A Walk Around Silverton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parents' Guide to Education in Shropshire 2021/22

Parents’ Guide to Education in Shropshire 2021/22 Closing Date: PRIMARY applications 15 January 2021 Closing Date: SECONDARY applications 31 October 2020 Apply online at www.shropshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions Apply online at www.shropshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions Apply online at www.shropshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions Apply online at www.shropshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Making an Application ......................................................................................................................... 5 Early Years The Application Process ....................................................................................................................... 6 Early Education..................................................................................................................................... 7 Primary Schools .................................................................................................................................... 9 Primary Oversubscription Criteria for Shropshire Community & Voluntary Controlled Primary Schools ...... 12 Admissions Flow Chart – Primary ...................................................................................................... 14 Oversubscription Criteria for Own Admission Authority Primary Schools ........................................ 15 Maps and Lists of Primary Schools in Shropshire ............................................................................. -

Town Guide 2020

FREE SHREWSBURY TOWN GUIDE 2020 originalshrewsbury.co.uk Top - bottom: Theatre Severn, Wyle Cop, Charles Darwin and Mary Webb statues in School Gardens, Butcher Row, The Square, Quarry Park, St Chad’s Church, Sabrina Boat. WELCOME Shrewsbury loves people and we hope the feeling is Arrive 5 mutual. You can easily explore the town centre on foot, bike or boat and discover plenty along the way. It’s Discover 7 not just a place full of flowers, medieval passages and café culture, Shrewsbury is packed with independent Eat 11 and national shops, restaurants and bars as well as must-visit international festivals. Drink 15 If you need more information call the Visitor Shop 19 Information Centre on 01743 258888, pop into it’s office in the Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery or ask Map 24 one of the Shrewsbury Ambassadors you’ll see around town from Easter until August . Events 27 YOU CAN’T COPY SHREWSBURY Explore 29 Do 33 Enjoy 36 Roam 39 48 Hours 42 Stay 45 For more information visit orginalshrewsbury.co.uk & visitshropshire.co.uk ORIGINAL SHREWSBURY AMBASSADORS From 11th April until late September visitors to Shrewsbury can discover the full range of what the town has to offer thanks to our team of Ambassadors. The Ambassadors, introduced in 2019, work alongside the Shrewsbury Town Guides and help visitors discover the hidden gems in the town. Ambassadors are on duty on them at points throughout the town Saturdays and Sundays from 10am and they can be spotted wearing to 2pm. Their aim is provide a better their bright blue tops and a experience for visitors and to help welcoming smile! them make the most of all that You can also volunteer by going to the Shrewsbury has to offer. -

Walking with Offa 15 GETTING THERE: You Can Find Public Transport Options Walking Food, Drink and Throughout Shropshire At: Accommodation

RATLINGHOPE | Darnford Valley RATLINGHOPE | Darnford Valley RATLINGHOPE | Darnford Valley Walking with Offa 15 GETTING THERE: You can find public transport options Walking Food, drink and throughout Shropshire at: accommodation www.travelshropshire.co.uk. 15 Imagine patrolling Or contact Traveline on 08712 002233. with Offa the border without BY BUS: The Bridges is served by the Long Mynd & a decent pub. How Stiperstones Shuttle bus which runs at weekends and would Offa’s Dyke Bank Holidays from April to September. The shuttle have been built runs from Church Stretton to numerous points in the Shropshire Hills. You can link to the scheduled services A Golden Valley without them? between Shrewsbury and Ludlow (435) at Church Over a thousand Stretton. Further information on in the foothills of years later, keep up www.shropshirehillsshuttles.co.uk and the tradition and www.travelshropshire.co.uk the Long Mynd stop for a drink BY RAIL: There is a mainline station at Church Stretton. and a bite to eat BY CAR: Car parking is available at The Bridges, A 6½ mile walk with a steady climb at The Bridges, Ratlinghope SY5 0ST. Ratlinghope. beside the Darnford Brook and along Sample the real ales at the tap house of the Three To get the best from your walk we recommend an ancient drovers road Tuns Brewery, the oldest in the country. The Bridges comfortable walking boots, waterproof jacket and overtrousers, warm clothing, gloves and warm hat or taking 2 to 3 hours occupies an idyllic location beside the River Onny. sun cream and sun hat (depending on the season!), a A wide selection of soft drinks and hot drinks mobile phone and something to eat and drink. -

Old Houses Shrewsbury

Old H ou se s Sh rewsbu ry THEIR HISTORY AND ASSOCIATIONS . O R H . E F R EST , Val l e lu o . c Ca mdoc a nd S r n l d b H n S e . eve y C , “ ’ ‘ A uthor o the Fa una o Nor th W a les F a un a o S ho slz z re etc . f f ' f p , 1 1 9 1 . W S on m e e e . ilding , Li it d , Print rs , Shr wsbury P R E F A C E . LTHOUGH many books dealing with the history or 2 topography of Shrewsbury have appeared from time m work t o to ti e , no devoted the history of its old I houses has hitherto been published . n the present volume I h a ve tried to give a succinct a ccount of these in terestin g — ’ old buildings Shrewsbury s most a ttractive feature l a m partly by co lating all available dat regarding the , and partly by careful study and comparison of the structures themselves . The principal sources of information as to their past ’ history are Owen an d Bl akeway s monument a l History of S hrewsbur y , especially the numerous footnotes therein the Tra n sa ction s of the S hropshir e A r chwol ogica l S oc iety in clud ’ n d Bl k M S . a a ewa s ing the famous Taylor . y Topo ’ graphical History oi Shrewsbury Owen s A c coun t of S hrewsbury published an onymously in 1 80 8 S hropshir e Notes a n d Quer ies reprinted from the Shrewsbury Chr on i cle and S hr eds a n d P a tches a similar series of earlier ’ ’ date from Eddowes Journal . -

Salopian Recorder No.92

Diary Dates The newsletter of the Friends of Shropshire Archives, Saturday 20 October 2018 Saturday 17 November 2018 ARCHIVES First World War Showcase Day Much Wenlock Charter Celebrations SHROPSHIRE gateway to the history of Shropshire and Telford 10.00am - 4.00pm Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Contact Much Wenlock Town Council Shrewsbury SY2 6ND www.muchwenlock-tc.gov.uk Free event! Saturday 27 October 2018 Saturday 24 November 2018 Arthur Allwood, Victoria County History Annual lecture Friends Annual Lecture Shropshire RHA and Horses in Early Modern Shropshire: for Dr Kate Croft - “Healthy and Expedient”: Childcare and KSLI, 1912-1919 Charity at the Shrewsbury Foundling Hospital 1759-1772 Service, for Pleasure, for Power? Page 2 Professor Peter Edwards 10.30am, £5 Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury, SY1 2AQ 2.00pm, £5 donation requested For further details see www. Reasearching Central, Shrewsbury Baptist Church, 4 Claremont friendsofshropshirearchives.org.uk Street, Shrewsbury Myndtown Church Page 5 Tuesday 6 November 2018 Tuesdays, 22 January – 26 February 2019 Discover the Stories Behind the Stones House History Course Shrewsbury at work The Beautiful Burial Ground project is offering a FREE Contact [email protected] for training session at Shropshire Archives for those further details interested in the stories told by our burial grounds. Page 8 This session will cover an introduction to the archive as well as how to use the archive to investigate the lives and stories in your local burial ground. To book your free place please get in touch with George at [email protected] or 01588 673041 10.30am - 12.30pm ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The newsletter of the Friends of News Extra.. -

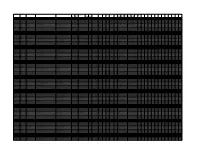

Organisation Name Organisation Code Contract

Organisation Name Organisation Code Contract Reference number / Title of the agreement Local Authority Department Responsible Service Service/D Description of Goods Procurem Procurem Start Date End Date Review Extension Contract Irrecover Supplier Supplier Supplier Nominate Pre- GeoArea GeoArea ID Categoris ivision and Services ent ent Date Period Amount able (Beneficia (Beneficia (Beneficia d contact contractu Label URI ation Code (Merchan (Merchan VAT ry) Name ry) ID ry) Type point al Process ) ) Ud Shropshire Council 00GG ROC019 Investment Management Advice Treasury & Pensions Services Central Services - TradInvestment Management Advice 201801 01/04/1997 01/08/2012 LEGAL & GENERAL INVESTMENT [email protected] Shropshire Council 00GG RMC075 Operating Lease - Mobile Library/Stackers/Vehicles Programme & Contracts Highways and TranspoOperating Lease - Mobile Library/ 381600 31/03/2001 01/03/2012 305,000.00 ILC [email protected] Shropshire Council 00GG CMC003 Preventative services for older people Adult Social Care Delivery Adult Social Care - OldPreventative services for older peo321000 01/10/2001 31/03/2011 2,500,000.00 AGE CONCERN [email protected] Shropshire Council 00GG RMC079 Operating Lease - Vehicles Programme & Contracts Highways and TranspoOperating Lease - Vehicles 381600 01/04/2002 01/04/2012 176,000.00 ILC [email protected] Shropshire Council 00GG ROC031 Operating Lease - Vehicles Programme & Contracts Highways and TranspoOperating Lease - Vehicles 381600 01/04/2003 01/06/2011 -

'Tradition and Rural Modernity in Mary Webb's

‘Tradition and Rural Modernity in Mary Webb’s Shropshire: Precious Bane in Context’ Simon J. White, Oxford Brookes University & Owen Davies, University of Hertfordshire1 Precious Bane (1924), which won the Prix Femina Vie Heureuse prize on its publication in 1924, is set in rural Shropshire at the beginning of the nineteenth century. It straddles the end of the Napoleonic wars and tells the story of Prue Sarn who was born with a cleft-lip and is believed to be a witch by many in the local community, and her brother Gideon, who is determined to re-establish the family farm on a more profitable basis following the sudden death of their father. The story of Gideon and Prue intersects with that of the local cunning-man Beguildy, with whom the Sarn family have a long-running feud. Beguildy disapproves of relationship between Gideon and his daughter Jancis, and the fall-out from their betrothal has tragic consequences for everyone involved. The novel challenges the post-Enlightenment hierarchical opposition between a supposedly enlightened modernity, and the allegedly ignorant superstition of those whose lives are still structured around traditional ways of understanding the world.2 This distinction has often been central to the promotion of what Karl Bell calls the ‘mythification of the modern.’ (119) Bell has in mind the uncritical assumption that all things modern are a source of progress, especially when, as is often the case, the modern is understood to mean a world dominated and structured by instrumentalism and laissez faire capitalism. In the foreword to Precious Bane, Webb remarked of country life, ‘there is a permanence, a continuity […] which makes the lapse of centuries seem of little moment’ (6). -

Programme in Developmentv5 Addedad

Shropshire LGBT History Month www.shrewsburyLGBThistory.org.uk Welcome to Back in Time 3 February 2018 Having had 2 fantastic Weekend Festivals in 2016 and 2017, this one is a bit different. Instead of one weekend packed full of LGBT Heritage, we thought a whole month would be better! And - instead of doing most of the organising ourselves, for 2018 we have invited others to put their LGBT History events into one programme, illustrating the breadth of activity and offering a wide choice for us all to engage with. Events also take place in a variety of locations and we’re delighted to include Oswestry and Telford in this brochure. We think that everyone has risen to the challenge and hope that you agree. This brochure includes presentations, workshops, performance, films and more. Each has its own booking method and they vary in price - if indeed there is any charge at all. We hope that everyone will support these events whole-heartedly and enjoy this very special Shropshire LGBT History Month - and encourage your friends, neighbours and family to come along and join in. For full details, late runners which missed this brochure and all links to booking tickets (where that is necessary) are on the website: www.shrewsburyLGBThistory.org.uk In association with Have a fantastic February The Salopian Rainbows [email protected] Shrewsbury LGBT History Festival was ‘adopted’ by SAND (Safe Ageing No Discrimination) in April 2016 and operates as a SAND Project with its own steering group [calling themselves The Salopian Rainbows], and bank account. All organisers work voluntarily. -

SNL 7 1 S Pring 1 1

Shropshire Archaeological SHROPSHIRE and Historical ARCHAEOLOGY & HISTORY Society NEWSLETTER No. 71, Spring 2011 Website: http://www.shropshirearchaeology.org.uk Newsletter Editor: Hugh Hannaford, Archaeology Service, Historic Environment Team, Shirehall, Shrewsbury, SY2 6ND Membership Secretary: William Hodges, Westlegate, Mousecroft Lane, Shrewsbury, SY3 9DX SOCIETY NEWS The site is hosted within the Discovering AGM: The ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING of Shropshire’s History website - the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical http://www.shropshirehistory.org.uk/ You Society will be held at the Shirehall, can find details of all the Society’s events and Shrewsbury, on Saturday 9th April 2010 at publications on our site, as well as links to a 9.00am. The AGM will be followed at 10.20am wealth of information about Shropshire’s by The Dark Ages in Shropshire Dayschool. archaeology, history, and landscape. If you Dark Age Day School – Now fully booked. have any suggestions for content on our pages, Many apologies to all the members who were please contact me, preferably by email at: unable to get a place at the Dark Age day [email protected] school. This has proved far more popular than or by phone on: 01743 252575 we imagined, to the extent that we reached the Hugh Hannaford maximum capacity of the Shirehall a month before the meeting. By contrast, the previous Circulation of newsletter etc.. If you would two day schools that we have organised had like to receive the AGM papers and Newsletter places available for those who turned -

Some Context 1885 Ageing Offence of “Gross Indecency” Created, Making All Sexual Acts Between Men Illegal

Some context 1885 Ageing Offence of “gross indecency” created, making all sexual acts between men illegal. Who we are, what we feel and how we act in our 1895 Oscar Wilde prosecuted for gross indecency and sentenced to two present life is all based on our past. years in prison. 1933 If the past includes experience of prejudice, Nazis round up homosexuals and send them to the concentration discrimination, criminalisation, harassment – camps. Gay men have to wear a pink triangle on their camp clothes. this is bound to have an impact on how we see 1954 ourselves as older people and how open we are Alan Turing commits suicide, 18 months after being given a choice with others. between two years in prison or libido-reducing hormone treatment for a year as a punishment for homosexuality. ‘Before the Act’ started around 1998, 1957 becoming the Older Gay men’s Group, Wolfenden committee recommends the decriminalisation of gay meeting in the Gay Men’s Health Project sex between consenting adults over 21, except in the armed forces. offices until 2001, moving from there to Belmont in 2003 and then supported by 1967 Age Concern (AgeUK) up until recently Gay sex decriminalised, with new privacy clause - no act may take when it has temporarily closed. place where a third party is likely to be present. Age of consent set at 21 (compared to 16 for heterosexuals and lesbians). Several events were held in 2008 showing Gateway to Heaven – a powerful and often humorous performance based entirely on the memories of older lesbians and gay As well as the serious stuff, men, collected by writer and lesbian we have fun and attend comedian Clare Summerskill. -

Route 15 Thresholds to Bayston Hill

Route 15 Thresholds to Bayston Hill Illustration of Cooks Cottage, Blakemoorgate Discover Shropshire Walking from the end of the Wilderley Hall collection of military tanks, a deer farm Long Mynd to the outskirts of and even old rope. The bumpy old As you walk down from the hills past Shrewsbury will take you from the lane that runs along its crest is called Sheppen Fields with its 15th century wild ruggedness of the Bronze the rope walk and here 300 years ago long house admiring the views you Age cairns, Iron Age forts and the flax and hemp ropes that kept will come across Wilderley Hall with ancient high drovers’ roads of the ships sailing and mines hauling were its small but impressive Norman twisted together. Shropshire hills to the gentler Motte and Bailey. Wilderley means farmland of Norman times. “the clearing belonging to Wilfred”, Perhaps all this inspired its most I wonder if that was the first person famous resident; Mary Webb who to build here but was he Norman or wrote Precious Bane and gone to Forget the high hilltops and moors Saxon? Nobody is sure. earth. as you walk downhill to the north: Here the maps change and the word “fort” is seen less and less being Lyth Hill Country Park Bayston Hill replaced by “Motte and Bailey”. The There is one gem to come on the walk The last town before Shrewsbury with names also cry out the changes towards Shrewsbury, a little wooded a name that means “The hill on which with Wilderley halls, Netley Hall and hill that’s now a Country Park, on the stands Baegas stone” is now a large Underhill Hall appearing, all signs of map it’s doesn’t look spectacular but housing estate here once stood a large our Norman past. -

William Hazledine, Shropshire Ironmaster and Millwright

WILLIAM HAZLEDINE, SHROPSHIRE IRONMASTER AND MILLWRIGHT: A RECONSTRUCTION OF HIS LIFE, AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF ENGINEERING, 1780 - 1840 by ANDREW PATTISON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Ironbridge Institute Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity, College of Arts and Law, University of Birmingham October 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The name of William Hazledine (1763 – 1840) is almost unknown, even to industrial historians. This is surprising, since he provided the ironwork for five world ‘firsts’, and he was described at the time of his death as ‘the first [foremost] practical man in Europe’. The five structures are Ditherington Flax Mill, Shrewsbury (the first iron- framed building in the world), Pontcysyllte Aqueduct (still one of the longest and highest in Britain), lock gates on the Caledonian Canal, a new genre of cast-iron arch bridges, and Menai Suspension Bridge. This thesis aims to rediscover Hazledine’s life and work, and place it in the context of social and industrial history. It particularly concentrates on the development of cast iron technology in Shropshire, which has been less studied than the work of earlier ironmasters, such as the Darbys and John Wilkinson.