The Sharp Edge of Stephen's City Nick Jeffrey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Vision for Social Housing

Building for our future A vision for social housing The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing Building for our future: a vision for social housing 2 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Contents Contents The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing For more information on the research that 2 Foreword informs this report, 4 Our commissioners see: Shelter.org.uk/ socialhousing 6 Executive summary Chapter 1 The housing crisis Chapter 2 How have we got here? Some names have been 16 The Grenfell Tower fire: p22 p46 changed to protect the the background to the commission identity of individuals Chapter 1 22 The housing crisis Chapter 2 46 How have we got here? Chapter 3 56 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 3 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 4 The consequences of the decline p56 p70 Chapter 4 70 The consequences of the decline Chapter 5 86 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 90 Reforming social renting Chapter 7 Chapter 5 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 Reforming social renting 102 Reforming private renting p86 p90 Chapter 8 112 Building more social housing Recommendations 138 Recommendations Chapter 7 Reforming private renting Chapter 8 Building more social housing Recommendations p102 p112 p138 4 Building for our future: a vision for social housing 5 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Foreword Foreword Foreword Reverend Dr Mike Long, Chair of the commission In January 2018, the housing and homelessness charity For social housing to work as it should, a broad political Shelter brought together sixteen commissioners from consensus is needed. -

Measuring the Exposure of Black, Asian and Other Ethnic Groups to Covid-Infected Neighbourhoods in English Towns and Cities Rich

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.04.21252893; this version posted March 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Measuring the exposure of Black, Asian and other ethnic groups to Covid-infected neighbourhoods in English towns and cities Richard Harris*, School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, University Road, Bristol. BS8 1SS, UK. [email protected] Chris Brunsdon, National Centre for Geocomputation, Maynooth University, Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland. [email protected] Abstract Drawing on the work of The Doreen Lawrence Review – a report on the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities in the UK – this paper develops an index of exposure, measuring which ethnic groups have been most exposed to Covid-19 infected residential neighbourhoods during the first and second waves of the pandemic in England. The index is based on a Bayesian Poisson model with a random intercept in the linear predictor, allowing for extra-Poisson variation at neighbourhood and town/city scales. This permits within-city differences to be decoupled from broader regional trends in the disease. The research finds that members of ethnic minority groups tend to be living in areas with higher infection rates but also that the risk of exposure is distributed unevenly across these groups. Initially, in the first wave, the disease disproportionately affected Black residents. -

Bus Services from Lewisham

River Thames to Broadwaters and Belmarsh Prison 380 Bus services from Lewisham Plumstead Bus Garage Woolwich for Woolwich Arsenal Station 180 122 to Abbey Wood, Thamesmead East 54 and Belvedere Moorgate 21 47 N 108 Finsbury Square Industrial Area Shoreditch Stratford Bus Station Charlton Anchor & Hope Lane Woolwich Bank W E Dockyard Bow Bromley High Street Liverpool Street 436 Paddington East Greenwich Poplar North Greenwich Vanbrugh Hill Blackwall Tunnel Woolwich S Bromley-by-Bow Station Eastcombe Charlton Common Monument Avenue Village Edgware Road Trafalgar Road Westcombe Park Sussex Gardens River Thames Maze Hill Blackheath London Bridge Rotherhithe Street Royal Standard Blackheath Shooters Hill Marble Arch Pepys Estate Sun-in-the-Sands Police Station for London Dungeon Holiday Inn Grove Street Creek Road Creek Road Rose Creekside Norman Road Rotherhithe Bruford Trafalgar Estate Hyde Park Corner Station Surrey College Bermondsey 199 Quays Evelyn Greenwich Queens House Station Street Greenwich Church Street for Maritime Museum Shooters Hill Road 185 Victoria for Cutty Sark and Greenwich Stratheden Road Maritime Museum Prince Charles Road Cutty Sark Maze Hill Tower 225 Rotherhithe Canada Deptford Shooters Hill Pimlico Jamaica Road Deptford Prince of Wales Road Station Bridge Road Water Sanford Street High Street Greenwich Post Office Prince Charles Road Bull Druid Street Church Street St. Germans Place Creek Road Creek Road The Clarendon Hotel Greenwich Welling Borough Station Pagnell Street Station Montpelier Row Fordham Park Vauxhall -

Green Chain Walk – Section 6 of 11

Transport for London.. Green Chain Walk. Section 6 of 11. Oxleas Wood to Mottingham. Section start: Oxleas Wood. Nearest stations Oxleas Wood (bus stop on Shooters Hill / A207) to start: or Falconwood . Section finish: Mottingham. Nearest stations Mottingham to finish: Section distance: 3.7 miles (6.0 kilometres). Introduction. Walk in the footsteps of royalty as you pass Eltham Palace and the former hunting grounds of the Tudor monarchs who resided there. The manor of Eltham came into royal possession on the death of the Bishop of Durham in 1311. The parks were enclosed in the 14th Century and in 1364 John II of France yielded himself to voluntary exile here. In 1475 the Great Hall was built on the orders of Edward IV and the moat bridge probably dates from the same period. Between the reigns of Edward IV and Henry VII the Palace reached the peak of its popularity, thereafter Tudor monarchs favoured the palace at Greenwich. Directions. To reach the start of this section from Falconwood Rail Station, turn right on to Rochester Way and follow the road to Oxleas Wood. Enter the wood ahead and follow the path to the Green Chain signpost. Alternatively, take bus route 486 or 89 to Oxleas Wood stop and take the narrow wooded footpath south to reach the Green Chain signpost. From the Green Chain signpost in the middle of Oxleas Wood follow the marker posts south turning left to emerge at the junction of Welling Way and Rochester Way. Cross Rochester Way at the traffic lights and enter Shepherdleas Wood. -

An Independent Study, the Future of Artists and Architecture? Screening Programme, Selected by Vanessa Scully 19 October 2019

Thamesmead Texas presents: An independent study, the future of artists and architecture? Screening programme, selected by Vanessa Scully 19 October 2019 Thamesmead Texas presents a selection of experimental and documentary films on social housing, gentrification and regeneration from the 1970’s – present day London. Selected by artist Vanessa Scully, as part of the series ‘Thamesmead Texas presents: An independent study, the future of artists and architecture? This screening event sits within a new installation entitled ‘Heavy View’ by British Artist Laura Yuile that developed out of Yuile’s consideration of technological and architectural obsolescence. TACO!, 30 Poplar Place, Thamesmead, London SE28 8BA. Saturday 19 October, 7-10pm. Part One: Meanwhile space in London*, shorts Katharine Meynell, Kissing (2014), 3:00 mins, digital video John Smith, Dungeness (1987) 3:35 mins, 16mm film William Raban, Cripps at Acme (1981), 5:35 mins, 16mm film Wendy Short, Overtime (2016), 10:09 mins, digital video Channel 4, Home Truths – Art and Soul (2014), 4:51 mins, digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v1 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v2 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v3 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video John Smith & Jocelyn Pook, Blight (1996), 16 mins, 16mm film Part Two: A history of social housing in London, feature Tom Cordell, Utopia London (2010), 82 mins, digital video and archive material Tessa Garland, Here East (2017), 5:42 mins, HD video Part One: into his thirties) a figure to add to the pantheon of profoundly subversive, wildly misbehaved, and Katharine Meynell, Kissing (2014) perhaps genuinely unhinged twentieth-century artists, alongside Jack Smith, Harry Smith, Kenneth “Made in response to a word drawn from a hat with Anger, Chris Burden, Joe Coleman, and others.” LUX 13 Critical Forum, I kissed the iconic Balfron Jared Rap-fogelVol. -

Mottingham Station

Mottingham Station On the instruction of London and South Eastern Railway Limited Retail Opportunity On the instruction of LSER Retail Opportunity MOTTINGHAM STATION SE9 4EN The station is served by services operated by Southeastern to London Charing Cross, London Cannon Street, Woolwich Arsenal and Dartford. The station is located in the town on Mottingham. Location Rent An opportunity exists to let a unit at the front of We are inviting offers for this temporary opportunity. Mottingham railway station on Station Approach. Business plans detailing previous experience with visuals should be submitted with the financial offer. Description The unit is approximately 220sq ft and has 32amp power. The site does not have water & drainage and Business Rates is not suitable for catering. The tenant shall be responsible for business rates. A Information from the Office of the Rail Regulator search for the Rateable Value using the station stipulates that in 2019/20 there were over 1.322 postcode and the Valuation Office Agency website has million passenger entries and exits per annum. not provided any detail. It is recommended that interested parties make their own enquiries with the Local Authority to ascertain what business rates will Agreement Details be payable. We are inviting offers from retailers looking to trade Local Authority is London Borough of Greenwich. on a temporary basis documented by a Tenancy at Will. Other Costs The tenant will be responsible for all utilities, business We are not able to discuss longer term potential rates and insurance. currently. The Tenancy at Will will cost £395 plus vat. AmeyTPT Limited and their clients give notice that: (i) These particulars do not form part of any offer or contract and must not be relied upon as statements or representations of fact. -

CHECK BEFORE YOU TRAVEL at Nationalrail.Co.Uk

Changes to train times Monday 7 to Sunday 13 October 2019 Planned engineering work and other timetable alterations King’s Lynn Watlington Downham Market Littleport 1 Ely Saturday 12 and Sunday 13 October Late night and early morning alterations 1 ! Waterbeach All day on Saturday and Sunday Late night and early morning services may also be altered for planned Peterborough Cambridge North Buses replace trains between Cambridge North and Downham Market. engineering work. Plan ahead at nationalrail.co.uk if you are planning to travel after 21:00 or Huntingdon Cambridge before 06:00 as train times may be revised and buses may replace trains. Sunday 13 October St. Neots Foxton Milton Keynes Bedford 2 Central Shepreth Until 08:30 on Sunday Sandy Trains from London will not stop at Harringay, Hornsey or Alexandra Palace. Meldreth Replacement buses will operate between Finsbury Park and New Barnet, but Flitwick Biggleswade Royston Bletchley will not call at Harringay or Hornsey. Please use London buses. Ashwell & Morden Harlington Arlesey Baldock Leighton Buzzard Leagrave Letchworth Garden City Sunday 13 October Hitchin Luton 3 Until 09:45 on Sunday Stevenage Tring Watton-at-Stone Key to colours Buses replace trains between Alexandra Palace and Stevenage via Luton Airport Parkway Luton Knebworth Hertford North. Airport Hertford North No trains for all or part of A reduced service will operate between Moorgate and Alexandra Palace. Welwyn North Berkhamsted Harpenden Bayford Welwyn Garden City the day. Replacement buses Cuffley 3 St. Albans City Hatfield Hemel Hempstead may operate. Journey times Sunday 13 October Kentish Town 4 Welham Green Crews Hill will be extended. -

Our Community, a Walk Through Bellingham, Downham and Whitefoot

OUR COMMUNITY A walk through Bellingham, Downham and Whitefoot Residents’ Annual Report 2013-14 3 WELCOME… OTHER LANDLORDS We’re pleased to introduce your Phoenix and hear what’s planned to improve Do make sure to visit our website residents’ annual report for 2013-14. Join us our community even more over the next www.phoenixch.org.uk to read the digital Throughout this report we compare our CONTENTS on a walk through our community. 12 months. version of this report, which includes lots of performance against other medium- additional information and videos. sized housing associations (5,000-10,000 OUR COMMUNITY GATEWAY Page 4 We’ve listened to your feedback from last It’s impossible to include EVERYTHING properties) in London and the south east OUR HOMES Page 8 year’s annual report and worked hard to that goes on within this report, so we’ve Finally, if you care about the future of our and nationally. This information comes make this year’s even better. highlighted the things that we feel are area and the community, we’d love to hear from Housemark, an organisation that OUR COMMUNITY Page 12 Phoenix is all of us. Our homes, our streets, the most important. We’ve examined our from you. Please join us as we work towards gathers performance information from OUR MONEY Page 16 our green spaces, tenants, leaseholders and performance against our agreed standards our vision of a better future for all. lots of other housing associations. OUR FUTURE Page 20 and we’re pleased to be able to say that we staff alike. -

Buses from North Greenwich Bus Station

Buses from North Greenwich bus station Route finder Day buses including 24-hour services Stratford 108 188 Bus Station Bus route Towards Bus stops Russell Square 108 Lewisham B for British Museum Stratford High Street Stratford D Carpenters Road HOLBORN STRATFORD 129 Greenwich C Holborn Bow River Thames 132 Bexleyheath C Bromley High Street 161 Chislehurst A Aldwych 188 Russell Square C for Covent Garden Bromley-by-Bow and London Transport Museum 422 Bexleyheath B River Thames Coventry Cross Estate The O2 472 Thamesmead A Thames Path North CUTTER LANE Greenwich 486 Bexleyheath B Waterloo Bridge Blackwall Tunnel Pier Emirates East india Dock Road for IMAX Cinema, London Eye Penrose Way Royal Docks and Southbank Centre BLACKWALL TUNNEL Peninsula Waterloo Square Pier Walk E North Mitre Passage Greenwich St George’s Circus D B for Imperial War Museum U River Thames M S I S L T C L A E T B A N I Elephant & Castle F ON N Y 472 I U A W M Y E E Thamesmead LL A Bricklayers Arms W A S Emirates Air Line G H T Town Centre A D N B P Tunnel Y U A P E U R Emirates DM A A S E R W K Avenue K S S Greenwich Tower Bridge Road S T A ID Thamesmead I Y E D Peninsula Crossway Druid Street E THAMESMEAD Bermondsey Thamesmead Millennium Way Boiler House Canada Water Boord Street Thamesmead Millennium Greenwich Peninsula Bentham Road Surrey Quays Shopping Centre John Harris Way Village Odeon Cinema Millennium Primary School Sainsbury’s at Central Way Surrey Quays Blackwall Lane Greenwich Peninsula Greenwich Deptford Evelyn Street 129 Cutty Sark WOOLWICH Woolwich -

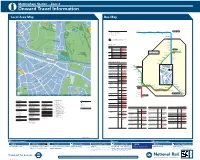

Local Area Map Bus Map

Mottingham Station – Zone 4 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 58 23 T 44 N E Eltham 28 C S E R 1 C Royalaal BlackheathBl F F U C 45 E D 32 N O A GolfG Course R S O K R O L S B I G L A 51 N 176 R O D A T D D H O A Elthamam 14 28 R E O N S V A L I H S T PalacPPalaceaala 38 A ROA 96 126 226 Eltham Palace Gardens OURT C M B&Q 189 I KINGSGROUND D Royal Blackheath D Golf Club Key North Greenwich SainsburyÕs at Woolwich Woolwich Town Centre 281 L 97 WOOLWICH 2 for Woolwich Arsenal E Ø— Connections with London Underground for The O Greenwich Peninsula Church Street P 161 79 R Connections with National Rail 220 T Millennium Village Charlton Woolwich A T H E V I S TA H E R V Î Connections with Docklands Light Railway Oval Square Ferry I K S T Royaloya Blackheathack MMiddle A Â Connections with river boats A Parkk V Goolf CourseCo Connections with Emirates Air Line 1 E 174 N U C Woolwich Common Middle Park E O Queen Elizabeth Hospital U Primary School 90 ST. KEVERNEROAD R T 123 A R Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus 172 O Well Hall Road T service. The disc !A appears on the top of the bus stop in the E N C A Arbroath Road E S King John 1 2 3 C R street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). -

COVID-19 Vaccination Pop-Up Clinics in South-East London

COVID-19 vaccination pop-up clinics in south-east London If you are eligible for a COVID vaccination, you can get your COVID vaccination from a number of walk- in and pop-up clinics this week. You can also find the latest information on our website at selondonccg.nhs.uk/popupclinics • Page 1 – SEL-wide, Bexley, Bromley • Page 2 – Greenwich, Lambeth • Page 3 – Lewisham, Southwark Borough Location Day Time Booking information Further information For +18s – Pfizer and AstraZeneca. Second Burfoot Court Room, doses are available for people age 40 and Counting House at older who had their first dose at least eight Daily, throughout Walk-in, no appointment Guy’s Hospital, Great 8:00am-7:00pm weeks ago, and for people under 40 who had June needed Maze Pond, London their first dose 12 weeks ago.You do not SE1 9RT need proof of address, immigration status, ID or an NHS number. For +18s – Pfizer. Second doses are available for people age 40 and older who St Thomas’ Hospital, had their first dose at least eight weeks ago, Daily, throughout Walk-in, no appointment Westminster Bridge Rd, 8:00am-7:00pm and for people under 40 who had their first June needed. London, SE1 7EH dose 12 weeks ago.You do not need proof All SEL of address, immigration status, ID or an residents NHS number. welcome Walk-in, no appointment needed. First doses or second doses after 8-week interval if aged Montgomery Hall, 58 See SEL CCG over 40, 12 weeks if under 40. See SEL CCG Walk-in, no appointment Kennington Oval, SE11 Daily from 2-19 July website for exact website for which days are for +18, and needed. -

Guest Speaker: Lord Victor Adebowale CBE from Stephen Lawrence to Grenfell – 20 Years for Race Equality

Guest Speaker: Lord Victor Adebowale CBE From Stephen Lawrence to Grenfell – 20 years for Race Equality Thank you for joining us today to celebrate this milestone with us – 20 years of Race on the Agenda. So I’m going to talk for 20 minutes – 1 minute for each year – so you won’t have to listen to me witter on for too long. I promise I’ll keep to time so we can get on to the reception. Don’t want to see you all looking at your watches. Change has not been linear ROTA has spent the last 20 years fighting to bring the issues that impact BAME people into focus – working to reduce online hate speech, researching young girls and gangs and equipping third sector organisations with a comprehensive understanding of the Equality Act. The change has not been linear – we’ve faced roadblocks, successive governments and I’ve seen more ‘Race’ reviews than I’ve listened to Stevie Wonder albums. But is the arc for Race Equality bending towards justice in the overall? It’s hard to say. In 2009, 10 years on from the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, an Ipsos MORI poll for the Equality and Human Rights Commission showed us a country more at ease with itself than ever before – a nation where nearly half of its citizens were optimistic Britain would be more tolerant in 10 years’ time. Back then - 58% of ethnic minorities were optimistic about the future. Would 58% of ethnic minorities say the same today? I doubt it. Now our reality is quite different.