Downloaded From: Version: Accepted Version Publisher: Manchester University Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

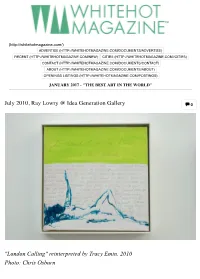

July 2010, Ray Lowry @ Idea Generation Gallery 0

(http://whitehotmagazine.com/) ADVERTISE (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/DOCUMENTS/ADVERTISE) RECENT (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/NEW) CITIES (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM//CITIES) CONTACT (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/DOCUMENTS/CONTACT) ABOUT (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/DOCUMENTS/ABOUT) OPENINGS LISTINGS (HTTP://WHITEHOTMAGAZINE.COM/POSTINGS) JANUARY 2017 - "THE BEST ART IN THE WORLD" July 2010, Ray Lowry @ Idea Generation Gallery 0 "London Calling" reinterpreted by Tracy Emin, 2010 Photo: Chris Osburn Ray Lowry: London Calling Idea Generation Gallery (http://www.ideageneration.co.uk/generationgallery.php) 11 Chance Street London, E2 7JB June 18th through July 4th, 2010 Ray Lowry: London Calling at the Idea Generation Gallery in East London pays tribute to Ray Lowry's iconic cover art for The Clash's 1979 album, London Calling. For the show, thirty prominent artists contributed their interpretations of Lowry's seminal album cover. In addition to the artists' takes on Lowry's cover, they were invited to have a look at how he and his ideologies had influenced them. Alongside these works, original sketches, designs for the album cover as well as private sketchbooks, personal letters, previously unseen photographs and painting are on show. Originally from Manchester, Ray Lowry started his career as an artist drawing for Punch Magazine, International Times and Private Eye. His association with the music press began in the 70s, most notably with NME for which he created a variety of cartoons and illustrations. He met The Clash at Manchester's Electric Circus where they were the supporting act for the Sex Pistols during raucous the Anarchy in the UK tour. A friendship between Lowry and The Clash ensued, and he was invited to accompany them on their 1979 US tour as the band's “official war artist”. -

Sexism Across Musical Genres: a Comparison

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 6-24-2014 Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison Sarah Neff Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Neff, Sarah, "Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison" (2014). Honors Theses. 2484. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2484 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: SEXISM ACROSS MUSICAL GENRES 1 Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison Sarah E. Neff Western Michigan University SEXISM ACROSS MUSICAL GENRES 2 Abstract Music is a part of daily life for most people, leading the messages within music to permeate people’s consciousness. This is concerning when the messages in music follow discriminatory themes such as sexism or racism. Sexism in music is becoming well documented, but some genres are scrutinized more heavily than others. Rap and hip-hop get much more attention in popular media for being sexist than do genres such as country and rock. My goal was to show whether or not genres such as country and rock are as sexist as rap and hip-hop. In this project, I analyze the top ten songs of 2013 from six genres looking for five themes of sexism. The six genres used are rap, hip-hop, country, rock, alternative, and dance. -

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

Performing Femininities and Doing Feminism Among Women Punk Performers in the Netherlands, 1976-1982

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Erasmus University Digital Repository Accepted manuscript of: Berkers, Pauwke. 2012. Rock against gender roles: Performing femininities and doing feminism among women punk performers in the Netherlands, 1976-1982. Journal of Popular Music Studies 24(2): 156-174. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1533-1598.2012.01323.x/full Rock against Gender Roles: Performing Femininities and Doing Feminism among Women Punk Performers in the Netherlands, 1976-1982 Pauwke Berkers ([email protected]) Department of Art and Culture Studies (ESHCC), Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands On November 8, 1980, a collective of women—inspired by the Rock Against Sexism movement in the U.K.—organized the Rock tegen de Rollen festival (“Rock Against Gender Roles”) the Netherlands’s city of Utrecht. The lineup consisted of six all-women punk and new wave bands (the Nixe, the Pin-offs, Pink Plastic & Panties,i the Removers, the Softies and the Broads) playing for a mixed gender audience. Similar to the Ladyfests two decades later, the main goal was to counteract the gender disparity of musical production (Aragon 77; Leonard, Gender 169). The organizers argued that: popular music is a men’s world as most music managers, industry executives and band members are male. Women are mainly relegated to the roles of singer or eye candy. However, women’s emancipation has also affected popular music as demonstrated by an increasing number of all-women bands playing excellent music. To showcase and support such bands we organized the Rock tegen de Rollen festival. -

Peter Hook L’Haçienda La Meilleure Façon De Couler Un Club

PETER HOOK L’HAÇIENDA LA MEILLEURE FAÇON DE COULER UN CLUB LE MOT ET LE RESTE PETER HOOK L’HAÇIENDA la meilleure façon de couler un club traduction de jean-françois caro le mot et le reste 2020 Ce livre est dédié à ma mère, Irene Hook, avec tout mon amour Reposez en paix : Ian Curtis, Martin Hannett, Rob Gretton, Tony Wilson et Ruth Polsky, sans qui l’Haçienda n’aurait jamais été construite LES COUPABLES Bien sûr que ça me poserait problème. Lorsque Claude Flowers m’a suggéré en 2003 d’écrire mes mémoires sur l’Haçienda, la première chose qui me vint à l’esprit est cette célèbre citation au sujet des années soixante : si vous vous en souvenez, c’est que vous n’y étiez pas. Tel était mon sentiment au sujet de l’Haç. J’allais donc avoir besoin d’un peu d’aide, et ce livre est le fruit d’un effort collectif. Claude a lancé les hostilités et m’a invité à me replonger dans de très nombreux souvenirs que je pensais avoir oubliés, tandis qu’Andrew Holmes m’a fourni ces « interludes » essentielles tout en se chargeant des démarches administratives. Je m’attribue le mérite de tout ce qui vous plaira dans ce livre. Si des passages vous déplaisent, c’est à eux qu’il faudra en vouloir. Avant-propos Nous avons vraiment fait n’importe quoi. Vraiment ? À y repenser aujourd’hui, je me le demande. Nous sommes en 2009 et l’Haçienda n’a jamais été aussi célèbre. En revanche, elle ne rapporte toujours pas d’argent ; rien n’a changé de ce côté-là. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

Put on Your Boots and Harrington!': the Ordinariness of 1970S UK Punk

Citation for the published version: Weiner, N 2018, '‘Put on your boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress' Punk & Post-Punk, vol 7, no. 2, pp. 181-202. DOI: 10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 Document Version: Accepted Version Link to the final published version available at the publisher: https://doi.org/10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 ©Intellect 2018. All rights reserved. General rights Copyright© and Moral Rights for the publications made accessible on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Please check the manuscript for details of any other licences that may have been applied and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. You may not engage in further distribution of the material for any profitmaking activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute both the url (http://uhra.herts.ac.uk/) and the content of this paper for research or private study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, any such items will be temporarily removed from the repository pending investigation. Enquiries Please contact University of Hertfordshire Research & Scholarly Communications for any enquiries at [email protected] 1 ‘Put on Your Boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress Nathaniel Weiner, University of the Arts London Abstract In 2013, the Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition of punk-inspired fashion entitled Punk: Chaos to Couture. -

Riotous Assembly: British Punk's Diaspora in the Summer of '81

Riotous assembly: British punk's diaspora in the summer of '81 Book or Report Section Accepted Version Worley, M. (2016) Riotous assembly: British punk's diaspora in the summer of '81. In: Andresen, K. and van der Steen, B. (eds.) A European Youth Revolt: European Perspectives on Youth Protest and Social Movements in the 1980s. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 217-227. ISBN 9781137565693 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/52356/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.palgrave.com/gb/book/9781137565693 Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Riotous Assembly: British punk’s diaspora in the summer of ‘81 Matthew Worley Britain’s newspaper headlines made for stark reading in July 1981.1 As a series of riots broke out across the country’s inner-cities, The Sun led with reports of ‘Race Fury’ and ‘Mob Rule’, opening up to provide daily updates of ‘Burning Britain’ as the month drew on.2 The Daily Mail, keen as always to pander a prejudice, described the disorder as a ‘Black War on Police’, bemoaning years of ‘sparing the rod’ and quoting those who blamed the riots on a ‘vociferous -

PUNK GRAPHICS. Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die

PUNK GRAPHICS. Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die PEDAGOGISCH DOSSIER INTRODUCTION 2 HELPFUL HINTS FOR YOUR VISIT & CONTENT OF THE KIT 3 1. COPY AND PASTE: THE APPROPRIATED IMAGE 4 2. CUT ‘N’ PASTE: COLLAGE & BRICOLAGE 6 3. RIDING A NEW WAVE 8 4. ECCENTRIC ALPHABETS: PUNK TYPOGRAPHY 9 5. COMIC RELIEF 11 6. SCARY MONSTERS & SUPER CREEPS 12 7. DO IT YOURSELF: ZINES & FLYERS 13 8. FOR ART’S SAKE 17 9. BACK TO THE FUTURE: RETRO GRAPHICS 20 10. AGIT-PROP: POWER TO THE PEOPLE 21 11. BELGIUM AIN’T FUN NO MORE 23 GLOSSARY 24 CREDITS 25 INFORMATION AND RESERVATION 26 PUNK GRAPHICS. Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die - Educational kit 1 INTRODUCTION More than forty years after punk exploded onto the music scenes of New York and London, its impact on the larger culture is still being felt. Born in a period of economic malaise, punk was a reaction, in part, to an increasingly formulaic rock music industry. Punk’s energy coalesced into a powerful subcultural phenomenon that transcended music to affect other fields, such as visual art, fashion, and graphic design. This exhibition explores the unique visual language of punk as it evolved in the United States and the United Kingdom through hundreds of its most memorable graphics—flyers, posters, albums, promotions, and zines. Drawn predominantly from the extensive collection of Andrew Krivine, PUNK GRAPHICS reveals punk as a range of diverse approaches and eclectic styles that resists its reduc- tion to just a handful of stereotypes. The Belgian appendix shows how these approaches and styles also inspired continental punk design. -

VIDEO and POP Paul Morley

May 1983 Marxism Today 37 VIDEO AND POP Paul Morley attention pop receives for multiples of wickedness, ridicule, discontent, eccentric ity, desire to thrive importantly in a genuinely popular context. Pop music can play a large part in the way numerous young people determine their right to desire and their need to question. It appeared that pop music's contem porary value was to be its creation or proposition of constant new values. Rock music — a period stretched from Elvis Presley to the last moment before The Sex Pistols coughed up Carry On Artaud — was easily appropriated by an establishment, the elegant apparatus of conservatism, that yearns for order. It was hoped that post-punk pop music, freed of the demands of over-excited hippies and usefully paranoiac, would evolve as some thing abstract, fluid, careering, irreverent, slippery, exaggerated — not on a revolu tionary mission, but non-static, not mean, a focus that supplies energy, as provocative and as changeable as essentially nostalgic twentieth century entertainment can be. A ringing variation. No destination, but a purpose. The video dumps us back into the most sinister part of the pop music game. In terms of pop as arousal the video takes us back to that moment before The Sex Pistols bawled louder than all the sur rounding banality. The moment of mundane disappointment. Some of us try an often brilliant best to resources can emerge that can help the The arrival, or at least the pop industry's prove to outsiders and cynics that pop audience release themselves from the misuse, of the video is a major reason, or music — what used to be known as rock unrelieving confinements of environment. -

Glam Rock by Barney Hoskyns 1

Glam Rock By Barney Hoskyns There's a new sensation A fabulous creation, A danceable solution To teenage revolution Roxy Music, 1973 1: All the Young Dudes: Dawn of the Teenage Rampage Glamour – a word first used in the 18th Century as a Scottish term connoting "magic" or "enchantment" – has always been a part of pop music. With his mascara and gold suits, Elvis Presley was pure glam. So was Little Richard, with his pencil moustache and towering pompadour hairstyle. The Rolling Stones of the mid-to- late Sixties, swathed in scarves and furs, were unquestionably glam; the group even dressed in drag to push their 1966 single "Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?" But it wasn't until 1971 that "glam" as a term became the buzzword for a new teenage subculture that was reacting to the messianic, we-can-change-the-world rhetoric of late Sixties rock. When T. Rex's Marc Bolan sprinkled glitter under his eyes for a TV taping of the group’s "Hot Love," it signaled a revolt into provocative style, an implicit rejection of the music to which stoned older siblings had swayed during the previous decade. "My brother’s back at home with his Beatles and his Stones," Mott the Hoople's Ian Hunter drawled on the anthemic David Bowie song "All the Young Dudes," "we never got it off on that revolution stuff..." As such, glam was a manifestation of pop's cyclical nature, its hedonism and surface show-business fizz offering a pointed contrast to the sometimes po-faced earnestness of the Woodstock era. -

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Punk-rock (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") London's burning TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The effervescence of New York's underground scene was contagious and spread to England with a 1976 tour of the Ramones that was artfully manipulated to start a fad (after the "100 Club Festival" of september 1976 that turned British punk-rock into a national phenomenon). In the USA the punk subculture was a combination of subterranean record industry and of teenage angst. In Britain it became a combination of fashion and of unemployment. Music in London had been a component of fashion since the times of the Swinging London (read: Rolling Stones). Punk-rock was first and foremost a fad that took over the Kingdom by storm. However, the social component was even stronger than in the USA: it was not only a generic malaise, it was a specific catastrophe. The iron rule of prime minister Margaret Thatcher had salvaged Britain from sliding into the Third World, but had caused devastation in the social fabric of the industrial cities, where unemployment and poverty reached unprecedented levels and racial tensions were brooding.