Sex Abuse, the Catholic Church, & the Media George Weigel Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOLY FAMILY ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH Randallstown, Maryland

HOLY FAMILY ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH Randallstown, Maryland Welcome to our parish community! We praise God for the opportunity to worship God together. We will go forth to glorify God in our lives. New parishioners are requested to register as soon as possible. We invite you to become active members of our parish community. Please notify the Parish OfLice (ext. 4 or [email protected]) about any changes in your contact information (e.g., name, address). Registration forms can be obtained in the back of the church near the poor boxes, on the narthex tables, or via the Parish OfLice (ext. 4). Mission Statement The mission of Holy Family Parish is to help people to believe in Christ, belong to His Church, and bless our communities. We strive to fulLill our mission through worship, evangelization, faith formation, stewardship, fellowship, and service. 9531 Liberty Road | Randallstown, Maryland 21133 (Main Church & Parish OfLice) 10636 Liberty Road | Randallstown, Maryland 21133 (Old Church & Cemetery) SERVING THE PARISH PARISH OFFICE CONTACT INFO HOLY MASS SUNDAY & WEEKDAY Reverend Raymond Harris Phone 410.922.3800 Saturday at 4:00 pm (for Sunday) Pastor (ext. 6) Fax 410.922.3804 Sunday at 7:30 am, 10:30 am, Noon Email [email protected] Monday Saturday at 8:30 am [email protected] HOLY DAYS OF OBLIGATION Monsignor William A. Collins PARISH OFFICE HOURS T T Associate Pastor Emeritus Monday Friday 9:00 am 5:00 pm 8:30 am and 7:30 pm Other times by appointment CONFESSIONS Mr. Darron C. Woodus PARISH WEBSITE Saturday from 3:00 pm 3:45 pm Director of Faith Formation (ext. -

Information Guide Vatican City

Information Guide Vatican City A guide to information sources on the Vatican City State and the Holy See. Contents Information sources in the ESO database .......................................................... 2 General information ........................................................................................ 2 Culture and language information..................................................................... 2 Defence and security information ..................................................................... 2 Economic information ..................................................................................... 3 Education information ..................................................................................... 3 Employment information ................................................................................. 3 European policies and relations with the European Union .................................... 3 Geographic information and maps .................................................................... 3 Health information ......................................................................................... 3 Human rights information ................................................................................ 4 Intellectual property information ...................................................................... 4 Justice and home affairs information................................................................. 4 Media information ......................................................................................... -

The Church Today, January 27, 2020

CHURCH TODAY Volume LI, No. 1 www.diocesealex.org Serving the Diocese of Alexandria, Louisiana Since 1970 January 27, 2020 Be courageous! Eighth grade students from Holy Savior Menard; Sacred Heart, Moreauville; St. Anthony, Bunkie; St. Frances Cabrini, Alexandria; St. Mary’s Assumption, Cottonport; and St. Mary’s, Natchitoches came together for a day of retreat at Maryhill Retreat Center on Jan. 8. Speakers included Paul George, Father Louis Sklar, and Kelly Lombardi who encouraged students to designate a specific place to pray, and to incorporate prayer into their daily routines. INSIDE Holy Savior Menard names new Pro-life month activities draw to a close Prepare for Ash Wednesday, Feb. 26 principal for the 2020-2021 school year As pro-life activities draw to a close, see The Lenten season is just around the corner. The Diocese of Alexandria and Holy pages 6 and 7 for ways to support expecting See page 15 or the diocesan website for a Savior Menard announced the appointment of mothers, plus a few not-so-typical Catholic baby schedule of Lenten missions around the diocese. Christopher D. Gatlin as Principal of the school, names to share with your friends. effective July 1, 2020. See page 5 for more information. Congratulations, Mr. Gatlin! PAGE 2 CHURCH TODAY JANUARY 27, 2020 INDEX Looking back National / World News ............3 Question Corner ......................4 January 2005: Embracing the Liturgy ..............4 Left: Students in the library of Our Lady of Prompt Succor School; (standing) Weslee Diocesan News ........................5 -

February 5, 2010 Vol

CelebratingInside religious life World Day for Consecrated Life Mass celebrated on Criterion Jan. 31, page 20. Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com February 5, 2010 Vol. L, No. 17 75¢ Foreign doctors help Haitian staff ‘Supercentenarian’ in what remains At 110 years old, of hospital Emili Weil says PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti (CNS)—In Wyand MaryPhoto by Ann what remains of St. Francis de Sales Catholic faith Hospital, the doctors work under a pall of death. Even as teams of foreign doctors met with has sustained Haitian staffers to develop treatment plans and organize medical supplies in late January, her through up to 100 bodies remained in the collapsed three-story pediatrics and obstetrics wing. life’s challenges The hospital staff knows there were at least 25 child patients in the wing and a By Mary Ann Wyand similar number of family members at their sides when the building tumbled during the MILAN—Three centuries, 10 popes and magnitude 7 earthquake on Jan. 12. Staff 20 presidents. members make up the rest of the list of At 110, St. Charles Borromeo victims. parishioner Emelie Weil of Milan has lived Located a few blocks from the destroyed during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. presidential palace, the hospital had few She was born on Nov. 20, 1899, in remaining functions operating in late January. northern Kentucky and has lived during The staff was depending on experts from 10 papacies and 20 presidencies. around the world to help them treat Throughout 11 decades, Emelie said on earthquake victims. -

Vatican: FIA Becomes ASIF, New Set- up for Financial Information Authority

12/9/2020 Vatican: FIA becomes ASIF, new set-up for Financial Information Authority - Vatican News Vatican: FIA becomes ASIF, new set- up for Financial Information Authority Pope Francis on Saturday approved the new Statute of the Financial Information Authority (FIA), changing its name to Supervisory and Financial Information Authority (ASIF). The Statute redefines the role of its administrators and distributes some internal competencies. By Vatican News Pope Francis on Saturday approved the new Statute of the Financial Information Authority (FIA), which will henceforth be called the Supervisory and Financial Information Authority [It: Autorità di Supervisione e Informazione Finanziaria (ASIF)]. He issued a “chirograph” to approve the new Statute that comes into effect immediately on Saturday, December 5. A chirograph is a form of a papal document with legal force circulated among the Roman Curia. “In the overall reform desired by Pope Francis for the Holy See and the Vatican City State, aimed at greater transparency and the strengthening of controls in the economic-financial field, the Holy Father has approved the new Statute of the Financial Information Authority, which, from today's date, will be called the "Supervisory and Financial Information Authority" (ASIF),” said the Holy See Press Office in a release on Saturday. The change of name had been hinted at earlier in July when FIA published its annual report. Following the Pope’s approval of the ASIF Statute, FIA President Carmelo Barbagallo, who now becomes ASIF’s president, explained some of its important features. As part of the Pope’s overall reform of the Holy See and the Vatican City State, he said, it is regarding “transparency and strengthening of controls in the economic-financial field”. -

The Catholic Church in the Czech Republic

The Catholic Church in the Czech Republic Dear Readers, The publication on the Ro- man Catholic Church which you are holding in your hands may strike you as history that belongs in a museum. How- ever, if you leaf through it and look around our beauti- ful country, you may discover that it belongs to the present as well. Many changes have taken place. The history of the Church in this country is also the history of this nation. And the history of the nation, of the country’s inhabitants, always has been and still is the history of the Church. The Church’s mission is to serve mankind, and we want to fulfil Jesus’s call: “I did not come to be served but to serve.” The beautiful and unique pastoral constitution of Vatican Coun- cil II, the document “Joy and Hope” begins with the words: “The joys and the hopes, the grief and the anxieties of the men of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted, these are the joys and hopes, the grief and anxieties of the followers of Christ.” This is the task that hundreds of thousands of men and women in this country strive to carry out. According to expert statistical estimates, approximately three million Roman Catholics live in our country along with almost twenty thousand of our Eastern broth- ers and sisters in the Greek Catholic Church, with whom we are in full communion. There are an additional million Christians who belong to a variety of other Churches. Ecumenical cooperation, which was strengthened by decades of persecution and bullying of the Church, is flourishing remarkably in this country. -

Vespers on the World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation

N. 160902a Friday 02.09.2016 Vespers on the World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation Yesterday afternoon, in St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Francis presided at the celebration of vespers on the occasion of the World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation. The homily was pronounced by the Preacher to the Papal Household, Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, O.F.M. Cap., who emphasised that the sovereignty of human beings over the cosmos is not a triumphalism of the species but rather the assumption of responsibility for the weak, the poor and the helpless. “The God of the Bible, but also of other religions, is a God Who hears the cry of the poor … who disdains nothing He created”. “The Incarnation of the Word brought another reason to take care of the weak and the poor, whatever race or religion he may belong to. Indeed, this does not say merely that “God was made man”, but also that man was made God: that is, what type of man He chose to be: not rich or powerful, but poor, weak and helpless. … The form of the incarnation is no less important than the fact”. “This was the step further that Francis of Assisi, with his experience of life, was able to give to theology. … The Saint was moved to tears by the Nativity by … the humility and the poverty of the Son of God Who, ‘though He was rich, yet for your sake He became poor’. In him, love for poverty and love for creation went hand in hand, and had a common root in his radical renouncement of the will to possess”, explained Fr. -

A Study of the Roman Curia Francois-Xavier De Vaujany Jean Monnet University

Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) International Conference on Information Systems ICIS 2006 Proceedings (ICIS) December 2006 Conceptualizing I.S. Archetypes Through History: A Study of the Roman Curia Francois-Xavier de Vaujany Jean Monnet University Follow this and additional works at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2006 Recommended Citation de Vaujany, Francois-Xavier, "Conceptualizing I.S. Archetypes Through History: A Study of the Roman Curia" (2006). ICIS 2006 Proceedings. 83. http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2006/83 This material is brought to you by the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS) at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in ICIS 2006 Proceedings by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONCEPTUALIZING IS ARCHETYPES THROUGH HISTORY: A STUDY OF THE ROMAN CURIA Social, Behavioral and Organizational Aspects of Information Systems François-Xavier de Vaujany ISEAG Jean Monnet University [email protected] Abstract Many typologies of I.S. archetypes exist in the current literature. But very few rely on long term past perspectives, which could result in a precious opportunity to suggest innovative configurations related to specific institutional environments. On the other hand, historiography is a subject of growing interest in IS. Nonetheless, if many studies have already been carried out on the history of the technology or computer industries, very few have dealt with organizational IS history. This is regrettable, as it would give researchers a unique opportunity to understand long term IS dynamics and to grasp historical IS archetypes. Here, the author outlines a history of the IS of one of the oldest organizations in the world: the Roman Curia (the headquarters of the Catholic Church located within the Vatican). -

Kofc News Mar13

Knights of Columbus March All Saints Council 11402 2013 Dunwoody, Georgia Volume 20 (Established July 4th, 1994) “Opere et Veritate ” 1 John 3,18 Issue 3 Brothers: biblical scholar who speaks six languages. However he has caused controversies in the We are now more than halfway through the past few years with some of his comments, Fish Frys – and what an amazing start! While including linked clerical sex abuse with homo- the numbers are down slightly from last year’s sexuality. record-setting Lenten season, the customer experience is better than ever. The lines are The leading candidate from North America is moving faster, the orders are more accurate, Cardinal Marc Ouellet, 68, of Canada. and the food is fabulous. Ouellet served as Archbishop of Quebec from 2002 to 2010 before taking over as head of the Thanks to all the volunteers that have made powerful Vatican office that oversees the this possible. Your hard work not only helps appointment of the world’s bishops. Critics unify our parish and community, but fills our point to the poor state of the Church in council’s coffers with the funds that our Quebec during his tenure, and wonder if he charities have come to rely on. would be able to reinvigorate the faith in the Later this month the College of Cardinals will West. form a conclave in Vatican City to pick the Insiders have long said the Vatican has an next leader of the church. Just who are the unwritten rule that no American will ever favorites to replace Pope Benedict XVI? head the Catholic Church. -

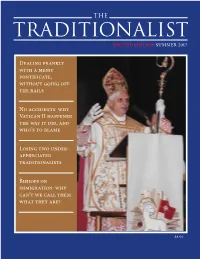

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

Of Jesus Christ

God’s reckoning upon a wayward world For years, Israel has had to live with existential threats from Iran and its neighbors, yet hardly anyone has done anything about it. The world seems to take for granted that Israel must live with such threats without ever doing anything about it either. Imagine what would happen if Russia, or China, made such threats to America, or vice versa. A few years ago, when the media went into another one of those cyclical frenzies with the notion that Israel was about to attack Iran and destroy that nation’s nuclear facilities before it developed nuclear weapons, we said that according to biblical prophecies it is Iran who will attack Israel, not the other way around. Our prediction has proven true. In February 2012, Iran attacked a number of Israeli missions abroad – in Georgia, India, and Thailand, to mention those that made it into the media. From there, attacking Israel itself is only a short step away. Iran has shown that its threats to Israel are not mere talk; that it is prepared to act on them. This has changed the name of the game. Israel is now entitled to reply and take action before a greater disaster hits the nation. This is not going to make Israel many friends. On the contrary, biblical prophecies tell us that this tiny nation will face the wrath of the entire world. We have said much about those prophecies in the past, and may yet say more in the future, God willing, but for now we will only post this prophecy as a reminder. -

Ave Papa Ave Papabile the Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations

FROM THE CENTRE FOR REFORMATION AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES Ave Papa Ave Papabile The Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations LILIAN H. ZIRPOLO In 1624 Pope Urban VIII appointed Marcello Sacchetti as depositary general and secret treasurer of the Apostolic Cham- ber, and Marcello’s brother, Giulio, bishop of Gravina. Urban later gave Marcello the lease on the alum mines of Tolfa and raised Giulio to the cardinalate. To assert their new power, the Sacchetti began commissioning works of art. Marcello discov- ered and promoted leading Baroque masters, such as Pietro da Cortona and Nicolas Poussin, while Giulio purchased works from previous generations. In the eighteenth century, Pope Benedict XIV bought the collection and housed it in Rome’s Capitoline Museum, where it is now a substantial portion of the museum’s collection. By focusing on the relationship between the artists in ser- vice and the Sacchetti, this study expands our knowledge of the artists and the complexity of the processes of agency in the fulfillment of commissions. In so doing, it underlines how the Sacchetti used art to proclaim a certain public image and to announce Cardinal Giulio’s candidacy to the papal throne. ______ copy(ies) Ave Papa Ave Papabile Payable by cheque (to Victoria University - CRRS) ISBN 978-0-7727-2028-2 or by Visa/Mastercard $24.50 Name as on card ___________________________________ (Outside Canada, please pay in US $.) Visa/Mastercard # _________________________________ Price includes applicable taxes. Expiry date _____________ Security code ______________ Send form with cheque/credit card Signature ________________________________________ information to: Publications, c/o CRRS Name ___________________________________________ 71 Queen’s Park Crescent East Address __________________________________________ Toronto, ON M5S 1K7 Canada __________________________________________ The Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Victoria College in the University of Toronto Tel: 416-585-4465 Fax: 416-585-4430 [email protected] www.crrs.ca .