Modeling and Analyzing CPU Power and Performance: Metrics, Methods, and Abstractions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory Centric Characterization and Analysis of SPEC CPU2017 Suite

Session 11: Performance Analysis and Simulation ICPE ’19, April 7–11, 2019, Mumbai, India Memory Centric Characterization and Analysis of SPEC CPU2017 Suite Sarabjeet Singh Manu Awasthi [email protected] [email protected] Ashoka University Ashoka University ABSTRACT These benchmarks have become the standard for any researcher or In this paper, we provide a comprehensive, memory-centric charac- commercial entity wishing to benchmark their architecture or for terization of the SPEC CPU2017 benchmark suite, using a number of exploring new designs. mechanisms including dynamic binary instrumentation, measure- The latest offering of SPEC CPU suite, SPEC CPU2017, was re- ments on native hardware using hardware performance counters leased in June 2017 [8]. SPEC CPU2017 retains a number of bench- and operating system based tools. marks from previous iterations but has also added many new ones We present a number of results including working set sizes, mem- to reflect the changing nature of applications. Some recent stud- ory capacity consumption and memory bandwidth utilization of ies [21, 24] have already started characterizing the behavior of various workloads. Our experiments reveal that, on the x86_64 ISA, SPEC CPU2017 applications, looking for potential optimizations to SPEC CPU2017 workloads execute a significant number of mem- system architectures. ory related instructions, with approximately 50% of all dynamic In recent years the memory hierarchy, from the caches, all the instructions requiring memory accesses. We also show that there is way to main memory, has become a first class citizen of computer a large variation in the memory footprint and bandwidth utilization system design. -

Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks

9 Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks Kaivalya M. Dixit IBM Corporation “The reputation of current benchmarketing claims regarding system performance is on par with the promises made by politicians during elections.” Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation (SPEC) was founded in October, 1988, by Apollo, Hewlett-Packard,MIPS Computer Systems and SUN Microsystems in cooperation with E. E. Times. SPEC is a nonprofit consortium of 22 major computer vendors whose common goals are “to provide the industry with a realistic yardstick to measure the performance of advanced computer systems” and to educate consumers about the performance of vendors’ products. SPEC creates, maintains, distributes, and endorses a standardized set of application-oriented programs to be used as benchmarks. 489 490 CHAPTER 9 Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks 9.1 Historical Perspective Traditional benchmarks have failed to characterize the system performance of modern computer systems. Some of those benchmarks measure component-level performance, and some of the measurements are routinely published as system performance. Historically, vendors have characterized the performances of their systems in a variety of confusing metrics. In part, the confusion is due to a lack of credible performance information, agreement, and leadership among competing vendors. Many vendors characterize system performance in millions of instructions per second (MIPS) and millions of floating-point operations per second (MFLOPS). All instructions, however, are not equal. Since CISC machine instructions usually accomplish a lot more than those of RISC machines, comparing the instructions of a CISC machine and a RISC machine is similar to comparing Latin and Greek. 9.1.1 Simple CPU Benchmarks Truth in benchmarking is an oxymoron because vendors use benchmarks for marketing purposes. -

3 — Arithmetic for Computers 2 MIPS Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) Zero Ovf

Chapter 3 Arithmetic for Computers 1 § 3.1Introduction Arithmetic for Computers Operations on integers Addition and subtraction Multiplication and division Dealing with overflow Floating-point real numbers Representation and operations Rechnerstrukturen 182.092 3 — Arithmetic for Computers 2 MIPS Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) zero ovf 1 Must support the Arithmetic/Logic 1 operations of the ISA A 32 add, addi, addiu, addu ALU result sub, subu 32 mult, multu, div, divu B 32 sqrt 4 and, andi, nor, or, ori, xor, xori m (operation) beq, bne, slt, slti, sltiu, sltu With special handling for sign extend – addi, addiu, slti, sltiu zero extend – andi, ori, xori overflow detection – add, addi, sub Rechnerstrukturen 182.092 3 — Arithmetic for Computers 3 (Simplyfied) 1-bit MIPS ALU AND, OR, ADD, SLT Rechnerstrukturen 182.092 3 — Arithmetic for Computers 4 Final 32-bit ALU Rechnerstrukturen 182.092 3 — Arithmetic for Computers 5 Performance issues Critical path of n-bit ripple-carry adder is n*CP CarryIn0 A0 1-bit result0 ALU B0 CarryOut0 CarryIn1 A1 1-bit result1 B ALU 1 CarryOut 1 CarryIn2 A2 1-bit result2 ALU B2 CarryOut CarryIn 2 3 A3 1-bit result3 ALU B3 CarryOut3 Design trick – throw hardware at it (Carry Lookahead) Rechnerstrukturen 182.092 3 — Arithmetic for Computers 6 Carry Lookahead Logic (4 bit adder) LS 283 Rechnerstrukturen 182.092 3 — Arithmetic for Computers 7 § 3.2 Addition and Subtraction 3.2 Integer Addition Example: 7 + 6 Overflow if result out of range Adding +ve and –ve operands, no overflow Adding two +ve operands -

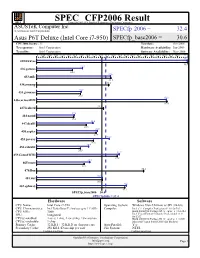

Asustek Computer Inc.: Asus P6T

SPEC CFP2006 Result spec Copyright 2006-2014 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation ASUSTeK Computer Inc. (Test Sponsor: Intel Corporation) SPECfp 2006 = 32.4 Asus P6T Deluxe (Intel Core i7-950) SPECfp_base2006 = 30.6 CPU2006 license: 13 Test date: Oct-2008 Test sponsor: Intel Corporation Hardware Availability: Jun-2009 Tested by: Intel Corporation Software Availability: Nov-2008 0 3.00 6.00 9.00 12.0 15.0 18.0 21.0 24.0 27.0 30.0 33.0 36.0 39.0 42.0 45.0 48.0 51.0 54.0 57.0 60.0 63.0 66.0 71.0 70.7 410.bwaves 70.8 21.5 416.gamess 16.8 34.6 433.milc 34.8 434.zeusmp 33.8 20.9 435.gromacs 20.6 60.8 436.cactusADM 61.0 437.leslie3d 31.3 17.6 444.namd 17.4 26.4 447.dealII 23.3 28.5 450.soplex 27.9 34.0 453.povray 26.6 24.4 454.calculix 20.5 38.7 459.GemsFDTD 37.8 24.9 465.tonto 22.3 470.lbm 50.2 30.9 481.wrf 30.9 42.1 482.sphinx3 41.3 SPECfp_base2006 = 30.6 SPECfp2006 = 32.4 Hardware Software CPU Name: Intel Core i7-950 Operating System: Windows Vista Ultimate w/ SP1 (64-bit) CPU Characteristics: Intel Turbo Boost Technology up to 3.33 GHz Compiler: Intel C++ Compiler Professional 11.0 for IA32 CPU MHz: 3066 Build 20080930 Package ID: w_cproc_p_11.0.054 Intel Visual Fortran Compiler Professional 11.0 FPU: Integrated for IA32 CPU(s) enabled: 4 cores, 1 chip, 4 cores/chip, 2 threads/core Build 20080930 Package ID: w_cprof_p_11.0.054 CPU(s) orderable: 1 chip Microsoft Visual Studio 2008 (for libraries) Primary Cache: 32 KB I + 32 KB D on chip per core Auto Parallel: Yes Secondary Cache: 256 KB I+D on chip per core File System: NTFS Continued on next page Continued on next page Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation [email protected] Page 1 http://www.spec.org/ SPEC CFP2006 Result spec Copyright 2006-2014 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation ASUSTeK Computer Inc. -

Continuous Profiling: Where Have All the Cycles Gone?

Continuous Profiling: Where Have All the Cycles Gone? JENNIFER M. ANDERSON, LANCE M. BERC, JEFFREY DEAN, SANJAY GHEMAWAT, MONIKA R. HENZINGER, SHUN-TAK A. LEUNG, RICHARD L. SITES, MARK T. VANDEVOORDE, CARL A. WALDSPURGER, and WILLIAM E. WEIHL Digital Equipment Corporation This article describes the Digital Continuous Profiling Infrastructure, a sampling-based profiling system designed to run continuously on production systems. The system supports multiprocessors, works on unmodified executables, and collects profiles for entire systems, including user programs, shared libraries, and the operating system kernel. Samples are collected at a high rate (over 5200 samples/sec. per 333MHz processor), yet with low overhead (1–3% slowdown for most workloads). Analysis tools supplied with the profiling system use the sample data to produce a precise and accurate accounting, down to the level of pipeline stalls incurred by individual instructions, of where time is being spent. When instructions incur stalls, the tools identify possible reasons, such as cache misses, branch mispredictions, and functional unit contention. The fine-grained instruction-level analysis guides users and automated optimizers to the causes of performance problems and provides important insights for fixing them. Categories and Subject Descriptors: C.4 [Computer Systems Organization]: Performance of Systems; D.2.2 [Software Engineering]: Tools and Techniques—profiling tools; D.2.6 [Pro- gramming Languages]: Programming Environments—performance monitoring; D.4 [Oper- ating Systems]: General; D.4.7 [Operating Systems]: Organization and Design; D.4.8 [Operating Systems]: Performance General Terms: Performance Additional Key Words and Phrases: Profiling, performance understanding, program analysis, performance-monitoring hardware An earlier version of this article appeared at the 16th ACM Symposium on Operating System Principles (SOSP), St. -

Specfp Benchmark Disclosure

SPEC CFP2006 Result Copyright 2006-2016 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation Cisco Systems SPECfp2006 = Not Run Cisco UCS C220 M4 (Intel Xeon E5-2667 v4, 3.20 GHz) SPECfp_base2006 = 125 CPU2006 license: 9019 Test date: Mar-2016 Test sponsor: Cisco Systems Hardware Availability: Mar-2016 Tested by: Cisco Systems Software Availability: Dec-2015 0 30.0 60.0 90.0 120 150 180 210 240 270 300 330 360 390 420 450 480 510 540 570 600 630 660 690 720 750 780 810 840 900 410.bwaves 572 416.gamess 43.1 433.milc 72.5 434.zeusmp 225 435.gromacs 63.4 436.cactusADM 894 437.leslie3d 427 444.namd 31.6 447.dealII 67.6 450.soplex 48.3 453.povray 62.2 454.calculix 61.6 459.GemsFDTD 242 465.tonto 52.1 470.lbm 799 481.wrf 120 482.sphinx3 91.6 SPECfp_base2006 = 125 Hardware Software CPU Name: Intel Xeon E5-2667 v4 Operating System: SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 12 SP1 (x86_64) CPU Characteristics: Intel Turbo Boost Technology up to 3.60 GHz 3.12.49-11-default CPU MHz: 3200 Compiler: C/C++: Version 16.0.0.101 of Intel C++ Studio XE for Linux; FPU: Integrated Fortran: Version 16.0.0.101 of Intel Fortran CPU(s) enabled: 16 cores, 2 chips, 8 cores/chip Studio XE for Linux CPU(s) orderable: 1,2 chips Auto Parallel: Yes Primary Cache: 32 KB I + 32 KB D on chip per core File System: xfs Secondary Cache: 256 MB I+D on chip per core System State: Run level 3 (multi-user) Continued on next page Continued on next page Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation [email protected] Page 1 http://www.spec.org/ SPEC CFP2006 Result Copyright 2006-2016 Standard Performance -

Intel Corporation: Lenovo T400 (Intel Core 2 Duo T9900)

SPEC CFP2006 Result spec Copyright 2006-2014 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation Intel Corporation SPECfp2006 = 21.2 Lenovo T400 (Intel Core 2 Duo T9900) SPECfp_base2006 = 20.5 CPU2006 license: 13 Test date: Mar-2009 Test sponsor: Intel Corporation Hardware Availability: Mar-2009 Tested by: Intel Corporation Software Availability: Nov-2008 0 1.00 3.00 5.00 7.00 9.00 11.0 13.0 15.0 17.0 19.0 21.0 23.0 25.0 27.0 29.0 32.0 27.6 410.bwaves 27.6 19.9 416.gamess 19.1 18.8 433.milc 18.8 434.zeusmp 24.1 19.7 435.gromacs 19.3 30.7 436.cactusADM 30.0 437.leslie3d 17.5 16.2 444.namd 16.2 24.5 447.dealII 22.1 17.1 450.soplex 16.9 30.4 453.povray 24.3 20.0 454.calculix 20.0 16.3 459.GemsFDTD 16.5 19.2 465.tonto 17.5 470.lbm 15.3 21.2 481.wrf 21.2 30.8 482.sphinx3 31.0 SPECfp_base2006 = 20.5 SPECfp2006 = 21.2 Hardware Software CPU Name: Intel Core 2 Duo T9900 Operating System: Windows XP Professional w/ SP2 (64-bit) CPU Characteristics: Compiler: Intel C++ Compiler Professional 11.0 for IA32 CPU MHz: 3066 Build 20080930 Package ID: w_cproc_p_11.0.054 Intel Visual Fortran Compiler Professional 11.0 FPU: Integrated for IA32 CPU(s) enabled: 2 cores, 1 chip, 2 cores/chip Build 20080930 Package ID: w_cprof_p_11.0.054 CPU(s) orderable: 1 chip Microsoft Visual Studio 2008 (for libraries) Primary Cache: 32 KB I + 32 KB D on chip per core Auto Parallel: Yes Secondary Cache: 6 MB I+D on chip per chip File System: NTFS Continued on next page Continued on next page Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation [email protected] Page 1 http://www.spec.org/ -

Historical Perspective and Further Reading 4.7

4.7 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 4.7 From the earliest days of computing, designers have specified performance goals—ENIAC was to be 1000 times faster than the Harvard Mark-I, and the IBM Stretch (7030) was to be 100 times faster than the fastest computer then in exist- ence. What wasn’t clear, though, was how this performance was to be measured. The original measure of performance was the time required to perform an individual operation, such as addition. Since most instructions took the same exe- cution time, the timing of one was the same as the others. As the execution times of instructions in a computer became more diverse, however, the time required for one operation was no longer useful for comparisons. To take these differences into account, an instruction mix was calculated by mea- suring the relative frequency of instructions in a computer across many programs. Multiplying the time for each instruction by its weight in the mix gave the user the average instruction execution time. (If measured in clock cycles, average instruction execution time is the same as average CPI.) Since instruction sets were similar, this was a more precise comparison than add times. From average instruction execution time, then, it was only a small step to MIPS. MIPS had the virtue of being easy to understand; hence it grew in popularity. The In More Depth section on this CD dis- cusses other definitions of MIPS, as well as its relatives MOPS and FLOPS! The Quest for an Average Program As processors were becoming more sophisticated and relied on memory hierar- chies (the topic of Chapter 7) and pipelining (the topic of Chapter 6), a single exe- cution time for each instruction no longer existed; neither execution time nor MIPS, therefore, could be calculated from the instruction mix and the manual. -

An Evaluation of the TRIPS Computer System

Appears in the Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Architecture Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems An Evaluation of the TRIPS Computer System Mark Gebhart Bertrand A. Maher Katherine E. Coons Jeff Diamond Paul Gratz Mario Marino Nitya Ranganathan Behnam Robatmili Aaron Smith James Burrill Stephen W. Keckler Doug Burger Kathryn S. McKinley Department of Computer Sciences The University of Texas at Austin [email protected] www.cs.utexas.edu/users/cart Abstract issue-width scaling of conventional superscalar architec- The TRIPS system employs a new instruction set architec- tures. Because of these trends, major microprocessor ven- ture (ISA) called Explicit Data Graph Execution (EDGE) dors have abandoned architectures for single-thread perfor- that renegotiates the boundary between hardware and soft- mance and turned to the promise of multiple cores per chip. ware to expose and exploit concurrency. EDGE ISAs use a While many applications can exploit multicore systems, this block-atomic execution model in which blocks are composed approach places substantial burdens on programmers to par- of dataflow instructions. The goal of the TRIPS design is allelize their codes. Despite these trends, Amdahl’s law dic- to mine concurrency for high performance while tolerating tates that single-thread performance will remain key to the emerging technology scaling challenges, such as increas- future success of computer systems [9]. ing wire delays and power consumption. This paper eval- In response to semiconductor scaling trends, we designed uates how well TRIPS meets this goal through a detailed a new architecture and microarchitecture intended to extend ISA and performance analysis. -

Dell Inc.: Poweredge T610 (Intel Xeon X5690, 3.46 Ghz)

SPEC CFP2006 Result spec Copyright 2006-2014 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation Dell Inc. SPECfp2006 = 64.6 PowerEdge T610 (Intel Xeon X5690, 3.46 GHz) SPECfp_base2006 = 60.3 CPU2006 license: 55 Test date: Jun-2011 Test sponsor: Dell Inc. Hardware Availability: Feb-2011 Tested by: Dell Inc. Software Availability: Apr-2011 0 10.0 25.0 40.0 55.0 70.0 85.0 100 110 120 130 140 150 160 170 180 190 200 210 220 230 240 250 260 270 280 290 305 410.bwaves 180 31.0 416.gamess 26.2 57.4 433.milc 57.1 434.zeusmp 121 26.0 435.gromacs 24.5 436.cactusADM 301 437.leslie3d 104 22.2 444.namd 21.7 447.dealII 44.8 450.soplex 35.5 43.7 453.povray 34.7 37.1 454.calculix 32.9 91.8 459.GemsFDTD 77.6 37.1 465.tonto 27.7 470.lbm 293 481.wrf 51.2 64.8 482.sphinx3 58.5 SPECfp_base2006 = 60.3 SPECfp2006 = 64.6 Hardware Software CPU Name: Intel Xeon X5690 Operating System: SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 SP1 (x86_64), CPU Characteristics: Intel Turbo Boost Technology up to 3.73 GHz Kernel 2.6.32.12-0.7-default CPU MHz: 3467 Compiler: Intel C++ and Fortran Intel 64 Compiler XE for FPU: Integrated applications running on Intel 64 Version 12.0 Update 3 CPU(s) enabled: 12 cores, 2 chips, 6 cores/chip Auto Parallel: Yes CPU(s) orderable: 1,2 chips File System: ext3 Primary Cache: 32 KB I + 32 KB D on chip per core System State: Run level 3 (multi-user) Secondary Cache: 256 KB I+D on chip per core Base Pointers: 64-bit Continued on next page Continued on next page Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation [email protected] Page 1 http://www.spec.org/ SPEC CFP2006 Result spec Copyright 2006-2014 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation Dell Inc. -

A Lightweight Processor Benchmark Mark Claypool Worcester Polytechnic Institute, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@WPI Worcester Polytechnic Institute DigitalCommons@WPI Computer Science Faculty Publications Department of Computer Science 7-1-1998 Touchstone - A Lightweight Processor Benchmark Mark Claypool Worcester Polytechnic Institute, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/computerscience-pubs Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Suggested Citation Claypool, Mark (1998). Touchstone - A Lightweight Processor Benchmark. Retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/computerscience-pubs/206 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Computer Science at DigitalCommons@WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Computer Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WPI. WPI-CS-TR-98-16 July 1998 Touchstone { A Lightweight Pro cessor Benchmark by Mark Claypool Computer Science Technical Rep ort Series WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE Computer Science Department 100 Institute Road, Worcester, Massachusetts 01609-2280 Touchstone { A Lightweight Pro cessor Benchmark Mark Claypool [email protected] Worcester Polytechnic Institute Computer Science Department August 11, 1998 Abstract Benchmarks are valuable for comparing pro cessor p erformance. However, p orting and run- ning pro cessor b enchmarks on new platforms can b e dicult. Touchstone, a simple addition b enchmark, is designed to overcome p ortability problems, while retaining p erformance measure- ment accuracy. In this pap er, we present exp erimental results that showTouchstone correlates strongly with pro cessor p erformance under other b enchmarks. Equally imp ortant, we presenta measure of p ortability that demonstrates Touchstone is easier to p ort and run than other b ench- marks. -

Chapter 3: Arithmetic for Computers

182.092 Computer Architecture Chapter 3: Arithmetic for Computers Adapted from Computer Organization and Design, 4th Edition, Patterson & Hennessy, © 2008, Morgan Kaufmann Publishers and Mary Jane Irwin (www.cse.psu.edu/research/mdl/mji) 182.092 Chapter 3.1 Herbert Grünbacher, TU Vienna, 2010 Review: MIPS (RISC) Design Principles Simplicity favors regularity fixed size instructions small number of instruction formats opcode always the first 6 bits Smaller is faster limited instruction set limited number of registers in register file limited number of addressing modes Make the common case fast arithmetic operands from the register file (load-store machine) allow instructions to contain immediate operands Good design demands good compromises three instruction formats (R, I, J) 182.092 Chapter 3.2 Herbert Grünbacher, TU Vienna, 2010 Review: MIPS Addressing Modes Illustrated 1. Register addressing op rs rt rd funct Register word operand 2. Base (displacement) addressing op rs rt offset Memory word or byte operand base register 3. Immediate addressing op rs rt operand 4. PC-relative addressing op rs rt offset Memory branch destination instruction Program Counter (PC) 5. Pseudo-direct addressing op jump address Memory || jump destination instruction Program Counter (PC) 182.092 Chapter 3.3 Herbert Grünbacher, TU Vienna, 2010 Number Representations 32-bit signed numbers (2’s complement): 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000two = 0ten maxint 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0001two = + 1ten ... 0111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1110two = + 2,147,483,646ten 0111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111two = + 2,147,483,647ten 1000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000two = – 2,147,483,648ten 1000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0001two = – 2,147,483,647ten ..