Georgia's Mountain Bogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrub Swamp State Rank: S5 - Secure

Shrub Swamp State Rank: S5 - Secure cover of tall shrubs with Shrub Swamp Communities are a well decomposed organic common and variable type of wetlands soils. If highbush occurring on seasonally or temporarily blueberries are dominant flooded soils; They are often found in the transition zone between emergent the community is likely to marshes and swamp forests; be a Highbush Blueberry Thicket, often occurring on stunted trees. The herbaceous layer of peat. Acidic Shrub Fens are shrub swamps is often sparse and species- peatlands, dominated by poor. A mixture of species might typically low growing shrubs, along include cinnamon, sensitive, royal, or with sphagnum moss and marsh fern, common arrowhead, skunk herbaceous species of Shrub Swamp along shoreline. Photo: Patricia cabbage, sedges, bluejoint grass, bur-reed, varying abundance. Deep Serrentino, Consulting Wildlife Ecologist. swamp candles, clearweed, and Emergent Marshes and Description: Wetland shrubs dominate turtlehead. Invasive species include reed Shallow Emergent Marshes Cottontail, have easy access to the shrubs Shrub Swamps. Shrub height may be from canary grass, glossy alder-buckthorn, are graminoid dominated wetlands with and protection in the dense thickets. The <1m to 5 meters, of uniform height or common buckthorn, and purple <25% cover of tall shrubs. Acidic larvae of many rare and common moth mixed. Shrub density can be variable, loosestrife. Pondshore/Lakeshore Communities are species feed on a variety of shrubs and from dense (>75% cover) to fairly open broadly defined, variable shorelines associated herbaceous plants in shrub (25-75% cover) with graminoid, around open water. Shorelines often swamps throughout Massachusetts. herbaceous, or open water areas between merge into swamps or marshes. -

South Acton Swamps Beginning with Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Habitat South Acton Swamps

Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance: South Acton Swamps Beginning with Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Habitat South Acton Swamps Biophysical Region • Sebago-Ossipee Hills and Plain WHY IS THIS AREA SIGNIFICANT? The series of broad basins supporting forested wetlands, Rare Animals peatlands, marshes and open water systems surrounded Blanding’s Turtles by forested hillsides in the South Acton Swamps Focus Wood Turtle Area sustain a wide diversity of plant and animal habitats Ribbon Snake including ecosystems and natural communities of Rare Plants statewide significance, rare plant and rare animal species. Small whorled-pogonia Spotted Wintergreen OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION Swamp Saxifrage Work with willing landowners to permanently protect » Rare and Exemplary Natural Communities the significant features in the Focus Area. Grassy Shrub Marsh » Maintain enhanced riparian buffers. Streamshore Ecosystem » Encourage best management practices for forestry Unpatterned Fen Ecosystem activities near wetlands, water bodies and significant features. Significant Wildlife Habitats Maintain the natural hydrology by avoiding drainage Inland Wading Bird and Waterfowl Habitat » Significant Vernal Pool or impoundment of the wetlands, streams or adjacent Deer Wintering Area water bodies. Refer to the Beginning with Habitat Online Toolbox for more conservation opportunities: www.beginningwith- habitat.org/toolbox/about_toolbox.html Beginning with Habitat Online Toolbox: www. beginningwithhabitat.org/toolbox/about_toolbox.html. Photo credits, top to bottom: MNAP, MDIFW, MNAP, MNAP, Jonathan Mays 1 Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance: South Acton Swamps South Acton Swamps Black Pond Fen, Maine Natural Areas Program FOCUS AREA OVERVIEW RARE AND EXEMPLARY NATURAL COMMUNITIES The South Acton Swamps Focus Area covers approximately 3,600 acres and is a series of moderately broad basins sur- Black Pond Fen, located in the southern portions of the Focus rounded by gentle to steep forested hillsides. -

Western Samoa

A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania In: Scott, D.A. (ed.) 1993. A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania. IWRB, Slimbridge, U.K. and AWB, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania WESTERN SAMOA INTRODUCTION by Cedric Schuster Department of Lands and Environment Area: 2,935 sq.km. Population: 170,000. Western Samoa is an independent state in the South Pacific situated between latitudes 13° and 14°30' South and longitudes 171° and 173° West, approximately 1,000 km northeast of Fiji. The state comprises two main inhabited islands, Savai'i (1,820 sq.km) and Upolu (1,105 sq.km), and seven islets, two of which are inhabited. Western Samoa is an oceanic volcanic archipelago that originated in the Pliocene. The islands were formed in a westerly direction with the oldest eruption, the Fagaloa volcanics, on the eastern side. The islands are still volcanically active, with the last two eruptions being in 1760 and 1905-11 respectively. Much of the country is mountainous, with Mount Silisili (1,858 m) on Savai'i being the highest point. Western Samoa has a wet tropical climate with temperatures ranging between 17°C and 34°C and an average temperature of 26.5°C. The temperature difference between the rainy season (November to March) and the dry season (May to October) is only 2°C. Rainfall is heavy, with a minimum of 2,000 mm in all places. The islands are strongly influenced by the trade winds, with the Southeast Trades blowing 82% of the time from April to October and 54% of the time from May to November. -

PLTA-0103 Nature Conservancy 3/19/04 4:00 PM Page 1

PLTA-0103 Nature Conservancy 3/19/04 4:00 PM Page 1 ............................................................. Pennsylvania’s Land Trusts The Nature Conservancy About Land Trusts Conservation Options Conserving our Commonwealth Pennsylvania Chapter Land trusts are charitable organizations that conserve land Land trusts and landowners as well as government can by purchasing or accepting donations of land and conservation access a variety of voluntary tools for conserving special ................................................................ easements. Land trust work is based on voluntary agreements places. The basic tools are described below. The privilege of possessing Produced by the the earth entails the Pennsylvania Land Trust Association with landowners and creating projects with win-win A land trust can acquire land. The land trust then responsibility of passing it on, working in partnership with outcomes for communities. takes care of the property as a wildlife preserve, the better for our use, Pennsylvania’s land trusts Nearly a hundred land trusts work to protect important public recreation area or other conservation purpose. not only to immediate posterity, but to the unknown future, with financial support from the lands across Pennsylvania. Governed by unpaid A landowner and land trust may create an the nature of which is not William Penn Foundation, Have You Been to the Bog? boards of directors, they range from all-volunteer agreement known as a conservation easement. given us to know. an anonymous donor and the groups working in a single municipality The easement limits certain uses on all or a ~ Aldo Leopold Pennsylvania Department of Conservation n spring days, the Tannersville Cranberry Bog This kind of wonder saved the bog for today and for to large multi-county organizations with portion of a property for conservation and Natural Resources belongs to fourth-graders. -

Laurentian-Acadian Wet Meadow-Shrub Swamp

Laurentian-Acadian Wet Meadow-Shrub Swamp Macrogroup: Wet Meadow / Shrub Marsh yourStateNatural Heritage Ecologist for more information about this habitat. This is modeledmap a distributiononbased current and is data nota substitute for field inventory. based Contact © Maine Natural Areas Program Description: A shrub-dominated swamp or wet meadow on mineral soils characteristic of the glaciated Northeast and scattered areas southward. Examples often occur in association with lakes and ponds or streams, and can be small and solitary pockets or, more often, part of a larger wetland complex. The habitat can have a patchwork of shrub and herb dominance. Typical species include willow, red-osier dogwood, alder, buttonbush, meadowsweet, bluejoint grass, tall sedges, and rushes. Trees are generally absent or thinly scattered. State Distribution: CT, DE, MA, MD, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VA, VT, WV Total Habitat Acreage: 990,077 Ecological Setting and Natural Processes: Percent Conserved: 25.5% Shrub swamps and wet meadows are associated with lakes State State GAP 1&2 GAP 3 Unsecured and ponds and along headwater and larger streams where State Habitat % Acreage (acres) (acres) (acres) the water level does not fluctuate greatly. They are ME 30% 297,075 11,928 39,478 245,668 commonly flooded for part of the growing season but NY 30% 293,979 59,329 38,332 196,318 generally do not have standing water throughout the season. This is a dynamic system that may return to marsh in beaver- MA 8% 76,718 4,358 17,980 54,380 impounded areas or succeed to wooded swamp with NJ 7% 68,351 16,148 9,221 42,983 sediment accumulation or water subsidence. -

Lowland Raised Bog (UK BAP Priority Habitat Description)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Habitat Descriptions Lowland Raised Bog From: UK Biodiversity Action Plan; Priority Habitat Descriptions. BRIG (ed. Ant Maddock) 2008. This document is available from: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5706 For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5155 Please note: this document was uploaded in November 2016, and replaces an earlier version, in order to correct a broken web-link. No other changes have been made. The earlier version can be viewed and downloaded from The National Archives: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150302161254/http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page- 5706 Lowland Raised Bog The definition of this habitat remains unchanged from the pre-existing Habitat Action Plan (https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110303150026/http://www.ukbap.org.uk/UKPl ans.aspx?ID=20, a summary of which appears below. Lowland raised bogs are peatland ecosystems which develop primarily, but not exclusively, in lowland areas such as the head of estuaries, along river flood-plains and in topographic depressions. In such locations drainage may be impeded by a high groundwater table, or by low permeability substrata such as estuarine, glacial or lacustrine clays. The resultant waterlogging provides anaerobic conditions which slow down the decomposition of plant material which in turn leads to an accumulation of peat. Continued accrual of peat elevates the bog surface above regional groundwater levels to form a gently-curving dome from which the term ‘raised’ bog is derived. The thickness of the peat mantle varies considerably but can exceed 12m. -

Swamps Include a Broad Range

PART IV: Wetland Management SWAMPS wamps include a broad range port more woody vegetation. of wetlands that have stand- Occasional flooding or several Sing or slowly moving water years of wet weather can slow this and are dominated by trees or process, and several dry years can shrubs. Swamps differ from speed it up. marshes in that swamps do not contain large amounts of cattails, Swamps provide habitat for sedges, bulrushes, and other non- mink, muskrats, beaver, otter, deer, woody aquatic plants. However, black bear, squirrels, hares, barred these plants may appear around owls, various species of woodpeck- swamp edges or in openings. ers, wood ducks, nuthatches, sev- mink Michigan swamps include conifer eral kinds of warblers, black- swamps, hardwood swamps, mixed capped chickadees, snakes, turtles, prise much of the overall loss-- conifer-hardwood swamps, and frogs, toads, butterflies, dragon- about two-thirds of the original 5.5 shrub swamps. Swamps and low- flies, and many other insects. million acres of conifer swamps land forests are very similar and Uncommon animals such as red- have either been drained or con- are often one in the same. shouldered hawks, cerulean and verted by logging activity to low- However, swamps are often wetter prothonatory warblers, Indiana land hardwood, farmland, marshes for a longer period throughout the bats, smallmouth salamanders, and or shrub swamps. year and have deeper standing Blanchard's cricket frog, all rely on water than lowland forests. These swamps for survival. Types of Swamps lowland forests may be seasonal Northern white cedar and black wetlands. About one-third to one-half of spruce dominate most conifer Michigan's wetland acreage has swamps in northern Michigan, Like most wetlands, swamps been lost since 1800. -

Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries

E3: ECOSYSTEMS, ENERGY FLOW, & EDUCATION Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries Eco-systems, Energy Flow, and Education: Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries CONTENT OUTLINE Big Idea / Objectives / Driving Questions 3 Selby Gardens’ Field Study Opportunities 3 - 4 Background Information: 5 - 7 What is an Estuary? 5 Why are Estuaries Important? 5 Why Protect Estuaries? 6 What are Mangrove Wetlands? 6 Why are Mangrove Wetlands Important? 7 Endangered Mangroves 7 Grade Level Units: 8 - 19 8 - 11 (K-3) “Welcome to the Wetlands” 12 - 15 (4-8) “A Magnificent Mangrove Maze” 16 - 19 (7-12) “Monitoring the Mangroves” Educator Resources & Appendix 20 - 22 2 Eco-systems, Energy Flow, and Education: Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries GRADE LEVEL: K-12 SUBJECT: Science (includes interdisciplinary Common Core connections & extension activities) BIG IDEA/OBJECTIVE: To help students broaden their understanding of the Coastal Wetlands of Southwest Florida (specifically focusing on estuaries and mangroves) and our individual and societal interconnectedness within it. Through completion of these units, students will explore and compare the unique contributions and environmental vulnerability of these precious ecosystems. UNIT TITLES/DRIVING QUESTIONS: (Please note: many of the activities span a range of age levels beyond that specifically listed and can be easily modified to meet the needs of diverse learners. For example, the bibomimicry water filtration activity can be used with learners of all ages. Information on modification for -

Guide for Constructed Wetlands

A Maintenance Guide for Constructed of the Southern WetlandsCoastal Plain Cover The constructed wetland featured on the cover was designed and photographed by Verdant Enterprises. Photographs Photographs in this books were taken by Christa Frangiamore Hayes, unless otherwise noted. Illustrations Illustrations for this publication were taken from the works of early naturalists and illustrators exploring the fauna and flora of the Southeast. Legacy of Abundance We have in our keeping a legacy of abundant, beautiful, and healthy natural communities. Human habitat often closely borders important natural wetland communities, and the way that we use these spaces—whether it’s a back yard or a public park—can reflect, celebrate, and protect nearby natural landscapes. Plant your garden to support this biologically rich region, and let native plant communities and ecologies inspire your landscape. A Maintenance Guide for Constructed of the Southern WetlandsCoastal Plain Thomas Angell Christa F. Hayes Katherine Perry 2015 Acknowledgments Our thanks to the following for their support of this wetland management guide: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (grant award #NA14NOS4190117), Georgia Department of Natural Resources (Coastal Resources and Wildlife Divisions), Coastal WildScapes, City of Midway, and Verdant Enterprises. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge The Nature Conservancy & The Orianne Society for their partnership. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of DNR, OCRM or NOAA. We would also like to thank the following professionals for their thoughtful input and review of this manual: Terrell Chipp Scott Coleman Sonny Emmert Tom Havens Jessica Higgins John Jensen Christi Lambert Eamonn Leonard Jan McKinnon Tara Merrill Jim Renner Dirk Stevenson Theresa Thom Lucy Thomas Jacob Thompson Mayor Clemontine F. -

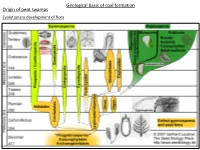

Geological Basis of Coal Formation Origin of Peat Swamps Evolutionary Development of Flora

Geological basis of coal formation Origin of peat swamps Evolutionary development of flora Peat swamp forests are tropical moist forests where waterlogged soil prevents dead leaves and wood from fully decomposing. Over time, this creates a thick layer of acidic peat. Large areas of these forests are being logged at high rates. True coal-seam formation took place only after Middle and Upper Devonian, when the plants spread over continent very rapidly. Devonian coal seams don’t have any economic value. The Devonian period was a time of great tectonic activity, as Euramerica and Gondwana drew closer together. The continent Euramerica (or Laurassia) was created in the early Devonian by the collision of Laurentia and Baltica, which rotated into the natural dry zone along the Tropic of Capricorn, which is formed as much in Paleozoic times as nowadays by the convergence of two great air-masses, the Hadley cell and the Ferrel cell. In these near- deserts, the Old Red Sandstone sedimentary beds formed, made red by the oxidized iron (hematite) characteristic of drought conditions. Sea levels were high worldwide, and much of the land lay under shallow seas, where tropical reef organisms lived. The deep, enormous Panthalassa (the "universal Devonian Paleogeography ocean") covered the rest of the planet. Other minor oceans were Paleo-Tethys, Proto- Tethys, Rheic Ocean, and Ural Ocean (which was closed during the collision with Siberia and Baltica). Carboniferous flora Upper Carboniferous is known as bituminous coal period. 30 m 7 m Permian coal deposits formed predominantly from Gymnosperm Cordaites. Cretaceous and Tertiary peats were formed from angiosperm floras. -

Maritime Shrub Swamp (Willow Subtype)

MARITIME SHRUB SWAMP (WILLOW SUBTYPE) Concept: Maritime Shrub Swamps are barrier island wetlands persistently dominated by large shrubs or small trees. The Willow Subtype encompasses examples dominated or codominated by Salix caroliniana. Distinguishing Features: The Willow Subtype is readily distinguished from all other communities by the combination of barrier island dune swale setting and dominance by Salix caroliniana. Salix may be present in small amounts in Maritime Swamp Forest or on edges of Interdune Ponds but does not dominate in these communities. Synonyms: Synonyms: Salix caroliniana / Sacciolepis striata - Boehmeria cylindrica Woodland (CEGL004222). Ecological Systems: Central Atlantic Coastal Plain Maritime Forest (CES203.261). Sites: The Willow Subtype occurs in wet dune swales in sheltered parts of barrier islands. Soils: Soils are sands, potentially with a shallow muck surface layer. They may be mapped as Conaby (Histic Humaquept) or Duckston (Typic Psammaquent) or may be inclusions of these soils in other map units. Hydrology: Hydrology is probably similar to that of the Dogwood Subtype, with fluctuating water levels that may cover the surface for entire seasons or may drop to saturated but not flooded conditions. Vegetation: The Willow Subtype is an open-to-potentially closed tall shrubland dominated by Salix caroliniana. Associated vegetation is not well characterized. Some Acer rubrum or other swamp tree species may be present in small numbers, and other trees rooted in adjacent communities may overhang. Morella cerifera or other shrubs may be present on the edges. Associated herbs may include Thelypteris palustris var. pubescens, Chasmanthium laxum, Hydrocotyle prolifera, Mikania scandens, Persicaria punctata, Boehmeria cylindrica, and potentially additional species shared with other subtypes. -

Strangmoor Bog the Unique Formation of Seney’S Natural National Landmark

Strangmoor Bog The Unique Formation of Seney’s Natural National Landmark Photo of a Strangmoor Bog, or String Bog, Seney NWR Schoolcraft County. Photo Courtesy of Josh Cohn—MNFI Seney National Wildlife Refuge, Schoolcraft County - Landmarks are a way to mark our path – easily recognizable, they prevent us from getting lost. From signs on a well-worn trail to the corner store in your neighborhood, landmarks can point us in the right direction. Landmarks are also how we mark our cultural identity and celebrate our past. We can erect a stature to honor a famous person’s work or build a monument to remind us of an important event. Landmarks - based on location or time - help us find our way. The National Natural Landmark Program “The patterned peat bog Natural landmarks are just as crucial and important for marking our within the National Natural paths and history, but instead of humans building a statue or monument to commemorate something, nature has already built Landmark at Seney marks the them. Through the National Natural Landmarks Program, the southern limit of patterned federal government recognizes and cares for natural landmarks, sites that contain rare geological features or plant and animal life. bogs in North America and is the largest and most striking The Secretary of the Interior designates these natural landmarks based on a number of traits: diversity, character, value to science example in Michigan and the and education, condition and rarity. Once designated, the National Lower 48 states..” Park Service administers the program, collaborating with landowners and other partners to conserve the nation’s natural heritage.