Speaking Notes of Bishop Brendan Leahy.PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bishop Brendan Leahy

th . World Day of Poor 19 November, 2017 No great economic success story possible as long as homelessness and other poverty crises deepen – Bishop Brendan Leahy Ireland cannot claim itself an economic success while it allows the neglect of its poor, Bishop of Limerick Brendan Leahy has stated in his letter to the people of the diocese to mark the first World Day of the Poor. The letter - read at Masses across the diocese for the official World Day of the Poor called by Pope Francis – says that with homelessness at an unprecedented state of crisis today in Ireland, it is almost unjust and unchristian to claim economic success. “Throughout the centuries we have great examples of outreach to the poor. The most outstanding example is that of Francis of Assisi, followed by many other holy men and women over the centuries. In Ireland we can think of great women such as Catherine McAuley and Nano Nagle. “Today the call to hear the cry of the poor reaches us. In our Diocese we are blessed to have the Limerick Social Services Council that responds in many ways. There are many other initiatives that reach out to the homeless, refugees, people in situations of marginalisation,” he wrote. “But none of us can leave it to be outsourced to others to do. Each of us has to do our part. Today many of us live a privileged life in the material sense compared to generations gone by, Today is Mission Sunday and the Holy Father invites all Catholics to contribute to a special needing pretty much nothing. -

“Among the Most Catechised but Among the Least Evangelised”? Religious Education in Ireland

“Among the Most Catechised but among the least Evangelised”? Religious Education in Ireland Br e n d a n Le a h y It has been said that the Irish are the most catechised but among the least evangelised in Europe. This article examines the contemporary situation of religious education in Ireland with a particular focus on its ecumenical aspects. It begins by outlining the historical journey in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that led Ireland to the current situation. On that basis it considers some of the issues that have arisen in recent times that have seen a dramatic change in religious practice in Ireland. It explores the issue of the relationship of parish, school and family. Keywords: National education; religious instruction; Vatican II; denominational school- ing; Archbishop Martin Since the coming of Patrick to Ireland in the fifth century, the issue of religious education has been important in Ireland. According to a legend, the Celtic princess Eithne asked Patrick: “Who is God, and where is God, of whom is God and where his dwelling?... This God of yours? Is he ever-living? Is he beautiful...? How will he be seen, how is he loved, how is he found?”1 To respond to questions such as this Patrick evangelised, catechised and inculturated the Gospel faith. And in a remarkably short span of time, there was a Celtic Christian body of poetry and literature. In particular it was the monastic communities that drove the Irish Christian experience of religious education and the transmission of the Christ-event in the first millennium.2 Traces of the Biblia pauperum, the religious education carried out in forms other than the written word, are very evident in Ireland. -

Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010

The Paschal Dimension of the 40 Days as an interpretive key to a reading of the new and serious challenges to faith in the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010 Kevin Doherty Doctor of Philosophy 2011 MATER DEI INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION A College of Dublin City University The Paschal Dimension of the 40 Days as an interpretive key to a reading of the new and serious challenges to faith in the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010 Kevin Doherty M.A. (Spirituality) Moderator: Dr Brendan Leahy, DD Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2011 DECLARATION I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D. is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. ID No: 53155831 Date: ' M l 2 - 0 1 DEDICATION To my parents Betty and Donal Doherty. The very first tellers of the Easter Story to me, and always the most faithful tellers of that Story. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A special thanks to all in the Diocese of Rockville Centre in New York who gave generously of their time and experience to facilitate this research: to Msgr Bob Brennan (Vicar General), Sr Mary Alice Piil (Director of Faith Formation), Marguerite Goglia (Associate Director, Children and Youth Formation), Lee Hlavecek, Carol Tannehill, Fr Jim Mannion, Msgr Bill Hanson. Also, to Fr Neil Carlin of the Columba Community in Donegal and Derry, a prophet of the contemporary Irish Church. -

Collegii Sti Patricii Saint Patrick's College

KALENDARIUM Collegii Sti Patricii APUD MAYNOOTH IN EXEUNTEM ANNUM MMXIX ET PROXIMUM MMXX KALENDARIUM Saint Patrick's College MAYNOOTH FOR THE YEAR 2019 - 2020 Saint Patrick’s College Maynooth County Kildare IRELAND Telephone: Ireland: 01-708-3600 International: +353-1-708-3600 Fax: Ireland: 01-708- 3441 International: +353-1-708-3441 Web Page: www.maynoothcollege.ie Editor: Caroline Tennyson Telephone: 01-708-3964 FAX: 01-708-3954 E-mail: [email protected] Whi le every care has been taken in compiling this publication, Saint Patrick’s College, Maynooth is not bound by any error or omission from the Kalendarium. 2 Contents CHAPTER I: INFORMATION AND PERSONNEL ......................... 7 President’s Welcome .......................................................................... 8 The Governing Body .......................................................................... 10 Official s of Saint Patrick’s College .................................................... 11 Academic Personnel ........................................................................... 12 Additional Personnel .......................................................................... 15 Useful Contacts for Students .............................................................. 16 Seminary Council ............................................................................... 18 Finance Council.................................................................................. 18 Audit & Risk Committee ................................................................... -

CNI Master October 29

October 29, 2018 ! Launch of Fallen in St Patrick’s Cathedral to mark end of World War 1 On Thursday evening at 7.30pm the official launch of Fallen will take place in St Patrick’s cathedral, Dublin, to mark the [email protected] Page !1 October 29, 2018 end of World War I. The evening will reflect on World War 1 and its historical and cultural impact and feature a short talk by historian and author Turtle Bunbury, poetry readings, and music performed by David Leigh and a Cathedral Chorister. Mr Bryan Dobson will compère the evening. This event is free of charge but advance registration is required. Video of installation in progress at - https://www.facebook.com/stpatrickscathedral/videos/vb. 37427412139/175743723357780/?type=2&theater Irish Churches make plans for Brexit Members of the Irish Inter-Church Meeting (IICM) are making preparations for how to best support their local communities during Brexit. The IICM, a high-level partnership between the Catholic Church and the Irish Council of Churches, explained in a letter earlier this month that an initial planning meeting had taken place in June 2018. Following this a draft framework was prepared that outlined areas of concern, relevant resources and experience within the churches, as well as possible actions that might be taken. Signed by its co-chairs, Bishop Brendan Leahy and Rev. Brian Anderson, the letter invited “groups within our member churches, local inter-church groups and partner organisations to contribute to the further development on this framework by responding to the enclosed consultation document”. [email protected] Page !2 October 29, 2018 Archbishop Martin of Armagh and Bishop McKeon of Derry were welcomed by Ambassador Saly Axworthy (centre) at the UK embassy to the Holy See during their recent attendance at the Synod. -

'One Diocese,Many Stories' Limerick Diocesan Assembly

‘ONE DIOCESE, MANY STORIES’ LIMERICK DIOCESAN ASSEMBLY 5th October 2019 Rathkeale House Hotel Table of Contents Foreword ....................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................... 5 Community and Sense of Belonging Theme ................................................... 6 Lectio Divina; Small Christian Communities: Newcastlewest Parish .................................... 7 Welcome and Hospitality: Cratloe Parish .............................................................................. 8 Local Pilgrimage: The Well at Barrigone: St Senan’s Parish (Shanagolden / Foynes / Robertstown) ........................................................................................................................ 10 Trócaire - making the story local: Limerick Diocese Trócaire Volunteer Group .................. 13 Laudato Si; Caring for our Common Home: Salesian Sisters ............................................... 15 Traveller Outreach ............................................................................................................... 16 Missionary Outreach; Synod Group of Frontline Workers .................................................. 17 Pastoral Care of the Family Theme ............................................................... 18 Family Fun Days: World Meeting of Families Diocesan Committee .................................... 19 Visible Reminders of an Invisible -

News Snippets Read All These Stories on Day for Life Is Celebrated on Sunday 2 October

Produced by the Catholic Communications Office of the Irish Bishops’ Conference. News Snippets Read all these stories on www.catholicnews.ie Day for Life is celebrated on Sunday 2 October. Speaking about this year’s theme ‘Everything is Con- nected’, Bishop Kevin Doran of Elphin said, “Laudato Si’ is not just about conserving the environment for its own “Education policy must have a priority option for the poor” – sake. It is about how we Archbishop Diarmuid Martin use and share the limited natural resources, which Speaking at the Annual Schools Mass in God originally intended for Clonliffe College, Dublin, on 27 September, all, including the Archbishop Diarmuid Martin of Dublin, generations yet to be born. For many in our world said that Catholic educational institutions, today, the management of especially the most prestigious, must find the environment is a matter ways to assist the disadvantaged. He said, of life and death. Download the Day for Life resources “Most of the religious orders which have on www.catholicbishops.ie: education as their mission sprung up from courageous and far-seeing founders and foundresses who were inspired to address the needs of the poor. Exclusivism should never be the dominant tone of any Catholic school.” Archbishop Martin said, “Failure to invest in fostering the educational opportunity of the disadvantaged from an early age is economical nonsense, which will end up in requiring greater investment when indeed it may be too late and less effective. Quality education is a fundamental right of all and a requirement of our respect for the dignity of the weakest in society.” Archbishop Martin said he was addressing his remarks in a special Bishop Brendan Leahy, way to the Catholic education community. -

Sharing the Good News

Gettingwww.veritas.ie Married? Book your SHARING THE GOOD NEWS marriage preparation course on Monthly newsletter for Dioceses and Parishes Issue 4 February 2014 www.accord.ie Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference Columba Centre, Saint Patrick’s College, Maynooth, Co Kildare Journeying Together - Challenges Facing the Migrant Today NEWS SNIPPETS „Journeying Together - Challenges Facing the Migrant Today‟, Sunday 2 February was the is the theme of a conference which will be jointly hosted by World Day of Consecrated the Bishops‟ Councils for Immigrants and Emigrants on Life. Speaking at the Vatican Pope Francis said: “Let us Wednesday 19 February in Dublin city centre. imagine a moment what The conference will celebrate the 10th anniversary of Erga would happen if there were no Migrantes Caritas Christi. It will also provide a unique opportunity to explore both nuns in hospitals, no nuns in emigration and immigration in an Irish, European and global context. The conference missions, no nuns in schools. Imagine a church without workshops will offer forums to discuss the effects of migration on the nuns! It is unimaginable.” undocumented, families, prisoners and trafficking. Lent begins on Speakers at the conference will include Archbishop Diarmuid Martin, 5 March - Ash Archbishop of Dublin, who will deliver the keynote address; Mr Wednesday. Stefan Kessler, Policy and Advocacy Officer for the Jesuit Refugee The message Service, Europe; and, Ms Cecilia Taylor-Camara, Senior Policy of Pope Adviser, Office for Migration Policy of the Catholic Church in England Francis for and Wales. The conference will be held at Jury‟s Inn Hotel, Custom House Quay, Lent 2014 is on the theme: “He became Dublin. -

Living Our Faith in a Time of Covid-19 Ten Tips Introduction

LIVING OUR FAITH IN A TIME OF COVID-19 TEN TIPS INTRODUCTION We will never forget 2020! A Spring lockdown, churches closed, Easter by webcam; children whose collective memory will be defined by this virus; Confirmation and First Communion ceremonies postponed, Leaving Cert students facing bewildering changes; people losing their jobs or fearing loss of work and our older generation very restricted in their activities. Funerals that had to be celebrated without the customary supports and gatherings of people. Over the summer we followed government roadmaps and longed to return to normality, or at least to something that resembled a familiar way of life. Now we are realising what “living with COVID-19” really means: we are daily confronted with uncertainties, regular changes and new codes of behaviour. COVID-19 has dramatically altered everyone’s daily life and powerfully exposed the vulnerability that all humans share. But longing to return to what was is never a constructive mindset - it only fuels our impulse to continually postpone. For Christians, postponing our mission is never a legitimate option; faith cannot be quarantined. It has to be lived in the circumstances of the time, so in this time of COVID-19, I would like to offer ten simple tips as an encouragement to keep watering the seed of faith within us. With our movements curtailed, we have a chance to take a more contemplative approach to life. We can check on our spiritual health, we can cultivate the interior space from which we draw when we bring our faith to action and work for the Kingdom of God. -

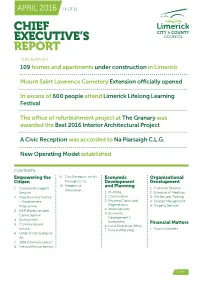

Chief Executive's Report

APRiL 2016 / 1 oF 11 ChiEF ExECutivE’s REPORt this month: 109 homes and apartments under construction in Limerick Mount Saint Lawrence Cemetery Extension officially opened In excess of 600 people attend Limerick Lifelong Learning Festival The office of refurbishment project at The Granary was awarded the Best 2016 Interior Architectural Project A Civic Reception was accorded to Na Piarsaigh C.L.G. New Operating Model established contents: Empowering the 9. civic Reception for na Economic Organisational Citizen Piarsaigh c.L.G. Development Development 10. Freedom of 1. community support and Planning 1. customer services information services 1. Planning 2. schedule of meetings 2. Department of Justice 2. conservation 3. Fire services training – Resettlement 3. housing capital and 4. change management Programme Regeneration 5. Property services 4. Water services 3. hAP shared services 5. economic centre Update Development / 4. environment investment Financial Matters 5. community and 6. Local enterprise office Leisure 7. Forward Planning 1. Financial matters 6. Limerick city Gallery of Art 7. 1916 commemoration 8. Fire and Rescue service 1 o1 oF 1F1 3 APRiL 2016 / 2 oF 11 ChiEF ExECutivE’s REPORt Empowering the Citizen 1. home and social Development Waiting List housing Waiting List 4345 Allocations Metropolitan Newcastle Adare – Cappamore – Total District West Rathkeale Kilmallock no of Units April 2016 14 1 0 4 19 Year to Date 44 7 16 14 81 2. Department of Justice – 3. hap shared services Centre update Resettlement Programme • the council operates the financial transactional shared the council has been asked by the Department of Justice service centre for all local authorities operating hAP and equality to chair an inter-agency working group to during the pilot phase. -

University and College Officers

University and College Officers Chancellor of the University Mary Terese Winifred Robinson, M.A., LL.B., LL.M. (HARV.), D.C.L. (by diploma OXON.), LL.D. (h.c. BASLE, BELF., BROWN, CANTAB., COL., COVENTRY, DUBL., FORDHAM, HARV., KYUNG HEE (SEOUL), LEUVEN, LIV., LOND., MELB., MONTPELLIER, N.U.I., N.U. MONGOLIA, POZNAN, ST AND., TOR., UPPSALA, WALES, YALE), D.P.S. (h.c. NORTHEASTERN), DOCTORAT EN SCIENCES HUMAINES (h.c. RENNES, ALBERT SCHWEITZER (GENEVA)), D.PHIL. (h.c. D.C.U., D.I.T.), D.UNIV. (h.c. COSTA RICA, EDIN., ESSEX), HON. FIEI, F.R.C.P.I. (HON.), HON. F.R.C.S.I., HON. F.R.C.PSYCH., HON. F.R.C.O.G., F.R.S.A., M.R.I.A., M.A.P.S. Pro-Chancellors of the University Sir Anthony O’Reilly, B.C.L. (N.U.I.), PH.D. (BRAD.), LL.D. (h.c. ALLEGHENY COLLEGE, CARNEGIE MELLON, DE PAUL, DUBL., LEIC., WHEELING COLLEGE), D.C.L. (h.c. INDIANA STATE), D.ECON.SC. (h.c. N.U.I.), D.SC. (ECON.) (h.c. BELF.), D.UNIV. (h.c. BRAD., OPEN), D.B.A. (h.c. BOSTON COLLEGE, WESTMINSTER COLLEGE), D.BUS.ST. (h.c. ROLLINS COLLEGE), HON. F.I.M.I. The Hon. Mrs Justice Susan Jane Gageby Denham, B.A., LL.B., LL.M. (COL.), LL.D. (h.c. BELF.) Eda Sagarra, M.A. (DUBL., N.U.I.), DR.PHIL. (VIENNA), LITT.D., M.R.I.A. Patrick James Anthony Molloy, B.B.S., P.M.D. (HARV.), LL.D. -

Current Newsletter (PDF)

PARISH PASTORAL UNIT ABBEYFEALE, ATHEA, TEMPLEGLANTINE, TOURNAFULLA, MOUNTCOLLINS 4th July 2021 www.abbeyfealeparish.ie email [email protected] Church Sacristy 068 - 51915 Parish Office 068 - 31133 Statement from Bishop Brendan Leahy on deferring The Morning Offering Co Parish Priests of the Pastoral Area First Holy Communion and Confirmation Fr Brendan Duggan 087/0562674 In a letter addressing parents and children, teachers and priests, Bishop Leahy said it is with Many of us would have grown up with the tradition of the great regret that, following both the email from the Taoiseach’s department on Wednesday and “Morning Offering.” It was an opportunity to offer everything Fr Denis Mullane 087/2621911 last week’s recommendation from the HSE, it is necessary to defer First Holy Communion and that would happen that day to the Lord, in a sense it meant the Confirmation ceremonies until further notice. whole day was a prayer. The following is a Fr Tony Mullins 087/2600414 “Due to the uncertainty at the moment regarding the impact of the Delta variant, we have been “Morning Offering” strongly advised that no ceremonies should be rescheduled until public health advice allows,” Fr Dan Lane (Retired) 087/2533030 Bishop Leahy wrote in the letter. that you might find helpful on your own prayer journey; “I deeply regret that we are in this position again of having to defer these special celebrations Priest on Call During the summer months Fr Dan Lane that you all had committed to and were so looking forward to. Your preparations still stand. “God of my life, I welcome this new day.