The Urban Segmentation Problem of Shenzhen, 42Nd Isocarp Congress 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Red Lines” Policy

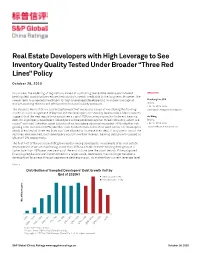

Real Estate Developers with High Leverage to See Inventory Quality Tested Under Broader “Three Red Lines” Policy October 28, 2020 In our view, the widening of regulations aimed at controlling real estate developers’ interest- ANALYSTS bearing debt would further reduce the industry’s overall credit risk in the long term. However, the nearer term may see less headroom for highly leveraged developers to finance in the capital Xiaoliang Liu, CFA market, pushing them to sell off inventory to ease liquidity pressure. Beijing +86-10-6516-6040 The People’s Bank of China said in September that measures aimed at monitoring the funding [email protected] and financial management of key real estate developers will steadily be expanded. Media reports suggest that the new regulations would see a cap of 15% on annual growth of interest-bearing Jin Wang debt for all property developers. Developers will be assessed against three indicators, which are Beijing called “red lines”: whether asset liability ratios (excluding advance) exceeded 70%; whether net +86-10-6516-6034 gearing ratio exceeded 100%; whether cash to short-term debt ratios went below 1.0. Developers [email protected] which breached all three red lines won’t be allowed to increase their debt. If only one or two of the red lines are breached, such developers would have their interest-bearing debt growth capped at 5% and 10% respectively. The first half of the year saw debt grow rapidly among developers. In a sample of 87 real estate developers that we are monitoring, more than 40% saw their interest-bearing debt grow at a faster rate than 15% year over year as of the end of June (see the chart below). -

*All Views Expressed in Written and Delivered Testimony Are Those of the Author Alone and Not of the U.S

February 20, 2020 Isaac B. Kardon, Ph.D. – Assistant Professor, U.S. Naval War College, China Maritime Studies Institute* Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing: China’s Military Power Projection and U.S. National Interests Panel II: China’s Development of Expeditionary Capabilities: “Bases and Access Points” 1. Where and how is China securing bases and other access points to preposition materiel and facilitate its expeditionary capabilities? Previous testimony has addressed the various military logistics vessels and transport aircraft that supply People’s Liberation Army (PLA) forces operating abroad. This method is costly, inefficient, and provides insufficient capacity to sustain longer and more complex military activities beyond the range of mainland logistics networks. Yet, with the notable exception of the sole military “support base” (baozhang jidi, 保障基地)1 in Djibouti, these platforms are the PLA’s only organic mode of “strategic delivery” (zhanlüe tousong, 战略投送) to project military power overseas. Lacking a network of overseas bases in the short to medium term, the PLA must rely on a variety of commercial access points in order to operate beyond the first island chain. Because the PLA Navy (PLAN) is the service branch to which virtually all of these missions fall, this testimony focuses on port facilities. The PLAN depends on commercial ports to support its growing operations overseas. Over the course of deploying 34 escort task forces (ETF) since 2008 to perform an anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, the PLAN has developed a pattern of procuring commercial husbanding services for fuel and supplies at hundreds of ports across the globe. -

From Micro to Macro: Italian Designers in South China the Italian Pavilion: Possibilities of Design

II Shenzhen Design Week From Micro to Macro: Italian designers in South China The Italian Pavilion: Possibilities of Design April 20 – May 4 , 2018 Can a spoon and a city have something in common? Italy will be the Country of Honor during the 2nd edition of the Shenzhen Design Week (SZDW). Sponsored by the Municipality of Shenzhen, the SZDW, due to thematic breadth and quality of the submitted projects, is considered one of the most important events organized in China in the field of design. The Italian participation will develop throughout the Week with seminars and workshops, and it will take the form of a Pavilion, especially designed by the members of an Association based in Shenzhen - Italian Designers Association (IDA) – and curated by the Department of Architecture and Design of Turin Polytechnic. The event is promoted by the Consulate General of Italy in Guangzhou, and supported by Shenzhen City of Design Promotion Association, in partnership with NABA-New Academy of Fine Arts, Domus Academy, with the sponsorship of Taramelli Group. The Italian Pavilion will be hosted in Sea World Culture and Arts Center / Design Society Shenzhen UCCN (UNESCO Creative Cities Network) Exchange Center. The national installation, called "From Micro to Macro: Italian Designers in South China", will remain open from April 20th to May 4th, and it will showcase the work of young Italian professionals based in the Pearl River Delta. The focus will be on the projects of the members of Italian Designers Association (IDA) and the 'South China- Turin Collaboration Lab', born from the cooperation of Turin Polytechnic with the prestigious South China University of Technology (SCUT). -

2016 Tengchong- L&A Design Star “Creative Village” International

2016 Tengchong- L&A Design Star “Creative Village” International University Student Design Competition in Hehua Resort Area Click to Register Today! 1. About “Creative Village” Tengchong, southwest of Yunnan Province, is well known in domestic and abroad for its rich natural resources like volcanic, Atami and Heshun town. The historical and cultural city on the Silk Road is an important gateway for China to South Asia and Southeast Asia, which is also the most popular tourist destination for visitors. Relying on the innate good natural environment, abundant tourism resources, profound cultural historical heritage, the current 2016 Tengchong-L&A Design Star "Creative Village" international competition use Hehua Dai and Wa Ethnic Township, southwest of Tengchong city, as the design field. In this way, we want to explore a consolidation pattern of cultural and creative tourism, rural construction and industrial heritage in the new era. We hope to increase added value in tourism product by promote the popularity of the town, and change the traditional development mode through reasonable scenic area planning and design. In addition to the magnificent ground water and underground river resources, constant perennial water with low temperature "Bapai Giant Hot Springs ", Hehua town also has Hehua Sugar Factory as industrial heritage constructed in 1983 and a rural settlement called Ba Pai village with rich humanistic resources. Students all over the world will work together to integrate and promote the high quality resources of field in three months. And finally make the scheme a new type of tourism destination solution based on southwest and facing the world. This international design competition is open to all university students both domestic and abroad, aiming to formulate creative strategies from a global perspective for the transformation of beautiful Chinese villages. -

Secondary Staff Bios 2018-19

Meet Our Secondary Team Amy Atkinson Jamie Bacigalupo Aaron Brice Middle and High High School & IB High School School & IB Art English Science & IB Chemistry Canada United States United States 11 years in 13 years in 14 years in education education education Education: B.A., University of Toronto; Education: B.A. in English Education, Education: B.S. in Bioengineering, Rice GradDipEd, University of Gustavus Adolphus College; University Wollongong; M.A., University of Master's in Curriculum and San Francisco Instruction, St. Catherine's Other Schools: North Miami High School, College Journeys School, Idyllwild Arts Other Schools: St. Joseph’s, Hong Kong; Barrie Academy, United States; Central, Canada; Serangoon Other Schools: Aurora Central, Jefferson Guangya IB School, China; Gardens, Singapore; ISE, Bloomington, United States; American School of Belo Thailand; Yew Chung Colegio Americano, Ecuador Horizonte, Brazil International School, China Paula Brunning Edwin Bywater YiTing Cao High School IB Math & IB Middle and High Counselor Physics School & IB Mandarin Canada United States China 21 years in 13 years in 8 years in education education education Education: B.A. in Psychology and Spanish, Education: B.S. in Chemical Engineering, Education: Bachelor’s Degree, Beijing Trent University; B.Ed., Queen's B.S. in Physics Education, Normal University; M.Ed., University; Master’s of Social Brigham Young University; M.S. University of Hong Kong Science in Counselling, in Multidisciplinary Studies, University of South Australia SUNY, Buffalo Other Schools: Other Schools: Qatar Academy Doha, HBKU Other Schools: Singapore American School, Student Services, Qatar; Singapore; American School of SACAC, Singapore; Lorna Doha, Qatar Whiston Study Center, Singapore Rachel Chen Hannah Codling Vanessa Coetzee Middle and High Middle School Middle and High School & IB Math School & IB Music Mandarin China United Kingdom South Africa 18 years in 20 years in 18 years in education education education Education: B.A. -

2018 APSN Newsletter I

Issue 26, No. 25/2018 2018 APSN Newsletter I March, 2018 CONTENTS APSN News 1st President Meeting 2018 GPAS Workshop Programme (updated) GPAS 2017 Winners APEC News Industry News Upcoming APSN & Maritime Events 1st President Meeting The 1st President Meeting of the APSN was successfully held on 17-19 January, 2018 in Kunming, China. The meeting confirmed the date, venue, title and theme of 2018 key activities: Date and Venue •November 13-16, 2018 •Singapore Key Activities: •Title: Port Connectivity Forum and the 11th Council Meeting of APSN •Theme: Port Connectivity: Positioning Asia-Pacific Ports for the Future •APSN 10th Anniversary Celebration •GPAS 2017 & 2018 Awarding Ceremony Details please refer to: http://www.apecpsn.o rg/index.php?s=/New s/detail/clickType/aps nNews/id/816 2018 GPAS Workshop Programme (updated) Look forward to meeting you in Beijing! GPAS 2017 Winners Bintulu Port, Malaysia Chiwan Container Terminal Co., Ltd, China PSA Singapore, Singapore Johor Port Authority, Malaysia Port of Batangas, The Philippines Shekou Container Terminals Ltd, China Tan Cang Cat Lai Port, Viet Nam Details please refer to: http://www.apecpsn.org/index.php?s=/News/detail/clickType/apsnNews/id/817 Bintulu Port , Malaysia Bintulu Port began its operations on 1st January 1983. It is the largest and most efficient transport and distribution center in the Brunei Darussalam-Indonesia- Malaysia- Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA) region. Bintulu Port is an international port which is strategically located in North-East Sarawak along the route between the Far East and Europe. Bintulu Port is the main gateway for export of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Malaysia. -

Shenzhen Shuttle Bus Service & Schedule

Shenzhen Shuttle Bus Service & Schedule Routing A) To and from Futian port and Shenfubao Building/Jiafu Plaza B) To and from Huanggang port and Shenfubao Building/Jiafu Plaza C) To and from Futian port and Animation City (Nanyou office) D) To and from Shenzhen Bay and Animation City (Nanyou office) E) To and from Shenfubao and Jiafu Plaza Pick up and drop off location Futian the parking lot for coaches at the adjacent corner of Gui Hua Road (桂花路) and Guo Hua Road (國花路) Huanggang Pick up point: Huanggang Coach Station(皇岗汽车站). The parking lot close to taxi stand Drop off point: Huanggang Customs Exit Hall Shenfubao Annex Bldg., Shenfubao Building, 8, Ronghua Road Jiafu Plaza Road side of Jiafu office main entrance Shenzhen Bay the parking lot for coaches towards the end of Shenzhen Bay exit Day of Service Monday to Friday (excludes China public holiday) Booking Not required. Services will be provided on a first come first serve basis. Arrangement - LiFung company logo will be shown on the shuttle bus - LiFung colleagues are requested to present staff card when boarding the shuttle Remarks - For enquiry of shuttle bus service, you may contact the following CS colleagues: Lucie Feng: 86 755 82856895 Kevin Long: 86 755 82856903 Photo of Shuttle Buses (Right side for Huanggang route only) Schedule Refer to the next 4 pages Route A1 - Futian Custom (Lok Ma Chau) → Shen Fu Bao → JiaFu Plaza (Every 10 minutes from 0830 to 1000) 0830 0920 0840 0930 0850 0940 0900 0950 0910 1000 Route A2 - Shen Fu Bao → JiaFu Plaza → Futian Custom (Lok Ma Chau) -

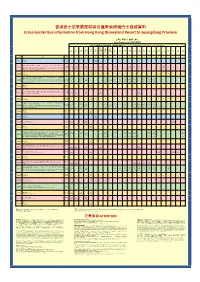

香港迪士尼樂園度假區往廣東省跨境巴士路線資料cross-Border Bus

香港迪士尼樂園度假區往廣東省跨境巴士路線資料 Cross-border Bus information from Hong Kong Disneyland Resort to Guangdong Province 票價(港幣/人民幣單程) Fares (Single-way in HKD/RMB) 車票只限以港幣/人民幣現金支付,有關價格請參閱下表。 We accept HKD & RMB cash only (all fares as shown below). 深圳 世界之窗 深圳 深圳灣 皇崗 (地鐵站) 高鐵北站 深圳 深圳灣 文錦渡 體育中心 廣州 番禺 佛山 口岸 Shenzhen Shenzhen 機場 台山 花都 新會 順德 中山 開平 東莞 常平 長安 江門 清遠 珠海 拱北 增城 Shenzhen 口岸 Shenzhen Guangzhou Panyu Foshan Huangang Window of North Shenzhen Taishan Huadu Xinhui Shunde Zhongshan Kaiping Dongguan Changping Chang’an Jiangmen Qingyuan Zhuhai Gongbei Zengcheng Bay Man Kam To Bay Sports Port The World Railway Airport Center (Metro Station Station) 發車時間 目的地 營運商 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ Departure Time Destinations Operators 華通巴士 文錦渡口岸 ZGHT 100 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 11:45 Man Kam To Sinoway (¥80) Bus 深圳灣、深圳世界之窗(地鐵站)、深圳機場、廣州、番禺(市橋、祈福新邨、碧桂園﹚、江門、新會 、中山 中旅汽車 170 170 100 120 160 190 170 190 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 12:30 Shenzhen Bay / Shenzhen Window of The World (Metro Station) / Shenzhen Airport / Guangzhou / Panyu (Shiqiao / CTT (¥130) (¥130) (¥80) (¥100) (¥150) (¥160) (¥130) (¥160) Clifford Estate / Country Garden) / Jiangmen / Xinhui / Zhongshan 皇崗口岸 永東巴士* 100 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 12:45 Huanggang Port EE Bus (¥100) 深圳灣、深圳灣體育中心、深圳機場、花都、新會、開平、東莞南城、佛山、廣州(天河城﹑花園酒店﹑廣 120 120 140 120 180 130 150 130 170 120 120 州賓館﹚、常平、順德、深圳高鐵北站、台山 環島旅運 (¥110) (¥110) 100 (¥135) -

Guangshen Railway Company Limited Annual Report 2002

annual report 2002 Guangshen Railway Company Limited Guangshen Railway Company Limited Annual Report 2002 Annual Report Guangshen Railway Company Limited 2002 CONTENTS Company Profile 2 Financial Highlights 4 Chairman’s Statement 5 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 11 Report of Directors 24 Report of the Supervisory Committee 35 Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 37 Corporate Information 41 Notice of Annual General Meeting 44 Auditors’ Report 46 Consolidated Income Statement 47 Consolidated Balance Sheet 48 Balance Sheet 49 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 50 Statements of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity 51 Notes to the Financial Statements 52 Financial Summary 93 Supplementary Financial Information 95 COMPANY PROFILE On 6 March, 1996, Guangshen Railway Company Limited (the “Company”) was registered and established in Shenzhen, the People’s Republic of China (the “PRC”) in accordance with the Company Law of the PRC. In May 1996, the H shares (“H Shares”) and American Depositary Shares (“ADSs”) issued by the Company were listed on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Hong Kong Exchange”) and the New York Stock Exchange, Inc. (“New York Stock Exchange”), respectively. The Company is currently the only enterprise engaging in the PRC railway transportation industry with its shares listed overseas. The Company is mainly engaged in railway passenger and freight transportation businesses between Guangzhou and Shenzhen and certain long-distance passenger transportation services. The Company also cooperates with Kowloon-Canton Railway Corporation (“KCR”) in Hong Kong in operating the Hong Kong through-train passenger service between Guangzhou and Kowloon. The Company provides consolidated services relating to railway facilities and technology. The Company also engages in commercial trading and other businesses that are consistent with the Company’s overall business strategy. -

The Transition of Urban Growth in China

The Transition of Urban Growth in China A Case study of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone by Mingzheng Gao Bachelor of Science in Architecture Harbin Institute of Architecture and Engineering Harbin, P. R. China July 1987 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 1995 (c)Mingzheng Gao 1995. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of the author Mingzheng Gao' Department of Architecture May 10, 1995 Certified by Michael Dennis Professor of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by .ASS.IV6AGHUSETTS INSTITUTE Roy Strickland OF TECHNOLOGY Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students JUL 251995 LIBRARIES - The Transition of Urban Growth in China A Case study of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone by Mingzheng Gao Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 12, 1995 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT The Chinese government announced new economic reform policies in December of 1978. The announcement included an urban distribution policy that emphasized small cities and towns for rural urbanization as a means to achieve modernization in China. This distribution policy called for limited development in large metropolitan areas, selective development of only a few medium-sized cities, and more development in small cities and towns. Until now, the urbanization and development of small cities and towns have been the most dramatic changes; however, the issue is how a small city can grow in a proper way, fitting to its geographical, social and economical development requirements. -

Taking Account of Both Physical and Virtual Spaces in Public Libraries

Breaking down Barriers between Physical and Virtual Spaces in Public Libraries -- Leading Practices in Guangdong Province of China Liu Honghui and Huang Qunqing Sun Yat-sen Library of Guangdong Province 213 Wenming Road, Guangzhou 510110, China Abstract The future of public libraries seems foreseeable through leading practices in Guangdong Province, of which the economy development is first ranked and Internet popularity third ranked nationwide. In new buildings, computers are placed in traditional reading rooms together with print collections. On websites, virtual visitors are able to enjoy lectures or exhibitions happening in physical spaces. In Microblog or WeChat communities, netizens not visiting library websites can also be informed. We find that barriers between physical and virtual spaces have been broken down; most of the resources and activities could be accessed by users inside or outside the library. Introduction According to a report published in early 2013, the economic gross in Guangdong Province has been ranked the first for 24 years continuously among all provinces nationwide [1]. Favored from financial support of the government, public libraries in Guangdong Province have been taking leading achievement in both physical spaces and virtual spaces. For physical spaces, many public libraries have opened their new buildings in recent ten years, such as new Dongguan Library opened in 2005, new Shenzhen Library opened in 2006, new Guangzhou Library opened in 2012 and new Foshan Library opened in 2014. Facilities in these new buildings have been updated into new concept furniture, multimedia reading computers, self-service terminals, WiFi, air-conditioned, cultural decorations and green plants, as well as functional rooms for exhibitions, lectures, performance, training or class, etc. -

China's Technology Mega-City an Introduction to Shenzhen

AN INTRODUCTION TO SHENZHEN: CHINA’S TECHNOLOGY MEGA-CITY Eric Kraeutler Shaobin Zhu Yalei Sun May 18, 2020 © 2020 Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP SECTION 01 SHENZHEN: THE FIRST FOUR DECADES Shenzhen Then and Now Shenzhen 1979 Shenzhen 2020 https://www.chinadiscovery.com/shenzhen-tours/shenzhen-visa-on- arrival.html 3 Deng Xiaoping: The Grand Engineer of Reform “There was an old man/Who drew a circle/by the South China Sea.” - “The Story of Spring,” Patriotic Chinese song 4 Where is Shenzhen? • On the Southern tip of Central China • In the south of Guangdong Province • North of Hong Kong • Along the East Bank of the Pearl River 5 Shenzhen: Growth and Development • 1979: Shenzhen officially became a City; following the administrative boundaries of Bao’an County. • 1980: Shenzhen established as China’s first Special Economic Zone (SEZ). – Separated into two territories, Shenzhen SEZ to the south, Shenzhen Bao-an County to the North. – Initially, SEZs were separated from China by secondary military patrolled borders. • 2010: Chinese State Council dissolved the “second line”; expanded Shenzhen SEZ to include all districts. • 2010: Shenzhen Stock Exchange founded. • 2019: The Central Government announced plans for additional reforms and an expanded SEZ. 6 Shenzhen’s Special Economic Zone (2010) 2010: Shenzhen SEZ expanded to include all districts. 7 Regulations of the Special Economic Zone • Created an experimental ground for the practice of market capitalism within a community guided by the ideals of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” •