Resonances in the British Invasion, 1965-1968 Jonathan D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Chris Billam-Smith

MEET THE TEAM George McMillan Editor-in-Chief [email protected] Remembrance day this year marks 100 years since the end of World War One, it is a time when we remember those who have given their lives fighting in the armed forces. Our features section in this edition has a great piece on everything you need to know about the day and how to pay your respects. Elsewhere in the magazine you can find interviews with The Undateables star Daniel Wakeford, noughties legend Basshunter and local boxer Chris Billam Smith who is now prepping for his Commonwealth title fight. Have a spooky Halloween and we’ll see you at Christmas for the next edition of Nerve Magazine! Ryan Evans Aakash Bhatia Zlatna Nedev Design & Deputy Editor Features Editor Fashion & Lifestyle Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Silva Chege Claire Boad Jonathan Nagioff Debates Editor Entertainment Editor Sports Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3 ISSUE 2 | OCTOBER 2018 | HALLOWEEN EDITION FEATURES 6 @nervemagazinebu Remembrance Day: 100 years 7 A whitewashed Hollywood 10 CONTENTS /Nerve Now My personal experience as an art model 13 CONTRIBUTORS FEATURES FASHION & LIFESTYLE 18 Danielle Werner Top tips for stress-free skin 19 Aakash Bhatia Paris Fashion Week 20 World’s most boring Halloween costumes 22 FASHION & LIFESTYLE Best fake tanning products 24 Clare Stephenson Gracie Leader DEBATES 26 Stephanie Lambert Zlatna Nedev Black culture in UK music 27 DESIGN Do we need a second Brexit vote? 30 DEBATES Ryan Evans Latin America refugee crisis 34 Ella Smith George McMillan Hannah Craven Jake Carter TWEETS FROM THE STREETS 36 Silva Chege James Harris ENTERTAINMENT 40 ENTERTAINMENT 7 Emma Reynolds The Daniel Wakeford Experience 41 George McMillan REMEMBERING 100 YEARS Basshunter: No. -

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Course Outline and Syllabus the Fab Four and the Stones: How America Surrendered to the Advance Guard of the British Invasion

Course Outline and Syllabus The Fab Four and the Stones: How America surrendered to the advance guard of the British Invasion. This six-week course takes a closer look at the music that inspired these bands, their roots-based influences, and their output of inspired work that was created in the 1960’s. Topics include: The early days, 1960-62: London, Liverpool and Hamburg: Importing rhythm and blues and rockabilly from the States…real rock and roll bands—what a concept! Watch out, world! The heady days of 1963: Don’t look now, but these guys just might be more than great cover bands…and they are becoming very popular…Beatlemania takes off. We can write songs; 1964: the rock and roll band as a creative force. John and Paul, their yin and yang-like personal and musical differences fueling their creative tension, discover that two heads are better than one. The Stones, meanwhile, keep cranking out covers, and plot their conquest of America, one riff at a time. The middle periods, 1965-66: For the boys from Liverpool, waves of brilliant albums that will last forever—every cut a memorable, sing-along winner. While for the Londoners, an artistic breakthrough with their first all--original record. Mick and Keith’s tempestuous relationship pushes away band founder Brian Jones; the Stones are established as a force in the music world. Prisoners of their own success, 1967-68: How their popularity drove them to great heights—and lowered them to awful depths. It’s a long way from three chords and a cloud of dust. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

The Inner Light: the Beatles, India, Gurus, and the Legacy

The Inner Light: The Beatles, India, Gurus, and the Legacy John Covach Institute for Popular Music, University of Rochester Arthur Satz Department of Music Eastman School of Music Main Points The Beatles’ “road to India” is mostly navigated by George Harrison John Lennon was also enthusiastic, Paul somewhat, Ringo not so much Harrison’s “road to India” can be divided into two kinds of influence: Musical influences—the actual sounds and structures of Indian music Philosophical and spiritual influences—elements that influence lyrics and lifestyle The musical influences begin in April 1965, become focused in fall 1966, and extend to mid 1968 The philosophical influences begin in late 1966 and continue through the rest of Harrison’s life Note: Harrison began using LSD in the spring of 1965 and discontinued in August 1967 Songs by other Beatles, Lennon especially, also reflect Indian influences The Three “Indian” songs of George Harrison “Love You To” recorded April 1966, released on Revolver, August 1966 “Within You Without You” recorded March, April 1967, released on Sgt Pepper, June 1967 “The Inner Light” recorded January, February 1968, released as b-side to “Lady Madonna,” March 1968 Three Aspects of “Indian” characteristics Use of some aspect of Indian philosophy or spirituality in the lyrics Use of Indian musical instruments Use of Indian musical features (rhythmic patterns, drone, texture, melodic elements) Musical Influences Ravi Shankar is principal influence on Harrison, though he does not enter the picture until mid 1966 April 1965: Beatles film restaurant scene for Help! Harrison falls in love with the sitar, buys one cheap Summer 1965: Beatles in LA hear about Shankar from McGuinn, Crosby (meet Elvis, discuss Yogananda) October 1965: “Norwegian Wood” recorded, released in December on Rubber Soul. -

RF Annual Report

PRESIDENT'S TEN-YEAR REVIEW ANNUAL REPORT1971 THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION THE ROCKEFELLER mr"nMnftTinN JAN 26 2001 LIBRARY 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation The pages of this report are printed on paper made from recycled fibers THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION 111 WEST 50TH STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10020 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation CONTENTS President's Ten-year Review 1 1971 Grants and Programs 105 Study Awards 143 Organizational Information 151 Financial Statements 161 1971 Appropriations and Payments 173 2003 The Rockefeller Foundation TRUSTEES AND TRUSTEE COMMITTEES April 1971—April 1972 DOUGLAS DILLON* Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER 3RD1 Honorary Chairman BOARD OF TRUSTEES BARRY BINGHAMS VERNON E. JORDAN, JR. FREDERICK SEITZ W. MICHAEL BLUMENTHALS CLARK KERB FRANK STANTON JOHN S. DICKEY MATHILDE KRIM MAURICE F. STRONG* DOUGLAS DILLON ALBERTO LLERAS CAMARGO CYRUS R. VANCE ROBERT H. EBERT BILL MOYEHS THOMAS J. WATSON, JR.4 ROBERT F. GOHEEN JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER 3RD2 CLIFTON R. WHARTON, JR. J. GEORGE HARRAR JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV W. BARRY WOOD, JR.5 THEODORE M. HESBURGH ROBERT V. ROOSA WHITNEY M. YOUNG, JR.6 ARTHUR A. HOUGHTON, JR. NEVIN S. SCRIMSHAW* EXECVTIVE COMMITTEE THE PRESIDENT Chairman ROBERT V. ROOSA THEODORE M. HESBURGH* _ _ _ _ alternate member DOUGLAS DILLON FREDERICK SEITZ ,, „ , PC VERNON E. JORDAN, JR. MATHILDE KRIM* FRANK STANTON alternate member BILL MoYEHS8 CYRUS R. VANCE* NEVJN S- SCRIMSHAW* JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER 3nn2 ROBERT F. GOHEEN alternate member alternate member FINANCE COMMITTEE Through June 30 Beginning July 1 DOUGLAS DILLON Chairman ROBERT V. ROOSA Chairman ROBERT V. ROOSA DOUGLAS DILLON* THOMAS J. -

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

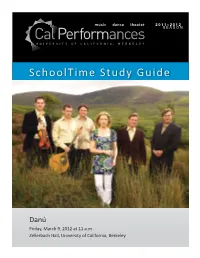

Danu Study Guide 11.12.Indd

SchoolTime Study Guide Danú Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 am, your class will a end a performance by Danú the award- winning Irish band. Hailing from historic County Waterford, Danú celebrates Irish music at its fi nest. The group’s energe c concerts feature a lively mix of both ancient music and original repertoire. For over a decade, these virtuosos on fl ute, n whistle, fi ddle, bu on accordion, bouzouki, and vocals have thrilled audiences, winning numerous interna onal awards and recording seven acclaimed albums. Using This Study Guide You can prepare your students for their Cal Performances fi eld trip with the materials in this study guide. Prior to the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student resource sheet on pages 2 & 3 and hand it out to your students several days before the performance. • Discuss the informa on About the Performance & Ar sts and Danú’s Instruments on pages 4-5 with your students. • Read to your students from About the Art Form on page 6-8 and About Ireland on pages 9-11. • Engage your students in two or more of the ac vi es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding ques ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 9. • Immerse students further into the art form by using the glossary and resource sec ons on pages 12 &15. At the performance: Students can ac vely par cipate during the performance by: • LISTENING CAREFULLY to the melodies, harmonies and rhythms • OBSERVING how the musicians and singers work together, some mes playing in solos, duets, trios and as an ensemble • THINKING ABOUT the culture, history, ideas and emo ons expressed through the music • MARVELING at the skill of the musicians • REFLECTING on the sounds and sights experienced at the theater. -

Candidates Prepare for Final Showdown

Matawan holds onto lead in Register Top Ten, 1B MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1878 ister )AY. NOV 8. 1988 VOL. 111 NO. .13 25 i Lawyer: Hunt Meet Candidates prepare not legal for final showdown By VIRGINIA KEMTDORRI8 bid to topple incumbent U.S. Sen. Frank Lautenberg. THE REGISTER BySEAMUSMcORAW The latest Eagleton poll, however, gives Lautenberg a THE REGISTER solid 12-point lead over the one-time Heisman Tro- phy winner and Rhodes scholar. MIDDLETOWN — The state On the congressional level, the race to fill How- Attorney General's Office will Politicians and campaign workers spent much of ard's seat — in which Libertarian Laura Stewart it look into whether the annual Hunt yesterday in a last-minute push before today's general also a candidate — has drawn national attention, in Race Meet operates legally be- election. pan because it is one of the few seats nationwide with cause of inquiries made by local "We've been out all weekend," said Wendy Do- no incumbent. attorney Larry S. Loigman. nath, a spokesman for 3rd Congressional District The picture is further complicated by the fact that Loigman, who has vowed to hopeful Joseph Azzolina. with Howard's death and the resignation of Demo- "make sure that this year's hunt is Azzolina is hoping to top Democratic state Sen. cratic Rep. Peter Rodino of Newark, the state's pres- the last one," last month contacted Frank Pallone in the race to fill the seat left vacant by tige level in Congress is reported to be on the decline. -

Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in the Late Lancashire Witches: a Reel Crux?

Early Theatre 16.1 (2013), 139–49 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.16.1.8 Note Brett D. Hirsch Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in The Late Lancashire Witches: A Reel Crux? A memorable scene in act 3 of Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome’s The Late Lancashire Witches (first performed and published 1634) plays out the bewitching of a wedding party and the comedy that ensues. As the party- goers ‘beginne to daunce’ to ‘Selengers round’, the musicians instead ‘play another tune’ and ‘then fall into many’ (F4r).1 With both diabolical interven- tion (‘the Divell ride o’ your Fiddlestickes’) and alcoholic excess (‘drunken rogues’) suspected as causes of the confusion, Doughty instructs the musi- cians to ‘begin againe soberly’ with another tune, ‘The Beginning of the World’, but the result is more chaos, with ‘Every one [playing] a seuerall tune’ at once (F4r). The music then suddenly ceases altogether, despite the fiddlers claiming that they play ‘as loud as [they] can possibly’, before smashing their instruments in frustration (F4v). With neither fiddles nor any doubt left that witchcraft is to blame, Whet- stone calls in a piper as a substitute since it is well known that ‘no Witchcraft can take hold of a Lancashire Bag-pipe, for itselfe is able to charme the Divell’ (F4v). Instructed to play ‘a lusty Horne-pipe’, the piper plays with ‘all [join- ing] into the daunce’, both ‘young and old’ (G1r). The stage directions call for the bride and bridegroom, Lawrence and Parnell, to ‘reele in the daunce’ (G1r). At the end of the dance, which concludes the scene, the piper vanishes ‘no bodie knowes how’ along with Moll Spencer, one of the dancers who, unbeknownst to the rest of the party, is the witch responsible (G1r).