Ashesi University the Fundamental Problem of the Ghanaian Football League

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOAL!January/February 2013 2013 We Have the Tools Orange and the Momentum

One team. One goal. United, we can beat malaria. United Against Malaria GOAL!January/February 2013 2013 We have the tools Orange and the momentum. Now we need Africa you! Cup of Nations tournament Gervinho’s gift fixture inside CAF vs. Malaria quiz, interviews, + exclusive photos and A president gets tips from the pros on how the “Golden Boot” to beat malaria Africa’s biggest Didier Drogba stars unite to Côte d’Ivoire team captain, UAM champion kick out malaria 2013 Orange Africa Cup of Nations Edition www.UnitedAgainstMalaria.org ONE UNITED, TEAM. WE CAN ONE BEAT GOAL. MALARIA. Seydou Keita Mali footballer and UAM champion UAM fans Mali Malaria is a disease caused by parasites transmitted to humans through the bite of an Anopheles mosquito. If left untreated, its flu-like symptoms—fever, headache, fatigue, shivering, nausea and vomiting—can lead to coma and death. Founded ahead of the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, United Approximately half of the world’s population is at risk of malaria. Against Malaria (UAM) is an alliance of football teams, celebrities, Malaria kills a child in Africa every minute and nearly 655,000 health and advocacy organizations, governments and corporations people annually. More than 90% of malaria deaths occur in that have united together against malaria. As part of the Roll Back Africa, mostly children under five years of age. Malaria costs the Malaria (RBM) Partnership, UAM is made up of over 200 partners continent at least US $12 billion in lost productivity every year. from diverse sectors and continents who invest their experience, Malaria is preventable and treatable. -

Football League Tables 29 April

Issued Date Page England Top Leagues 2019 - 2020 29/04/2021 10:45 1/66 England - Premier League 20/21 England - Championship 20/21 P T Team PL W D L GH W D L GA W D L GT PT Last RES P T Team PL W D L GH W D L GA W D L GT PT Last RES 1 ● MAN. CITY 33 24 5 4 69:24 12 2 3 37:15 12 3 1 32:9 77 Cl L W W 1 ● NORWICH 44 28 9 7 69:33 13 6 3 35:14 15 3 4 34:19 93 Pro D W W 2 ● MAN. UTD 33 19 10 4 64:35 9 3 4 34:21 10 7 0 30:14 67 Cl W W W 2 ● WATFORD 44 26 10 8 61:28 18 2 2 42:12 8 8 6 19:16 88 Pro W D W 3 ● LEICESTER 33 19 5 9 60:38 9 1 7 30:22 10 4 2 30:16 62 Cl W W L 3 ● BRENTFORD FC 44 22 15 7 74:41 11 9 2 37:20 11 6 5 37:21 81 Pro Pl D W D 4 ● CHELSEA 33 16 10 7 51:31 7 6 3 27:16 9 4 4 24:15 58 Cl W D L 4 ● BOURNEMOUTH 44 22 11 11 73:43 13 3 6 40:22 9 8 5 33:21 77 Pro Pl W W W 5 ● WEST HAM 33 16 7 10 53:43 9 4 4 29:21 7 3 6 24:22 55 Uefa L D W 5 ● SWANSEA 44 22 11 11 54:36 11 6 5 25:15 11 5 6 29:21 77 Pro Pl L W W 6 ● LIVERPOOL 33 15 9 9 55:39 8 3 6 25:20 7 6 3 30:19 54 L W W 6 ● BARNSLEY 44 23 8 13 56:46 12 5 5 28:20 11 3 8 28:26 77 Pro Pl D W W 7 ● TOTTENHAM 33 15 8 10 56:38 8 3 5 28:18 7 5 5 28:20 53 L W D 7 ● READING 44 19 12 13 59:48 12 3 7 35:25 7 9 6 24:23 69 D W L 8 ● EVERTON 32 15 7 10 44:40 5 4 7 22:25 10 3 3 22:15 52 L L D 8 ▼ CARDIFF CITY 44 17 13 14 61:48 8 5 9 36:25 9 8 5 25:23 64 L L D 9 ▼ LEEDS 33 14 5 14 50:50 6 5 6 22:19 8 0 8 28:31 47 D W W 9 ▼ MIDDLESBROUGH 44 18 9 17 54:49 11 4 7 30:22 7 5 10 24:27 63 L D L 10 ▲ ARSENAL 33 13 7 13 44:37 6 4 7 19:20 7 3 6 25:17 46 W D L 10 ▲ Q.P.R. -

Das Grosse Vereinslexikon Des Weltfussballs

1 RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS ALLE ERSTLIGISTEN WELTWEIT VON 1885 BIS HEUTE AFRIKA & ASIEN BAND 1 DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS DES VEREINSLEXIKON GROSSE DAS BAND 1 AFRIKA & ASIEN RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS BAND 1 AFRIKA UND ASIEN Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National- bibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Copyright © 2019 Verlag Die Werkstatt GmbH Lotzestraße 22a, D-37083 Göttingen, www.werkstatt-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Gestaltung: René Köber Satz: Die Werkstatt Medien-Produktion GmbH, Göttingen ISBN 978-3-7307-0459-2 René Köber RENÉRené KÖBERKöber Das große Vereins- DasDAS große GROSSE Vereins- LEXIKON VEREINSLEXIKONdesL WEeXlt-IFKuOßbNal lS des Welt-F ußballS DES WELTFUSSBALLSBAND 1 BAND 1 BAND 1 AFRIKAAFRIKA UND und ASIEN ASIEN AFRIKA und ASIEN Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute 15 00015 000 Vereine Vereine aus aus 6 6 000 000 Städten/Ortschaften und und 228 228 Ländern Ländern 15 000 Vereine aus 6 000 Städten/Ortschaften und 228 Ländern 1919 000 000 farbige Vereinslogos Vereinslogos 19 000 farbige Vereinslogos Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Stadien, Erfolge, Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Spielerauswahl Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, -

England Top Leagues 2019 - 2020 15/11/2020 09:45 1/31

Issued Date Page England Top Leagues 2019 - 2020 15/11/2020 09:45 1/31 England - Premier League 2020/21 England - Championship 2020/21 P T Team PL W D L GH W D L GA W D L GT PT Last RES P T Team PL W D L GH W D L GA W D L GT PT Last RES 1 ▲ LEICESTER CITY FC 8 6 0 2 18:9 2 0 2 5:6 4 0 0 13:3 18 Champions L.. W W W 1 ● READING FC 11 7 1 3 17:12 4 0 2 7:6 3 1 1 10:6 22 Promotion L L L 2 ▲ TOTTENHAM HOTSPU.. 8 5 2 1 19:9 1 2 1 6:6 4 0 0 13:3 17 Champions L.. W W W 2 ▲ WATFORD FC 11 6 3 2 14:9 5 1 0 12:6 1 2 2 2:3 21 Promotion W W L 3 ▼ LIVERPOOL FC 8 5 2 1 18:16 4 0 0 11:6 1 2 1 7:10 17 Champions L.. D W W 3 ● NORWICH CITY FC 11 6 3 2 13:8 3 2 1 6:4 3 1 1 7:4 21 Prom Poffs W D W 4 ▲ SOUTHAMPTON FC 8 5 1 2 16:12 3 0 1 8:5 2 1 1 8:7 16 Champions L.. W W W 4 ▲ AFC BOURNEMOUTH 11 5 5 1 15:9 3 2 0 6:3 2 3 1 9:6 20 Prom Poffs W L D 5 ▲ CHELSEA FC 8 4 3 1 20:10 2 1 1 11:6 2 2 0 9:4 15 Europa Leag. -

Fair Play 1964-2005 INGLESE

Fair Play Trophies et Diplomas awarded by IFPC from 1964 to 2005 Winners Publication edited in agreement with the International Committee for Fair Play Panathlon International Villa Porticciolo – Via Maggio, 6 16035 Rapallo - Italie www.panathlon.net e-mail: [email protected] project and cultural coordination International Committee for Fair Play Panathlon International works coordinators Jean Durry Siropietro Quaroni coordination assistants Nicoletta Bena Emanuela Chiappe page layout and printing: Azienda Grafica Busco - Rapallo 2 Contents Jeno Kamuti 5 The "Fair Play", its sense and its winners Enrico Prandi 8 “Angel or Demon? The choise of Fair Play” Definition and History 11 of the International Committee for Fair Play Antonio Spallino 25 Panathlon International and the promotion of Fair Play Fair Play World Trophies Trophies and Diplomas 33 awarded by International Committee for Fair play from the origin Letters of congratulations 141 Nations legend 150 Disciplines section 155 Alphabethical index 168 3 Jeno Kamuti President of the International Fair Play Committee The “Fair Play”, its sense and its winners Nowadays, at the beginning of the XXIst century, sport has finally earned a worthy place in the hier - archy of society. It has become common wisdom that sport is not only an activity assuring physical well-being, it is not only a phenomenon carrying and reinforcing human values while being part of general culture, but that it is also a tool in the process of education, teaching and growing up to be an upright individ - ual. Up until now, we have mostly contented our - selves with saying that sport is a mirror of human activities in society. -

Political Discourse in Football Coverage – the Cases of Côte D’Ivoire and Ghana

GIGA Research Unit: Institute of African Affairs ___________________________ Political Discourse in Football Coverage – The Cases of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana Andreas Mehler N° 27 August 2006 www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers GIGA-WP-27/2006 GIGA Working Papers Edited by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien. The Working Paper Series serves to disseminate the research results of work in progress prior to publication to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. Inclusion of a paper in the Working Paper Series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. Copyright remains with the authors. When Working Papers are eventually accepted by or published in a journal or book, the correct citation reference and, if possible, the corresponding link will then be included in the Working Papers website at: www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers. GIGA research unit responsible for this issue: Research Unit: Institute of African Affairs. Editor of the GIGA Working Paper Series: Bert Hoffmann <[email protected]> Copyright for this issue: © Andreas Mehler Editorial assistant and production: Verena Kohler All GIGA Working Papers are available online and free of charge at the website: www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers. Working Papers can also be ordered in print. For production and mailing a cover fee of € 5 is charged. For orders or any requests please contact: e-mail: [email protected] phone: ++49 (0)40 - 428 25 548 GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies / Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien Neuer Jungfernstieg 21 20354 Hamburg Germany E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.giga-hamburg.de GIGA-WP-27/2006 Political Discourse in Football Coverage – The Cases of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana Abstract Football coverage in newspapers is both an arena for and a mirror of political discourse within a society. -

Release List of up to 30 Players

Release list of up to 30 players Each association’s release list of up to 30 players was received by 11 May 2010 as per article 26 of the Regulations for the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa™. Mandatory rest period for players on the release list is from 17-23 May 2010 (except players involved in the UEFA Champions League final on 22 May). Each association must send FIFA a final list of no more than 23 players by 24.00 CET on 1 June 2010. Final list is limited to players on the release list submitted on 11 May 2010. Final list of 23 players will be published on FIFA.com at 12.00 CET on 4 June. Injured players may be replaced up to 24 hours before a team’s first match. Replacement players are not limited to the release list of up to 30 players. Liste de joueurs à libérer Les listes de joueurs à libérer (comportant jusqu’à 30 joueurs) ont été reçues de chaque association membre participante avant le 11 mai 2010 conformément à l’art. 26 du Règlement de la Coupe du Monde de la FIFA, Afrique du Sud 2010. La période de repos obligatoire à observer par les joueurs figurant sur la liste de joueurs à libérer (à l’exception des joueurs participant à la finale de la Ligue des Champions de l’UEFA le 22 mai) est du 17 au 23 mai 2010. Chaque association doit envoyer à la FIFA une liste définitive comportant un maximum de 23 joueurs au plus tard le 1er juin 2010 à minuit (heure centrale européenne). -

CAF Africa Cup of Nations Angola 2010

Table of Contents Index Content Page I Final Tournament Participants 2 Schedule 3 Venues 6 CAF Referees 7 Player Statistics 8 Algeria 12 Africa Angola 13 Benin 14 Burkina Faso 15 Cup of Nations Cameroon 16 Egypt 17 Gabon 18 Ghana 19 Angola Ivory Coast 20 Malawi 21 Mali 22 2010 Mozambique 23 Nigeria 24 Togo 25 Tunisia 26 Zambia 27 Match Statistics 28 II Qualifying 32 © by soccer library 2010 CAF Africa Cup of Nations Participants © by soccer library 2 2010 CAF Africa Cup of Nations Group Stage League Tables Fixtures & Results Pos Team Pd W D L GF GA GD Pts Angola 4 : 4 Mali Round 1 1 Angola 3 1 2 0 6 4 2 5 Malawi 3 : 0 Algeria Round 1 2 Algeria 3 1 1 1 1 3 -2 4 Angola 2 : 0 Malawi Round 2 Mali 0 : 1 Algeria Round 2 3 Mali 3 1 1 1 7 6 1 4 Angola 0 : 0 Algeria Round 3 Group A Group A 4 Malawi 3 1 0 2 4 5 -1 3 Mali 3 : 1 Malawi Round 3 Pos Team Pd W D L GF GA GD Pts Ghana : Togo Round 1 1 Ivory Coast 2 1 1 0 3 1 2 4 Ivory Coast 0 : 0 Burkina Faso Round 1 B B 2 Ghana 2 1 0 1 2 3 -1 3 Burkina Faso : Togo Round 2 Ivory Coast 3 : 1 Ghana Round 2 3 Burkina Faso 2 0 1 1 0 1 -1 1 Burkina Faso 0 : 1 Ghana Round 3 Group Group 4 Togo 0 Ivory Coast : Togo Round 3 © by soccer library 3 2010 CAF Africa Cup of Nations Group Stage League Tables Fixtures & Results Pos Team Pd W D L GF GA GD Pts Egypt 3 : 1 Nigeria Round 1 1 Egypt 3 3 0 0 7 1 6 9 Mozambique 2 : 2 Benin Round 1 2 Nigeria 3 2 0 1 5 3 2 6 Egypt 2 : 0 Mozambique Round 2 Nigeria 1 : 0 Benin Round 2 3 Benin 3 0 1 2 2 5 -3 1 Egypt 2 : 0 Benin Round 3 Group C Group C 4 Mozambique 3 0 1 2 2 7 -5 1 -

Sccl 2021 Cf Monterrey

CF QUARTER FINALS COLUMBUS MONTERREY (2) SCCL 2021 (2) CREW MAY 5 | 8 PM ET | BBVA Bancomer FACTS They tied 2-2 in the first leg at Historic Crew Stadium, Columbus, Ohio USA (Apr 28, 2021). Milton Valenzuela and Lucas Zelarayán scored for Columbus Crew, while Ake Loba and Alfonso Alvarado for CF Monterrey. CF MONTERREY 6th participation in the SCCL (2010/11, 2011/12, 2012/13, 2016/17, 2019 and 2021). SCCL record: GP-49 W-34 D-9 L-6 (GF-103 GA-34). Including the late Champions Cup from 1962 (40W-17D-10L). CF Monterrey is the team that has won the Scotiabank Concacaf Champions League the most times since 2008 4 (2010/11, 2011/12, 2012/13 and 2019). They are the only team to win SCCL three consecutive times (2010/11, 2011/12 and 2012/13) under head coach Víctor Manuel Vucetich and is the team that scored the most goals in SCCL finals (12). Undefeated champion twice: 2010/11 and 2012/13. Los Rayados have the best Concacaf Champions League winning percentage (69.4%) and is the team with the most wins in the KO round (19). Head Coach: Javier Aguirre (MEX), 62 years old. With the Mexico National Team, he was champion of the Concacaf Gold Cup in 2009 and directed the 2002 and 2010 FIFA World Cups, the 2001 Copa América and the 2002 and 2009 Gold Cup. He won the 1999 Winter Tournament with Pachuca (MEX) and 3 Cups in the United Arab Emirates (UAE League Cup 2016 and President Cup 2016 and 2017) with Al- Wahda FC (UAE). -

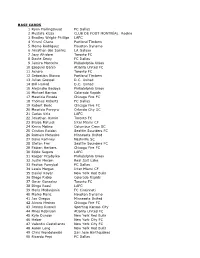

2021 Topps MLS Checklist(1).Xls

BASE CARDS 1 Ryan Hollingshead FC Dallas 2 Mustafa Kizza CLUB DE FOOT MONTRÉAL Rookie 3 Bradley Wright-Phillips LAFC 4 Yimmi Chara Portland Timbers 5 Memo Rodriguez Houston Dynamo 6 Jonathan dos Santos LA Galaxy 7 Jozy Altidore Toronto FC 8 Dante Sealy FC Dallas 9 Jamiro Monteiro Philadelphia Union 10 Ezequiel Barco Atlanta United FC 11 Achara Toronto FC 12 Sebastian Blanco Portland Timbers 13 Julian Gressel D.C. United 14 Bill Hamid D.C. United 15 Alejandro Bedoya Philadelphia Union 16 Michael Barrios Colorado Rapids 17 Mauricio Pineda Chicago Fire FC 18 Thomas Roberts FC Dallas 19 Robert Beric Chicago Fire FC 20 Mauricio Pereyra Orlando City SC 21 Carlos Vela LAFC 22 Jonathan Osorio Toronto FC 23 Blaise Matuidi Inter Miami CF 24 Kevin Molino Columbus Crew SC 25 Cristian Roldan Seattle Sounders FC 26 Romain Metanire Minnesota United 27 Dave Romney Nashville SC 28 Stefan Frei Seattle Sounders FC 29 Fabian Herbers Chicago Fire FC 30 Eddie Segura LAFC 31 Kacper Przybylko Philadelphia Union 32 Justin Meram Real Salt Lake 33 Paxton Pomykal FC Dallas 34 Lewis Morgan Inter Miami CF 35 Daniel Royer New York Red Bulls 36 Diego Rubio Colorado Rapids 37 Omar Gonzalez Toronto FC 38 Diego Rossi LAFC 39 Haris Medunjanin FC Cincinnati 40 Marko Maric Houston Dynamo 41 Jan Gregus Minnesota United 42 Alvaro Medran Chicago Fire FC 43 Johnny Russell Sporting Kansas City 44 Miles Robinson Atlanta United FC 45 Kyle Duncan New York Red Bulls 46 Heber New York City FC 47 Valentin Castellanos New York City FC 48 Aaron Long New York Red Bulls 49 Chris Wondolowski -

DECLARATION I Hereby Declare That This Thesis Is the Result of My Own

DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my own original work and that no part of it has been presented for another degree in this university or elsewhere. Candidate’s Signature:………………….……………………………………………………… Candidate’s Name:…………………………….………………………………………………. Date:……………………………………………………………………………………………….. I hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of the thesis were supervised in accordance with the guidelines on supervision of thesis laid down by Ashesi University College. Supervisor’s Signature:…………………………….………………………………………….. Supervisor’s Name:………………………………...……………………………………………. Date:………………………………………………..………..……………………………………. 1 | P a g e ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere gratitude goes to my supervisor Dr. Stephen Emmanuel Armah for his immense support and guidance throughout this project. If we were in JSS, I would have received countless strokes of the cane along the way as a result of all my countless slips. Your patience is unmatched. Also, I will want to thank my parents Mr. and Mrs. Ayamga for all their prayer, motivation and financial support during this period. I would choose you guys again without thinking twice if I had the opportunity to choose my own parents. I appreciate all the help and support from my colleague and friend Samuel Larmie and his dad Mr. William Larmie, journalists like Benjamin Epton Owusu, Fiifi Anaman and the ever lovely Juliet Bawuah, and Chairman extraordinaire Herbert Mensah for all the time, insights and direction throughout this process. I am forever grateful. I extend my sincere gratitude to staff of SSNIT offices in various parts of Accra and the Brong Ahafo Region for allowing me information I might not have gotten any other way. Also to all the retired footballers, football administrators, journalists, and everyone who contributed to the success of this process, I am more appreciative of your assistance than you may know. -

FIFA Assistant Referee Joe Fletcher Retires Canadian Soccer Association

FLAG & WHI STL E Official Newsletter of the BC Soccer Referees Association • February 2019 FIFA Assistant Referee Joe Fletcher retires Canadian Soccer Association After a storied 25-year career as a respected FIFA and Canada Soccer Assistant Referee, Niagara native Joe Fletcher will no longer be visible on the touchline. Fletcher received his National Badge in 2005 and joined the FIFA List of Assistant Referees in 2007. He was the recipient of the Ray Morgan Memorial Award in 2012 and received the Canada Soccer Inter- national Achievement Award in 2015. Fletcher successfully completed appointments to the 2014 and 2018 FIFA World Cup™, the 2011 and 2013 Concacaf Gold Cups, the 2008 and 2017 Concacaf Champions League Finals, the FIFA U-20 World Cup Canada 2007 and the FIFA U-20 World Cup Colombia 2011, the 2012 Olympic Games, the 2013 FIFA Club World Cup, the 2016 Copa America, the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup, the 2011, 2015 and 2018 Cana- dian Championship Finals, the 2014 and 2016 MLS Cup Finals plus countless professional matches. “Joe Fletcher has been a leading figure amongst Canada Soccer referees for more than a decade, successfully, and flawlessly accepting appointments each time he’s called on every continent,” said Canada Soccer’s Manager, Referees Isaac Raymond. “After 25 years, we’re proud to work with Joe as he transitions into a mentorship role, bringing his thirst for knowledge and drive to developing the next generation of Canadian referees.” Fletcher, for his part, is most proud of his standing amongst the group of men and women who carry the whis- tle.