2017 Palau SOE FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

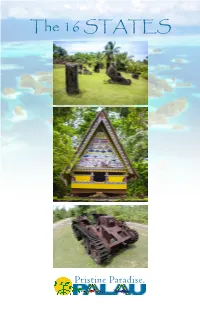

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau

THREA TENED ENDEMIC PLANTS OF PALAU BIODI VERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 19: Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Craig Costion, James Cook University, Australia Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Photo credits: Craig Costion (unless cited otherwise) Cover photograph: Parkia flowers. © Craig Costion Series Editors: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, -

Typhoon Surigae

PRCS Situation Report 15 Coverage of Situation Report: 6 PM, May 14 – 6 PM, May 19, 2021 TYPHOON SURIGAE Highlights • Initial Disaster Assessments for all households in Palau in the aftermath of Typhoon Surigae has ended. PRCS and State Governments are currently working together to distribute Non-food items (NFIs) and Cash Voucher Assistance (CVAs) to households affected by Typhoon Surigae. • International Organization for Migration Agency (IOM) Palau Office donated 1,500 tarpaulins and 350 hygiene kits to PRCS as part of relief supplies to be distributed to households affected by typhoon Surigae. • Non-food items (NFIs) for Category 1 damaged households in Melekeok, Ngaraard, Ngatpang, Ngchesar, and Ngeremlengui states have been picked up by their respective state governments. They will distribute to recipients in their states. Photos Above: (Left) NFIs for Category 1 damaged households packed and ready for Melekeok state R-DATs to pick up. (Middle) PRCS staff and volunteer assisting Ngeremlengui state R-DATs in NFIs unto their truck. (Right) PRCS staff going over distribution list with Airai state R-DAT. Photos by L. Afamasaga (left) & M. Rechucher (middle & right). • Babeldaob states with Category 2 damaged households have received Cash Voucher Assistance (CVAs) from PRCS through their own state governments. • A handover of CVAs between Koror and Airai states and PRCS took place at PRCS Conference room. The states also collected NFIs for Category 2 damaged households. The state governments are responsible for handing out CVAs and NFIs to households in their own states. Photo above: PRCS National Governing Board Chairman Santy Asanuma handing out CVAs to Koror State Government Chief of Staff Joleen Ngoriakl. -

Download from And

Designation date: 18/10/2002 Ramsar Site no. 1232 Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2014 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/doc/ris/key_ris_e.doc and http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/ris/key_ris_e.pdf Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 17, 4th edition). 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM Y Y Mr. Kashgar Rengulbai Tel: +680 544 5804/1 0 49 Program Manager Fax: +680 544 5090 Bureau of Agriculture Email: [email protected] Office of the Minister Designation d ate Site Reference Number PO Box 460 Koror, Palau PW 96940 Fax: +680 544 5090 Tel: +680 544 5804/1049 Email: [email protected] 2. -

Ngchesar State Protected Areas | PAN Site Mesekelat and Ngelukes Conservation Area Ngchesar State Vision Ngelukes Conservation A

Ngchesar State Protected Areas | PAN Site Mesekelat and Ngelukes Conservation Area January 2016 │ Fact Sheet Ngchesar State Ngchesar, also known as "Oldiais" is one of the sixteen states of Palau. It is the sixth largest state in terms of land, with an area of roughly 40 square kilometers, and is located on the eastern side of Babeldaob Island. It is also northwest of Airai State, and southeast of Melekeok State, where the Pa- lau Government Capitol is situated. The sacred totem of Ngchesar is the Stingray. Ngchesar is famous for its war canoe "kabekel" named “bisebush” which means “lightning”. Vision “We, the people of Ngchesar desire to protect and conserve Mesekelat, Ngelukes and Ngchesar in its entirety to ensure that these natural assets are sustained for the benefits of the people of Ngchesar today and into the future.” The Ngchesar State Protected Area System was created with the support from the Ngchesar State Conservation Management Action Plan Team who identified a system of state protected areas in and around Ngchesar and with full endorsement by the community and the leadership of the State. In 2002, Ngchesar State Public Law NSPL No. 146 established Ngchesar State Protected Area System consisting of the following two conservation are- as: Ngelukes Conservation Area Ngelukes Conservation Area is a 1km patch reef in front of Ngersuul village. Ngelukes’s substrate is mostly sand and rubble. Its interior is characterized by sea grass beds. Most of the corals in this patch reef are found along its outer edges along with macroalgae covered rubble. It is a shallow reef, howev- er at its edge there are depths that reach 20 feet at maximum high tide. -

Republic of Palau Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan, 2007-2012

National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007 - 2012 R National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 To all Palauans, who make the Cancer Journey May their suffering return as skills and knowledge So that the people of Palau and all people can be Cancer Free! Special Thanks to The planning groups and their chairs whose energy, Interest and dedication in working together to develop the road map for cancer care in Palau. We also would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Grant # U55-CCU922043) National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 October 15, 2006 Dear Colleagues, This is the National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau. The National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau provides a road map for nation wide cancer prevention and control strategies from 2007 through to 2012. This plan is possible through support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA), the Ministry of Health (Palau) and OMUB (Community Advisory Group, Palau). This plan is a product of collaborative work between the Ministry of Health and the Palauan community in their common effort to create a strategic plan that can guide future activities in preventing and controlling cancers in Palau. The plan was designed to address prevention, early detection, treatment, palliative care strategies and survivorship support activities. The collaboration between the health sector and community ensures a strong commitment to its implementation and evaluation. The Republic of Palau trusts that you will find this publication to be a relevant and useful reference for information or for people seeking assistance in our common effort to reduce the burden of cancer in Palau. -

Palauan Children Under Japanese Rule: Their Oral Histories Maki Mita

SER 87 Senri Ethnological Reports Senri Ethnological 87 Reports 87 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Palauan Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Their Oral Histories Thier Oral Histories Maki Mita Maki Mita National Museum of Ethnology 2009 Osaka ISSN 1340-6787 ISBN 978-4-901906-72-2 C3039 Senri Ethnological Reports Senri Ethnological Reports is an occasional series published by the National Museum of Ethnology. The volumes present in-depth anthropological, ethnological and related studies written by the Museum staff, research associates, and visiting scholars. General editor Ken’ichi Sudo Associate editors Katsumi Tamura Yuki Konagaya Tetsuo Nishio Nobuhiro Kishigami Akiko Mori Shigeki Kobayashi For information about previous issues see back page and the museum website: http://www.minpaku.ac.jp/publication/ser/ For enquiries about the series, please contact: Publications Unit, National Museum of Ethnology Senri Expo Park, Suita, Osaka, 565-8511 Japan Fax: +81-6-6878-8429. Email: [email protected] Free copies may be requested for educational and research purposes. Haines Transnational Migration: Some Comparative Considerations Senri Ethnological Reports 287 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule Their Oral Histories Maki Mita National Museum of Ethnology 2009 Osaka 1 Published by the National Museum of Ethnology Senri Expo Park, Suita, Osaka, 565-8511, Japan ©2009 National Museum of Ethnology, Japan All rights reserved. Printed in Japan by Nakanishi Printing Co., Ltd. Publication Data Senri Ethnological Reports 87 Palauan Children under Japanese Rule: Their Oral Histories Maki Mita. P. 274 Includes bibliographical references and Index. ISSN 1340-6787 ISBN 978-4-901906-72-2 C3039 1. Oral history 2. -

Palau Crop Production & Food Security Project

Palau Crop Production & Food Security Project Pacific Adaptation to Climate Change (PACC) REPORTING ON STATUS Workshop in Apia, Samoa May 10 –May 14, 2010 Overview of Palau Island: Palau is comprised of 16 states from Kayangel to the north, and Ngerchelong, Ngaraard, Ngiwal, Melekeok, Ngchesar, Airai, Aimeliik, Ngatpang, Ngeremlengui, and Ngardmau located on the big island of Babeldaob to Koror across the bridge to the south and Peleliu and Angaur farther south through the rock islands and Sonsorol and Hatohobei about a days boat ride far south. Ngatpang State was chosen as the PACC’s pilot project in Palau Pilot project in… due to its coastal area fringed with mangroves land uses Ngatpang State! including residential, subsistence agriculture and some small‐ scale commercial agriculture and mari‐culture. The state land area is approximately 9,700 Ngaremlengui State acres in size with the largest “Ngermeduu” bay in the Republic of Palau. Ngermeduu Bay NGATPANG STATE Aimeliik State Portions of the land surrounding the bay have been designated as Ngeremeduu conservation area and are co‐managed by the states of Aimeliik, Ngatpang and Ngaremlengui. There are a total of 389 acres of wetland habitat in Ngatpang, occurring Ngatpang State! for the most part along the low‐lying areas in addition to a total of 1,190 acres of mangrove forests ringing bay. The state has proposed a development of an aqua culture facility in the degraded area. Both wetlands and mangroves are considered an island‐wide resource, warranting coordinated management planning among the states. Ngatpang has a rich and diverse marine resources due to the bay and the associated outer and inner reefs. -

Bureau of Arts and Culture Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs 2013 Traditional Place Names of Palau: from the Shore to the Reef ______

TRADITIONAL PLACE NAMES OF PALAU: FROM THE SHORE TO THE REEF Bureau of Arts and Culture Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs 2013 Traditional Place Names of Palau: From the Shore to the Reef ____________________________ Ngklel a Beluu er a Belau er a Rechuodel: Ngar er a Kebokeb el mo er a Chelemoll by The Palau Society of Historians (Klobak er a Ibetel a Cherechar) and Bureau of Arts and Culture Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs Koror, Republic of Palau 96940 Traditional Customary Practices Palau Series 18-b 2013 THE SOCIETY OF HISTORIANS (KLOBAK ER A IBETEL A CHERECHAR) DUI\ NGAKL (Historian) BELUU (State) 1. Diraii Yosko Ngiratumerang Aimeliik 2. Uchelrutchei Wataru Elbelau Ngaremlengui 3. Ochob Rachel Becheserrak Koror 4. Floriano Felix Ngaraard 5. Iechadrairikl Renguul Kloulechad Ngarchelong 6. Ngirachebicheb August Ngirameketii Ngiwal 7. Rechiuang Demei Otobed Ngatpang 8. Ngirkebai Aichi Kumangai Ngardmau 9. Dirachesuroi Theodosia F. Blailes Angaur 10. Rebechall Takeo Ngirmekur Airai 11. Rechedebechei Ananias Bultedaob Ngchesar 12. Renguul Peter Elechuus Melekeok State 13. Smau Amalei Ngirngesang Peleliu 14. Obakrakelau Ngiraked Bandary Kayangel 15. Orue-Tamor Albis Sonsorol 16. Domiciano Andrew Hatohobei Bureau of Arts and Culture, Koror, Republic of Palau 96940 ©2013 by the Bureau of Arts and Culture All rights reserved. Published 2013. Palau Society of Historians Traditional Place Names of Palau: From the Shore to the Reef (Ngklel a Beluu er a Belau er a Rechuodel: Ngar er a Kebokeb el mo er a Chelemoll) Palauan Series 18-b ANTHROPOLOGY RESEARCH SERIES Volume 1 Rechuodel 1: Traditional Culture and Lifeways Long Ago in Palau by the Palau Society of Historians, English Translation by DeVerne Reed Smith. -

Glimpses Into Pacific Lives: Some Outstanding Women (Revised). INSTITUTION Northwest Regional Educational Lab., Portland, Oreg

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 280 923 UD 025 428 AUTHOR Simon-McWilliams, Ethel, Comp.; Green, Karen Reed, Ed. TITLE Glimpses into Pacific Lives: Some Outstanding Women (Revised). INSTITUTION Northwest Regional Educational Lab., Portland, Oreg. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE Feb 87 GRANT 008401776; 008401784 NOTE 175p.; For previous edition, see ED 270 542. PUB TYPE Reports General (140) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Achievement; *Community Leaders; Elementary Secondary Education; *Females; Foreign Countries; *Minority Groups; Role Models IDENTIFIERS American Samoa; Federated States of Micronesia; Guam; Hawaii; Marshall Islanth:; Northern Mariana Island5; *Pacific Islands; Palau (Belau) ABSTRACT This booklet provides brief biographies of women who have made outstanding contributions to the social and economic development of these Pacific islands: American Samoa, the Republic of Belau, the Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Hawaii, the Marshall islands, and the Northern Mariana Islands. The 66 women profiled include educators, health care providers, political leaders and government officials, lawyers, scientists, and social workers. (KH) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** GLIMPSES INTO PACIFIC LIVES: SOME OUTSTANDING WOMEN Compiled by Ethel Simon-McWilliams Program Director -

Island Towns

Island Towns Managing Urbanization in Micronesia John Connell and John PLea Occasional Paper 40 Center for Pacific Islands Studies School of Hawaiian, Asian & Pacific Studies University ofHawai'i at Manoa Honolulu and Research Institute for Asia & the Pacific University of Sydney to 1998 by John Connell and John PLea The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of AusAID or any other body associated with it. ISSN 0897-8905 Contents Preface v Acknowledgments vii PART ONE: THE CONTEXT OF URBANIZATION IN MICRONESIA 1 1 Introduction 3 Urban Beginnings 17 2 Population Migration and Urbanization 35 The Demographic Structure 37 Migration in the Region 48 International Migration 60 3 Urban Economy and Society 80 The Urban Economy 86 Employment and Urban Society 97 Conclusion 105 PART Two: URBAN DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 109 4 Urban Management and Planning 110 Land-Use Planning Goals 114 Land-Use Planning in the Federated States of Micronesia 119 Urban Management in Kiribati 122 Urban Planning in the Marshall Islands 126 Master Planning in Palau 127 Strengthening Planning Capabilities in Micronesia 130 5 Urban Land Policy 135 Federated States of Micronesia 137 Kiribati 146 Marshall Islands 149 Palau 151 Addressing the Priorities 154 6 Housing 158 The Urban Housing Process in Micronesia 160 Housing Conditions in Micronesia 163 ,ji Housing Policy in the Micronesian Countries 169 It Accommodating Micronesia 177 7 Public Utilities 181 Water Supply, Sewage Treatment, and Waste Disposal 183 Palau 185 Power and -

Cepf Small Grant Final Project Completion Report

CEPF SMALL GRANT FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT Organization Legal Name: Palau Conservation Society Threatened Species Awareness and Capacity Building in Project Title: Palau Date of Report: February 28th 2013 Report Author and Contact Joyce Beouch Information [email protected]; [email protected] CEPF Region: Polynesia- Micronesia, Site 144- Upland Forest, Babeldaob Island, Republic of Palau Strategic Direction: 2. Strengthen the conservation status and management of 60 key biodiversity areas. Grant Amount: 19,700 Project Dates: January 2012 to January 2013 Implementation Partners for this Project (please explain the level of involvement for each partner): The Palau Conservation Society (PCS) built the capacity of local communities to develop and implement conservation outreach projects. Ngchesar State Government- conservation officers from the state worked with PCS to develop an outreach project to raise the awareness of their community with respect to biodiversity in the state and in Palau in general with a specific focus on the Micronesian Imperial Pigeon and the Hawksbilll Turtle. Aimeliik State Government- conservation officers and board from the state worked with PCS to develop an outreach project to raise the awareness of their community with respect to biodiversity in the state and in Palau in general with a specific focus on the Micronesian Imperial Pigeon and the Hawksbilll Turtle. Ngardmau State Government - conservation officers from the state worked with PCS to develop an outreach project to strengthen leadership support for biodiversity conservation in the state and in Palau in general with a specific focus on the Micronesian Imperial Pigeon and the Hawksbilll Turtle. Belau National Museum (BNM) – Partner with PCS in developing outreach material for biodiversity conservation outreach.