Workforce Development in Palau from Pre-Contact to 1999" (2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

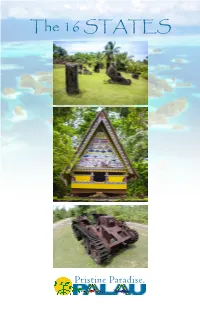

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Republic of Palau

REPUBLIC OF PALAU Palau Public Library Five-Year State Plan 2020-2022 For submission to the Institute of Museum and Library Services Submitted by: Palau Public Library Ministry of Education Republic of Palau 96940 April 22, 2019 Palau Five-Year Plan 1 2020-2022 MISSION The Palau Public Library is to serve as a gateway for lifelong learning and easy access to a wide range of information resources and to ensure the residents of Palau will be successful, literate and resourceful in the Palauan society and the world. PALAU PUBLIC LIBRARY BACKGROUND The Palau Public Library (PPL), was established in 1964, comes under the Ministry of Education. It is the only public library in the Republic of Palau, with collections totaling more than 20,000. The library has three full-time staff, the Librarian, the Library Assistant, and the Library Aide/Bookmobile Operator. The mission of the PPL is to serve as a gateway to lifelong learning and easy access to a wide range of information resources to ensure the residents of Palau will be successful, literate, and resourceful in the Palauan society and world. The PPL strives to provide access to materials, information resources, and services for community residents of all ages for professional and personal development, enjoyment, and educational needs. In addition, the library provides access to EBSCOHost databases and links to open access sources of scholarly information. It seeks to promote easy access to a wide range of resources and information and to create activities and programs for all residents of Palau. The PPL serves as the library for Palau High School, the only public high school in the Republic of Palau. -

The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau

THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF INITIAL HUMAN SETTLEMENT IN PALAU, WESTERN MICRONESIA by JESSICA H. STONE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jessica H. Stone Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Anthropology by: Scott M. Fitzpatrick Chairperson Nelson Ting Core Member Dennis H. O’Rourke Core Member Stephen R. Frost Core Member James Watkins Institutional Representative and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020 ii © 2020 Jessica H. Stone iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Jessica H. Stone Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology June 2020 Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia The initial settlement of Remote Oceania represents the world’s last major wave of human dispersal. While transdisciplinary models involving linguistic, archaeological, and biological data have been utilized in the Pacific to develop basic chronologies and trajectories of initial human settlement, a number of elusive gaps remain in our understanding of the region’s colonization history. This is especially true in Micronesia, where a paucity of human skeletal material dating to the earliest periods of settlement have hindered biological contributions to colonization models. The Chelechol ra Orrak site in Palau, western Micronesia, contains the largest and oldest human skeletal assemblage in the region, and is one of only two known sites that represent some of the earliest settlers in the Pacific. -

2017 Palau SOE FINAL

2017 State of the Environment Report Republic of Palau March 2017 An independent report presented to the President of the Republic of Palau by the National Environmental Protection Council (NEPC) Palau State of the Environment Report 2017 1 Dear President, On behalf of the National Environmental Protection Council (NEPC), I am pleased to present you with this State of the Environment Report 2017. This report is monumental in being the first self-reported assessment of our nation’s environmental conditions since independence. It thus presents perspectives on both our natural and man-made environment, and on our successes and challenges as a self-determined nation. This report is the first to synthesize scientific research into a single snapshot of our country and its direction. I am happy to report that where we have invested significantly, such as in our Human/ Urban Environment and in Protected Areas, we have good conditions and positive trends. Although our coral reefs have faced large disturbances, they seem to be recovering well. Unfortunately, many other natural resource indicators are in worse condition than they were in 1994, or trending the wrong way. This report verifies many of our perceived threats and indicates that particular effort is needed to conserve our fisheries and terrestrial resources. This reports builds on a 1994 State of the Environment report that established our baseline, and incorporates more than two decades of monitoring and research. Given the massive amount of information available, this report provides -

Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau

THREA TENED ENDEMIC PLANTS OF PALAU BIODI VERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 19: Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Craig Costion, James Cook University, Australia Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Photo credits: Craig Costion (unless cited otherwise) Cover photograph: Parkia flowers. © Craig Costion Series Editors: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, -

Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873 Margaret A

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 5-1993 Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873 Margaret A. Field University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Native American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Field, Margaret A., "Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873" (1993). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 141. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENOCIDE AND THE INDIANS OF CALIFORNIA , 1769-1873 A Thesis Presented by MARGARET A. FIELD Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies and Research of the Un1versity of Massachusetts at Boston in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS MAY 1993 HISTCRY PROGRAM GENOCIDE AND THE I NDIAN S OF CALIFORNIA, 1769-187 3 A Thesis P resented by MARGARET A. FIELD Approved as to style and content by : Clive Foss , Professor Co - Chairperson of Committee mes M. O'Too le , Assistant Professor -Chairpers on o f Committee Memb e r Ma rshall S. Shatz, Pr og~am Director Department of History ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank professors Foss , O'Toole, and Buckley f or their assistance in preparing this manuscri pt and for their encouragement throughout the project . -

Typhoon Surigae

PRCS Situation Report 15 Coverage of Situation Report: 6 PM, May 14 – 6 PM, May 19, 2021 TYPHOON SURIGAE Highlights • Initial Disaster Assessments for all households in Palau in the aftermath of Typhoon Surigae has ended. PRCS and State Governments are currently working together to distribute Non-food items (NFIs) and Cash Voucher Assistance (CVAs) to households affected by Typhoon Surigae. • International Organization for Migration Agency (IOM) Palau Office donated 1,500 tarpaulins and 350 hygiene kits to PRCS as part of relief supplies to be distributed to households affected by typhoon Surigae. • Non-food items (NFIs) for Category 1 damaged households in Melekeok, Ngaraard, Ngatpang, Ngchesar, and Ngeremlengui states have been picked up by their respective state governments. They will distribute to recipients in their states. Photos Above: (Left) NFIs for Category 1 damaged households packed and ready for Melekeok state R-DATs to pick up. (Middle) PRCS staff and volunteer assisting Ngeremlengui state R-DATs in NFIs unto their truck. (Right) PRCS staff going over distribution list with Airai state R-DAT. Photos by L. Afamasaga (left) & M. Rechucher (middle & right). • Babeldaob states with Category 2 damaged households have received Cash Voucher Assistance (CVAs) from PRCS through their own state governments. • A handover of CVAs between Koror and Airai states and PRCS took place at PRCS Conference room. The states also collected NFIs for Category 2 damaged households. The state governments are responsible for handing out CVAs and NFIs to households in their own states. Photo above: PRCS National Governing Board Chairman Santy Asanuma handing out CVAs to Koror State Government Chief of Staff Joleen Ngoriakl. -

Download from And

Designation date: 18/10/2002 Ramsar Site no. 1232 Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2014 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/doc/ris/key_ris_e.doc and http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/ris/key_ris_e.pdf Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 17, 4th edition). 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM Y Y Mr. Kashgar Rengulbai Tel: +680 544 5804/1 0 49 Program Manager Fax: +680 544 5090 Bureau of Agriculture Email: [email protected] Office of the Minister Designation d ate Site Reference Number PO Box 460 Koror, Palau PW 96940 Fax: +680 544 5090 Tel: +680 544 5804/1049 Email: [email protected] 2. -

Coral Reef Monitoring and 4Th MC Measures Group Workshop (2Nd Marine Measures Working Group Meeting)

Appendix H Finalizing the Regional MPA Monitoring Protocol: Coral Reef Monitoring and 4th MC Measures Group Workshop (2nd Marine Measures Working Group Meeting) WORKSHOP REPORT 6 – 9 February, 2012 Koror State Government Assembly Hall/ Palau International Coral Reef Center Conference Room Koror, Palau Appendix H TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... ii Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..... iv Acronyms ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. v List of Participants…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………....... vi Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... viii Background …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…… 1 Workshop objectives, outputs & deliverables……………………………………………………………………………... 2 Workshop Report ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………........... 3 DAY 1 Opening Remarks by Mrs. Sandra S. Pierantozzi, Chief Executive Officer, PICRC……….………………… 3 MC Workshop Background & Introduction (Dr. Yimnang Golbuu, PICRC).………………………..………….. 3 I. CAPACITY ENHANCEMENT PROJECT FOR CORAL REEF MONITORING Session 1: Capacity Enhancement Project for Coral Reef Monitoring (CEPCRM) 1. Update on CEPCRM since 2010 (Dr. Seiji Nakaya, JICA)…………………………………………. 4 II. REGIONAL MPA MONITORING PROTOCOL Session 2: Marine Monitoring Protocol 2. Introduction of the Marine Monitoring Protocol (Dr. Yimnang Golbuu, PICRC) ……. 5 Session 3: Jurisdictional Updates 3. Presentations from all MC states on ecological & socioeconomic monitoring since 2010.… -

Republic of Palau Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan, 2007-2012

National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007 - 2012 R National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 To all Palauans, who make the Cancer Journey May their suffering return as skills and knowledge So that the people of Palau and all people can be Cancer Free! Special Thanks to The planning groups and their chairs whose energy, Interest and dedication in working together to develop the road map for cancer care in Palau. We also would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Grant # U55-CCU922043) National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 October 15, 2006 Dear Colleagues, This is the National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau. The National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau provides a road map for nation wide cancer prevention and control strategies from 2007 through to 2012. This plan is possible through support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA), the Ministry of Health (Palau) and OMUB (Community Advisory Group, Palau). This plan is a product of collaborative work between the Ministry of Health and the Palauan community in their common effort to create a strategic plan that can guide future activities in preventing and controlling cancers in Palau. The plan was designed to address prevention, early detection, treatment, palliative care strategies and survivorship support activities. The collaboration between the health sector and community ensures a strong commitment to its implementation and evaluation. The Republic of Palau trusts that you will find this publication to be a relevant and useful reference for information or for people seeking assistance in our common effort to reduce the burden of cancer in Palau. -

Tour Guide Manual)

KOROR STATE GOVERNMENT Tour Guide Training and Certification Program Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................... 4 Palau Today .................................................................................................... 5 Message from the Koror State Governor ...........................................................6 UNESCO World Heritage Site .............................................................................7 Geography of Palau ...........................................................................................9 Modern Palau ..................................................................................................15 Tourism Network and Activities .......................................................................19 The Tour Guide ............................................................................................. 27 Tour Guide Roles & Responsibilities ................................................................28 Diving Briefings ...............................................................................................29 Responsible Diving Etiquette ...........................................................................30 Coral-Friendly Snorkeling Guidelines ...............................................................30 Best Practice Guidelines for Natural Sites ........................................................33 Communication and Public Speaking ..............................................................34 -

Analysis of Meaning,Content and Style:Poetry from the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau

Analysis of Meaning,Content and Style:poetry from the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau By Kimberly Kay Au Plan B paper 1 The field of Micronesian literature is still in a stage of infancy, compared to literature from the South Pacific. There is a substantial amount of post WW II literature from Micronesia, although there is not as much as in the South Pacific. Mark Skinner's Contemporary Micronesian Literature: A Preliminary Bibliography, a valuable compilation of about 800 works published in the post WW II era by 400 indigenous and non-indigenous writers is evidence of this (Skinner 1990:1). One reason why there is not as much work out of Micronesia compared to the South Pacific is because of the lack of promotion of creative writing in Micronesia. It is primarily because of the effort of certain individuals at various schools in the region that creative writing has developed as much as it has. Neither the Trust Territory nor the Government of Guam education departments actively encouraged creative writing. Another contributing factor is the lack of funding for publishing. (Skinner 1990:2-4). Although literary works from Micronesia are less polished and sophisticated than works from the South Pacific, they are nevertheless a creative form of expression and feeling worthy of study. Currently, very little research is being done in this particular field. Mark Skinner's bibliography is a compilation of Micronesian literature, but no one has delved into the actual works themselves. 2 This paper shall be breaking into "virgin territory", for in it I will be analyzing the content, form, structure and meaning of various poems from the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau.