Re-Envisioning the Rising: Irish Literary Memories of 1916

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

A Comparative Study of Extremism Within Nationalist Movements

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EXTREMISM WITHIN NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND SPAIN by Ashton Croft Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of History Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas 22 April 2019 Croft 1 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EXTREMISM WITHIN NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND SPAIN Project Approved: Supervising Professor: William Meier, Ph.D. Department of History Jodi Campbell, Ph.D. Department of History Eric Cox, Ph.D. Department of Political Science Croft 2 ABSTRACT Nationalism in nations without statehood is common throughout history, although what nationalism leads to differs. In the cases of the United Kingdom and Spain, these effects ranged in various forms from extremism to cultural movements. In this paper, I will examine the effects of extremists within the nationalism movement and their overall effects on societies and the imagined communities within the respective states. I will also compare the actions of extremist factions, such as the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA), and the Scottish National Liberation Army (SNLA), and examine what strategies worked for the various nationalist movements at what points, as well as how the movements connected their motives and actions to historical memory. Many of the groups appealed to a wider “imagined community” based on constructing a shared history of nationhood. For example, violence was most effective when it directly targeted oppressors, but it did not work when civilians were harmed. Additionally, organizations that tied rhetoric and acts back to actual histories of oppression or of autonomy tended to garner more widespread support than others. -

Collection List A19

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List 19 Augustine Henry and Evelyn Gleeson Papers (MS 13,698) (Accession 2501) Partial calendar with brief description of letters sent by Augustine Henry and Evelyn Gleeson between 1879 and 1928. Letters are arranged according to year and date. 1 Introduction Henry, Augustine (1857–1930), botanical collector and dendrologist, was born on 2 July 1857 in Dundee, the first of six children of Bernard Henry (c.1825–1891) and Mary MacNamee. His father, at one time a gold-prospector in California and Australia, was a native of the townland of Tyanee on the west bank of the River Bann in co. Londonderry. Soon after Austin (as Augustine was called within his family) was born, the family moved to Cookstown, co. Tyrone, where his father was in business as a flax dealer and owned a grocery shop. Henry was educated at Cookstown Academy and in Queen's College, Galway. He studied natural sciences and philosophy, graduating with a first-class bachelor of arts degree and a gold medal in 1877. Henry then studied medicine at Queen's College, Belfast, where he obtained his master of arts degree in 1878. For a year he was in the London Hospital, and during a visit to Belfast in 1879, at the suggestion of one of his professors, he applied for a medical post in the Chinese imperial maritime customs service. Henry completed his medical studies as rapidly as he could, became a licentiate from the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh, passed the Chinese customs service examinations (for which he required a working knowledge of Chinese) and and left for China in the summer of 1881. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

POLITICAL PARODY and the NORTHERN IRISH PEACE PROCESS Ilha Do Desterro: a Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, Núm

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Phelan, Mark (UN)SETTLEMENT: POLITICAL PARODY AND THE NORTHERN IRISH PEACE PROCESS Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 191-215 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative (Un)Settlement: Political Parody and... 191 (UN)SETTLEMENT: POLITICAL PARODY AND THE NORTHERN IRISH PEACE PROCESS 1 Mark Phelan Queen’s University Belfast Human beings suffer, They torture one another, They get hurt and get hard No poem or play or song Can fully right a wrong Inflicted and endured... History says, Don’t hope On this side of the grave. But then, once in a lifetime The longed-for tidal wave Of justice can rise up, And hope and history rhyme. (Heaney, The Cure at Troy 77) Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 58 p. 191-215 jan/jun. 2010 192 Mark Phelan Abstract: This essay examines Tim Loane’s political comedies, Caught Red-Handed and To Be Sure, and their critique of the Northern Irish peace process. As “parodies of esteem”, both plays challenge the ultimate electoral victors of the peace process (the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Féin) as well as critiquing the cant, chicanery and cynicism that have characterised their political rhetoric and the peace process as a whole. -

The Historical Development of Irish Euroscepticism to 2001

The Historical Development of Irish Euroscepticism to 2001 Troy James Piechnick Thesis submitted as part of the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) program at Flinders University on the 1st of September 2016 Social and Behavioural Sciences School of History and International Relations Flinders University 2016 Supervisors Professor Peter Monteath (PhD) Dr Evan Smith (PhD) Associate Professor Matt Fitzpatrick (PhD) Contents GLOSSARY III ABSTRACT IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 DEFINITIONS 2 PARAMETERS 13 LITERATURE REVIEW 14 MORE RECENT DEVELOPMENTS 20 THESIS AND METHODOLOGY 24 STRUCTURE 28 CHAPTER 2 EARLY ANTECEDENTS OF IRISH EUROSCEPTICISM: 1886–1949 30 IRISH REPUBLICANISM, 1780–1886 34 FIRST HOME RULE BILL (1886) AND SECOND HOME RULE BILL (1893) 36 THE BOER WAR, 1899–1902 39 SINN FÉIN 40 WORLD WAR I AND EASTER RISING 42 IRISH DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 46 IRISH WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1919 AND CIVIL WAR 1921 47 BALFOUR DECLARATION OF 1926 AND THE STATUTE OF WESTMINSTER IN 1931 52 EAMON DE VALERA AND WORLD WAR II 54 REPUBLIC OF IRELAND ACT 1948 AND OTHER IMPLICATIONS 61 CONCLUSION 62 CHAPTER 3 THE TREATY OF ROME AND FAILED APPLICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN 1961 AND 1967 64 THE TREATY OF ROME 67 IRELAND IN THE 1950S 67 DEVELOPING IRISH EUROSCEPTICISM IN THE 1950S 68 FAILED APPLICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN 1961 AND 1967 71 IDEOLOGICAL MAKINGS: FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS OF A EUROSCEPTIC NATURE (1960S) 75 Communist forms of Irish euroscepticism 75 Irish eurosceptics and republicanism 78 Irish euroscepticism accommodating democratic socialism 85 -

Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles

Irish Communication Review Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 6 July 2020 Posters, Handkerchiefs and Murals: Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles Bradley Rohlf Mount Aloysius College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr Part of the Communication Commons, History of Gender Commons, Visual Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rohlf, Bradley (2020) "Posters, Handkerchiefs and Murals: Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles," Irish Communication Review: Vol. 17: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol17/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Current Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Communication Review by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Irish Communications Review vol 17 (2020) Posters, handkerchiefs and murals: Visual gender separation during the Troubles Bradley Rohlf, Mount Aloysius College (Pennsylvania) Abstract The Troubles in Northern Ireland provide a complex and intriguing topic for many scholars in various academic disciplines. Their violence, publicity and tragedy are common themes that elicit a plethora of emotional responses throughout the world. However, the very intimate nature of this conflict creates a much more complex system of friends, foes and experiences for those involved. While the very heart of the Irish nationalist movement is founded on liberal and progressive concepts such as socialism and equality, the media associated with it sometimes promote tradition and conservatism, especially regarding gender. -

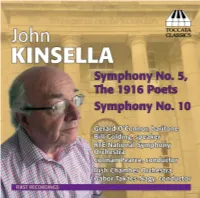

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

April 2016 Ianohio.Com 2 IAN Ohio “We’Ve Always Been Green!” APRIL 2016

April 2016 ianohio.com 2 IAN Ohio “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com APRIL 2016 Ancient Order of Hibernians Division Installs Triplet Sons of Charter Member The Amsden Triplets, from left: Alex, Father- Eric, David & Luke The Irish Brigade Division #1 of Medina are juniors at Midview High School in County Charter Member Eric Amsden Grafton, Ohio. brought his seventeen year old triplet sons to be installed in the division. Eric The division is always glad to see the was able to lead his sons in the pledge of sons of members join, but was especially the Order. The newest Hibernians are pleased to have this unique Alex, David and Luke Amsden. All three experience happen. West Side Irish American Club Upcoming Events: Live Music & Food in The Pub every Friday 6th – Wine Tasting 23rd – 1916 Easter Rising Centennial Celebration 24th – Annual Style Show & Luncheon General Meeting 3rd Thursday of every month. Since 1931 8559 Jennings Road Olmsted, Twp, Ohio 44138 440.235.5868 www.wsia-club.org APRIL 2016 “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com 3 One of my favorite people is and breaks we have received. To Editor’s Corner Pulitzer Prize winning author and those that paved the path, that columnist Regina Brett. She writes planted seeds or nurtured their with and of common sense, caring, growing, to those who received leaving the judgement at the door the honors and the appreciation, in a life well-lived and the lessons and those who did it without any learned. She says in her book, God recognition at all, I wish to say, Never Blinks, “People don’t want Thank you. -

2001-; Joshua B

The Irish Labour History Society College, Dublin, 1979- ; Francis Devine, SIPTU College, 1998- ; David Fitzpat- rick, Trinity College, Dublin, 2001-; Joshua B. Freeman, Queen’s College, City Honorary Presidents - Mary Clancy, 2004-; Catriona Crowe, 2013-; Fergus A. University of New York, 2001-; John Horne, Trinity College, Dublin, 1982-; D’Arcy, 1994-; Joseph Deasy, 2001-2012; Barry Desmond, 2013-; Francis Joseph Lee, University College, Cork, 1979-; Dónal Nevin, Dublin, 1979- ; Cor- Devine, 2004-; Ken Hannigan, 1994-; Dónal Nevin, 1989-2012; Theresa Mori- mac Ó Gráda, University College, Dublin, 2001-; Bryan Palmer, Queen’s Uni- arty, 2008 -; Emmet O’Connor, 2005-; Gréagóir Ó Dúill, 2001-; Norah O’Neill, versity, Kingston, Canada, 2000-; Henry Patterson, University Of Ulster, 2001-; 1992-2001 Bryan Palmer, Trent University, Canada, 2007- ; Bob Purdie, Ruskin College, Oxford, 1982- ; Dorothy Thompson, Worcester, 1982-; Marcel van der Linden, Presidents - Francis Devine, 1988-1992, 1999-2000; Jack McGinley, 2001-2004; International Institute For Social History, Amsterdam, 2001-; Margaret Ward, Hugh Geraghty, 2005-2007; Brendan Byrne, 2007-2013; Jack McGinley, 2013- Bath Spa University, 1982-2000. Vice Presidents - Joseph Deasy, 1999-2000; Francis Devine, 2001-2004; Hugh Geraghty, 2004-2005; Niamh Puirséil, 2005-2008; Catriona Crowe, 2009-2013; Fionnuala Richardson, 2013- An Index to Saothar, Secretaries - Charles Callan, 1987-2000; Fionnuala Richardson, 2001-2010; Journal of the Irish Labour History Society Kevin Murphy, 2011- & Assistant Secretaries - Hugh Geraghty, 1998-2004; Séamus Moriarty, 2014-; Theresa Moriarty, 2006-2007; Séan Redmond, 2004-2005; Fionnuala Richardson, Other ILHS Publications, 2001-2016 2011-2012; Denise Rogers, 1995-2007; Eddie Soye, 2008- Treasurers - Jack McGinley, 1996-2001; Charles Callan, 2001-2002; Brendan In September, 2000, with the support of MSF (Manufacturing, Science, Finance – Byrne, 2003-2007; Ed.