Kazakhstan and Kyrgyz Republic National Immunization Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JNR0120SE Globalprofile.Pdf

JOURNAL OF NURSING REGULATION VOLUME 10 · SPECIAL ISSUE · JANUARY 2020 THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF STATE BOARDS OF NURSING JOURNAL Volume 10 Volume OF • Special Issue Issue Special NURSING • January 2020 January REGULATION Advancing Nursing Excellence for Public Protection A Global Profile of Nursing Regulation, Education, and Practice National Council of State Boards of Nursing Pages 1–116 Pages JOURNAL OFNURSING REGULATION Official publication of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing Editor-in-Chief Editorial Advisory Board Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, FAAN Mohammed Arsiwala, MD MT Meadows, DNP, RN, MS, MBA Chief Officer, Nursing Regulation President Director of Professional Practice, AONE National Council of State Boards of Nursing Michigan Urgent Care Executive Director, AONE Foundation Chicago, Illinois Livonia, Michigan Chicago, Illinois Chief Executive Officer Kathy Bettinardi-Angres, Paula R. Meyer, MSN, RN David C. Benton, RGN, PhD, FFNF, FRCN, APN-BC, MS, RN, CADC Executive Director FAAN Professional Assessment Coordinator, Washington State Department of Research Editors Positive Sobriety Institute Health Nursing Care Quality Allison Squires, PhD, RN, FAAN Adjunct Faculty, Rush University Assurance Commission Brendan Martin, PhD Department of Nursing Olympia, Washington Chicago, Illinois NCSBN Board of Directors Barbara Morvant, MN, RN President Shirley A. Brekken, MS, RN, FAAN Regulatory Policy Consultant Julia George, MSN, RN, FRE Executive Director Baton Rouge, Louisiana President-elect Minnesota Board of Nursing Jim Cleghorn, MA Minneapolis, Minnesota Ann L. O’Sullivan, PhD, CRNP, FAAN Treasurer Professor of Primary Care Nursing Adrian Guerrero, CPM Nancy J. Brent, MS, JD, RN Dr. Hildegarde Reynolds Endowed Term Area I Director Attorney At Law Professor of Primary Care Nursing Cynthia LaBonde, MN, RN Wilmette, Illinois University of Pennsylvania Area II Director Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Lori Scheidt, MBA-HCM Sean Clarke, RN, PhD, FAAN Area III Director Executive Vice Dean and Professor Pamela J. -

Kazakhstan Health Care Systems in Transition I

European Observatory on Health Care Systems Kazakhstan Health Care Systems in Transition I IONAL B AT AN RN K E F T O N R I WORLD BANK PLVS VLTR R E T C N O E N M S P T R O U L C E T EV ION AND D The European Observatory on Health Care Systems is a partnership between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, the Government of Norway, the Government of Spain, the European Investment Bank, the World Bank, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Health Care Systems in Transition Kazakhstan 1999 Kazakhstan II European Observatory on Health Care Systems AMS 5001888 CARE 04 01 03 Target 19 1999 Target 19 – RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE FOR HEALTH By the year 2005, all Member States should have health research, information and communication systems that better support the acquisition, effective utilization, and dissemination of knowledge to support health for all. By the year 2005, all Member States should have health research, information and communication systems that better support the acquisition, effective utilization, and dissemination of knowledge to support health for all. Keywords DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE EVALUATION STUDIES FINANCING, HEALTH HEALTH CARE REFORM HEALTH SYSTEM PLANS – organization and administration KAZAKHSTAN ©European Observatory on Health Care Systems 1999 This document may be freely reviewed or abstracted, but not for commercial purposes. For rights of reproduction, in part or in whole, application should be made to the Secretariat of the European Observatory on Health Care Systems, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. -

Social Protection System Review of Kyrgyzstan

OECD Development Pathways Social Protection System Review of Kyrgyzstan OECD Development Pathways OECD Development Pathways Social Protection System Review of Kyrgyzstan Social protection is at the heart of Kyrgyzstan’s development and is a priority of public policy. Pension coverage among today’s elderly is universal and a large number of contributory and non-contributory OECD Development Pathways programmes are in place to cover a wide range of risks. Kyrgyzstan has succeeded in maintaining the entitlements dating from the Soviet era while introducing programmes appropriate for its transition to a market economy. However, severe fi scal constraints have limited the coverage of these new arrangements and their capacity to adapt to challenges such as poverty, pervasive informality and emigration. Social Protection System The Social Protection System Review of Kyrgyzstan comes at a time when imbalances and fragmentation of social protection provision are undermining its impact and jeopardising its long-term sustainability. This Review of Kyrgyzstan Review proposes a systemic approach to addressing these challenges consistent with the Government of Kyrgyzstan’s own commitment to developing a coherent and extensive social protection system. It examines the current and future challenges facing Kyrgyzstan and analyses the capacity of existing social protection programmes to confront them. It also analyses the fi nancing of social protection and the sector’s current institutional framework. Finally, it proposes specifi c policies for establishing a social protection system and Social Protection System Review of Kyrgyzstan optimising the design of its component programmes. 00 Consult this publication on line at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264302273-en This work is published on the OECD iLibrary, which gathers all OECD books, periodicals and statistical databases. -

Mongolia Health System Review

Health Systems in Transition Vol. 9 No. 4 2007 Mongolia Health system review T. Bolormaa • Ts. Natsagdorj B. Tumurbat • Ts. Bujin B. Bulganchimeg • B. Soyoltuya B. Enkhjin • S. Evlegsuren E. Richardson Editor: Erica Richardson Health Systems in Transition Written by T. Bolormaa (Ministry of Health, Mongolia) Ts. Natsagdorj (Ministry of Health, Mongolia) B. Tumurbat (Ministry of Health, Mongolia) Ts. Bujin (Ministry of Health, Mongolia) B. Bulganchimeg (Ministry of Health, Mongolia) B. Soyoltuya (UNFPA, Mongolia) B. Enkhjin (UNFPA, Mongolia) S. Evlegsuren (Ministry of Health, Mongolia) E. Richardson (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies) Edited by E. Richardson (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies) Mongolia: Health System Review 2007 The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies is a partnership between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, the Governments of Belgium, Finland, Greece, Norway, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden, the Veneto Region of Italy, the European Investment Bank, the Open Society Institute, the World Bank, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Keywords: DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE EVALUATION STUDIES FINANCING, HEALTH HEALTH CARE REFORM HEALTH SYSTEM PLANS – organization and administration MONGOLIA © World Health Organization 2007, on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies All rights reserved. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies welcomes requests for permission -

Gender, Agriculture and Rural Development in Uzbekistan

GENDER, AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN UZBEKISTAN COUNTRY GENDER ASSESSMENT SERIES SSESSMENT A COUNTRY GENDER Gender, agriculture and rural development in Uzbekistan Country Gender Assessment Series Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Budapest, 2019 5HTXLUHGFLWDWLRQ )$2Gender, agriculture and rural development in Uzbekistan. &RXQWU\JHQGHUDVVHVVPHQWVHULHV%XGDSHVWSS /LFHQFH&&%<1&6$,*2 7KH GHVLJQDWLRQV HPSOR\HG DQG WKH SUHVHQWDWLRQ RI PDWHULDO LQ WKLV LQIRUPDWLRQ SURGXFW GR QRW LPSO\ WKH H[SUHVVLRQ RI DQ\ RSLQLRQ ZKDWVRHYHURQWKHSDUWRIWKH)RRGDQG$JULFXOWXUH2UJDQL]DWLRQRIWKH8QLWHG1DWLRQV )$2 FRQFHUQLQJWKHOHJDORUGHYHORSPHQWVWDWXVRI DQ\FRXQWU\WHUULWRU\FLW\RUDUHDRURILWVDXWKRULWLHVRUFRQFHUQLQJWKHGHOLPLWDWLRQRILWVIURQWLHUVRUERXQGDULHV7KHPHQWLRQRIVSHFLILF FRPSDQLHV RU SURGXFWV RI PDQXIDFWXUHUV ZKHWKHU RU QRW WKHVH KDYH EHHQ SDWHQWHG GRHV QRW LPSO\ WKDW WKHVH KDYH EHHQ HQGRUVHG RU UHFRPPHQGHGE\)$2LQSUHIHUHQFHWRRWKHUVRIDVLPLODUQDWXUHWKDWDUHQRWPHQWLRQHG 7KHYLHZVH[SUHVVHGLQWKLVLQIRUPDWLRQSURGXFWDUHWKRVHRIWKHDXWKRU V DQGGRQRWQHFHVVDULO\UHIOHFWWKHYLHZVRUSROLFLHVRI)$2 ,6%1 )$2 6RPHULJKWVUHVHUYHG7KLVZRUNLVPDGHDYDLODEOHXQGHUWKH&UHDWLYH&RPPRQV$WWULEXWLRQ1RQ&RPPHUFLDO6KDUH$OLNH,*2OLFHQFH &&%<1&6$,*2KWWSVFUHDWLYHFRPPRQVRUJOLFHQVHVE\QFVDLJROHJDOFRGHOHJDOFRGH 8QGHUWKHWHUPVRIWKLVOLFHQFHWKLVZRUNPD\EHFRSLHGUHGLVWULEXWHGDQGDGDSWHGIRUQRQFRPPHUFLDOSXUSRVHVSURYLGHGWKDWWKHZRUNLV DSSURSULDWHO\ FLWHG ,Q DQ\ XVH RI WKLV ZRUN WKHUH VKRXOG EH QR VXJJHVWLRQ WKDW )$2 HQGRUVHV DQ\ VSHFLILF RUJDQL]DWLRQ SURGXFWV RU VHUYLFHV7KHXVHRIWKH)$2ORJRLVQRWSHUPLWWHG,IWKHZRUNLVDGDSWHGWKHQLWPXVWEHOLFHQVHGXQGHUWKHVDPHRUHTXLYDOHQW&UHDWLYH -

Supporting Uzbekistan's Development Strategy in Key Policy Areas: Industrial Cluster, Cyber Security, S&T, and Insurance

2015/16 Knowledge Sharing Program with Uzbekistan Sharing Program 2015/16 Knowledge 2015/16 Knowledge Sharing Program with Uzbekistan: Supporting Uzbekistan’s Development Strategy in Key Policy Areas: Special Economic Zone, Industrial Development, Public Budgeting and Postgraduate Education 2015/16 Knowledge Sharing Program with Uzbekistan 2015/16 Knowledge Sharing Program with Uzbekistan Project Title Supporting Uzbekistan’s Development Strategy in Key Policy Areas: Special Economic Zone, Industrial Development, Public Budgeting and Postgraduate Education Prepared by Korea Development Institute (KDI) Supported by Ministry of Strategy and Finance (MOSF), Republic of Korea Prepared for The Government of Uzbekistan In Cooperation with Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations, Investment and Trade of the Republic of Uzbekistan (MFERIT) Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Uzbekistan (MOF) Institute of Forecasting and Macroeconomic Research (IFMR) Program Director Siwook Lee, Executive Director, Center for International Development (CID), KDI Program Officer Nu Ri Leem, Research Associate, Division of Policy Consultation & Evaluation, CID, KDI Senior Advisor Bong Kyun Kang, Former Minister of Ministry of Finance and Economy (MOFE) Authors Chapter 1. Siwook Lee, Executive Director, Center for International Development (CID), KDI Mutalib Hojimurotov, Head of the Coordination of Free Economic Zones Division, Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations, Investment and Trade of the Republic of Uzbekistan (MFERIT) Chapter 2. Changik Jo, Professor, Hallym University Hoon Heo, Research Associate, Center for International Development (CID), KDI Saidjon Kodirov, Chief Economist, Ministry of Finance for the Republic of Uzbekistan (MOF) Otabek Fazilkarimov, Chief Economist, Ministry of Finance for the Republic of Uzbekistan (MOF) Chapter 3. Jong ll Kim, Professor, Dongguk University Zulfiya Asfandiyarov, Senior Researcher, Institute of Forecasting and Macroeconomic Research (IFMR) Sanjar Karimov, Junior Researcher, Institute of Forecasting and Macroeconomic Research (IFMR) Chapter 4. -

Armenia Health System Review

Health Systems in Transition Vol. 15 No. 4 2013 Armenia Health system review Erica Richardson Erica Richardson (Editor) and Martin McKee (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Martin McKee, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom Elias Mossialos, London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom Sarah Thomson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Ewout van Ginneken, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Series coordinator Gabriele Pastorino, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Editorial team Jonathan Cylus, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Cristina Hernández-Quevedo, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Marina Karanikolos, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Maresso, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies David McDaid, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sherry Merkur, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Philipa Mladovsky, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Dimitra Panteli, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Wilm Quentin, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Bernd Rechel, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Erica Richardson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Sagan, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies International advisory board -

Sakhtar Akhtar

A PRELIMINARY BIBLIOGRAPHY ON LOWER AND MIDDLE-LEVEL HEALTH MANPOWER SAkhtar International Development Research Centre Information Sciences P. 0. Box 8500 Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1G 3H9 January, 1972 ARCH I V Akhtar no. 2 CONTENTS BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND OTHER ABSTRACTING SERV10S ON ALLIED HEALTH MANPOWER JOURNALS, BULLETINS, NEWSLETTERS, ETC., WHOLLY DEVOTED TO THE QUESTION OF ALLIED HEALTH MANPOWER BOOKS, PAMPHLETS, DOCUMENTS, MEMORANDUMS, ETC. ARTICLES APPEARING IN VARIOUS JOURNALS FOREIGN LANGUAGE PUBLICATIONS ADDENDUM 1. BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND OTHER ABSTRACTING SERVICES Excerpta Medica: Public Health, Social Medicine and Hyqiene, Section 17 under the heading 'Medical Education - Pararedi cal Education, No. 1.11.5. Health Manpower and the Medical Auxiliary: Bihlioqraohy,lntermediate Technology Group, London. Index Medicus under the Heading 'Physicians Assistant" as of January 1971. RecurrinqBibliography on Education in The Allied Health Professions, School of J\llied Medical Professions, The Ohio State Univer- sity, Columbus, Ohio. II. JOURNALS, BULLETINS, NEWSLETTERS, ETC., WHOLLY DEVOTED TO THE QUESTION OF ALLIED HEALTH MANPOWER. American Medical Association (AMA) News, Chicago. American Registary of Medical Assistants (ARMA) Bulletin, Thompsonville, Conn. American Socie1y of Medical Technologists (ASMT) Bulletin, monthly, Houston. Association of The School of Allied Health Professions, Newsletter, weekly, Washington, D.C. ColleQe Bulletin, The, American College of Medical Technoloqy. USSR* Feldsher i Akusherka (Feldsher and Midwife - a Russian language Journal). Journal of The International Confederation of Midwives, London. Professional Medical Assistants, The, bi-monthly, American Association of Medical Assistants, Chicago. * The country/organization in this column denotes that the work cited next to it is either on that particular country/organization or that it appeared in one of that country's/organization's publications. -

The Barefoot Doctors: China's Rural Health Care Revolution, 1968-1981

Wesleyan University The Honors College The Barefoot Doctors: China’s Rural Health Care Revolution, 1968-1981 by Cedric Howshan Bien Class of 2008 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in the East Asian Studies Program Middletown, Connecticut April, 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………5 Chapter 1: Characteristics of Rural Health Care in China, 1950-1981………...…..13 1.1 Patriotic Health Campaigns, 1950-1968 1.2 China’s Rural Health Care System, 1968-1981 1.3 Characteristics of the Barefoot Doctor Model, 1968-1981 1.4 Responsibilities and Interventions of the Barefoot Doctor Chapter 2: Barefoot Doctors, Human Development and Health Outcomes………...36 2.1 Processes, Functions, and Agency 2.2 Evaluating Basic Health Care Provision and Early-Age Mortality 2.3 Quality of Infant Mortality Data, 1955-1995 2.4 Chief Determinants of Infant Mortality Trends, 1955-1995 2.5 Health Personnel and Infant Mortality: A Thirteen-Province Study 2.6 Efficacy of Specific Interventions Chapter 3: Determinants of the Barefoot Doctors Program……...…………………65 3.1 Emulation of Foreign Models 3.2 Yan’an and the Formation of Maoist Ideology 3.3 Local Self-Sufficiency: The Cooperative Medical System and Chinese Medicine 3.4 Egalitarianism, Labor Surplus, and Incentives 3.5 Gender Equality, Female Empowerment, and Female Barefoot Doctors 3.6 Limits of Political and Ideological Determinants: The Great Leap Forward, 1958-1960 -

Human Rights in Patient Care a Practitioner Guide

Human Rights in Patient Care A PRACTITIONER GUIDE KYRGYZSTAN 1 | HUMAN RIGHTS IN PATIENT CARE: KYRGYZSTAN Human Rights in Patient Care A Practitioner Guide KYRGYZSTAN 2 | HUMAN RIGHTS IN PATIENT CARE: KYRGYZSTAN Copyright © 2012 by the Open Society Foundations Design: Jeanne Criscola | Criscola Design Cover photo: © Robert Lisak 3 | HUMAN RIGHTS IN PATIENT CARE: KYRGYZSTAN PREFACE 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 1 INTRODUCTION 7 2 INTERNATIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN PATIENT CARE 5 3 INTERNATIONAL PROCEDURES 75 4 COUNTRY-SPECIFIC NOTES 83 5 NATIONAL PATIENTS’ RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 89 6 NATIONAL PROVIDERS’ RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 157 7 NATIONAL PROCEDURES AND APPENDIXES 195 4 | HUMAN RIGHTS IN PATIENT CARE: KYRGYZSTAN 4 PREFACE The right to health has long been treated as a “second generation right,” which implies that it is not enforceable at the national level, resulting in a lack of attention and investment in its realization. However, this perception has significantly changed as countries increasingly incorporate the right to health and its key elements as fundamental and enforceable rights in their constitutions and embody those rights in their domestic laws. Significant decisions by domestic courts, particularly in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, have further contributed to the realization of the right to health domestically and to the establishment of jurisprudence in this area. Although these and other positive developments toward ensuring the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health represent considerable progress, the right to health for all without discrimination is not fully realized, because, for many of the most marginalized and vulnerable groups, the highest attainable standard of health remains far from reach. -

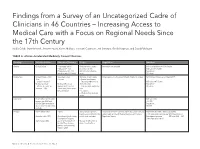

Findings from a Survey of an Uncategorized Cadre of Clinicians

Findings from a Survey of an Uncategorized Cadre of Clinicians in 46 Countries – Increasing Access to Medical Care with a Focus on Regional Needs Since the 17th Century Nadia Cobb, Marie Meckel, Jennifer Nyoni, Karen Mulitalo, Hoonani Cuadrado, Jeri Sumitani, Gerald Kayingo, and David Fahringer TABLE A. African Accelerated Medically Trained Clinicians Country Title Established Education/Training Scope Regulation Numbers Angola Clinical Officer – secondary school Medicine minor surgery Information not available Info not available on # CO in Angola – Education– 3 yrs. obstetrics (no CS) MD ratio .011/10,000 (Emigration of Drs 71% Work in rural and urban Population: based on early 2000 data) areas 19 million Burkina Faso Clinical Officer – 1942 Secondary school Medicine, minor surgery Organization – the Association Health Attaché in surgery 1241 Clinical Officers as of March 2015 Also : – 3 years – General practitioners – attaché’s desanté’ – Emergency obstetrics at MD ratio .0047/10,000 Medical assistant Medical officers can district hospital Population: – Attaché de santé’ en upgrade to CO’s with 6 – Can deal with obstructive 18 million chirurgie – 1965 month curriculum in emer- labor gency medicine – C sections – Work in urban and rural areas Cabo Verde Health Officer per literature MD ratio 2010 review– per WHO and .3/1,000 MOH in Cabo Verde these Population: do not exist – no other info 538,535 available Ethiopia Health Officer 1954 4 years 95% practice in primary Directorate of Health Facilities and Professionals Licensing Health Officers 2008 > 900 had graduated Health care unit (District HC) under Health and Health Related Services and Products 3,168 were under training– per WHO Health Sector discontinued in 1974 According to Health Sector both in rural and urban Regulation Agency Development program MD ratio 2009 .025 Development Program: /1000 Population: 96 mil started again 2004 accelerated program of Manage health center & Health Officer training district health offices (generic and upgrading) began in 2005. -

Uzbekistan Health Care Systems in Transition I

European Observatory on Health Care Systems Uzbekistan Health Care Systems in Transition i IONAL B AT AN RN K E F T O N R I WORLD BANK PLVS VLTR R E T C N O E N M S P T R O U L C E T EV ION AND D The European Observatory on Health Care Systems is a partnership between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, the Government of Greece, the Government of Norway, the Government of Spain, the European Investment Bank, the Open Society Institute, the World Bank, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Health Care Systems in Transition Uzbekistan 2001 Written by Farkhad A. Ilkhamov and Elke Jakubowski Edited by Steve Hajioff Uzbekistan ii European Observatory on Health Care Systems EUR/01/5012669 (UZB) 2001 RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE FOR HEALTH By the year 2005, all Member States should have health research, information and communication systems that better support the acquisition, effective utilization, and dissemination of knowledge to support health for all. Keywords DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE EVALUATION STUDIES FINANCING, HEALTH HEALTH CARE REFORM HEALTH SYSTEMS PLANS – organization and administration UZBEKISTAN ©European Observatory on Health Care Systems 2001 This document may be freely reviewed or abstracted, but not for commercial purposes. For rights of reproduction, in part or in whole, application should be made to the Secretariat of the European Observatory on Health Care Systems, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. The European Observatory on Health Care Systems welcomes such applications.