Rediscovering the Heart of Public Administration: the Normative Theory of in His Steps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pointe in Time Above and Beyond Sa

SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES POINTE IN TIME ABOVE AND BEYOND SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 2021 | 6PM | THE WESTIN PITTSBURGH Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre (PBT)’s highly anticipated, top-rated annual event – Pointe in Time – returns on Saturday, November 6, bringing elegance, artistry and fun back to The Westin Pittsburgh. The evening takes wing with the theme “Above and Beyond,” a nod to PBT’s resiliency and the forward vision of Artistic Director Susan Jaffe, who makes her debut as PBT’s fifth artistic leader. Honorary Chairs Nick and Sandi Nicholas invite you to be transfixed and transformed by the beauty and power of Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre while raising funds for one of the region’s most treasured cultural organizations. “We have been inspired by PBT’s triumph through the pandemic – its amazing Open Air Series at Flagstaff Hill, free virtual performances of Fireside Nutcracker, live performances at Carnegie Museum’s Hall of Sculpture and digital spotlights filmed at WQED. It is our honor to bring Pointe in Time to the next level in support of its innovation and future under new Artistic Director Susan Jaffe!” Nick and Sandi Nicholas 2021 Pointe in Time Honorary Chairs Swissvale native and Emmy Award-nominated actor and comedian Billy Gardell returns to his beloved Pittsburgh to attend Pointe in Time as celebrity guest and host of the live auction, which is sure to reach new heights. Billy Gardell currently stars in the CBS series Bob Hearts Abishola. Gardell starred with Melissa McCarthy in the hit series Mike & Molly as Officer Mike Biggs from 2010-2016. He had a recurring role on Young Sheldon and starred as Col. -

BEYOND THEOLOGY “What“What Wouldwould Jesusjesus Do?“Do?“

BEYOND THEOLOGY “What“What WouldWould JesusJesus Do?“Do?“ Host: Have you ever heard the question “What Would Jesus Do?” Do you know where it came from? How does it apply to the world in which we live today? Stay with us and you’ll find out. Host (Following title sequence): “What would Jesus Do?” is a question that pops up frequently in American culture. You might hear it in a movie or see it on a t-shirt. You sometimes see it in its abbreviated form – four simple letters … WWJD. It’s been popular among young Christians, who’ve displayed it as an expression of faith and relied upon it as a way to approach life. Although it may be not as popular as it was 20 or 25 years ago, it’s still around and it still gives people something to think about. Young people often begin to think more seriously about matters of ethics and morality as they gain more independence. At Harvard University, students have been outspoken in their demands for a meaningful education, prompting the university to develop a curriculum that includes moral reasoning. Rev. Peter Gomes (Memorial Church, Harvard University): In our desire to be even- handed and not evangelistic in any sense any more, we raise all the great issues of the day, but we don’t presume to preach to people -- the university doesn't presume to preach to people -- to say this is a view better than that or this is what you should do as opposed to that, do this and don’t do that. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

© Copyrighted by Charles Ernest Davis

SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Davis, Charles Ernest, 1933- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 00:54:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288393 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-5237 DAVIS, Charles Ernest, 1933- SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHTED BY CHARLES ERNEST DAVIS 1970 iii SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY by Charles Ernest Davis A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles Ernest Davis entitled Selected Works of Literature and Readability be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PqulA 1- So- 6G Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" *7-Mtf - 6 7-So IdL 7/3a This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination; The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1992 Boot Legger’s Daughter 2005 Dread in the Beast Best Contemporary Novel by Margaret Maron by Charlee Jacob (Formerly Best Novel) 1991 I.O.U. by Nancy Pickard 2005 Creepers by David Morrell 1990 Bum Steer by Nancy Pickard 2004 In the Night Room by Peter 2019 The Long Call by Ann 1989 Naked Once More Straub Cleeves by Elizabeth Peters 2003 Lost Boy Lost Girl by Peter 2018 Mardi Gras Murder by Ellen 1988 Something Wicked Straub Byron by Carolyn G. Hart 2002 The Night Class by Tom 2017 Glass Houses by Louise Piccirilli Penny Best Historical Mystery 2001 American Gods by Neil 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Gaiman Penny 2019 Charity’s Burden by Edith 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show 2015 Long Upon the Land Maxwell by Richard Laymon by Margaret Maron 2018 The Widows of Malabar Hill 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub 2014 Truth be Told by Hank by Sujata Massey 1998 Bag of Bones by Stephen Philippi Ryan 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys King 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank Bowen 1997 Children of the Dusk Philippi Ryan 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings by Janet Berliner 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by by Catriona McPherson 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen Louise Penny 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. King 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret King 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates Maron 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1994 Dead in the Water by Nancy 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Bowen Holder Penny 2013 A Question of Honor 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise by Charles Todd 1992 Blood of the Lamb by Penny 2012 Dandy Gilver and an Thomas F. -

Summer Reading List.Pages

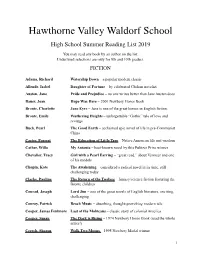

Hawthorne Valley Waldorf School High School Summer Reading List 2019 You may read any book by an author on the list. Underlined selections are only for 9th and 10th graders. FICTION Adams, Richard Watership Down – a popular modern classic Allende, Isabel Daughter of Fortune – by celebrated Chilean novelist Austen, Jane Pride and Prejudice – no one writes better than Jane Austen does Bauer, Joan Hope Was Here – 2001 Newbery Honor Book Bronte, Charlotte Jane Eyre – Jane is one of the great heroes in English fiction. Bronte, Emily Wuthering Heights – unforgettable “Gothic” tale of love and revenge Buck, Pearl The Good Earth – acclaimed epic novel of life in pre-Communist China Carter, Forrest The Education of Little Tree – Native American life and wisdom Cather, Willa My Antonia – best-known novel by this Pulitzer Prize winner Chevalier, Tracy Girl with a Pearl Earring – “great read,” about Vermeer and one of his models Chopin, Kate The Awakening – considered a radical novel in its time, still challenging today Clarke, Pauline The Return of the Twelves – fantasy/science fiction featuring the Bronte children Conrad, Joseph Lord Jim – one of the great novels of English literature, exciting, challenging Conroy, Patrick Beach Music – absorbing, thought-provoking modern tale Cooper, James Fenimore Last of the Mohicans – classic story of colonial America Cooper, Susan The Dark is Rising – 1974 Newbery Honor Book (read the whole series!) Creech, Sharon Walk Two Moons – 1995 Newbery Medal winner !1 Cushman, Karen Catherine, Called Birdy – 1995 Newbery -

Page 1 1 ALL in the FAMILY ARCHIE Bunker Emmy AWARD

ALL IN THE FAMILY ARCHIE Bunker Based on the British sitcom Till MEATHEAD Emmy AWARD winner for all DEATH Us Do Part MIKE Stivic four lead actors DINGBAT NORMAN Lear (creator) BIGOT EDITH Bunker Archie Bunker’s PLACE (spinoff) Danielle BRISEBOIS FIVE consecutive years as QUEENS CARROLL O’Connor number-one TV series Rob REINER Archie’s and Edith’s CHAIRS GLORIA (spinoff) SALLY Struthers displayed in Smithsonian GOOD Times (spinoff) Jean STAPLETON Institution 704 HAUSER (spinoff) STEPHANIE Mills CHECKING In (spinoff) The JEFFERSONS (spinoff) “STIFLE yourself.” “Those Were the DAYS” MALAPROPS Gloria STIVIC (theme) MAUDE (spinoff) WORKING class T S Q L D A H R S Y C V K J F C D T E L A W I C H S G B R I N H A A U O O A E Q N P I E V E T A S P B R C R I O W G N E H D E I E L K R K D S S O I W R R U S R I E R A P R T T E S Z P I A N S O T I C E E A R E J R R G M W U C O G F P B V C B D A E H T A E M N F H G G A M A L A P R O P S E E A N L L A R C H I E M U L N J N I O P N A M R O N Z F L D E I D R E D O O G S T I V I C A E N I K H T I D E T S A L L Y Y U A I O M Y G S T X X Z E D R S Q M 1 84052-2 TV Trivia Word Search Puzzles.indd 1 10/31/19 12:10 PM THE BIG BANG THEORY The show has a science Sheldon COOPER Mayim Bialik has a Ph.D. -

November 29 - December 5, 2020 Time Sta

November 29 - December 5, 2020 Time Sta. Sun, 11/29 Sta Mon, 11/30 Sta Tues, 12/1 Sta Wed, 12/2 Sta Thur, 12/3 Sta Fri, 12/4 Sta Sat, 12/5 Time 6am KYES CBS Sunday Morning KTUU Morning Edition KTUU Morning Edition KTUU Morning Edition KTUU Morning Edition KTUU Morning Edition KYES CBS Saturday 6am 6:30 Morning 6:30 7:00 The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show The Today Show Lucky Dog 7:00 7:30 Face the Nation Innovation Nation 7:30 8:00 NFL Today Animal Rescue 8:00 8:30 Inside College Bball 8:30 9:00 NFL KYES Let's Make KYES Let's Make KYES Let's Make KYES Let's Make KYES Let's Make NCAA Basketball 9:00 9:30 A Deal A Deal A Deal A Deal A Deal Baylor @ Gonzaga 9:30 10:00 Price is Right Price is Right Price is Right Price is Right Price is Right 10:00 10:30 10:30 11:00 The Young & The Young & The Young & The Young & The Young & College Football Today 11:00 11:30 The Restless The Restless The Restless The Restless The Restless College Football 11:30 12pm News at 12 News at 12 News at 12 News at 12 News at 12 12pm 12:30 NFL The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful The Bold & The Beautiful 12:30 1:00 The Talk The Talk The Talk The Talk The Talk 1:00 1:30 1:30 2:00 Dr. -

Criminal Minds

February 2020 #82 __________________________________________________________________________________________ _____ Broadcast Has Some Great TV Series Too By Steve Sternberg In December, I released my analysis of the 27 best TV series of 2019. In alphabetical order – Barry, Big Little Lies, Bosch, The Boys, Dead to Me, Fleabag, GLOW, Goliath, The Good Fight, The Good Place, Harlots, Jessica Jones, Killing Eve, The Kominsky Method, Mindhunter, The Morning Show, Mr Inbetween, Pose, Queen of the South, Rick & Morty, Russian Doll, Sneaky Pete, Star Trek: Discovery, Succession, This is Us, Vida, and Watchmen. As was the case with the Emmys, The Golden Globes, and virtually every TV critic, I demonstrated a clear bias against broadcast network series. Of my 27 best TV series, 15 are on streaming services, 5 are on premium cable, 5 are on ad-supported cable, and only 2 were on broadcast TV. There are, of course, some logical reasons for this. • Broadcast series have to answer to advertisers (and the FCC), so have limitations regarding language and sexual content that do not hinder cable or streaming services. A Sternberg Report Sponsored Message Reach thousands of highly engaged media and advertising decision makers. Contact [email protected] for details about advertising here. The Sternberg Report ©2020 __________________________________________________________________________________________ _____ • While cable and streaming series generally have between 6 and 13 episodes per season, broadcast series typically have between 17 and 24 episodes (although a few this season have 13). It’s difficult to write that many good episodes in a season, so it requires a lot more “filler.” • More broadcast dramas have self-contained episodes, as opposed to season-long story arcs, which are more prevalent on cable and streaming series. -

11Th Grade Recommended Readings

11th Grade Recommended Readings A Bell for Adano - John Hersey Sister Carrie - Theodore Dreiser A Lesson Before Dying - Ernest J. Gaines Slaughterhouse Five - Kurt Vonnegut A Raisin in the Sun - Lorraine Hansberry Sophie's Choice - William Styron A Yellow Raft in Blue Water - Michael Dorris Stranger in a Strange Land - Robert Heinlein An American Tragedy - Theodore Dreiser Streetcar Named Desire - Tennessee Williams And the Earth Did Not Devour Him - Tomas Rivera Studs Lonigan - James Farrell Babbitt - Sinclair Lewis The Andromeda Strain - Michael Crichton Black Boy - Richard Wright The Assistant - Bernard Malamud Catch 22 - Joseph Heller The Bell Jar - Sylvia Plath Daisy Miller - Henry James The Bridge of San Luis Rey - Thornton Wilder Death of a Salesman - Arthur Miller The Crucible - Arthur Miller East of Eden - John Steinbeck The Grapes of Wrath - John Steinbeck Ethan Frome - Edith Wharton The Great Gatsby - F. Scott Fitzgerald Fallen Angels - William Dean Myers The Great Santini - Pat Conroy Family - J. California Cooper The Invisible Man - Ralph Ellison First Confession - Montserrat Fontes The Jungle - Upton Sinclair For Whom the Bell Tolls - Ernest Hemingway The Kitchen God's Wife - Amy Tan Friendly Persuasion - Jessamyn West The Last Picture Show - Larry McMurtry Hotel New Hampshire - John Irving The Magician of Lublin - Isaac Singer Hunger of Memory - Richard Rodriguez The Maltese Falcon - Dashiell Hammett In Cold Blood - Truman Capote The Massacre at Fall Creek - Jessamyn West J.B. - Archibald McLeish The Mysterious Stranger -

Fall 2018 Network Primetime Preview

FALL 2018 PRIMETIME PREVIEW Brought to you by KATZ TV CONTENT STRATEGY CONTENT IS EVERYWHERE TELEVISION MAKES UP THE LION’S SHARE OF VIDEO MEDIA Television 80% Share of Time Spent with Video Media 4:46 Time Spent 5:57 H:MM/day All other with TV Video 20% All Other Video includes TV-Connected Devices (DVD, Game Console, Internet Connected Device); Video on Computer, Video Focused App/Web on Smartphone, Video Focused App/Web on Tablet Source: Nielsen Total Audience Report Q1 2018. Chart based on Total U.S. Population 18+ THE NEW FACES OF BROADCAST…FALL 2018 AND SOME RETURNING ONES TOO! SOME OF BROADCAST’S TOP CONTENT COMPETITORS NOTABLE NEW & RETURNING OTT SERIES NOTABLE NEW & RETURNING CABLE SERIES CONTENT – OTT & CABLE Every day more and more content Broadcast Network content creators defecting Quantity of content does not mean quality Critical, nomination-worthy successes Alternative Programming THE BIG PICTURE A Look at the Performance of All Viewing Sources in Primetime THE BIG PICTURE – PRIMETIME LANDSCAPE 2017/2018 Broadcast Other Pay Cable 7% Broadcast Networks 3% 20% Diginets 2% All Viewing PBS 3% Sources Total HH Share of Audience All Advertiser Supported DVR, VOD, Cable Ent. Vid. Games, 40% 13% News 20% 77% 10% Sports AOT 5% Note: BroadCast Networks=ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX, CW. BroadCast other = Azteca, Estrella, Ion, Telemundo, Univision, Unimas, Independent Broadcast. Diginets=Bounce TV, Cozi TV, EsCape, Grit, Heroes & Icons, LAFF, Me TV and PBS Source: Nielsen NNTV, 09/25/2017 - 05/23/2018, HH Shares, L+SD data. THE BIG PICTURE – PRIMETIME HH LANDSCAPE 2007/2008 2012/2013 2017/2018 58 56 53 -17% 49 48 48 in past 5 years 45 42 40 26 17 3 4 4 4 2012/2013 2017/2018 2007/2008 6 6 7 5 5 5 5 5 7 Broadcast DVR, Video AOT Pay Cable Ad-Supported Cable Ent. -

Church Bulletin Inserts-Year One

Church Bulletin Inserts-Year One 1 John Brown 32 Samuel Mills 2 John Adams 33 Jon Zundal 3 Walter Judd 34 Simeon Calhoun 4 Jennie Atwater 35 Mary Webb 5 Theodore Parker 36 Mary Ann Bickerdyke 6 Edward Beecher 37 Calvin Coolidge 7 Lloyd Douglas 38 Antoinette Brown 8 Sam Fuller 39 Francis Clark 9 Anne Bradstreet 40 Washington Gladden 10 Tabitha Brown 41 D.L. Moody 11 Zabdiel Boylston 42 David Hale 12 George Atkinson 43 David Livingston 13 Kathy Lee Bates 44 Edward Winslow 14 Lyman Beecher 45 Edward Taylor 15 George Burroughs 46 Harry Butman 16 Asa Turner 47 Martyn Dexter 17 Ray Palmer 48 Horace Bushnell 18 Charles Finney 49 Charles Ray 19 Susanna Winslow 50 Helen Billington 20 Elizabeth Tilley 51 Obidiah Holmes 21 Henry Beecher 52 Jermemiah Evarts 22 William Bradford 53 Leonard Bacon 23 Charles Sheldon 54 Reuben Gaylord 24 David Brainerd 55 Winifred Kiek 25 Constance Mary Coltman 56 John Eliot 26 Increase Mather 27 John Robinson 28 Lyman Abbott 29 Elizabeth Graham 30 Isabella Beecher Hooker 31 Charles Hammond Did you know John Brown… Descended from Puritans, John Brown opposed slavery and aspired to Congregational ministry. Illness derailed divinity studies; instead, he Call To Worship followed his father’s footsteps as a tanner. But he did become a noted abolitionist. His Pennsylvania tannery was a major stop on the L: Redeem the time, O God, before it’s gone and lost Underground Railroad, aiding an estimated 2,500 escaping slaves. C: When hearty pilgrim souls measured the cost Influenced by the 1837 murder of editor Elijah Lovejoy, the 1850 Fugitive L: And made the long voyage with hopes of something new Slave Law, and the 1856 sack of Lawrence, Kansas, Brown embraced C: We come to worship expecting something new! violence to oppose slavery.