The Taxation Savings in Australia Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAX REFORM and SMALL BUSINESS Eric J

REFERENCES TAX REFORM AND SMALL BUSINESS Eric J. Toder * Institute Fellow, Urban Institute and Co-Director, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center House Committee on Small Business April 15, 2015 Chairman Chabot, Ranking Member Velazquez, and Members of the Committee. Thank you for inviting me to appear today to discuss the effects of tax reform on small business. There is a growing consensus that the current system of taxing business income needs reform and bi-partisan agreement on some of the main directions of reform, although not the details. The main drivers for reform are concerns with a corporate tax system that discourages investment in the United States, encourages US multinational corporations to retain profits overseas, and places some US-based multinationals at a competitive disadvantage with foreign- based companies, while at the same time raising relatively little revenue, providing selected preferences to favored assets and industries, and allowing some US multinationals to pay very low tax rates by shifting reported profits to low tax countries. • The United States has the highest corporate tax rate in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). This discourages investment in the United States by both US and foreign-based multinational corporations and encourages corporations to report income in other jurisdictions. • The US rules for taxing multinational corporations encourage US firms to earn and retain profits overseas and place some companies at a competitive disadvantage, encouraging *The views expressed are my own and should not be attributed to the Tax Policy Center or the Urban Institute, its board, or its funders. I thank Leonard Burman, Donald Marron, and George Plesko for helpful comments and Joseph Rosenberg, and John Wieselthier for assistance with the Tax Policy Center simulations. -

Should EU Implement Its Present Proposal of a Financial Transaction Tax?

Should EU implement its present proposal of a financial transaction tax? Authors: Fredrik Hansson (890429-4033) Tutor: Thomas Ericson Degree of Bachelor of Science in Examiner: Dominique Anxo Business Administration and Subject: Economics Economics Level and semester: Bachelor´s Thesis, Spr 2012 Abstract: This paper study the possibility of implementing a financial transaction tax within the European Union, as a possibility to discourage future financial bubbles and force more fundamental values within the financial market. It is found, after reviewing current research; covering volatility, market volume and speculation, and empirical evidence, that a financial transaction tax fulfill the purpose of creating a more efficient financial system in the case of European Union. Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Theoretical framework .......................................................................................................................... 3 Empirical studies ................................................................................................................................ 10 United Kingdom ............................................................................................................................. 10 Sweden ........................................................................................................................................... 11 Hong Kong, Japan, -

Ecotaxes: a Comparative Study of India and China

Ecotaxes: A Comparative Study of India and China Rajat Verma ISBN 978-81-7791-209-8 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. ECOTAXES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INDIA AND CHINA1 Rajat Verma2 Abstract This paper attempts to compare various forms of ecotaxes adopted by India and China in order to reduce their carbon emissions by 2020 and to address other environmental issues. The study contributes to the literature by giving a comprehensive definition of ecotaxes and using it to analyse the status of these taxes in India and China. -

Personal Income Tax Changes | Policy Bulletin

POLICY BULLETIN PERSONAL INCOME TAX CHANGES 10 July 2019 IN BRIEF • Changes to income tax offsets and rates have received Royal Assent • The low and middle income tax offset (LMITO) changes apply to the 2018-19 year • The LMITO applies in a phased manner and is non-refundable • Changes to personal income tax rates apply from the 2022-23 year SUMMARY OF CHANGES The Treasury Laws Amendment (Tax Relief So Working Australians Keep More of Their Money) Act 2019 received Royal Assent on 5 July 2019. The Act: • increases the base and maximum amounts of the low and middle income tax offset (LMITO) to $255 and $1080, respectively, for the 2018-19, 2019-20, 2020-21 and 2021-22 financial years • increases the maximum amount of the low income tax offset from $645 to $700 from the 2022-23 financial year • reduces the tax payable by individuals from the 2022-23 financial year by increasing the top threshold of the 19 per cent income tax bracket from $41,000 to $45,000 • reduces the 32.5 per cent income tax rate to 30 per cent from the 2024-25 financial year. 1 LOW AND MIDDLE INCOME TAX OFFSET From the 2018-19 income year to the 2021-22 financial year, the LMITO for Australian resident taxpayers increases from a maximum amount of $530 to $1080 per annum and the base amount increases from $200 to $255 per annum. The LMITO will directly reduce the amount of tax payable but does not reduce the Medicare levy. As a non- refundable offset, any unused low and middle income tax offset cannot be refunded. -

Leveraging the New Flat 21% Tax Bracket for C-Corporations

Leveraging the New Flat 21% Tax Bracket for C-Corporations Tax rates for C-Corporations are at an all-time low. Since the tax tide frequently changes, now might be a good opportunity to take advantage of these lower tax rates before they go back up. Previously, C-Corporations were taxed at up to 39% (federal). Some C-Corporations may have moved this higher taxed income into lower individual tax brackets by increasing the owners’ salaries, paying bonuses and paying higher rent on personally owned business real estate. Now, the C-Corporation is in a 21% bracket no matter how much income it generates. The employee/shareholders, however, could be in a personal federal tax bracket as high as 40.8%. A bonus could lead to higher overall tax. Cross-Purchase Funding Life insurance funding for a cross-purchase buy-sell agreement has traditionally been done with bonuses paid to the shareholders. This may no longer be advised. In addition to higher individual tax rates, the bonus may be subject to FICA and other employment taxes that both the business and employee must pay. Consider a dividend instead of the bonus. While a dividend is not tax deductible to the business, the shareholder is taxed at between 0% and 20% (depending on other income), rather than at his or her marginal tax rate. Additionally, there are no FICA or other payroll taxes on dividends. The dividend’s “double taxation” (once at the corporate level and again at the shareholder level) maybe less than the taxation of a bonus. Accumulated Earning Tax Businesses have tended to accumulate earnings inside the company in an effort to avoid the double taxation of a dividend to the shareholders. -

Individual Income Tax: Arin / Istock © Sk the Basics and New Changes

PAGE ONE Economics® Individual Income Tax: arin / iStock © sk The Basics and New Changes Jeannette N. Bennett, Senior Economic Education Specialist GLOSSARY “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Adjusted gross income: Gross income minus —Ben Franklin specific adjustments to income. (Gross income is the total amount earned before any adjustments are subtracted.) Earned income: Money you get for the work Introduction you do. There are two ways to get earned income: You work for someone who pays Taxes are certain. One primary tax is the individual income tax. Congress you, or you own or run a business or farm. initiated the first federal income tax in 1862 to collect revenue for the Income: The payment people receive for pro- expenses of the Civil War. The tax was eliminated in 1872. It made a short- viding resources in the marketplace. When lived comeback in 1894 but was ruled unconstitutional the very next year. people work, they provide human resources (labor) and in exchange they receive income Then, in 1913, the federal income tax resurfaced when the 16th Amend- in the form of wages or salaries. People also ment to the Constitution gave Congress legal authority to tax income. earn income in the form of rent, profit, and And today, the federal income tax is well established and certain. interest. Income tax: Taxes on income, both earned (salaries, wages, tips, commissions) and 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (1913) unearned (interest, dividends). Income taxes can be levied on both individuals The Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever (personal income taxes) and businesses source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard (business and corporate income taxes). -

How Do Federal Income Tax Rates Work? XXXX

TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System INDIVIDUAL INCOME TAX How do federal income tax rates work? XXXX Q. How do federal income tax rates work? A. The federal individual income tax has seven tax rates that rise with income. Each rate applies only to income in a specific range (tax bracket). CURRENT INCOME TAX RATES AND BRACKETS The federal individual income tax has seven tax rates ranging from 10 percent to 37 percent (table 1). The rates apply to taxable income—adjusted gross income minus either the standard deduction or allowable itemized deductions. Income up to the standard deduction (or itemized deductions) is thus taxed at a zero rate. Federal income tax rates are progressive: As taxable income increases, it is taxed at higher rates. Different tax rates are levied on income in different ranges (or brackets) depending on the taxpayer’s filing status. In TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System INDIVIDUAL INCOME TAX How do federal income tax rates work? XXXX 2020 the top tax rate (37 percent) applies to taxable income over $518,400 for single filers and over $622,050 for married couples filing jointly. Additional tax schedules and rates apply to taxpayers who file as heads of household and to married individuals filing separate returns. A separate schedule of tax rates applies to capital gains and dividends. Tax brackets are adjusted annually for inflation. BASICS OF PROGRESSIVE INCOME TAXATION Each tax rate applies only to income in a specific tax bracket. Thus, if a taxpayer earns enough to reach a new bracket with a higher tax rate, his or her total income is not taxed at that rate, just the income in that bracket. -

401(K) Tax Policy Creates Inequality

FEB 15 401(K) TAX POLICY CREATES tax revenue5 from 2014-2018 (not including state deductions) – compound over time so that current federal tax policy for retirement INEQUALITY account contributions benefits fewer and fewer people. With some irony, the described inequality is a result of the by Teresa Ghilarducci, Bernard L. and Irene Schwartz Chair in Eco- progressive nature of the federal income tax system, where higher 6 nomic Policy Analysis at The New School, and Adam Hayes, Research incomes are subject to higher marginal tax rates. Congress Assistant with the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis (starting in 1912 and accelerating the deductions in 1978 with the (SCEPA) at The New School establishment of the 401(k) plan) aimed to encourage retirement savings by allowing qualified retirement plan contributions to be deducted from adjusted gross income (AGI) and deferred until INTRODUCTION retirement, when income tax brackets are presumed to be lower for workers. The federally-funded tax deduction for retirement savings Though well-intentioned, the current system of tax deferral turns out to be asymmetric, benefiting higher income earners (those for retirement contributions undermines public policy aimed at in the highest tax bracket) the most. strengthening retirement security for all Americans. In fact, it has The unevenness of income taxation on retirement accounts takes become a regressive policy that contributes to wealth inequality. Two effect both directly and indirectly. First, the high-income earner employees who are identical savers and investors in every way except enjoys a larger tax deduction in the current period since they are for income, receive different rates of return due only to the effects of using a higher tax rate to compute the deduction. -

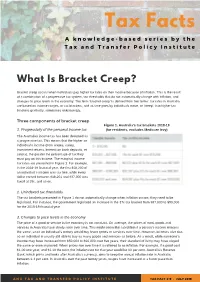

What Is Bracket Creep?

Tax Facts A k n o w l e d g e - b a s e d s e r i e s b y t h e T a x a n d T r a n s f e r P o l i c y I n s t i t u t e What Is Bracket Creep? Bracket creep occurs when individuals pay higher tax rates on their income because of inflation. This is the result of a combination of a progressive tax system, tax thresholds that do not automatically change with inflation, and changes to price levels in the economy. The term ‘bracket creep’ is derived from two terms: tax rates in Australia are based on income ranges, or tax brackets, and as time goes by individuals move, or ‘creep’, into higher tax brackets gradually, sometimes unknowingly. Three components of bracket creep Figure 1. Australia's tax brackets 2018-19 1. Progressivity of the personal income tax (for residents, excludes Medicare levy) The Australian income tax has been designed as a progressive tax. This means that the higher an individual’s income (from wages, salary, investment returns, interest on bank deposits, et cetera), the greater the percentage of tax they must pay on this income. The marginal income tax rates are presented in Figure 1. For example, in the 2018-19 financial year, the first $18,200 of an individual’s income was tax free, while every dollar earned between $18,201 and $37,000 was taxed at 19c, and so on. 2. Unindexed tax thresholds The tax brackets presented in Figure 1 do not automatically change when inflation occurs; they need to be legislated. -

A Bit Rich: a Government Plan to Make Tax Less

A bit rich: A Government plan to make tax less progressive The Government’s tax plan will make income tax less progressive, with most of the benefit going to those on high incomes. The tax plan will see the proportion of tax paid by high income earners fall and the proportion of tax paid by low and middle income earners rise. Matt Grudnoff April 2019 If the Government’s tax plan is introduced it will reduce the progressive nature of the income tax system and will mean that high income earners will pay a smaller proportion of tax than they do now. It will also mean that low and middle income earners will pay a higher proportion of tax. Figure 1 – Change in proportion of tax paid by high, middle and low income earners Low income Middle income High income 3.0% 2.2% 25 1.7% - 2.0% 1.0% 0.0% 19 and 2024 - -1.0% -2.0% -3.0% -4.0% paid paid between 2018 Change in proportion of income tax tax income of proportion in Change -4.0% -5.0% Source: ATO (2019) Individual Detailed Table 16: Percentile distribution of taxable individuals, Australian Taxation Office, available at <https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Research-and- statistics/In-detail/Taxation-statistics/Taxation-statistics-2016- 17/?anchor=Individualsdetailedtables#Individualsdetailedtables> and Australia Institute Modelling (see Appendix 2) A bit rich: A Government plan to make tax less progressive 1 The Government’s income tax plan in the 2019-20 budget extends its tax plan from the 2018 budget. -

An Analysis of Senator Bernie Sanders's Tax Proposals

PRELIMINARY DRAFT – EMBARGOED UNTIL 1PM, 3/4/16 AN ANALYSIS OF SENATOR BERNIE SANDERS’S TAX PROPOSALS Frank Sammartino, Len Burman, Jim Nunns, Joseph Rosenberg, and Jeff Rohaly March 4, 2016 ABSTRACT Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders proposes significant increases in federal income, payroll, business, and estate taxes, and new excise taxes on financial transactions and carbon. New revenues would pay for universal health care, education, family leave, rebuilding the nation’s infrastructure, and more. TPC estimates the tax proposals would raise $15.3 trillion over the next decade. All income groups would pay some additional tax, but most would come from high-income households, particularly those with the very highest income. His proposals would raise taxes on work, saving, and investment, in some cases to rates well beyond recent historical experience in the US. We are grateful to Donald Marron, Pamela Olson, Eric Toder, and Roberton Williams for helpful comments on earlier drafts. Lydia Austin and Blake Greene prepared the draft for publication. The authors are solely responsible for any errors. The views expressed do not reflect the views of the Sanders campaign or of those who kindly reviewed drafts. The Tax Policy Center is nonpartisan. Nothing in this report should be construed as an endorsement of or opposition to any campaign or candidate. For information about the Tax Policy Center’s approach to analyzing candidates’ tax plans, please see http://election2016.taxpolicycenter.org/engagement-policy/. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Tax Policy Center or its funders. -

PFP Tax Bracket Management Chart

Robert S. Keebler, CPA/PFS, MST, AEP: Bracket Management 15 Impactful Bracket Management Ideas “Flying Below the Radar” Bracket Management Checklist 1. Traditional IRA/401k Contributions: Contribute to Traditional IRAs/401ks in high income years to reduce current income tax on wages and reduce $622,050 investment taxation during accumulation years. Determine the client’s current tax bracket. 2. Roth IRA/401k Contributions: Contribute to Roth IRAs/401ks in low income 37% Ordinary $326,600-$426,600 years to reduce taxation during retirement years and reduce investment Income Tax Rate $250,000 Project the client’s future tax brackets. taxation during accumulation years. § 199A Limits 3. Roth IRA/401k Conversions: Make Roth Conversions to the extent the current 3.8% NIIT marginal rate is less than or equal to the projected average rate on distributions Determine if and when the NIIT, AMT, § 199A Limits, and higher brackets will apply. during retirement. Thresholds for married filing jointly. 4. Timing of Deductions: Shift deductions to years in which provide the greatest tax benefit – note due to the phase-out of itemized deductions and the AMT this 2020 Federal Income Tax Brackets Use the projections to build the client’s portfolio according might not always be the year with the greatest income. to the Tax Rate Asset Allocation chart. 5. Capital Loss Harvesting: Harvest losses in high income years to offset capital gains. Build the portfolio with an understanding of the Taxation 6. Capital Gain Harvesting: Harvest gains in low income years to fill up the 0% bracket and evaluate gain harvesting which incurs taxation at lower rate in of Retirement Distributions.