Common Right and Private Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Casterton Parish Plan 2005

A1 © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Rutland Council District Council Licence No. LA 100018056 With Special thanks to: 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. History 3. Community and household 4. Transport and traffic 5. Crime and community safety 6. Sport and leisure 7. Youth 8. Village church 9. Education 10. Retail services 11. Farming and heritage 12. Conservation and the environment 13. Planning and development 14. Health and social services 15. Information and communication 16. Local councils 17. Conclusion 18. Action plan 3 INTRODUCTION PARISH PLANS Parish plans are part of the “Vital Villages” initiative of the Countryside Agency, run locally through the Rural Community Council (Leicestershire & Rutland). A Parish Plan should provide a picture of a village, identifying through consultation the concerns and needs of its residents. From the plan villages should identify actions to improve the village and the life of the community. The resulting Village Action Plan is then used to inform the County Council, through the Parish Council. Parish Plans have a statutory place in local government. GREAT CASTERTON PARISH PLAN Great Casterton’s Parish Plan started with a meeting of villagers in June 2002. There was particular interest because of a contentious planning decision imposed by the County Council on the village. The Community Development Officer for Rutland, Adele Stainsby, explained the purpose of the plan and the benefits for the village. A committee was formed, and a constitution drawn up. The Parish Council promised a small initial grant while an application for Countryside Agency funding was prepared. The money granted was to be balanced by the voluntary work of villagers. -

103938 Whissendine Cottage SAV.Indd

A SUBSTANTIAL PERIOD DWELLING AND ATTACHED OUTBUILDINGS WITH PLANNING PERMISSION FOR 5 DETACHED DWELLINGS. AVAILABLE AS A WHOLE OR IN SEPARATE LOTS. Whissendine Cottage Whissendine, Oakham, Rutland, LE15 7ET Whissendine Cottage 32 Main Street, Whissendine, Oakham, Rutland, LE15 7ET A SUBSTANTIAL PERIOD DWELLING AND ATTACHED OUTBUILDINGS WITHIN A DESIRABLE RUTLAND VILLAGE WITH PLANNING PERMISSION FOR 5 DETACHED DWELLINGS. IN TOTAL CIRCA 4 ACRES. AVAILABLE AS A WHOLE OR IN SEPARATE LOTS. Oakham 4.8 miles ♦ Melton Mowbray 6.4 miles A1 8.9 miles ♦ Uppingham 11.6 miles ♦ Stamford 16 miles Grantham 19.1 miles (London Kings Cross from 69 minutes) Corby 19.7 miles ♦ Leicester 24.9 miles ♦ Nottingham 29.6 miles ♦ Peterborough 29.9 miles (London King Cross from 51 minutes) Accommodation Dining Hall ♦ Drawing Room ♦ Breakfast Kitchen ♦ Sitting Room Family Room ♦ Study ♦ Utility Room ♦ Cloakroom ♦ Cellar Eight Bedrooms ♦ Three Bathrooms ♦ Snooker Room Games Room Gardens & Outbuildings Gardens of approximately 1.58 acres (edged in blue) Additional 2.37 acres with planning permission Beautifully landscaped grounds ♦ A plethora of useful outbuildings with further potential (STP) Available as a whole or in separate lots Development Site Outline planning for 5 detached dwellings ♦ Site area of approximately 2.37 acres ♦ All matters reserved except for access ♦ No Section 106 Contributions or CIL (if built in accordance with existing permission). Situation Whissendine is a picturesque village in the county of Rutland, lying north west of the county town, Oakham. Within the village lies St. Andrews Church, one of the largest in Rutland and a windmill producing flour which can be bought at the village shop. -

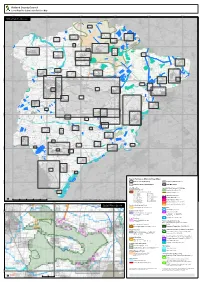

Rutland Main Map A0 Portrait

Rutland County Council Local Plan Pre-Submission Policies Map 480000 485000 490000 495000 500000 505000 Rutland County - Main map Thistleton Inset 53 Stretton (west) Clipsham Inset 51 Market Overton Inset 13 Inset 35 Teigh Inset 52 Stretton Inset 50 Barrow Greetham Inset 4 Inset 25 Cottesmore (north) 315000 Whissendine Inset 15 Inset 61 Greetham (east) Inset 26 Ashwell Cottesmore Inset 1 Inset 14 Pickworth Inset 40 Essendine Inset 20 Cottesmore (south) Inset 16 Ashwell (south) Langham Inset 2 Ryhall Exton Inset 30 Inset 45 Burley Inset 21 Inset 11 Oakham & Barleythorpe Belmesthorpe Inset 38 Little Casterton Inset 6 Rutland Water Inset 31 Inset 44 310000 Tickencote Great Inset 55 Casterton Oakham town centre & Toll Bar Inset 39 Empingham Inset 24 Whitwell Stamford North (Quarry Farm) Inset 19 Inset 62 Inset 48 Egleton Hambleton Ketton Inset 18 Inset 27 Inset 28 Braunston-in-Rutland Inset 9 Tinwell Inset 56 Brooke Inset 10 Edith Weston Inset 17 Ketton (central) Inset 29 305000 Manton Inset 34 Lyndon Inset 33 St. George's Garden Community Inset 64 North Luffenham Wing Inset 37 Inset 63 Pilton Ridlington Preston Inset 41 Inset 43 Inset 42 South Luffenham Inset 47 Belton-in-Rutland Inset 7 Ayston Inset 3 Morcott Wardley Uppingham Glaston Inset 36 Tixover Inset 60 Inset 58 Inset 23 Barrowden Inset 57 Inset 5 Uppingham town centre Inset 59 300000 Bisbrooke Inset 8 Seaton Inset 46 Eyebrook Reservoir Inset 22 Lyddington Inset 32 Stoke Dry Inset 49 Thorpe by Water Inset 54 Key to Policies on Main and Inset Maps Rutland County Boundary Adjoining -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

BRONZE AGE SETTLEMENT at RIDLINGTON, RUTLAND Matthew Beamish

01 Ridlington - Beamish 30/9/05 3:19 pm Page 1 BRONZE AGE SETTLEMENT AT RIDLINGTON, RUTLAND Matthew Beamish with contributions from Lynden Cooper, Alan Hogg, Patrick Marsden, and Angela Monckton A post-ring roundhouse and adjacent structure were recorded by University of Leicester Archaeological Services, during archaeological recording preceding laying of the Wing to Whatborough Hill trunk main in 1996 by Anglian Water plc. The form of the roundhouse together with the radiocarbon dating of charred grains and finds of pottery and flint indicate that the remains stemmed from occupation toward the end of the second millennium B.C. The distribution of charred cereal remains within the postholes indicates that grain including barley was processed and stored on site. A pit containing a small quantity of Beaker style pottery was also recorded to the east, whilst a palaeolith was recovered from the infill of a cryogenic fissure. The remains were discovered on the northern edge of a flat plateau of Northamptonshire Sand Ironstone at between 176 and 177m ODSK832023). The plateau forms a widening of a west–east ridge, a natural route way, above northern slopes down into the Chater Valley, and abrupt escarpments above the parishes of Ayston and Belton to the south (illus. 2). Near to the site, springs issue from just below the 160m and 130m contours to the north and south east respectively and ponds exist to the east corresponding with a boulder clay cap. The area was targeted for investigation as it lay on the northern fringe of a substantial Mesolithic/Early Neolithic flint scatter (LE5661, 5662, 5663) (illus. -

River Eye SSSI: Strategic Restoration Plan

Natural England Commissioned Report NECR184 River Eye SSSI: Strategic Restoration Plan Technical Report First published 15 July 2015 www.gov.uk/natural-england Foreword This report was commissioned by Natural England and overseen by a steering group convened by Natural England in partnership with the Environment Agency. The report was produced by Royal HaskoningDHV. The views in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Natural England. Background The River Eye is a semi-natural lowland river The water quality is being addressed, but the which rises at Bescaby, approximately 10km physical character of the river channel also north east of Melton Mowbray. It flows for needs to be restored to secure good ecological approximately 21km, becoming the River and hydrological functioning. Wreake as it flows through Melton Mowbray and around Sysonby Lodge. As a result of its In 2014, a geomorphological appraisal of the characteristics as an exceptional example of a River Eye was carried out by Royal semi-natural lowland river, an area covering HaskoningDHV, the result of this appraisal 13.65ha and a length of approximately 7.5km enabled Royal HaskoningDHV to produce the was designated a Site of Special Scientific River Eye SSSI technical report and restoration Interest. This area, situated between Stapleford vision; combined make up the River Eye (National Grid Reference [NGR] SK 802186) Restoration Strategy. This report identifies and and Melton Mowbray (NGR SK 764188) equates prioritises physical restoration measures that will to approximately 40% of the total length of the help to achieve favourable condition and water River Eye. -

Stapleford Road, Whissendine – Offers Over £500,000

Stapleford Road, Whissendine – Offers over £500,000 • Bay Fronted Detached Family Home • Sitting Room With Original Fireplace • Character Features Throughout • Four Bedrooms, Two Ensuite • Detached 4 3 3 Garage Recently Redecorated • Attractive Enclosed Gardens House Off Road • Farmhouse Style Kitchen With AGA • Garaging & Off Road Parking Parking Property Description Osprey are proud to present this attractive bay-fronted detached family home, situated in one of Rutland’s most popular villages. The property has been recently refurbished, whilst maintaining its charm and original features throughout. The well-presented accommodation comprises an entrance hallway with doors off leading to the bay-fronted sitting room with open fire, study and dining room also with bay window and original fireplace. Further is a boot room with French double doors opening onto the rear garden, farmhouse style breakfast kitchen with original tiled flooring and AGA and stairs with storage under. Stairs rising to the first floor lead to an L shaped landing area with four good sized bedrooms off, two with ensuite facilities and a refitted family bathroom with stand-alone tub. Externally, the property offers off road parking and garaging to the front. To the rear, the garden has been fully landscaped to offer an area of lawn, patio, seating area and pond. Situated in a quiet position within this well-regarded Rutland village. The Location Whissendine is a highly regarded village within the county of Rutland in the East Midlands. There are a range of amenities to be found including a public house, village store and post office, hairdressers, Primary School rated ‘outstanding’ in the latest Ofsted report, active village hall and church. -

LIST of SCHEDULED MONUMENTS in LEICESTERSHIRE and RUTLAND (To 31 March 1956)

LIST OF SCHEDULED MONUMENTS IN LEICESTERSHIRE AND RUTLAND (to 31 March 1956) This list has been compiled with the co-operation of the Ancient Monuments Division of the Ministry of Works. A Monument under Guardianship is one for the conservation of which the Ministry accepts responsibility. A Scheduled Monument is protected in that no alterations of any kind may be made to it (including ploughing and excavation) without three months' notice being given to the Ministry. It is then open to the Ministry to take steps to secure the permanent preservation of the monument, or alternatively to allow its destruction after suitable excavation or recording has been carried out. It is emphasised that scheduling implies no right of access to the general public, and permission should always be sought before entering any property. The Hon. Secretary of the Leicestershire Arch::eological and Historical Society will be grateful for suggestions regarding suitable additions to this list. The Act excludes churches and chapels in regular use and houses in occupation. In the list below, all monuments (other than those in Leicester itself) =1r.e referred to by the civil parishes in which they are located, the name of the c1V1l parish being given in italics: e.g., Lockingion-Hemington. LEICESTERSHIRE I. MONUMENTS UNDER GUARDIANSHIP All open to the public. A printed guide-book is available to each. The Jewry Wall, Leicester. Roman. Admission free. Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Not open on Sundays. K. M. Kenyon (Excavations at the Jewry Wall Site, Leicester, r948; Arch. Journ., cxii. 160.) Kirby Castle, Kirby Muxloe. -

Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 418 HOUSING, ENGLAND The Housing (Right to Buy) (Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004 Made - - - - 20th February 2004 Laid before Parliament 25th February 2004 Coming into force - - 17th March 2004 The First Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by sections 157(1)(c) and 3(a) of the Housing Act 1985(1) hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Housing (Right to Buy) (Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 17th March 2004. (2) In this Order “the Act” means the Housing Act 1985. Designated rural areas 2. The areas specified in the Schedule are designated as rural areas for the purposes of section 157 of the Act. Designated regions 3.—(1) In relation to a dwelling-house which is situated in a rural area designated by article 2 and listed in Part 1 of the Schedule, the designated region for the purposes of section 157(3) of the Act shall be the district of Forest of Dean. (2) In relation to a dwelling-house which is situated in a rural area designated by article 2 and listed in Part 2 of the Schedule, the designated region for the purposes of section 157(3) of the Act shall be the district of Rochford. (1) 1985 c. -

Royal Forest Trail

Once there was a large forest on the borders of Rutland called the Royal Forest of Leighfield. Now only traces remain, like Prior’s Coppice, near Leighfield Lodge. The plentiful hedgerows and small fields in the area also give hints about the past vegetation cover. Villages, like Belton and Braunston, once deeply situated in the forest, are square shaped. This is considered to be due to their origin as enclosures within the forest where the first houses surrounded an open space into which animals could be driven for their protection and greater security - rather like the covered wagon circle in the American West. This eventually produced a ‘hollow-centred’ village later filled in by buildings. In Braunston the process of filling in the centre had been going on for many centuries. Ridlington betrays its forest proximity by its ‘dead-end’ road, continued only by farm tracks today. The forest blocked entry in this direction. Indeed, if you look at the 2 ½ inch O.S map you will notice that there are no through roads between Belton and Braunston due to the forest acting as a physical administrative barrier. To find out more about this area, follow this trail… You can start in Oakham, going west out of town on the Cold Overton Road, then 2nd left onto West Road towards Braunston. Going up the hill to Braunston. In Braunston, walk around to see the old buildings such as Cheseldyn Farm and Quaintree Hall; go down to the charming little bridge over the River Gwash (the stream flowing into Rutland Water). -

Rutland County Council Review of Indoor Sport and Recreation Facilities in Rutland

Rutland County Council Review of Indoor Sport and Recreation Facilities in Rutland Audit and Needs Assessment Report from Sport Structures Ltd Sport Structures Ltd, Company Number 4492940 PO Box 10710, Sutton Coldfield, B75 5YG (t): 0845 241 7195 (m): 07766 768 474 (f): 0845 241 7197 (e): [email protected] (w): www.sportstructures.com A report from Sport Structures Ltd Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 7 2 Sport and recreation context .......................................................................................... 7 Adult participation (16+) in sport and active recreation ........................................................... 9 Young people (14-25) in sport and active recreation .............................................................. 13 3 Assessment and audit approach ................................................................................... 15 4 Quantity and quality of indoor sports facilities ................................................................ 18 5 Accessibility and demand from users ............................................................................. 28 User data from main facilities ........................................................................................... 33 Demand from clubs, groups and classes .......................................................................... -

Download the 2006 Leicestershire Historian

Leicestershire Historian No 42 (2006) Contents Editorial 2 The Coming of Printing to Leicester John Hinks 3 “What is a Town without a Newspaper?” The formative years of newspapers in Loughborough up to the First World War Diana Dixon 7 The Jewish Burial Grounds at Gilroes Cemetery, Leicester Carol Cambers 11 Is Sutton in the Elms the oldest Baptist Church in Leicestershire? Erica Statham 16 “Sudden death sudden glory” A gravestone at Sutton in the Elms Jon Dean 17 Barwell Rectory in the 19th and early 20th centuries John V.G. Williams 18 A Survival from Georgian Leicester: Number 17 Friar Lane Terry Y. Cocks 21 Poor Relief in Nailstone 1799 Kathy Harman 24 The Prince Regent’s Visit to Belvoir, 1814 J. D. Bennett 27 “So hot an affair” Leicestershire men in the Crimean War – the Great Redan Robin P. Jenkins 29 Stephen Hilton – Industrialist, Churchman and Mayor Neil Crutchley 33 Nature in Trust: The First 50 Years of the Leicestershire and Rutland Wildlife Trust Anthony Squires 36 Opening up village history to the world: Leicestershire Villages Web Portal project Chris Poole 40 The Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland Historic Landscape Characterisation project John Robinson 42 University of Leicester – completed M.A. dissertations about Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland Centre for English Local 43 History Recent Publications Ed John Hinks 46 Editor: Joyce Lee Published by the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, The Guildhall, Leicester, LE1 5FQ 2006 Leicestershire Historian 2006 Editorial The articles in this years Leicestershire Historian once again demonstrate the overall diversity of the subject, some of the richness of the sources available, and the varying ways in which locality can be interpreted.