Department of English and American Studies 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

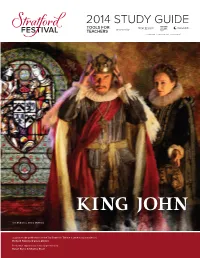

STUDY GUIDE TOOLS for TEACHERS Sponsored By

2014 STUDY GUIDE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by Tom McCamus, Seana McKenna Support for the 2014 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre is generously provided by Richard Rooney & Laura Dinner Production support is generously provided by Karon Bales & Charles Beall Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 6 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 7 Sources and Origins .................................................................................................... 8 Stratford Festival Production History ......................................................................... 9 The Production Artistic Team and Cast ............................................................................................... 10 Lesson Plans and Activities Creating Atmosphere .......................................................................................... 11 Mad World, Mad Kings, Mad Composition! ........................................................ 14 Discussion Topics .............................................................................................. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

COMPTES RENDUS the Life and Times of Dalton Camp

James Ferrabee COMPTES RENDUS The life and times of Dalton Camp Geoffrey Stevens, The Player: The Life and Times of Dalton Camp, Toronto, Key Porter Books, 2003. Review by James Ferrabee n the mid-1950s there was little dian politics on the provincial and For the next 30 years he was an observ- hope a Conservative Government federal scene. er rather than a participant, turning to I would or could be elected in In all, Camp watched over and writing columns for the Toronto Star Ottawa. By 1955, the Liberals had directed 28 elections. His helped create and participating in debates about pol- ruled with little effective opposition and fertilize several Tory dynasties on itics on TV, radio and in public debates. for 20 years. It felt like 40 years. Who the provincial scene, including Robert He was, in short, “a player” which is was going to stop them? Stanfield’s in Nova Scotia (11 years), also the title of Geoffrey Stevens superbly At universities, Canadian history Richard Hatfield’s in New Brunswick (16 researched and cogently written biogra- texts read like a slightly revised ver- years), William Davis’ in Ontario (14 phy of Camp. Not everyone, including sion of the history of the Liberal Party. years) and Duff Roblin’s in Manitoba (11 many who were deeply involved in poli- No one found that strange. The pre- years). He helped direct John Diefenbak- tics in the 1960s and 1970s, will want to eminent historian was A.R.M. Lower er’s campaigns in 1957, 1958, 1962 and read it. -

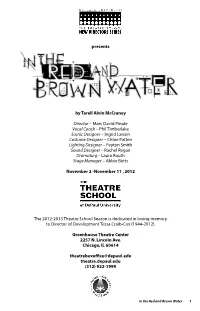

Presents by Tarell Alvin Mccraney Director – Marc David Pinate Vocal

presents by Tarell Alvin McCraney Director – Marc David Pinate Vocal Coach – Phil Timberlake Scenic Designer – Ingrid Larson Costume Designer – Chloe Patten Lighting Designer – Peyton Smith Sound Designer – Rachel Regan Dramaturg – Laura Routh Stage Manager – Abbie Betts November 2 -November 11 , 2012 The 2012-2013 Theatre School Season is dedicated in loving memory to Director of Development Tessa Craib-Cox (1944-2012). Greenhouse Theatre Center 2257 N. Lincoln Ave. Chicago, IL 60614 [email protected] theatre.depaul.edu (312) 922-1999 In the Red and Brown Water 1 CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE ) PRODUCTION STAFF O Li Roon/The Man from State ..............................................................................Matthew Browning Faculty Advisor ............................................................................................................................ Lisa Portes Nia ........................................................................................................................................... Adrienne Jones Assistant Director ....................................................................................................................Lucas Baisch Oya .............................................................................................................................................Kiandra Layne Elegba ...........................................................................................................................................James Lewis Assistant Stage Manager .................................................................................................... -

Book Reviews – October 2012

Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies Issue 24 October 2012 Book Reviews – October 2012 Table of Contents Jacques Rivette By Douglas Morrey and Alison Smith Alain Robbe-Grillet By John Phillips A Review by Jonathan L. Owen ............................................................... 3 Music and Politics By John Street Wagner and Cinema Edited by Jeongwon Joe and Sander L. Gilman A Review by Nathan Waddell ................................................................ 11 Disney, Pixar, and the Hidden Messages of Children’s Films By M. Keith Booker Demystifying Disney: A History of Disney Feature Animation By Chris Pallant A Review by Noel Brown ...................................................................... 17 Virtual Voyages: Cinema and Travel Edited by Jeffrey Ruoff Cinematic Journeys: Film and Movement By Dimitris Eleftheriotis A Review by Sofia Sampaio .................................................................. 26 1 Book Reviews Jerry Lewis by Chris Fujiwara Atom Egoyan by Emma Wilson Andrei Tarkovsky by Sean Martin A review by Adam Jones ...................................................................... 34 The Comedy of Chaplin: Artistry in Motion By Dan Kamin Disappearing Tricks: Silent Film, Houdini and the New Magic of the Twentieth Century By Matthew Solomon A review by Bruce Bennett ................................................................... 42 Von Sternberg By John Baxter Willing Seduction: The Blue Angel, Marlene Dietrich and Mass Culture By Barbara Kosta A Review by Elaine Lennon -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

February 13 , 2003 •

formerly the trent report 13 feb. 2003 focusYour connection to news at Canada’s Outstanding Small University trent innews the Trent English Prof. a cosmic Geoffrey Eathorne combination was quoted in a January 18 Globe and Mail world’s beauty through images article about the Bloomsbury she captures on film. “Your val- era and its effect on current ues become entrenched after you style trends. fly in space,” Dr. Bondar explains. “I was already environment- In a minded and came back from January space with a clear sense of pur- 23 pose.” Toronto A quote from Passionate Vision, Star arti- a beautiful book of Dr. Bondar’s cle that photography that focuses on docu- Canada’s national parks, explains mented her viewpoint further. She writes: applications to nursing pro- “For a brief moment, I lived grams in Canada for fall, beyond Earth, ceasing to exist on 2003, Trent’s B.Sc.N. program land or sea. Space isolated me was noted. The rise in nursing from Earth’s complex, beautiful applications was cited as and precious life, leaving me good news for the profession with only faint memories of bird- and the health care system. song, splashing water, warm scented plants. My photographs Dr. Chris Metcalfe was fea- are of a land that protects this tured in a Feb. 9 CTV televi- fragile beauty. This is the passion sion segment that looked at of my vision.” She also writes: pharmaceutical drug traces in “No two people are alike, so no drinking water. This was also two space experiences can be the focus of a front page Globe alike; but my flight left me with a and Mail article on Monday, whole new view of my science, Feb.