Klamath Marsh National Wildlife Refuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release

United States Department of Agriculture Umpqua National Forest Burned Area Emergency Response Summary – Thielsen Fire October 22, 2020 The Thielsen Fire was detected on September 8, 2020 at approximately 8:30 a.m. after lightning passed through the area. The fire was on the Diamond Ranger District of the Umpqua National Forest, approximately 5 miles north of Crater Lake National Park. It burned within one mile of the Diamond Lake Resort, along both sides of Oregon Highway 138, and a small portion of the Mount Thielsen Wilderness. The fire (as of 10/6/2020) encompassed 9,951 acres primarily in a mixed conifer forest. The fire burned a mosaic pattern through most of the area, and the majority burned with low and moderate severity. The Forest Service assembled a Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) team on September 26, 2020. This team of experts in soils, geology, hydrology, engineering, botany, recreation, archaeology, wildlife, fisheries, and GIS, began assessing the post-fire effects to critical values on Forest Service lands. BAER critical values include Life and Safety, Natural Resource, Cultural Resources and Property. The team developed a Soil Burn Severity (SBS) map to document the degree to which soil properties had changed within the burned area. Fire damaged soils have low strength, high root mortality, and increased rates of water runoff and erosion. Using the SBS map, BAER team members ran models to estimate changes in soil erosion, stream flows (hydrology) and debris flow (geology) potential. The models compared pre-fire conditions to predicted post- fire conditions to determine relative changes, which are then used to determine the relative risk to different critical values and recommendations to address those things determined to be an emergency. -

Shasta Rain Rock” by Gail L

F R JEFFERSON E E BACKROADS Come and be a Montague part of this amazing display Balloon of hot air balloons, held Fair each year in September in Sept. 24th - 26th Montague, California. Read a fun story about one of the past hot air balloon fairs on Page 6 and also see the advertisement for this year’s event on Page 13. Photo of magical hot air balloons by M. Fain What’s Inside . What it is . History of Yreka by Claudia A. East . .. Page 2 Welcome! We are happy to report that State of Jefferson Tourism Committee . Page 3 The Mythical State of Jefferson is most Discovering The State of Jefferson by Gail L. Jenner . Page 4 definitely alive and well. We bring Local Shoppe of the Month: Wildwood Crossing, Etna. Page 5 you stories, up-coming events, history Montague Balloon Fair . Page 6 and spotlight articles on the Mom & Four Volcanoes of The State of Jefferson . Page 7 Pop Shoppes, businesses, artists, musicians, inns, eateries, recreational Maps of The State of Jefferson & Siskiyou County. Page 8 opportunities and community What IS The State of Jefferson, You Ask?. Page 9 organizations proudly operating here Backpacking in Jefferson by Richard Platz . Pages 10-11 in the Heart of The State of Jefferson: Where to Go - What to See - When to Do It . Page 12 Rugged & Beautiful Siskiyou County. Farmers Markets in Siskiyou County . Page 13 Locally Owned & Operated Backroads Adventures by Ralph Fain . Pages 14-15 Ad Rates - Advertisers & Other Information . Page 16 SEPTEMBER 2010 Hit the Backroads! www.jeffersonbackroads.com 5417 93078 NL.indd 1 9/2/10 12:55 PM HISTORY OF YREKA: “Yreka’s Welcome Arch” by Claudia A. -

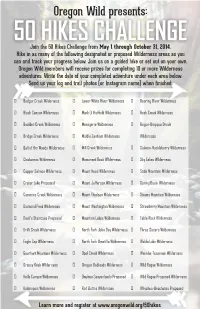

50 HIKES CHALLENGE Join the 50 Hikes Challenge from May 1 Through October 31, 2014

Oregon Wild presents: 50 HIKES CHALLENGE Join the 50 Hikes Challenge from May 1 through October 31, 2014. Hike in as many of the following designated or proposed Wilderness areas as you can and track your progress below. Join us on a guided hike or set out on your own. Oregon Wild members will receive prizes for completing 10 or more Wilderness adventures. Write the date of your completed adventure under each area below. Send us your log and trail photos (or Instagram name) when finished. � Badger Creek Wilderness � Lower White River Wilderness � Roaring River Wilderness � Black Canyon Wilderness � Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness � Rock Creek Wilderness � Boulder Creek Wilderness � Menagerie Wilderness � Rogue-Umpqua Divide � Bridge Creek Wilderness � Middle Santiam Wilderness Wilderness � Bull of the Woods Wilderness � Mill Creek Wilderness � Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness � Clackamas Wilderness � Monument Rock Wilderness � Sky Lakes Wilderness � Copper Salmon Wilderness � Mount Hood Wilderness � Soda Mountain Wilderness � Crater Lake Proposed � Mount Jefferson Wilderness � Spring Basin Wilderness � Cummins Creek Wilderness � Mount Thielsen Wilderness � Steens Mountain Wilderness � Diamond Peak Wilderness � Mount Washington Wilderness � Strawberry Mountain Wilderness � Devil’s Staircase Proposed � Mountain Lakes Wilderness � Table Rock Wilderness � Drift Creek Wilderness � North Fork John Day Wilderness � Three Sisters Wilderness � Eagle Cap Wilderness � North Fork Umatilla Wilderness � Waldo Lake Wilderness � Gearhart Mountain Wilderness � Opal Creek Wilderness � Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness � Grassy Knob Wilderness � Oregon Badlands Wilderness � Wild Rogue Wilderness � Hells Canyon Wilderness � Owyhee Canyonlands Proposed � Wild Rogue Proposed Wilderness � Kalmiopsis Wilderness � Red Buttes Wilderness � Whychus-Deschutes Proposed Learn more and register at www.oregonwild.org/50hikes. -

STEEL POINTS No

882 .C8 S81 JUN to tol *--AN"N4CCO - PORTLAND UWMAGELES P,Press PHIL. METSCHAN, PRES C. H. SHOLES, SEC'Y Clippings F. DRESSER, V. PRES CHAS. E. RUM ELI N. TRt A' WILL G. STEEL, MANAGER ARE MONEY MAKERS '~~R~~ For Contractors, Supply Houses, VF-;', ~~Business Men and Corporations If you know how to use them. If you don't know how, ring up PACIFIC 2034 and we will call and see you. Public Men and Politicians Let Us Read the Papers for You Allen Press Clipping Bureau 109 SECOND ST., PORTLAND, OREGON. 424. Lumber Exchange Telephone Main 3051 MOUNTAIN VIEW HOUSE Portland, Oregon 0. C. YOCUM. Guide City and Suburban Real Estatel MRS. A. M. YOCUM, Manager All Sorts of Real Property in Klamath Count,. 1 Board and Lodging, per day $1.50 Board and Lodging, per week - 8.oo Correspondence Solicited Board and Lodging, per month - 25.00 i, i Old' Government Camp, Mt. Hood i LIBRARY i -j-, EALMON P. 0. CLACKAMAS CO., OREGON WESTERN OREGON STATE COLI.!6E I M~ONMOUTH, OREGON 97361 . _. - - I - -1- -_ _-', - 1 - 1-1_,_-0__--i"- -_- I I W carried to them by the waters fromn the mountains, and have Slamath County. for ages been producing immense crops of tules, gigantic Klamath County, Oregon, is on the California state line bull-rushes, which grow six to twelve feet high, and so and just east of the Cascade range of mountains. It has a thick that it is almost impossible to get through them. population of about 7,000. -

Geology and Mineral Resource Potential Map of the Windigo

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geology and mineral resource potential map of the Windigo-Thielsen Roadless Area, Douglas and Klamath Counties, Oregon By David R. Sherrod, 1 o John R. Benham, and Norman S. MacLeod* Open-File Report 83-660 1-U.S. Geological Survey ^U.S. Bureau of Mines 1983 STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Under the provisions of the Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, Sept. 3, 1964) and related acts, the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines have been conducting mineral surveys of wilderness and primitive areas. Areas officially designated as "wilderness," "wild," or "canoe" when the act was passed were incorporated into the National Wilderness Preservation System and some of them are presently being studied. The act provided that areas under consideration for wilderness designation should be studied for suitability for incorporation into the Wilderness System. The mineral surveys constitute one aspect of the suitability studies. The act directs that the results of such surveys are to be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. This report discusses the results of a mineral survey of the Windigo-Thielsen Roadless Area (6132) in the Deschutes, Umpqua, and Winema National Forests, Douglas and Klamath Counties, Oregon. The Windigo-Thielsen Roadless Area was classified as a further planning area during the Second Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE II) by the U.S. Forest Service, January, 1979; part of the area was administratively endorsed as wilderness in April 1979. SUMMARY The Windigo-Thielsen Roadless Area has no identified metallic mineral resources and there is no evidence of a potential for their occurrence. -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

The ORE BIN Volume 28, No.9 September, 1966 FULGURITES FROM MOUNT THIELSEN, OREGON By William B. Purdom Southern Oregon College, Ashland, Oregon Fulgurites are natural glasses formed where lightning strikes bare rock or sand. They are the result of a very large electrical discharge between the earth and clouds. The potential difference necessary for such a discharge results when minute droplets of water condense on dust particles in the atmosphere. These droplets grow until the limit of cohesion is exceeded (when the drop has a diameter of about 4mm), after which they are torn apart by rapidly ascend ing air currents. The smaller, lighter fragments are carried to the top of the cloud, losing electrons as the result of friction. Thus the upper portion of the cloud becomes positively charged, and the lower portion negatively charged, and an electrical potential difference exists between the top and bottom of the cloud. The earth itself becomes charged by induction and the electrons in the earth become concentrated on any protuberances on the surface. If the electrical potential difference between oppositely charged por tions of the cloud or between the cloud and the earth become great enough, discharge occurs in the form of an immense spark. The critical potential difference is generally in the range of 20 to 30 million volts. It has recent ly been ascertained that these discharges occur in 10 microseconds or less (Orville, 1966). High-speed photographs reveal that the stroke starts as a thin leader passing between different parts of the cloud or between cloud and earth. -

The Neoglacial History of Mt. Thielsen, Southern Oregon Cascades

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 6-8-2001 The Neoglacial History of Mt. Thielsen, Southern Oregon Cascades Martin Dietrich Lafrenz Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geography Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lafrenz, Martin Dietrich, "The Neoglacial History of Mt. Thielsen, Southern Oregon Cascades" (2001). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2429. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2426 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Martin Dietrich Lafrenz for the Master of Science in Geography were presented June 8, 2001, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITIEE APPROVALS: Teresa L. Bulman Scott Burns Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: Teresa Bulman, Chair Department of Geography ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Martin Dietrich Lafrenz for the Master of Science in Geography presented June 8, 2001. Title: The Neoglacial History of Mt. Tbielsen, Southern Oregon Cascades. Little Ice Age (LIA) deposits are recognized on Mt. Tbielsen, southern Oregon Cascades (43° 9' N, 122° 3' W), based on particle morphology and relative position. The initial advance, Lathrop 1, created a sharp-crested moraine and a protalus rampart within 200 m of the headwall. The retreat of the glacier and recent ice movement, Lathrop 2, is recognized by the deformation of the moraine and a mantle of "protalus till" creating a polygenetic "push-deformation'' moraine. -

Historical Snowdepth Comparison Along the Cascade Range This Compilation Is ©2002-2005 Amar Andalkar

Page 1 of 5 Historical Snowdepth Comparison along the Cascade Range This compilation is ©2002-2005 Amar Andalkar www.skimountaineer.com Snowdepths in inches for the listed period of record, measured at snow courses, snow stakes, and automated gauges Data provided by: throughout the length of the Cascade Range. Note that snowfall data is available for only a few of these sites. BCRFC British Columbia River Forecast Centre NWAC Northwest Weather & Avalanche Center NRCS Natural Resources Conservation Service WRCC Western Regional Climate Center Updated through the 2003-2004 season. Italicized numbers are estimated based on limited available data. CCSS California Cooperative Snow Surveys NPS National Park Service See the end of the chart for an explanation of the Depth and Variability classification codes. WBSR Whistler Blackcomb Ski Resort ECNCA Environment Canada National Climate Archive BRITISH COLUMBIA Jan 1 Feb 1 Mar 1 Apr 1 May 1 Depth Variab 350 Bridge Glacier, N of Mt Meager (4600 ft) 350 Tenquille Lake, E of Mt Meager (5500 ft) Bridge Glacier (Lower) Average 47 61 65 69 61 Avg Snowfall — L LV 300 300 4600 ft (15 miles north of Mt Meager) Minimum 32 48 40 47 43 Max Snowfall — 250 250 BCRFC, monthly, 1995–present Maximum 63 88 117 108 87 Max Depth 117 (1999) 200 200 This fairly new measurement site is located at the eastern end of the Lillooet Icefield, in the next drainage north of the Mount Meager 171 150 150 Volcanic Complex. Snowdepths are relatively low but quite consistent due to its northerly location and icefield margin microclimate. -

Spring 2020 Volume 9, Issue 1 the Crater Chronicle

National Weather Service - Medford, Oregon Spring 2020 Volume 9, Issue 1 The Crater Chronicle Are We Headed Back Into Drought? Ryan Sandler, Warning Coordination Meteorologist s of early March, the 2019-20 water year has not been a good one and the outlook is not encouraging. There have been very few atmospheric river storm systems impacting the region this wet season and drought conditions were expanding across the West.A In southern Oregon and northern California, the water year which Inside This Issue began October 1st saw no drought designated across the region. However, by March 3rd all of southern Oregon and far northern California had abnor- Drought cont. 2 mally dry Cold Water Safety 3 to moder- Climate & Gardening 4-5 a t e d r o u g h t Eyes from Space—Satellites 6-7 conditions A Tale of Two Partner 8 ( r i g h t ) . Agencies On March About Us 9 9th, the southern O r e g o n snowpack r a n g e d Spring Began on from 63% to 69% of March 19th at n o r m a l . 8:49 pm PDT. Conditions were even worse in northern California where the Mount Shasta and McCloud areas had only 46 to 49% of normal snowpack. The spring outlook does not look promising with probabilities favoring warmer and drier than normal conditions so drought development is likely. Reservoir levels were running below normal and worsening. On March 9th, Lost Creek Reservoir was 14% below normal, and Applegate Lake was 24% below normal. -

Wilderness Areas Along the Pacific Crest Trail

Vancouver C A N A B D R I T I A S H C O Wilderness Areas L U M B MT BAKER- 1 I A OKANO G SNOQ 2 AN- UALMIE along the WE N ATCHEE NATIONAL 3 LO YMPIC NATIONAL NATIONAL FOREST Pacific Crest Trail FOREST Seattle 4 FOREST 5 50 years of Wilderness on the PCT W A S H I N On Sept. 3, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law, recognizing 7 6 G T O placesN “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself 8 GIFFORD PINCH is a visitor who does not remain.” O NATIONALT 9 FOREST Countless people have passed and will continue to pass through America’s most treasured land- 10 scapes, including the 48 wilderness areas that include the Pacific Crest Trail. 11 Portland The Wilderness Act established the National Wilderness Preservation System and set aside an 12 initial 9.1 million acres of wild lands for the use and benefit of the American people. Over the past MT HOOD 13 50 years, Congress has added more than 100 million acres to this unique land preservation system. NATIONAL FOREST To learn more about the country’s wilderness areas, visit www.wilderness.net. SIUSL A W NATIONAL FOREST O 1 Pasayten Wilderness – Oct. 2, 1968 R 14 E G 15 O N 2 Stephen Mather Wilderness – Nov. 16, 1988 (Wash. Park Wilderness Act of 1988) WILLAMETTE 16 NATIONAL DESCHUTES 3 Glacier Peak Wilderness – Sept. 3, 1964 (Wilderness Act) FOREST NATIONAL 4 Henry M. -

Biographical Memoir by Al E X a N D E R R

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES H O W EL WILLIAMS 1898—1980 A Biographical Memoir by AL E X A N D E R R. MCBIRNEY Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1991 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. HOWEL WILLIAMS October 12, 1898-January 12, 1980 BY ALEXANDER R. McBIRNEY T is NOT AN EXAGGERATION to say that Howel Williams, I through his own work and that of his students, was largely responsible for the emergence of volcanology as a rigorous branch of modern science. Few have left so pervasive an im- print on their fields; even fewer have inspired wider admi- ration or deeper affection. Less interested in the eruptive phenomena of active vol- canism than in broad structural and petrographic relations, he had a masterful ability to reconstruct the forms and his- tories of long-extinct volcanic provinces. It was his uncanny eye for landforms and the regional significance of lithologic relations that enabled him to synthesize the evolution of en- tire provinces from a few seasons of field reconnaissance and petrographic studies. EDUCATION AND CAREER Born in Liverpool, England, Howel Williams was raised along with his identical twin, David, and six other children in a modest middle-class household. He spoke only Welsh until the age of six. His father recognized young Howel's ability early and encouraged his intellectual ambitions. With the help of a series of awards and scholarships, he began the 395 396 BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS career that soon brought him international repute as one of the foremost igneous geologists of his time. -

Mount Thielsen Wilderness Air Quality Report, 2012

Mount Thielsen Wilderness Air Quality Report Wilderness ID: 226 Wilderness Name: Mount Thielsen Wilderness Mount Thielsen Wilderness Air Quality Report National Forest: Deschutes National Forest, Umpqua National Forest, Winema National Forest State: OR Counties: Douglas, Klamath General Location: Southern Oregon Cascade Range Acres: 54,914 Thursday, May 17, 2012 Page 1 of 4 Mount Thielsen Wilderness Air Quality Report Wilderness ID: 226 Wilderness Name: Mount Thielsen Wilderness Wilderness Categories Information Specific to this Wilderness Year Established 1984 Establishment Notes Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 Designation Clean Air Act Class 2 Administrative Deschutes National Forest, Fremont-Winema National Forest, Umpqua National Forest Unique Landscape Features Carved majestically by glacial activity and rising 9,182 feet to aspire-shaped summit referred to sometimes as the "Lightning Rod of the Cascades," Mount Thielsen anchors the southern portion of this Wilderness. To the south is Crater Lake National Park, and on the periphery is flat to moderately rolling country, which changes to very steep and sharply dissected ridges toward the crest of the Cascade Mountains. Timberline stands at about 7,200 feet, just above a forest of mountain hemlock and fir mixed with whitebark pine. Lodgepole pine dominates the vegetation lower down. Many streams carry a substantial amount of snowmelt in spring, giving rise to an abundance of early summer mosquitoes. A 34-mile segment of the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail crosses the Wilderness from Tolo Mountain in the north to near Summit Rock in the south. The Mount Thielsen Trail enters for approximately five miles from the west side to rise above the tree line and, after 200 feet of hand-over- hand scrambling, finally reaches to within 80 feet of the summit and a breathtaking view.