Emily Dickinson, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermaphrodite Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams

Philosophies of Sex Etching of Julia Ward Howe. By permission of The Boston Athenaeum hilosophies of Sex PCritical Essays on The Hermaphrodite EDITED BY RENÉE BERGLAND and GARY WILLIAMS THE OHIO State UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Philosophies of sex : critical essays on The hermaphrodite / Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1189-2 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1189-5 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-9290-7 (cd-rom) 1. Howe, Julia Ward, 1819–1910. Hermaphrodite. I. Bergland, Renée L., 1963– II. Williams, Gary, 1947 May 6– PS2018.P47 2012 818'.409—dc23 2011053530 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Minion Pro and Scala Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction GARY Williams and RENÉE Bergland 1 Foreword Meeting the Hermaphrodite MARY H. Grant 15 Chapter One Indeterminate Sex and Text: The Manuscript Status of The Hermaphrodite KAREN SÁnchez-Eppler 23 Chapter Two From Self-Erasure to Self-Possession: The Development of Julia Ward Howe’s Feminist Consciousness Marianne Noble 47 Chapter Three “Rather Both Than Neither”: The Polarity of Gender in Howe’s Hermaphrodite Laura Saltz 72 Chapter Four “Never the Half of Another”: Figuring and Foreclosing Marriage in The Hermaphrodite BetsY Klimasmith 93 vi • Contents Chapter Five Howe’s Hermaphrodite and Alcott’s “Mephistopheles”: Unpublished Cross-Gender Thinking JOYCE W. -

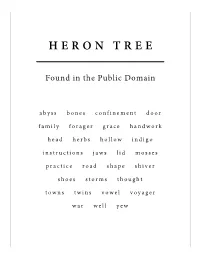

Found in the Public Domain

H E R O N T R E E Found in the Public Domain abyss bones confinement door family forager grace handwork head herbs hollow indigo instructions jaws lid mosses practice road shape shiver shoes storms thought towns twins vowel voyager war well yew HERON TREE EDITED BY Chris Campolo Rebecca Resinski This issue collects the poems published on the HERON TREE website from October 2016 through February 2017 as part of the Found in the Public Domain special series. herontree.com / [email protected] Issue originally published in February 2017; revised to include process notes in March 2018. All rights revert to individual authors upon publication. © 2018 by Heron Tree Press HERON TREE FOUND IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN HERON TREE PRESS CONWAY, ARKANSAS HERON TREE : FOUND IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN TABLE OF CONTENTS AND SOURCE TEXTS In the table of contents author names are linked to contributor information and titles are linked to poems. In the issue titles are linked to notes on source and process. 1 DEBORAH PURDY : Where It May Be “A Lament for S. B. Pat Paw,” Louisa May Alcott “Morning Song” and “A Song Before Grief,” Rose Hawthorne Lathrop [As imperceptibly as grief], Emily Dickinson “Ode to Silence” and “Journey,” Edna St. Vincent Millay [Not knowing when the dawn will come], Emily Dickinson 2 SARAH ANN WINN : Nature, Chrome Painted The Land of Little Rain, Mary Hunter Austin 3 HOWIE GOOD : How to Create an Unreliable Narrator titles of artworks by Lee Kit, Leslie Hewitt, and Brent Birnbaum 4 MELISSA FREDERICK : [32] AND [43] sonnets 32 and 43, William Shakespeare 6 CAREY VOSS : Henry Banner AND Emma Barr interviews of Henry Banner (with Samuel S. -

EMILY DICKINSON's POETIC IMAGERY in 21ST-CENTURY SONGS by LORI LAITMAN, JAKE HEGGIE, and DARON HAGEN by Shin-Yeong Noh Submit

EMILY DICKINSON’S POETIC IMAGERY IN 21ST-CENTURY SONGS BY LORI LAITMAN, JAKE HEGGIE, AND DARON HAGEN by Shin-Yeong Noh Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Andrew Mead, Research Director ______________________________________ Patricia Stiles, Chair ______________________________________ Gary Arvin ______________________________________ Mary Ann Hart March 7, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Shin-Yeong Noh iii To My Husband, Youngbo, and My Son iv Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without many people who aided and supported me. I am grateful to all of my committee members for their advice and guidance. I am especially indebted to my research director, Dr. Andrew Mead, who provided me with immeasurable wisdom and encouragement. His inspiration has given me huge confidence in my study. I owe my gratitude to my teacher, committee chair, Prof. Patricia Stiles, who has been very careful and supportive of my voice, career goals, health, and everything. Her instructions on the expressive performance have inspired me to consider the relationship between music and text, and my interest in song interpretation resulted in this study. I am thankful to the publishers for giving me permission to use the scores. Especially, I must thank Lori Laitman, who offered me her latest versions of the songs with a very neat and clear copy. She is always prompt and nice to me. -

Did a Woman Write “The Great American Novel”? Judging Women’S Fiction in the Nineteenth Century and Today

Did a Woman Write “The Great American Novel”? Judging Women’s Fiction in the Nineteenth Century and Today Melissa J. Homestead University of Nebraska A JURY OF HER PEERS: AMERICAN WOMEN WRITERS FROM ANNE BRADSTREET TO ANNIE PROULX, by Elaine Showalter. New York: Knopf, 2009. 608 pp. $30.00 cloth; $16.95 paper. In the fall of 2009, as I was preparing to teach a senior capstone course for English majors on the nineteenth-century American novel and ques- tions of literary value and the canon, I went trolling for suggestions of recent secondary readings about canonicity. The response came back loud and clear: “The canon wars are over. We all teach whatever we want to teach, and everything is fine.” My experiences with students suggest that, at least in American literary studies before 1900, the canon wars are not over, or, perhaps, they have entered a new stage. Most of my students had heard of James Fenimore Cooper, and a few had read him, but none (with the exception of one student who had previously taken an early American novel class with me) had even heard of his contemporary Catharine Maria Sedgwick. Most had heard of Harriet Beecher Stowe, and a few had previously read Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Although some aspiring fiction writers initially objected to what they felt was an overly intrusive narrator, I succeeded in persuading the class to read Stowe’s novel with respectful attention. All of them had heard of Mark Twain, and all but a tiny minority had read his Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885). -

Anne Bradstreet Exhibits the Puritan “Plain Style” in Her Poetry

• Anne Bradstreet exhibits the Puritan “plain style” in her poetry • Mary Rowlandson’s account of her 11week captivity encouraged antiIndian sentiment in the colonies • From her writings, Abigail Adams shows early feminist causes • Meriwether Lewis contributed vast knowledge of botany, geology, and geography in his journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition • In his poem “Thanatopsis”, William Cullen Bryant exhibits both transcendental and Calvinist elements • Show how Concord, Massachusetts was the first rural American artist’s colony offering a spiritual and cultural alternative to American materialism • Ralph Waldo Emerson reveals his transcendentalist beliefs in his essay “Self Reliance” • Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “From Nature” reflects the 19th Century romantic thought • Ralph Waldo Emerson took much of his spiritual insight from readings of Eastern religions as seen in his poem, “Brahma” • Transcendentalists like Bronson Alcott and Robert Owens and George and Sophia Ripley created experimental utopian colonies to counteract the attitudes created by the Industrial Revolution • Transcendentalism was a philosophical, literary, social, and theological Movement • Civil disobedience and peaceful resistance used today by activists had their base from Henry David Thoreau’s beliefs • Edgar Allan Poe was culturally informed, not isolated, as a writer during his time • Sojourner Truth encouraged abolitionism and women’s suffrage in her evangelistic preaching • Walt Whitman’s greatest legacy is the invention of American free verse • Walt Whitman -

Emily Dickinson - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Emily Dickinson - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Emily Dickinson(10 December 1830 – 15 May 1886) Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was an American poet. Born in Amherst, Massachusetts, to a successful family with strong community ties, she lived a mostly introverted and reclusive life. After she studied at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she spent a short time at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family's house in Amherst. Thought of as an eccentric by the locals, she became known for her penchant for white clothing and her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, even leave her room. Most of her friendships were therefore carried out by correspondence. Although Dickinson was a prolific private poet, fewer than a dozen of her nearly eighteen hundred poems were published during her lifetime. The work that was published during her lifetime was usually altered significantly by the publishers to fit the conventional poetic rules of the time. Dickinson's poems are unique for the era in which she wrote; they contain short lines, typically lack titles, and often use slant rhyme as well as unconventional capitalization and punctuation. Many of her poems deal with themes of death and immortality, two recurring topics in letters to her friends. Although most of her acquaintances were probably aware of Dickinson's writing, it was not until after her death in 1886—when Lavinia, Emily's younger sister, discovered her cache of poems—that the breadth of Dickinson's work became apparent. -

Maya Angelou

MAYA ANGELOU AND THE FREEDOM POETRY OF ADVENT MAYA ANGELOU AND THE FREEDOM POETRY OF ADVENT “I’m always amazed when people walk up to me and say, ‘I’m a Christian.’ I think, ‘Already? You already got it?’ I’m working at it, which means that I try to be kind and fair and generous and respectful and courteous to every human being.” + Maya Angelou Maya Angelou was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1928. In 1965, working as a journalist in Ghana, she met Malcolm X, and decided to return to the United States to help him establish his Organization of African-American Unity – but only a few days after she arrived, he was assassinated. A few years later, she agreed to work with Martin Luther King Jr. – but then he, too, was killed, on her 40th birthday. Angelou fell into a depression. Some friends recommended her to an editor at Random House, saying she should write an autobiography – but Angelou repeatedly refused. Then her friend, the writer James Baldwin, suggested a creative strategy to the editor: call her one more time, Baldwin said, and say you’re calling to tell her that you’ll stop bothering her, and that it’s probably just as well that she’s refused, because it’s terribly difficult to write an autobiography that’s also good literature. The plan worked like a charm: Angelou immediately agreed to take on the challenge. On writing the book, she later said, “Once I got into it I realized I was following a tradition established by Frederick Douglass – the slave narrative – speaking in the first-person singular talking about the first-person plural, always saying ‘I’ meaning ‘we.’” That first autobiography became I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, published in 1969. -

Love and Logic in the School (Workshops for Parents)

Thrive, a local community organization in collaboration with Bozeman Schools, offers classes that provide information and strategies for parents so they know what they can do to ensure their child’s school success. Topics cover age appropriate child development, building a strong learning environment, raising responsible kids, setting high expectations and clear boundaries. Becoming a Love and Logic Parent Presented by: Bozeman Public Schools and The Parent Liaison Program, a signature program of Thrive This six-week workshop, developed by the Love and Logic Institute, Inc. will help you develop specific answers and strategies for some of those difficult moments in parenting. Parent Liaisons at your school will be facilitating this class. $10 fee for the workbook. Limited childcare available. Hawthorne Sept. 25-Oct. 30 Tuesdays 5:30-7:30pm Libby Michaud, Parent Liaison Emily Dickinson Sept. 27-Nov. 8 Thursdays 6:00-8:00pm Steve Wellington,Parent Liaison CJMS Sept. 27-Nov.8 Thursdays 6:00-8:00pm Lori Van Vleet, Parent Liaison Hyalite Sept. 27-Nov. 8 Thursdays 6:00-8:00pm Cindy Ballew, Parent Liaison Irving Jan. 17-Feb 21 Thursdays 6:00-8:00pm Cindy Ballew, Parent Liaison Longfellow Jan. 15-Feb 19 Tuesdays 6:00-8:00pm Sacajawea Jan.15-Feb 19 Tuesdays 6:00-8:00pm Ashley Jones, Parent Liaison Morning Star Mar. 21-Apr 25 Thursdays 6:00-8:00pm Libby Michaud, Parent Liaison Whittier Mar. 21-Apr 25 Thursdays 6:00-8:00pm Lori Van Vleet, Parent Liaison Thriving Kinders A Workshop Designed for Parents of Kindergartners Thrive has designed Thriving Kinders, a class for parents of children who are entering Kindergarten. -

Emily Dickinson: Writing It 'Slant'

Published on Great Writers Inspire (http://writersinspire.org) Home > Emily Dickinson: Writing it 'Slant' Emily Dickinson: Writing it 'Slant' American poet Emily Dickinson [1] (1830-1886) is today best known for her use of slant-rhyme, conceits, and unconventional punctuation, as well as her near-legendary reclusive habits. She was part of a prominent Amherst, Massachusetts family. As neither Emily nor her sister Lavinia ever married, they remained at home and looked after their parents. Dickinson became very reclusive with age, sometimes speaking to guests from behind a door, but she also maintained close, intellectual friendships through her correspondence with literary men Samuel Bowles and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, as well as her best friend, neighbour, and sister-in-law Susan Gilbert Dickinson. Dickinson has perhaps unfairly earned a reputation for being a rather morbid poet, focused intently on death. Death was certainly a preoccupation of Dickinson's, especially as her New England culture was permeated with evangelical Christian questions of salvation, redemption, and the afterlife. However, Dickinson also wrote powerfully about nature and questions of knowledge, faith, and love. When Dickinson did write about death, she wrote it 'slant', coming to the subject with her own distinctive twist. In the 1863 poem 'I heard a Fly buzz ? when I died' (in Poems, Third Series [2]; Chapter 4:46) Dickinson enumerates the elements of a conventional and pious deathbed scene: 'I willed my Keepsakes ? Signed away | What portion of me be | Assignable?'. The speaker has completed her earthly business while the watchers wait for 'that last Onset ? when the King | Be witnessed ? in the Room ?'. -

Teacher Lesson Plan 2

Sponsored Educational Materials Teacher Lesson Plan 2 3 Read the poem out loud Objectives: once to model fluent reading, • summarize a poem then have students read the • determine the theme poem out loud to a partner. of a poem 4 Explain that understanding Materials: What Does what happens in the poem This Poem Mean? Student is the first step in analyzing Worksheet, teacher-selected poetry. As a class, paraphrase poem for class analysis the poem, either by Possible poems: assigning each stanza to a • “Life Doesn’t Frighten Me” small group of students or by Maya Angelou by completing a think-aloud • “Your World” by Georgia as a whole class. Douglas Johnson 5 If necessary, stop to define Time: one 40-minute class any terms in the poem that period are unfamiliar to students. Essential Question: Have students complete How does 6 Point out that 8 analyzing a poem help us to understanding the feeling the What Does This Poem understand it better? of the poem is an important Mean? Student Worksheet step in analyzing it. Reread to apply these skills to a the poem, focusing on the new poem. question “What type of feeling or mood does this Lesson Steps: poem have?” Use think-pair- Express Yourself share to collect students’ Poetry Contest Explain to students that ideas. Invite students to circle 1 Your students could win a poetry is a way that writers the words or punctuation $400 Scholastic Gift Card OR an express themselves. We marks that helped create the American Girl® 2017 Girl of the often understand poetry mood of the poem. -

Overview of Activity (PDF)

ANNALS OF AMERICAN HISTORY ACTIVITY STUDYING HISTORY THROUGH WRITING Britannica Student Activity Worksheets Using Annals of American History from Encyclopædia Britannica with your students incorporates reading, writing, and American history. Britannica’s activity worksheets for your students can be found online at http://corporate.britannica.com/training. To find the student activity, click the link for “Student Activity: Studying History Through Writing” under “Annals of American History”. These activities enable students to further develop analytical skills by critiquing a historical document. Students will analyze the document by answering questions about the author’s purpose, audience, writing style, emotional appeal, and impact on American history. The students will then write a review of this document, and finally, interpret the message with a current day perspective. Learning Objectives • Learn about American history through the original words of history-makers. • Identify various literary tools in writings and to analyze their usage in context. • Develop group skills in language arts, including critique and discussion. • Build and enhance nonfiction reading comprehension skills. Selected Documents Discovery of the New World -- 1493 The Bill of Rights -- 1789 Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death -- 1775 The Gettysburg Address -- 1863 The Declaration of Independence -- 1776 A Program for Social Security -- 1935 The Articles of Confederation -- 1781 The Moon Landing -- 1969 Constitution of the United States -- 1787 J. Carter’s Nobel Peace Prize Lecture --2002 Selected Authors Samuel Adams Hillary Clinton John F. Kennedy Jane Addams Christopher Columbus Abraham Lincoln Madeleine Albright Emily Dickinson Ronald Reagan Susan B. Anthony Benjamin Franklin Eleanor Roosevelt Neil Armstrong Patrick Henry Franklin D. -

Dissertations on Margaret Fuller

DISSERTATIONS ON MARGARET FULLER Margaret Fuller on national culture: Political idealism through self-culture by Beste, Lori Anne, PhD; UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT, 2006 Transcendental teaching: A reinvention of American education (Amos Bronson Alcott, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller) by Heafner, Christopher Allen, PhD; UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA, 2005 'Ravishing harmony': Defining Risorgimento in Margaret Fuller's dispatches from Italy to the 'New York Tribune', 1847 to 1850 by Jo, Hea-Gyong, PhD; WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY, 2005 Sympathy and self-reliance: Transcendentalism's emergence from the culture of sentiment (Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Orestes Brownson) by Robbins, Tara Leigh, PhD; THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL, 2005 International nationalism: World history as usable past in nineteenth-century United States culture (James Fenimore Cooper, Margaret Fuller, John Lothrop Motley, William Hickling Prescott, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) by Roylance, Patricia Jane, PhD; STANFORD UNIVERSITY, 2005 'When Plato- was a certainty-': Classical tradition and difference in works by Phillis Wheatley, Margaret Fuller, and Emily Dickinson by Dovell, Karen Lerner, PhD; STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT STONY BROOK, 2004 Extraordinary women all: The influence of Madame de Stael on Margaret Fuller and Lydia Maria Child (France) by Lord, Susan Toth, PhD; KENT STATE UNIVERSITY, 2004 'How came such a man as Herbert?': Allusions to George Herbert