Syrian Christian and Kerala History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 17 Christian Social Organisation

Social Organisation UNIT 17 CHRISTIAN SOCIAL ORGANISATION Structure 17.0 Objectives 17.1 Introduction 17.2 Origin of Christianity in India 17.2.1 Christian Community: The Spatial and Demographic Dimensions 17.2.2 Christianity in Kerala and Goa 17.2.3 Christianity in the East and North East 17.3 Tenets of Christian Faith 17.3.1 The Life of Jesus 17.3.2 Various Elements of Christian Faith 17.4 The Christians of St. Thomas: An Example of Christian Social Organisation 17.4.1 The Christian Family 17.4.2 The Patrilocal Residence 17.4.3 The Patrilineage 17.4.4 Inheritance 17.5 The Church 17.5.1 The Priest in Christianity 17.5.2 The Christian Church 17.5.3 Christmas 17.6 The Relation of Christianity to Hinduism in Kerala 17.6.1 Calendar and Time 17.6.2 Building of Houses 17.6.3 Elements of Castes in Christianity 17.7 Let Us Sum Up 17.8 Key Words 17.9 Further Reading 17.10 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 17.0 OBJECTIVES This unit describes the social organisation of Christians in India. A study of this unit will enable you to z explain the origin of Christianity in India z list and describe the common features of Christian faith z describe the Christian social organisation in terms of family, the role of the priest, church and Christmas among Syrian Christians of Kerala z identify and explain the areas of relationship between Christian and Hindu 42 social life in Kerala. Christian Social 17.1 INTRODUCTION Organisation In the previous unit we have looked at Muslim social organisation. -

Directory 2017

DISTRICT DIRECTORY / PATHANAMTHITTA / 2017 INDEX Kerala RajBhavan……..........…………………………….7 Chief Minister & Ministers………………..........………7-9 Speaker &Deputy Speaker…………………….................9 M.P…………………………………………..............……….10 MLA……………………………………….....................10-11 District Panchayat………….........................................…11 Collectorate………………..........................................11-12 Devaswom Board…………….............................................12 Sabarimala………...............................................…......12-16 Agriculture………….....…...........................……….......16-17 Animal Husbandry……….......………………....................18 Audit……………………………………….............…..…….19 Banks (Commercial)……………..................………...19-21 Block Panchayat……………………………..........……….21 BSNL…………………………………………….........……..21 Civil Supplies……………………………...............……….22 Co-Operation…………………………………..............…..22 Courts………………………………….....................……….22 Culture………………………………........................………24 Dairy Development…………………………..........………24 Defence……………………………………….............…....24 Development Corporations………………………...……24 Drugs Control……………………………………..........…24 Economics&Statistics……………………....................….24 Education……………………………................………25-26 Electrical Inspectorate…………………………...........….26 Employment Exchange…………………………...............26 Excise…………………………………………….............….26 Fire&Rescue Services…………………………........……27 Fisheries………………………………………................….27 Food Safety………………………………............…………27 -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Utsavam Bharananganam Sree Krishna Swami Temple

UTSAVAM BHARANANGANAM SREE KRISHNA SWAMI TEMPLE Panchayathh/ Municipality/ Bharananganam Panchayathh Corporation LOCATION District Kottayam Nearest Town/ Pala Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus station Mary Giri Bus Stop – 1.1 km Nearest Railway Kottayam Railway Station – 31.6 km station ACCESSIBILITY Nearest Airport Cochin International Airport – 79.8 km Sree Krishnaswami Temple Bharananganam – 686578 Phone: +91-4822-237078 CONTACT DATES FREQUENCY DURATION TIME January - February (Makaram) Annual 8 days ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) Bharananganam is also known as Dakshina Guruvayoor (Guruvayoor of South) because of the presence of Sree Krishna Swami Temple. The place name is closely associated with this temple. During their vanavasa (exile) Pandavas and Panchali stayed here for some days. On those days Yudhishtira performed Vishnu Pooja here. Yudhishtira decided to perform Dwadasi Pooja on Shukla Paksha Dwadasi day in the Malayalam month of Kumbham. But he had no idols of Lord Krishna to worship. Understanding the difficulty of His devotee, Lord Krishna gave a beautiful idol of Lord Vishnu to Vedavyasa Muni and Narada Muni and asked them to perform the pooja for Yudhishtira. Narada Muni and Vyasa Muni reached the place on the bank of holy Gauna (now Meenachil) river and installed the idol of Lord Vishnu in a suitable place and performed Vishnu pooja for Yudhishtira. The sages performed abhishekam with Gauna river water. Pandavas and Panchali conducted the Paranaveedal ritual to end their vratha. They stayed there for some more days and later left to another place. While leaving that place they appointed a local Brahmin to conduct daily poojas and gave him the wealth to construct a temple. -

Chapter I Christianity in Kerala: Tracing Antecedents

CHAPTER I CHRISTIANITY IN KERALA: TRACING ANTECEDENTS Introduction This chapter is an analysis of the early history of Christianity in Kerala. In the initial part it attempts to trace the historical background of Christianity from its origin to the end of seventeenth century. The period up to the colonial period forms the first part after which the history of the colonial part is given. This chapter also tries to examine how colonial forces interfered in the life of Syrian Christians and how it became the foremost factor for the beginning of conflicts. It tried to explain about the splits that happened in the community because of the interference of the Portuguese. It likewise deals with the relation of Dutch with the Syrian Christian community. It also discusses the conflict between the Jesuit and Carmelite missionaries. History of Christianity in Kerala in the Pre-Colonial Period Kerala, which is situated on the south west coast of Peninsular India, is one of the oldest centers of Christianity in the world. This coast was popularly known as Malabar. The presence of Christian community in the pre-colonial period of Kerala is an unchallenged reality. It began to appear here from the early days of Christendom.1 But the exact period in which Christianity was planted in Malabar, by whom, how or under what conditions, cannot be said with any confidence. However historians have offered unimportant guesses in the light of traditional legends and sources. The origin of Christianity was subject to wide enquiry and research by scholars. Different contradictory theories have been formulated by historians, religious leaders, and politicians on the Christian proselytizing in India. -

Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 1 Jan-2019 Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography Maya Subrahmanian Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subrahmanian, Maya (2019). Autonomous Women's Movement in Kerala: Historiography. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 1-10. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Autonomous Women’s Movement in Kerala: Historiography By Maya Subrahmanian1 Abstract This paper traces the historical evolution of the women’s movement in the southernmost Indian state of Kerala and explores the related social contexts. It also compares the women’s movement in Kerala with its North Indian and international counterparts. An attempt is made to understand how feminist activities on the local level differ from the larger scenario with regard to their nature, causes, and success. Mainstream history writing has long neglected women’s history, just as women have been denied authority in the process of knowledge production. The Kerala Model and the politically triggered society of the state, with its strong Marxist party, alienated women and overlooked women’s work, according to feminist critique. -

Travancore-Cochin Integration; a Model to Native States of India

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Travancore-Cochin Integration; A model to Native states of India Dr Suresh J Assistant Professor, Department Of History University College, Thiruvanathapuram Kerala University Abstract The state of Kerala once remained as an integral part of erstwhile Tamizakaom. Towards the beginning of the modern age this political terrain gradually enrolled as three native kingdoms with clear cut boundaries. The three native states comprised kingdom of Travancore of kingdom of Cochin, kingdom of Calicut These territories never enjoyed a single political structure due to the internal and foreign interventions. Travancore and Cochin were neighboring states enjoyed cordial relations. The integration of both states is a unique event in the history of India as well as History of Kerala. The title of Rajapramukh and the administrative division of Dewaswam is unique aspect in the course of History. Keywords Rajapramukh , Dewaswam , Panjangam, Yogam, annas, oorala, Melkoima Introduction The erstwhile native state of Travancore and Cochin forms political unity of Indian sub- continent through discussions debates and various agreements. The states situating nearby maintained interstate reactions in various realms. At occasionally they maintained cordial relation on the other half hostile in every respect. In different epochs the diplomatic relations of both the state were unique interns of political economic, social and cultural aspects. This uniqueness ultimately enabled both the state to integrate them ultimate into the concept of the formation of the state of Kerala. The division of power in devaswams and assumed the title Rajapramukh is unique chapters in Kerala as well as Indian history Volume XII, Issue VII, 2020 Page No: 128 Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Scope and relevance of Study Travancore and Cochin the native states of southern kerala. -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

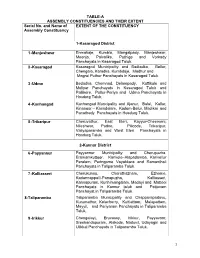

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Contributions of Regent Rani Gouri Lakshmi

International Journal of Research e-ISSN: 2348-6848 p-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 05 Issue 04 February 2018 Reforms In Modern Travancore : Contributions Of Regent Rani Gouri Lakshmi Bai Chinthu I B Research Scholar, Department of History, University of Kerala, Ph: 9446409444 Email: [email protected] Abstract Travancore a distinguished Native or Introduction Princely State in India was a Hindu feudal state (1729-1949) formerly, under control of Travancore was a former Hindu powerful Travancore Royal family. They were feudal Kingdom and Indian princely state one of the oldest ruling Dynasties in India, that had been ruled by the Travancore Royal including sovereign kings and even women Family from the capital at regents. They ruled from the capital city of Padmanabhapuram or Thiruvananthapuram. Padmanabhapuram and later from The Kingdom of Travancore at its zenith Thiruvananthapuram one of the oldest and comprised most of modern day southern earliest cities in India which was shifted Kerala, Kanyakumari district, and the during the time of Dharma raja. It had a long southernmost parts of Tamil Nadu tradition as a royal centre with its prosperity besides which it was also a great Centre of Gouri Lakshmi Bai was one education. The periods of Gouri Lakshmi of Travancore’s most popular Queens and Bai (1810-1814) deals with the four years of introduced several reforms in the state ruled Travancore history which constituted a from 1810 till 1813 and Regent from 1813 silent reformation in Travancore. Gouri till her death in 1815 for her son Swathi Lakshmi Bai was the first women ruler of Thirunal Rama Varma. -

Ernakulam District, Kerala State

TECHNICAL REPORTS: SERIES ‘D’ CONSERVE WATER – SAVE LIFE भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA जल संसाधन मंत्रालय MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES कᴂ द्रीय भूजल बो셍 ड CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD केरल क्षेत्र KERALA REGION भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका, एर्ााकु लम स्ज쥍ला, केरल रा煍य GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE तत셁वनंतपुरम Thiruvananthapuram December 2013 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, KERALA 饍वारा By टी. एस अनीता �याम वैज्ञातनक ग T.S.Anitha Shyam Scientist C KERALA REGION BHUJAL BHAVAN KEDARAM, KESAVADASPURAM NH-IV, FARIDABAD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 004 HARYANA- 121 001 TEL: 0471-2442175 TEL: 0129-12419075 FAX: 0471-2442191 FAX: 0129-2142524 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE TABLE OF CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2.0 RAINFALL AND CLIMATE ................................................................................... 4 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL ............................................................................ 5 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO .............................................................................. 6 5.0 GROUND WATER DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT .......................... 13 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ................................ 13 7.0 AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY ...................................................... -

The Menstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects 6-28-2017 The eM nstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity Jessie Norris Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Hindu Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Norris, Jessie, "The eM nstrual Taboo and Modern Indian Identity" (2017). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 694. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/694 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MENSTRUAL TABOO AND MODERN INDIAN IDENTITY A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of History and Degree Bachelor of Anthropology With Honors College Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Jessie Norris May 2017 **** CE/T Committee: Dr. Tamara Van Dyken Dr. Richard Weigel Sharon Leone 1 Copyright by Jessie Norris May 2017 2 I dedicate this thesis to my parents, Scott and Tami Norris, who have been unwavering in their support and faith in me throughout my education. Without them, this thesis would not have been possible. 3 Acknowledgements Dr. Tamara Van Dyken, Associate Professor of History at WKU, aided and counseled me during the completion of this project by acting as my Honors Capstone Advisor and a member of my CE/T committee.