Namacurra E Maganja Da Costa Field Report Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jentzsch 2018 T

https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl License: Article 25fa pilot End User Agreement This publication is distributed under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act (Auteurswet) with explicit consent by the author. Dutch law entitles the maker of a short scientific work funded either wholly or partially by Dutch public funds to make that work publicly available for no consideration following a reasonable period of time after the work was first published, provided that clear reference is made to the source of the first publication of the work. This publication is distributed under The Association of Universities in the Netherlands (VSNU) ‘Article 25fa implementation’ pilot project. In this pilot research outputs of researchers employed by Dutch Universities that comply with the legal requirements of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act are distributed online and free of cost or other barriers in institutional repositories. Research outputs are distributed six months after their first online publication in the original published version and with proper attribution to the source of the original publication. You are permitted to download and use the publication for personal purposes. All rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyrights owner(s) of this work. Any use of the publication other than authorised under this licence or copyright law is prohibited. If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. -

Disasters, Climate Change and Human Mobility in Southern Africa: Consultation on the Draft Protection Agenda

DISASTERS, CLIMATE CHANGE AND HUMAN MOBILITY IN SOUTHERN AFRICA: CONSULTATION ON THE DRAFT PROTECTION AGENDA BACKGROUND PAPER South Africa Regional Consultation in cooperation with the Development and Rule of Law Programme (DROP) at Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch, South Africa, 4-5 June 2015 DISASTERS CLIMATE CHANGE AND DISPLACEMENT EVIDENCE FOR ACTION NORWEGIAN NRC REFUGEE COUNCIL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Southern Africa Consultation will be hosted by the Development and Rule of Law Programme (DROP) at Stellenbosch University in South Africa and co-organized in partnership with the Nansen Initiative Secretariat and the Norwegian Refugee Council. The project is funded by the European Union with the support of Norway and Switzerland Federal Department of Foreign Aairs FDFA CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Background to the Nansen Initiative Southern Africa Consultation ...............................................................................7 1.2 Objectives of the Southern Africa Consultation ............................................................................................................7 2. OVERVIEW OF DISASTERS AND HUMAN MOBILITY IN SOUTHERN AFRICA ..............................................................9 2.1 Natural Hazards and Climate Change in Southern Africa ............................................................................................10 2.2 Challenge -

PCBG) Quarter 2 2020: January 1, 2020 – March 31, 2020, Submitted to USAID/Mozambique

Parceria Cívica para Boa Governação Program (PCBG) Quarter 2 2020: January 1, 2020 – March 31, 2020, Submitted to USAID/Mozambique PCBG Agreement No. AID-656-A-16-00003 FY20 Quarterly Report Reporting Period: January 1 to March 31, 2020 Parceria Cívica para Boa Governação Program (PCBG) Crown Prince of Norway Haakon Magnus (left) shaking hands with TV Surdo’s Executive Director Felismina Banze (right), upon his arrival at TV Surdo. Submission Date: April 30, 2020 Agreement Number: Cooperative Agreement AID-656-A-16-00003 Submitted to: Jason Smith, USAID AOR Mozambique Submitted by: Charlotte Cerf Chief of Party Counterpart International, Mozambique Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development, Mozambique (USAID/Mozambique). It was prepared by Counterpart International. Parceria Cívica para Boa Governação Program (PCBG) Quarter 2 2020: January 1, 2020 – March 31, 2020, Submitted to USAID/Mozambique Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 4 PROGRAM DESCRIPTION............................................................................................................................... 6 Project Overview ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Eu Leio Agreement No. AID-656-A-14-00011

ATTACHMENT 3 Final Report Name of the Project: Eu Leio Agreement No. AID-656 -A-14-00011 FY2016: 5th Year of the Project EU LEIO Final Report th Date of Submission: October 20 , 2017 1 | P a g e Project Duration: 5 years (October 1st, 2014 to December 31th, 2019) Starting Date: October 1st 2014 Life of project funding: $4,372,476.73 Geographic Focus: Nampula (Mogovolas, Meconta, Rapale) and Zambézia (Alto Molocué, Maganja da Costa, Mopeia and Morrumbala) Program/Project Objectives (over the life of the project) Please include overview of the goals and objectives of the project (½-1 page). Goal of the project: Contribute to strengthen community engagement in education in 4 districts of Zambézia and 3 of Nampula province to hold school personnel accountable for delivering quality education services, especially as it relates to improving early grade reading outcomes. Objectives of the project: ❖ Improve quantity and quality of reading instruction, by improving local capacity for writing stories and access to educational and reading materials in 7 districts of Nampula and Zambezia provinces and; ❖ Increase community participation in school governance in 7 districts of Nampula and Zambezia provinces to hold education personnel accountable to delivering services, reduce teacher tardiness and absenteeism and the loss of instructional time in target schools. Summary of the reporting period (max 1 page). Please describe main activities and achievements of the reporting period grouped by objective/IR, as structured to in the monitoring plan or work plan. Explain any successes, failures, challenges, major changes in the operating environment, project staff management, etc. The project Eu leio was implemented from October 2014 to December 2019. -

Mozambique Fieldwork Report

Strategic Research into National and Local Capacity Building for DRM Mozambique Fieldwork Report Roger Few, Zoë Scott, Kelly Wooster, Mireille Flores Avila, Marcela Tarazona, Antonio Queface and Alberto Mavume. June 2015 Mozambique Fieldwork Report Acknowledgements The OPM Research Team would like to express sincere thanks to Roberto White from GFDRR Mozambique, Joao Ribeiro from INGC and Wild do Rosário from UN-Habitat for sharing their time and resources. We would also like to thank Joczabet Guerrero and Konstanze Kamojer for their invaluable advice and guidance in relation to the GIZ PRO-GRC project. Finally, we would like to thank all those interviewees and workshop attendees who freely gave their time, expert opinion and enthusiasm, and to Antonio Beleza who assisted the team during the fieldwork. This assessment is being carried out by Oxford Policy Management and the University of East Anglia. The Project Manager is Zoë Scott and the Research Director is Roger Few. For further information contact [email protected] Oxford Policy Management Limited 6 St Aldates Courtyard Tel +44 (0) 1865 207 300 38 St Aldates Fax +44 (0) 1865 207 301 Oxford OX1 1BN Email [email protected] Registered in England: 3122495 United Kingdom Website www.opml.co.uk © Oxford Policy Management i Mozambique Fieldwork Report Table of Contents Acknowledgements i List of Boxes and Tables 3 List of Abbreviations 4 1 Introduction and methodology 7 1.1 Introduction to the research 7 1.2 Methodology 8 1.2.1 Data collection tools 9 1.2.2 Case study procedure 10 1.2.3 -

Projectos De Energias Renováveis Recursos Hídrico E Solar

FUNDO DE ENERGIA Energia para todos para Energia CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFÓLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES Edition nd 2 2ª Edição July 2019 Julho de 2019 DO POVO DOS ESTADOS UNIDOS NM ISO 9001:2008 FUNDO DE ENERGIA CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFOLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES FICHA TÉCNICA COLOPHON Título Title Carteira de Projectos de Energias Renováveis - Recurso Renewable Energy Projects Portfolio - Hydro and Solar Hídrico e Solar Resources Redação Drafting Divisão de Estudos e Planificação Studies and Planning Division Coordenação Coordination Edson Uamusse Edson Uamusse Revisão Revision Filipe Mondlane Filipe Mondlane Impressão Printing Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Tiragem Print run 300 Exemplares 300 Copies Propriedade Property FUNAE – Fundo de Energia FUNAE – Energy Fund Publicação Publication 2ª Edição 2nd Edition Julho de 2019 July 2019 CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE RENEWABLE ENERGY ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS PROJECTS PORTFOLIO RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES PREFÁCIO PREFACE O acesso universal a energia em 2030 será uma realidade no País, Universal access to energy by 2030 will be reality in this country, mercê do “Programa Nacional de Energia para Todos” lançado por thanks to the “National Energy for All Program” launched by Sua Excia Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, Presidente da República de Moçam- His Excellency Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, President of the -

Daily Sun Article

South African Weather Service Watching the Weather to Protect Life and Property Strong winds and other kinds of rough weather can destroy WHOWHO WE WE ARE ARE houses and lives . THE South African Weather Service is the advanced equipment that aids us in the national provider of weather and climate-re- monitoring and prediction of weather pat- lated information. terns and the collection of climatic-related The past 10 years has seen an increase in information. weather-related natural disasters that have Our improved national weather observa- affected the lives of local communities. tion network has resulted in more accurate The deaths, injuries and damage to prop- weather and climate information, that helps erty caused have hampered sustainable de- us to provide bad weather early warning sys- velopment in both urban and rural commu- tems to the Republic of South Africa. nities, and we play an important role in The South African Weather Service is at helping the South African government to the forefront of providing weather and cli- lessen the effects of weather-related natural mate information in South Africa and we are disasters. confident that the years ahead will see even As an organisation, we are committed to more measures being developed to help pro- reducing the impact of these disasters by in- tect the South African public and keep vesting in the latest and most technologically weather related damage to a minimum. CELEBRATE WORLD METEOROLOGICAL DAY EACH year, on 23 March, the World Meteoro- a specialised agency of the United Nations. resulting distribution of water resources. community to see that that important weather logical Organisation (WMO) – a United Nations The theme for World Meteorological Day South Africa is represented at WMO by the and climate information is available and accessi- organisationwith189members–andtheworld- 2013 is “Watching the Weather to Protect Life CEO of the South African Weather Service ble for global programmes. -

The Infrastructure Industry in Mozambique Contents Siccode 502

THE INFRASTRUCTURE INDUSTRY IN MOZAMBIQUE Siccode 502 September 2015 Compiled by: CAROLE VEITCH [email protected] JOHANNESBURG OFFICE 7 STURDEE AVENUE, ROSEBANK, 2196 P O BOX 3044, RANDBURG, 2125 TEL: +27 11 280-0880 PORT ELIZABETH OFFICE 1ST FLOOR, BLOCK F, SOUTHERN LIFE GARDENS, 70 2ND AVE NEWTON PARK 6045 P O BOX 505, HUNTERS RETREAT, 6017 TEL: +27 41 394-0600 WEBSITE: WWW.WHOOWNSWHOM.CO.ZA REG NO: 1986/003014/07 DIRECTORS: MAUREEN MPHATSOE (CHAIRPERSON), MICHELLE BEETAR (EXPERIAN), PAXTON ANDERSON (EXPERIAN), ANDREW MCGREGOR (MANAGING) The Infrastructure Industry in Mozambique Contents Siccode 502 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................1 2. DESCRIPTION ..........................................................................................................................1 2.1. Supply Chain ............................................................................................................................. 2 2.2. Geographic Position ................................................................................................................. 3 2.2.1. Key Cities and Regions .................................................................................................... 4 3. SIZE OF THE INDUSTRY ............................................................................................................5 3.1. Key Indigenous and Foreign Players ........................................................................................ -

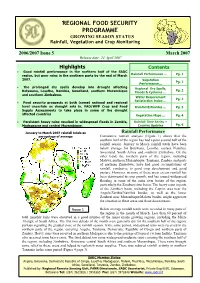

GROWING SEASON STATUS Rainfall, Vegetation and Crop Monitoring

REGIONAL FOOD SECURITY PROGRAMME GROWING SEASON STATUS Rainfall, Vegetation and Crop Monitoring 2006/2007 Issue 5 March 2007 Release date: 24 April 2007 Highlights Contents • Good rainfall performance in the northern half of the SADC region, but poor rains in the southern parts by the end of March Rainfall Performance … Pg. 1 2007. Vegetation Pg. 2 Performance… • The prolonged dry spells develop into drought affecting Regional Dry Spells, Pg. 2 Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland, southern Mozambique Floods & Cyclones … and southern Zimbabwe. Water Requirement Pg. 2 Satisfaction Index … • Food security prospects at both (some) national and regional level uncertain as drought sets in. FAO/WFP Crop and Food Rainfall Estimates … Pg. 3 Supply Assessments to take place in some of the drought affected countries Vegetation Maps … Pg. 4 • Persistent heavy rains resulted in widespread floods in Zambia, Rainfall Time Series + Madagascar and central Mozambique. Country Updates Pg. 6 January to March 2007 rainfall totals as Rainfall Performance percentage of average Cumulative rainfall analysis (Figure 1) shows that the southern half of the region has had a poor second half of the rainfall season. January to March rainfall totals have been below average for Botswana, Lesotho, eastern Namibia, Swaziland, South Africa and southern Zimbabwe. On the other hand, the northern parts of the region, including Malawi, northern Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and parts of northern Zimbabwe, have had good accumulations of rainfall, conducive to good crop development and good pasture. However, in some of these areas excess rainfall has been detrimental to crop growth, and has caused widespread flooding in some of the main river basins of the region, particularly the Zambezi river basin. -

Bds Needs Assessment in Nacala and Beira Corridor

USAID AgriFUTURO Mozambique Agribusiness and Trade Competitiveness Program Business Development Services Needs Assessment FINAL REPORT June 2010 By: Carlos Fumo (Senior Expert) TABLE OF CONTENTS 0. Note of Thanks .............................................................................................. 3 1. Acronyms and abbreviations.......................................................................... 4 2. General introduction ...................................................................................... 6 2.1. Background and introduction ................................................................. 6 3. Overall objectives of the Assessment ............................................................ 7 4. Deliverables ................................................................................................... 8 5. Methodology .................................................................................................. 8 5.1. Secondary Research .................................................................................. 9 5.2. Primary Research ................................................................................... 9 5.3. Data analysis and report writing ........................................................... 11 5.4. Sampling ............................................................................................... 11 6. The needs assessment process .................................................................. 13 7. The limitations of the study ......................................................................... -

Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Interventions in Rural Mozambique

Report | no. 360 Report | no. Impact evaluation of drinking water supply and sanitation interventions in rural Mozambique Since 2006, the UNICEF–Netherlands Partnership evaluation office. It found evidence of a large Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation has increase in the use of improved water sources been supporting Water Supply and Sanitation and in the ownership and use of latrines. Much of programmes in Mozambique. The largest the increase can be attributed to an innovative programme, the ‘One Million Initiative’ aims to approach to sanitation. However, water from bring improved sanitation and clean water to improved sources and even more importantly, over one million people in rural Mozambique. stored water, are not always safe to drink. An Half-way through the programme, a joint impact element of subsidy will continue to be needed to evaluation was carried out by IOB and UNICEF’s sustain facilities and services. More than Water Published by: Ministry of Foreign Affairs Impact evaluation of drinking water supply and sanitation interventions in rural Mozambique Policy and Operations Evaluation Department (IOB) P.O. box 20061 | 2500 eb The Hague | The Netherlands www.minbuza.nl/iob © Ministry of Foreign Affairs | October 2011| ISBN 978-90-5328-414-8 11Buz283729 | E This project was a product of a cooperation between: Impact evaluation of drinking water supply and sanitation interventions in rural Mozambique More than Water Mid-term impact evaluation: UNICEF – Government of The Netherlands Partnership for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene ‘One Million Initiative’, Mozambique Impact evaluation of drinking water supply and sanitation interventions in rural Mozambique Preface Drinking water supply and basic sanitation has been a priority for the Netherlands’ development co-operation and for UNICEF for many years. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories.