soura Srinagar-9596183219 8 Dr Berjis Ahmad UR D/o Gh Ahmad Ahanger Not Eligible R/o 65,Pamposh Colony,Lane-9,Natipora no experience in Gyne & Obst. Srinagar-190015 9 DrCell:2430726 Naira Taban UR D/o M.M.Maqbool Not Eligible R/o H.N-223,Nursing Garh Balgarden- no experience in Gyne & Obstetrics. -

DC Valuation Table (2018-19)

VALUATION TABLE URBAN WAGHA TOWN Residential 2018-19 Commercial 2018-19 # AREA Constructed Constructed Open Plot Open Plot property per property per Per Marla Per Marla sqft sqft ATTOKI AWAN, Bismillah , Al Raheem 1 Garden , Al Ahmed Garden etc (All 275,000 880 375,000 1,430 Residential) BAGHBANPURA (ALL TOWN / 2 375,000 880 700,000 1,430 SOCITIES) BAGRIAN SYEDAN (ALL TOWN / 3 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 SOCITIES) CHAK RAMPURA (Garision Garden, 4 275,000 880 400,000 1,430 Rehmat Town etc) (All Residential) CHAK DHEERA (ALL TOWN / 5 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIETIES) DAROGHAWALA CHOWK TO RING 6 500,000 880 750,000 1,430 ROAD MEHMOOD BOOTI 7 DAVI PURA (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) 275,000 880 350,000 1,430 FATEH JANG SINGH WALA (ALL TOWN 8 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) GOBIND PURA (ALL TOWNS / 9 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIEITIES) HANDU, Al Raheem, Masha Allah, 10 Gulshen Dawood,Al Ahmed Garden (ALL 250,000 880 350,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) JALLO, Al Hafeez, IBL Homes, Palm 11 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 Villas, Aziz Garden etc KHEERA, Aziz Garden, Canal Forts, Al 12 Hafeez Garden, Palm Villas (ALL TOWN 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) KOT DUNI CHAND Al Karim Garden, 13 Malik Nazir G Garden, Ghous Garden 250,000 880 400,000 1,430 (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) KOTLI GHASI Hanif Park, Garision Garden, Gulshen e Haider, Moeez Town & 14 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 New Bilal Gung H Scheme (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Al Wadood Garden (ALL 15 225,000 880 500,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Ring Road Par (ALL TOWN 16 75,000 880 200,000 -

The Occupied Clinic Militarism and Care in Kashmir / Saiba Varma the OCCUPIED CLINIC the Occupied Clinic

The Occupied Clinic Militarism and Care in Kashmir / Saiba Varma THE OCCUPIED CLINIC The Occupied Clinic Militarism and Care in Kashmir • SAIBA VARMA DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS DURHAM AND LONDON 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Text design by Amy Ruth Buchanan Cover design by Courtney Leigh Richardson Typeset in Portrait by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Varma, Saiba, [date] author. Title: The occupied clinic : militarism and care in Kashmir / Saiba Varma. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019058232 (print) | lccn 2019058233 (ebook) isbn 9781478009924 (hardcover) isbn 9781478010982 (paperback) isbn 9781478012511 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Psychiatric clinics—India—Jammu and Kashmir. | War victims—Mental health—India—Jammu and Kashmir. | War victims—Mental health services— India—Jammu and Kashmir. | Civil-military relations— India—Jammu and Kashmir. | Military occupation— Psychological aspects. Classification:lcc rc451.i42 j36 2020 (print) | lcc rc451.i42 (ebook) | ddc 362.2/109546—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019058232 isbn ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019058233 Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the Office of Vice Chancellor for Research at the University of California, San Diego, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. Cover art: Untitled, from The Depth of a Scar series. © Faisal Magray. Courtesy of the artist. For Nani, who always knew how to put the world back together CONTENTS MAP viii NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi LETTER TO NO ONE xv INTRODUCTION. Care 1 CHAPTER 1. -

National Creche Scheme State/UT: Jammu & Kashmir

National Creche Scheme State/UT: Jammu & Kashmir S. No: Name of Creche Address District 1 Goripora/ Ganderbal Ganderbal Gundander 2 Arche Arch, Ganderbal Ganderbal 3 Bakshi Pora Bakshirpora Srinagar Noor bagh 4 Takunwari Takunwar, Near Ganderbal Panchyat 5 Kachan Kachan Near Masjid Ganderbal 6 Prang Prang, Near Jamia Masjid Ganderbal 7 Goripora Goripora, Noor Srinagar Baghnear, Watertant 8 Saida kadal Saida Kadal, Makdoom Srinagar Mohalla 9 Saida kadal Saida Kadal, Near Imam Srinagar Bada 10 Chuntwaliwar Chuntwaliwar Ganderbal 11 Peerpora Peerpora, Near Masjid Ganderbal 12 Daribal Daribal, Near Masjid Ganderbal 13 Auntbawan Auntbawa Srinagar 14 Gangerhama Gangarhama, Near Govt. Ganderbal School 15 Shalibugh Shalibugh, Pathkundalnear Ganderbal Govt. School 16 Galdarpora Galdarpora, Near Masjid Ganderbal 17 Sendibal Sendibal, Near Masjid Ganderbal 18 Hakleemgund Hakeemgund, Kachan near Ganderbal Masjid 19 Shamaspora Lar,Gganderbal Ganderbal 20 Benehama Lar, Ganderbal Ganderbal 21 Baroosa Ganderbal Ganderbal 22 Abi Karpora Abi Karpora, Srinagar Srinagar 23 Mir Mohalla Negoo, Branwar Budgam Negoo 25 Chandkote, Baramuilla Baramulla 26 Gulshanpura, Tral Tral 27 Kreeri, Baramulla Baramulla 28 Nowshera, Srinagar Srinagar 29 Hutmurah Near Jamia Masjid, Anantnag Hutmurah, Anantnag 30 Banderpora Near Water pump Pulwama Banderpora, Pulwama 31 BK Pora Near Govt. High School BK Budgam Pura, Badgam 32 Janipur H.No. 14, Shiv Vikas Janipur, Jammu opp. Higher Sec. School, 33 Preet Nagar H.No. 54, Preet Nagar Jammu Deva Palace, Jammu 34 Safa Kadal Safa Kadal, Dareshkadal Srinagar Srinagar 35 Bemina MIG Colony, Zubir Masjid, Srinagar Srinagar 36 Nehru Park Kand Mohalla, Dalgate Srinagar Nehru Park, Srinagar 37 Chakmange Near Glader Mandir, Border Samba Area, Samba 38 Sidco, Samba Sidco Samba Samba 39 Manda Rajouri Road. -

CJ Kashmir [Annexure List of Students Selected for Free Coaching Under 10% Reserved Departmental Quota

Government of Jam mu & Kashmir DI RECTO RA TE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION AS H MIR Subject:- List of Candidate for Pri, ak Coaching/Tuition Centres under 10% Reserved Departmental Quota for the session 2019-20 under different catagories. Pursuant to the Govt. Order No: 435-Edu of 2010 elated: 30-04-20 10, a list of 4439 candidates is forwarded to the Private Coaching/Tuition Centres under I 0% Reserved Departmental quota for the session 201 9-20 The following conditions shall be implemented in letter & spirit:• I. The concerned Private Coaching/Tuition Centres are advised to check the authenticity of the relevant Category on which benefit is claimed with the original documents before the selected candidate is allowed to join for free coaching under I0% departmental reserved quota in lieu of Govt. order referred above. 2. The concerned Private Coaching/Tuition Centres shall not allow the selected candidate, in case of any variation in the particulars of the selected candidates reflected in the order especially the categ<H:J' under which selected and shall be conveyed the same to this office within one week. 3. That the Selected candidates having any grievance shall approach this office within JO days positively, 4. That tire concerned Private Coaching/Tuition Centres shall submit tire detailed report to this office within one week about the joining of candidate. Sci/- Director School Education Kashmir Nu: DSEK/GS/10%/quota/862/2020 Dated: 08-01-2020 Copy to the:• ()1. Divisional Commissioner, Kashmir for information. 02. Commissioner/Secretary to Government. School Education Department Civil Secretariat, .la11111111 for information. -

District Census Handbook, Srinagar, Parts X-A & B, Series-8

CENSUS 1971 PARTS X-A & B TOWN & VILLAGE DIRECTORY SERIES-8 JAMMU & KASHMIR VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS .. ABSTRACT SRINAGAR DISTRICT DISTRICT 9ENSUS . ~')y'HANDBOOK J. N. ZUTSHI of the Kashmir Administrative Service Director of Census Operations Jammu and Kashmir '0 o · x- ,.,.. II ~ ) "0 ... ' "" " ._.;.. " Q .pi' " "" ."" j r) '" .~ ~ '!!! . ~ \ ~ '"i '0 , III ..... oo· III..... :I: a:: ,U ~ « Z IIJ IIJ t9 a: « Cl \,.. LL z_ UI ......) . o ) I- 0:: A..) • I/) tJ) '-..~ JJ CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Central Government Publications-Census of India 1971-Series 8-Jammu & Kashmir is being Published in the following parts. Number Subject Covered Part I-A General Report Part I-B General Report Part I-C Subsidiary Tables Part II-A General Population Tables Part JI-B Economic Tables Part II-C(i) Population by Mother Tongue, Religion, Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. Part II-C(ii) Social & Cultural Tables and Fertility Tables Part III Establishments Report & Tables Part IV Housing Report and Tables Part VI-A Town Directory Part VI-B Special Survey Reports on Selected Towns Part VI-C Survey Reports on Selected Villages Part VIII-A Administration Report on Enumeration Part VIII-B Administration Report on Tabulation Part IX Census Atlas Part IX-A Administrative Atlas Miscellaneous ei) Study of Gujjars & Bakerwals (ii) Srinagar City DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOKS Part X-A Town & Village Directory Part X-B Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract Part X-C Analytical Report, Administrative Statistics & District Census Table!! -

Dead but Not Forgotten

DEAD BUT NOT FORGOTTEN Survey on people killed since 1989-2006 in Baramulla District, of Jammu Kashmir Conducted by JAMMU KASHMIR COALITION OF CIVIL SOCIETY The Bund, Amira Kadal, Srinagar Jammu Kashmir 190001 Tel: +91-194-2482820 Email: [email protected] Web: www.jkccs.org Acknowledgements Studies and surveys undertaken as a collective work and based on voluntary participation of people, where only travel expenses can be met, are an exhilarating experience for the participants. But it is time consuming, and harmonizing pre-occupations of working for living with availability of time for voluntary work can be confounding. There were also moments of tension and frustration because the work was taking too long to complete. But successful teamwork, once completed, is its own reward. The enthusiasm of team members and the process of learning inherent in such efforts is the reason why it is so. This survey and our analysis are now in the public domain. We welcome criticism that will help us improve standard of our work and plug shortcomings that may be brought to our notice. Because struggle for freedom for us also means a commitment to rigorously de-mystify obfuscatory politics, based on a denial of the essential truth that the struggle of our people is just and democratic. A struggle that is getting besmirched by the politics of slander and surrender. We acknowledge our gratitude to the people of Baramulla who so readily came forward to talk to us. And who wanted to share so much more, which, given the nature of the survey, we could not honour. -

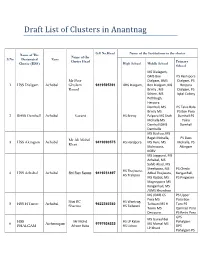

Draft List of Clusters in Anantnag

Draft List of Clusters in Anantnag Name of The Cell No.Head Name of the Institutions in the cluster Name of the S.No Designated Zone Cluster Head Primary Cluster (HSS) High School Middle School School MS Dialagam, GMS Bon PS Reshipora Mr Peer Dialgam, BMS Dialgam, PS 1 HSS Dialgam Achabal Ghulam 9419595391 GHS Dialgam, Bon Dialgam, MS Herpora Rasool Brinty , MS Dialgam, PS Schien, MS Iqbal Colony Pethbugh, Herpora Damhall, MS PS Takia Bala Brinty MS PS Bon Pora 2 BHSS Damhall Achabal Vacant HS Brinty Palpora MS Shah Damhall PS Mohalla MS Takia Damhall GMS Damhall Damhalla MS Budroo, MS Bagat Mohalla, PS Dass Mr Ali Mohd 3 HSS Akingam Achabal 9419090575 HS Hardpora MS Reni, MS Mohalla, PS Khan Mohripora, Akingam KGBV MS Jogigund, MS Achabal, MS Sahib Abad, MS Sheelipora, MS PS Checki HS Thajiwara, 4 HSS Achabal Achabal Shri Ram Saroop 9419231897 Adbal Thajiwara, Kanganhall, HS Trahpoo MS Razbal, MS PS Pingwani Magreypora MS Kanganhall, MS /GMS Khundroo MS /GMS CS PS Upper Pora MS Pora Bon Shri RC HS Wantrag, 5 HSS H Turoo Achabal 9622360360 Tailwani MS H Turu PS Sharma HS Tailwani Tooru MS Qamrazi Pora Devipora PS Reshi Pora GPS MS Ganeshbal HSS Mr Mohd HS LP Kalan Pahalgam 6 Aishmuqam 9797924525 MS Mamal MS PHALGAM Afrooz Baba HS Lidroo DPS LP Khurd Pahalgam PS Ganeshbal PS Rangward MS Ainoo MS BHS Jammu MS GHSS Shri Ashwani 7 Aishmuqam 9419135890 Aishmuqam Latroo MS Peer PS Tulhard AISHMUQAM Kumar HS Logripora Mohalla GMS /MS Aishmuqam MS Naibasti MS Pushwara MS Hanjidanter KGBV Hanjidanter MS Mirdanter MS Mtr GHS Khanabal GIRLS HSS -

District Budgam - a Profile

DISTRICT BUDGAM - A PROFILE Budgam is one of the youngest districts of J&K, carved out as it was from the erstwhile District Srinagar in 1979. Situated at an average height of 5,281 feet above sea-level and at the 34°00´.54´´ N. Latitude and 74°.43´11´´ E. Longitude., the district was known as Deedmarbag in ancient times. The topography of the district is mixed with both mountainous and plain areas. The climate is of the temperate type with the upper-reaches receiving heavy snowfall in winter. The average annual rainfall of the district is 585 mm. While the southern and south-western parts are mostly hilly, the eastern and northern parts of the district are plain. The average height of the mountains is 1,610 m and the total area under forest cover is 477 sq. km. The soil is loose and mostly denuded karewas dot the landscape. Comprising Three Sub-Divisions - Beerwah, Chadoora and Khansahib; Nine Tehsils - Budgam, Beerwah, B.K.Pora, Chadoora, Charisharief, Khag, Khansahib, Magam and Narbal; the district has been divided into seventeen blocks namely Beerwah, Budgam, B.K.Pora, Chadoora, ChrariSharief, Khag, Khansahib, Nagam, Narbal, Pakherpoa, Parnewa, Rathsun, Soibugh, Sukhnag, Surasyar, S.K.Pora and Waterhail which serve as prime units of economic development. Budgam has been further sliced into 281 panchayats comprising 504 revenue villages. AREA AND LOCATION Asset Figure Altitude from sea level 1610 Mtrs. Total Geographical Area 1361 Sq. Kms. Gross Irrigated Area 40550 hects Total Area Sown 58318 hects Forest Area 477 Sq. Kms. Population 7.53 lacs (2011 census) ADMINISTRATIVE SETUP Sub.