Muon to Electron Conversion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muon Decay 1

Muon Decay 1 LIFETIME OF THE MUON Introduction Muons are unstable particles; otherwise, they are rather like electrons but with much higher masses, approximately 105 MeV. Radioactive nuclear decays do not release enough energy to produce them; however, they are readily available in the laboratory as the dominant component of the cosmic ray flux at the earth’s surface. There are two types of muons, with opposite charge, and they decay into electrons or positrons and two neutrinos according to the rules + + µ → e νe ν¯µ − − µ → e ν¯e νµ . The muon decay is a radioactiveprocess which follows the usual exponential law for the probability of survival for a given time t. Be sure that you understand the basis for this law. The goal of the experiment is to measure the muon lifetime which is roughly 2 µs. With care you can make the measurement with an accuracy of a few percent or better. In order to achieve this goal in a conceptually simple way, we look only at those muons that happen to come to rest inside our detector. That is, we first capture a muon and then measure the elapsed time until it decays. Muons are rather penetrating particles, they can easily go through meters of concrete. Nevertheless, a small fraction of the muons will be slowed down and stopped in the detector. As shown in Figure 1, the apparatus consists of two types of detectors. There is a tank filled with liquid scintillator (a big metal box) viewed by two photomultiplier tubes (Left and Right) and two plastic scintillation counters (flat panels wrapped in black tape), each viewed by a photomul- tiplier tube (Top and Bottom). -

Muon Neutrino Mass Without Oscillations

The Distant Possibility of Using a High-Luminosity Muon Source to Measure the Mass of the Neutrino Independent of Flavor Oscillations By John Michael Williams [email protected] Markanix Co. P. O. Box 2697 Redwood City, CA 94064 2001 February 19 (v. 1.02) Abstract: Short-baseline calculations reveal that if the neutrino were massive, it would show a beautifully structured spectrum in the energy difference between storage ring and detector; however, this spectrum seems beyond current experimental reach. An interval-timing paradigm would not seem feasible in a short-baseline experiment; however, interval timing on an Earth-Moon long baseline experiment might be able to improve current upper limits on the neutrino mass. Introduction After the Kamiokande and IMB proton-decay detectors unexpectedly recorded neutrinos (probably electron antineutrinos) arriving from the 1987A supernova, a plethora of papers issued on how to use this happy event to estimate the mass of the neutrino. Many of the estimates based on these data put an upper limit on the mass of the electron neutrino of perhaps 10 eV c2 [1]. When Super-Kamiokande and other instruments confirmed the apparent deficit in electron neutrinos from the Sun, and when a deficit in atmospheric muon- neutrinos likewise was observed, this prompted the extension of the kaon-oscillation theory to neutrinos, culminating in a flavor-oscillation theory based by analogy on the CKM quark mixing matrix. The oscillation theory was sensitive enough to provide evidence of a neutrino mass, even given the low statistics available at the largest instruments. J. M. Williams Neutrino Mass Without Oscillations (2001-02-19) 2 However, there is reason to doubt that the CKM analysis validly can be applied physically over the long, nonvirtual propagation distances of neutrinos [2]. -

Muons: Particles of the Moment

FEATURES Measurements of the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon provide strong hints that the Standard Model of particle physics might be incomplete Muons: particles of the moment David W Hertzog WHEN asked what the most important strange, bottom and top; and six leptons, issue in particle physics is today, my ABORATORY namely the electron, muon and tau- colleagues offer three burning ques- L lepton plus their associated neutrinos. ATIONAL tions: What is the origin of mass? Why N A different set of particles is respon- is the universe made of matter and not sible for the interactions between these equal parts of matter and antimatter? ROOKHAVEN matter particles in the model. The elec- And is there any physics beyond the B tromagnetic interaction that binds elec- Standard Model? trons to nuclei results from the exchange The first question is being addressed of photons, whereas the strong force by a feverish quest to find the Higgs that binds quarks together inside neut- boson, which is believed to be respon- rons, protons and other hadrons is car- sible for the mass of fundamental par- ried by particles called gluons. The ticles. The Tevatron at Fermilab, which third force in the Standard Model – the is currently running, or the Large Had- weak nuclear interaction, which is re- ron Collider at CERN, which is due sponsible for radioactive decay – is car- to start experiments in 2007, should OWMAN ried by the W and Z bosons. B IPP eventually provide the answer to this R Physicists love the Standard Model, question by detecting the Higgs and but they do not like it. -

![Arxiv:1512.01765V2 [Physics.Atom-Ph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5627/arxiv-1512-01765v2-physics-atom-ph-1035627.webp)

Arxiv:1512.01765V2 [Physics.Atom-Ph]

August12,2016 1:27 WSPCProceedings-9.75inx6.5in Antognini˙ICOLS˙3 page 1 1 Muonic atoms and the nuclear structure A. Antognini∗ for the CREMA collaboration Institute for Particle Physics, ETH, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland Laboratory for Particle Physics, Paul Scherrer Institute, 5232 Villigen-PSI, Switzerland ∗E-mail: [email protected] High-precision laser spectroscopy of atomic energy levels enables the measurement of nu- clear properties. Sensitivity to these properties is particularly enhanced in muonic atoms which are bound systems of a muon and a nucleus. Exemplary is the measurement of the proton charge radius from muonic hydrogen performed by the CREMA collaboration which resulted in an order of magnitude more precise charge radius as extracted from other methods but at a variance of 7 standard deviations. Here, we summarize the role of muonic atoms for the extraction of nuclear charge radii, we present the status of the so called “proton charge radius puzzle”, and we sketch how muonic atoms can be used to infer also the magnetic nuclear radii, demonstrating again an interesting interplay between atomic and particle/nuclear physics. Keywords: Proton radius; Muon; Laser spectroscopy, Muonic atoms; Charge and mag- netic radii; Hydrogen; Electron-proton scattering; Hyperfine splitting; Nuclear models. 1. What atomic physics can do for nuclear physics The theory of the energy levels for few electrons systems, which is based on bound- state QED, has an exceptional predictive power that can be systematically improved due to the perturbative nature of the theory itself [1, 2]. On the other side, laser spectroscopy yields spacing between energy levels in these atomic systems so pre- cisely, that even tiny effects related with the nuclear structure already influence several significant digits of these measurements. -

![Explaining Muon G − 2 Data in the Μνssm Arxiv:1912.04163V3 [Hep-Ph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8110/explaining-muon-g-2-data-in-the-ssm-arxiv-1912-04163v3-hep-ph-1328110.webp)

Explaining Muon G − 2 Data in the Μνssm Arxiv:1912.04163V3 [Hep-Ph]

Explaining muon g 2 data in the µνSSM − Essodjolo Kpatcha∗a,b, Iñaki Lara†c, Daniel E. López-Fogliani‡d,e, Carlos Muñoz§a,b, and Natsumi Nagata¶f aDepartamento de Física Teórica, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM), Campus de Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain bInstituto de Física Teórica (IFT) UAM-CSIC, Campus de Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain cFaculty of Physics, University of Warsaw, Pasteura 5, 02-093 Warsaw, Poland dInstituto de Física de Buenos Aires UBA & CONICET, Departamento de Física, Facultad de Ciencia Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina e Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, 1107 Buenos Aires, Argentina fDepartment of Physics, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan Abstract We analyze the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon g 2 in the µνSSM. − This R-parity violating model solves the µ problem reproducing simultaneously neu- trino data, only with the addition of right-handed neutrinos. In the framework of the µνSSM, light left muon-sneutrino and wino masses can be naturally obtained driven by neutrino physics. This produces an increase of the dominant chargino-sneutrino loop contribution to muon g 2, solving the gap between the theoretical computation − and the experimental data. To analyze the parameter space, we sample the µνSSM using a likelihood data-driven method, paying special attention to reproduce the cur- rent experimental data on neutrino and Higgs physics, as well as flavor observables such as B and µ decays. We then apply the constraints from LHC searches for events with multi-leptons + MET on the viable regions found. They can probe these regions through chargino-chargino, chargino-neutralino and neutralino-neutralino pair pro- duction. -

A Practical Guide to the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source

A Practical Guide to the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source A Practical Guide to the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source 1 Contents Introduction 3 Production of neutrons and muons — in general 9 Production of neutrons and muons — at ISIS 15 Operating the machine 33 Neutron and muon techniques 41 Timeline 48 Initial concept and content: David Findlay ISIS editing and production team: John Thomason, Sara Fletcher, Rosie de Laune, Emma Cooper Design and Print: UKRI Creative Services 2 A Practical Guide to the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source WelcomeLate on the evening of 16 December 1984, a small group of people crammed into the ISIS control room to see history in the making – the generation of the first neutrons by the nascent particle accelerator. Back then, ISIS was a prototype, one of the first spallation sources built to generate neutrons for research. The machine included just three experimental instruments, although there were always ambitious plans for more! In 1987 three muon instruments expanded the range of tools available to the global scientific community. Since then we have built over 30 new instruments, not to mention a whole new target station! ISIS has grown in size and in strength to support a dynamic international user community of over 3,000 scientists, and over 15,000 papers have been published across a wide range of scientific disciplines. Spallation sources are widely established, a complementary tool to reactor based facilities and photon sources, forming a vital part of the global scientific infrastructure. This was made possible by the engineers, scientists and technicians who design, build and operate the machine. -

Study of Nuclear Properties with Muonic Atoms

EPJ manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Study of nuclear properties with muonic atoms A. Knecht1a, A. Skawran1;2b, and S. M. Vogiatzi1;2c 1 Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen, Switzerland 2 Institut f¨urTeilchen- und Astrophysik, ETH Z¨urich, Switzerland Received: date / Revised version: date Abstract. Muons are a fascinating probe to study nuclear properties. Muonic atoms can easily be formed by stopping negative muons inside a material. The muon is subsequently captured by the nucleus and, due to its much higher mass compared to the electron, orbits the nucleus at very small distances. During this atomic capture process the muon emits characteristic X-rays during its cascade down to the ground state. The energies of these X-rays reveal the muonic energy level scheme, from which properties like the nuclear charge radius or its quadrupole moment can be extracted. While almost all stable elements have been examined using muons, probing highly radioactive atoms has so far not been possible. The muX experiment has developed a technique based on transfer reaction inside a high pressure hydrogen/deuterium gas cell to examine targets available only in microgram quantities. PACS. 14.60. Ef Muons { 36.10.Dr Positronium, muonium, muonic atoms and molecules { 32.30.Rj X-ray spectra { 21.10.-k General and average properties of nuclei 1 Introduction Muons are fascinating particles with experiments being conducted in the context of particle, nuclear and atomic physics [1]. Additionally, also applied research is possible by measuring the spin precession and dynamics of muons inside materials through the µSR technique [2] thus probing the internal magnetic fields of the sample under study. -

Feynman Diagrams (Pdf)

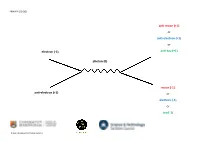

PRIMARY SCHOOL anti-muon (+1) or anti-electron (+1) or electron (-1) anti-tau (+1) photon (0) muon (-1) anti-electron (+1) or electron (-1) or tau (-1) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni HIGH SCHOOL anti-muon (……...) or anti-electron (……..) or electron (…….) anti-tau (……...) ………...…... (…...) muon (…….) anti-electron (……...) or electron (…….) or tau (……..) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni PRIMARY SCHOOL anti-up (-2/3) or anti-down (+1/3) or anti-strange (+1/3) or anti-beauty (+1/3) or anti-top (-2/3) or charm quark (+2/3) anti-charm (-2/3) gluon (0) up (+2/3) or down (-1/3) anti-charm quark (-2/3) or strange (-1/3) or beauty (-1/3) or top (+2/3) or charm (+2/3) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni HIGH SCHOOL anti-up (……….) or anti-down (……...) or anti-strange (……...) or anti-beauty (……...) or anti-top (……...) or charm quark (……...) anti-charm (……...) ………...…... (…...) up (……...) or down (……...) or anti-charm quark (……..) strange (……...) or beauty (……...) or top (……...) or charm (……...) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni PRIMARY SCHOOL anti-up (-2/3) or anti-charm (-2/3) muon (-1) W minus (-1) down (-1/3) muon neutrino (0) or strange (-1/3) or beauty (-1/3) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni HIGH SCHOOL anti-up (……...) or anti-charm (……...) muon (……...) ………...…... (…...) down (……...) muon neutrino (……...) or strange (……...) or beauty (……...) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni PRIMARY SCHOOL electron neutrino (0) or muon neutrino (0) or tau neutrino (0) tau (-1) Z (0) electron anti-neutrino (0) anti-tau (+1) or muon anti-neutrino (0) or tau anti-neutrino (0) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni HIGH SCHOOL electron neutrino (……...) or muon neutrino (……...) or tau neutrino (……...) tau (……...) …………. -

The Nuclear Physics of Muon Capture

Physics Reports 354 (2001) 243–409 The nuclear physics of muon capture D.F. Measday ∗ University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Rd., Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z1 Received December 2000; editor: G:E: Brown Contents 4.8. Charged particles 330 4.9. Fission 335 1. Introduction 245 5. -ray studies 343 1.1. Prologue 245 5.1. Introduction 343 1.2. General introduction 245 5.2. Silicon-28 350 1.3. Previous reviews 247 5.3. Lithium, beryllium and boron 360 2. Fundamental concepts 248 5.4. Carbon, nitrogen and oxygen 363 2.1. Properties of the muon and neutrino 248 5.5. Fluorine and neon 372 2.2. Weak interactions 253 5.6. Sodium, magnesium, aluminium, 372 3. Muonic atom 264 phosphorus 3.1. Atomic capture 264 5.7. Sulphur, chlorine, and potassium 377 3.2. Muonic cascade 269 5.8. Calcium 379 3.3. Hyperÿne transition 275 5.9. Heavy elements 383 4. Muon capture in nuclei 281 6. Other topics 387 4.1. Hydrogen 282 6.1. Radiative muon capture 387 4.2. Deuterium and tritium 284 6.2. Summary of g determinations 391 4.3. Helium-3 290 P 6.3. The (; e±) reaction 393 4.4. Helium-4 294 7. Summary 395 4.5. Total capture rate 294 Acknowledgements 396 4.6. General features in nuclei 300 References 397 4.7. Neutron production 311 ∗ Tel.: +1-604-822-5098; fax: +1-604-822-5098. E-mail address: [email protected] (D.F. Measday). 0370-1573/01/$ - see front matter c 2001 Published by Elsevier Science B.V. -

The Rest Masses of the Electron and Muon and of the Stable Mesons And

The rest masses of the electron and muon and of the stable mesons and baryons E.L. Koschmieder Center for Statistical Mechanics The University of Texas at Austin, Austin TX 78712, USA e-mail: [email protected] The rest masses of the electron, the muon and of the stable mesons and baryons can be explained, within 1% accuracy, with the standing wave model, which uses only photons, neutrinos, charge and the weak nuclear force. We do not need hypothetical particles for the explanation of the masses of the electron, muon, mesons and baryons. We have determined the rest masses of the electron-, muon- and tau neutrinos and found that the mass of the electron neutrino is equal to the fine structure constant times the mass of the muon neutrino. Key words: Neutrino masses, electron mass, muon mass, meson masses, baryon masses. PACS numbers: 14.40.-n; 14.60.-z; 14.60.Pq. Introduction The so-called “Standard Model” of the elementary particles has, until now, not come up with a precise theoretical determination of the masses of either the mesons and baryons or of the leptons, which means that neither the mass of the fundamental electron nor the mass of the fundamental proton have been explained. The quarks, which have been introduced by Gell-Mann [1] forty years ago, are said to explain the mesons and baryons. But the standard model does not explain neither the mass, nor the charge, nor the spin of the particles, the three fundamental time-independent properties of arXiv:physics/0602037v4 [physics.gen-ph] 30 Jul 2007 the particles. -

ELEMENTARY PARTICLES in PHYSICS 1 Elementary Particles in Physics S

ELEMENTARY PARTICLES IN PHYSICS 1 Elementary Particles in Physics S. Gasiorowicz and P. Langacker Elementary-particle physics deals with the fundamental constituents of mat- ter and their interactions. In the past several decades an enormous amount of experimental information has been accumulated, and many patterns and sys- tematic features have been observed. Highly successful mathematical theories of the electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions have been devised and tested. These theories, which are collectively known as the standard model, are almost certainly the correct description of Nature, to first approximation, down to a distance scale 1/1000th the size of the atomic nucleus. There are also spec- ulative but encouraging developments in the attempt to unify these interactions into a simple underlying framework, and even to incorporate quantum gravity in a parameter-free “theory of everything.” In this article we shall attempt to highlight the ways in which information has been organized, and to sketch the outlines of the standard model and its possible extensions. Classification of Particles The particles that have been identified in high-energy experiments fall into dis- tinct classes. There are the leptons (see Electron, Leptons, Neutrino, Muonium), 1 all of which have spin 2 . They may be charged or neutral. The charged lep- tons have electromagnetic as well as weak interactions; the neutral ones only interact weakly. There are three well-defined lepton pairs, the electron (e−) and − the electron neutrino (νe), the muon (µ ) and the muon neutrino (νµ), and the (much heavier) charged lepton, the tau (τ), and its tau neutrino (ντ ). These particles all have antiparticles, in accordance with the predictions of relativistic quantum mechanics (see CPT Theorem). -

HIGGS BOSON MUON COLLIDER FACTORY: H0, A, H STUDIES * D

HIGGS BOSON MUON COLLIDER FACTORY: h0, A, H STUDIES * D. Cline#, X. Ding, J. Lederman, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA Abstract models predicted a Higgs mass of 120 GeV. Thus the With the recent hints of the Higgs boson from the LHC evidence for a 125 GeV Higgs is a surprise. and a mass near 125 GeV/c we re-propose to study and We have devised a ring cooler for 6D cooling [2]. The build a muon collider Higgs factory to study the Higgs in key idea behind a muon collider Higgs factory is to be the S channel [1]. This was first proposed in 1992 by the able to measure the exact mass and width in this channel. first author. It is essential to study the Higgs boson for We showed in 1993-1994 that this is possible. clues to new physics. The formation of the DOE MAP In Reference 4 we follow a discussion of the type of program, recent advances in 6D µ cooling methods, physics process that a muon collider exceeds at carrying simulation, and targeting make this a feasible project to out. As shown in Figures 1 and 2 the low mass h0 Higgs is initiate at this time. This collider would fit into the FNAL very narrow. Reference 4 suggests an energy scan strategy site. to find this narrow resonance with a muon collider. THE FIRST STUDIES OF MUON COLLIDER HIGGS FACTORY 1992-1994 The early studies of muon collider focussed on an S channel Higgs Factory (h0) [2]. The major scientific goal is to measure the exact h0 mass and the width in the S channel.