Later Bronze Age and Iron Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June to August 2021

PROGRAMME : JUNE, JULY & AUGUST 2021 WEB SITE: www.verwoodramblers.org.uk GENTLE EXERCISE FRESH AIR GOOD COMPANY Our club, formed in 1972, offers three walks of 3-4 miles, 5-6 miles, and 9-10 miles, each week, enjoying the stunning downland of Cranborne Chase, woodland and heath in the New Forest, and coastal paths of the Purbecks and World Heritage Jurassic Coast. “TRY BEFORE YOU BUY” - WHY NOT JOIN US FOR A TASTER CALL 01202 826403 NB 1: Walks will be subject to current Covid secure rambling guidelines, see separate file. NB 2: CANCELLED WALKS: If you have any doubts, for whatever reason, that a walk will go ahead as published, IT IS YOUR RESPONSIBILITY TO CONFIRM BY CONTACTING THE LEADER before going to the starting point. NB 3: DOGS: Members are not encouraged to bring dogs, as some members may feel discomfort. Walks invariably pass through areas containing livestock. If brought they should be on a lead at all times and under control. Damage by dogs is not covered by the Club’s insurance policy and would be the owner’s responsibility. All mileages are approximate. JUNE 1 Tues CAR PARK on B3082 Near Badbury Rings 10:00 Exp 118 GR ST966 023 N.B. this is the small free CP opposite the left turn to White Mill, Sturminster Marshall 3.6 mls Gently undulating figure of 8 walk to the Rings 1 steady incline, 1 short hill, no stiles, mud possible. 2 Wed GARSTON/PRIBDEAN WOOD CP 10:00 Exp 118 GR SU 003 195 5 mls Deanland, Barber’s and Great Shaftesbury Coppice, Shermel Gate. -

Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 60 (2017) 715-787 brill.com/jesh Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records Jonathan S. Tenney Cornell University [email protected] Abstract To date, servility and servile systems in Babylonia have been explored with the tradi- tional lexical approach of Assyriology. If one examines servility as an aggregate phe- nomenon, these subjects can be investigated on a much larger scale with quantitative approaches. Using servile populations as a point of departure, this paper applies both quantitative and qualitative methods to explore Babylonian population dynamics in general; especially morbidity, mortality, and ages at which Babylonians experienced important life events. As such, it can be added to the handful of publications that have sought basic demographic data in the cuneiform record, and therefore has value to those scholars who are also interested in migration and settlement. It suggests that the origins of servile systems in Babylonia can be explained with the Nieboer-Domar hy- pothesis, which proposes that large-scale systems of bondage will arise in regions with * This was written in honor, thanks, and recognition of McGuire Gibson’s efforts to impart a sense of the influence of aggregate population behavior on Mesopotamian development, notably in his 1973 article “Population Shift and the Rise of Mesopotamian Civilization”. As an Assyriology student who was searching texts for answers to similar questions, I have occasionally found myself in uncharted waters. Mac’s encouragement helped me get past my discomfort, find the data, and put words on the page. The necessity of assembling Mesopotamian “demographic” measures was something made clear to me by the M.A.S.S. -

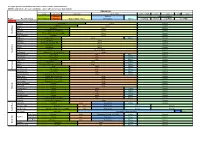

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Middlewich Before the Romans

MIDDLEWICH BEFORE THE ROMANS During the last few Centuries BC, the Middlewich area was within the northern territories of the Cornovii. The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe and their territories were extensive: they included Cheshire and Shropshire, the easternmost fringes of Flintshire and Denbighshire and parts of Staffordshire and Worcestershire. They were surrounded by the territories of other similar tribal peoples: to the North was the great tribal federation of the Brigantes, the Deceangli in North Wales, the Ordovices in Gwynedd, the Corieltauvi in Warwickshire and Leicestershire and the Dobunni to the South. We think of them as a single tribe but it is probable that they were under the control of a paramount Chieftain, who may have resided in or near the great hill‐fort of the Wrekin, near Shrewsbury. The minor Clans would have been dominated by a number of minor Chieftains in a loosely‐knit federation. There is evidence for Late Iron Age, pre‐Roman, occupation at Middlewich. This consists of traces of round‐ houses in the King Street area, occasional finds of such things as sword scabbard‐fittings, earthenware salt‐ containers and coins. Taken together with the paleo‐environmental data, which hint strongly at forest‐clearance and agriculture, it is possible to use this evidence to create a picture of Middlewich in the last hundred years or so before the Romans arrived. We may surmise that two things gave the locality importance; the salt brine‐springs and the crossing‐points on the Dane and Croco rivers. The brine was exploited in the general area of King Street, and some of this important commodity was traded far a‐field. -

Higher Nansloe Farm Helston Cornwall

Higher Nansloe Farm Helston Cornwall Post-Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design for Coastline Design and Build Ltd CA Project: 889011 CA Report: 18038 May 2019 Higher Nansloe Farm Helston Cornwall Post-Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design CA Project: 889011 CA Report: 18038 Jonathan Orellana, Project Officer prepared by and Jonathan Hart, Senior Publications Officer date 8 May 2019 checked by Jonathan Hart, Senior Publications Officer date 8 May 2019 approved by Karen Walker, Principal Post-Excavation Manager signed 08/05/2019 date issue 01 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. 1 Higher Nansloe Farm, Helston, Cornwall: Post-Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design © Cotswold Archaeology CONTENTS SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................... 4 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 5 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................. 7 3 METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................................. 8 4 RESULTS ......................................................................................................................... -

Ulug-Depe and the Transition Period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia

Ulug-depe and the transition period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia. A tribute to V.I. Sarianidi Johanna Lhuillier To cite this version: Johanna Lhuillier. Ulug-depe and the transition period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia. A tribute to V.I. Sarianidi . Dubova, N.A., Antonova, E.V., Kozhin, P.M., Kosarev, M.F., Muradov, R.G., Sataev, R.M. & Tishkin A.A. Transactions of Margiana Archaeological Expedition, To the memory of Professor Viktor Sarianidi, 6, Staryj Sad, pp.509-521, 2016, 978-5-89930-150-6. halshs-01534928 HAL Id: halshs-01534928 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01534928 Submitted on 8 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N.N. MIKLUKHO-MAKLAY INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY OF RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES MARGIANA ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION ALTAY STATE UNIVERSITY TRANSACTIONS OF MARGIANA ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION Volume 6 To the Memory of Professor Victor Sarianidi Editorial board N.A. Dubova (editor in chief), E.V. Antonova, P.M. Kozhin, M.F. Kosarev, R.G. Muradov, R.M. Sataev, A.A. Tishkin Moscow 2016 Туркменистан, Гонур-депе, 9 октября 2005 г. -

X the Late Bronze Age Ceramic Traditions of the Syrian Jazirah

Originalveröffentlichung in: al-Maqdissī – Valérie Matoïan – Christophe Nicolle (Hg.), Céramique de l'âge du bronze en Syrie, II, L'Euphrate et la région de Jézireh (Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 180), Beyrouth 2007, S. 231-291 X The Late Bronze Age Ceramic Traditions of the Syrian Jazirah Peter Pfalzner THE PERIODIZATION SYSTEM AND THE QUESTION clearly circumscribed factors in the history and chronology OF CHRONOLOGICAL TERMINOLOGY of the Syrian Jazirah. Furthermore, through their specific political and economical organization they considerably The second half of the 2nd mill, BC in Syria has been influenced the material culture of the Syrian Jazirah. As chronologically labeled either in terms of the system of a consequence, both periods reveal a distinct ceramic "metal epochs" as the Late Bronze Age I and II or else repertoire. These two archaeological phases and ceramic labeled according to a culturally and geographically traditions can thus be labeled "Mittani" and "Middle oriented terminology as the "Middle-Syrian"' period Assyrian". (ca 1600/1530-1200/1100 BC). With regard to the strong In order to avoid misconceptions of these terms, it is geographical differentiation of material culture, especially important to note that the terms "Mittani" and "Middle pottery, within Syria to be observed in many periods, it is Assyrian ceramic period" do not imply an ethnic assignment advisable to introduce a chronological periodization on a of the pottery concerned. They have a purely political- regional scale. For the Syrian Jazirah, a region with very geographical significance. This is to say that any of the distinct ceramic repertoires through all phases from the Late Bronze Age Jazirah population groups - for example Early Bronze to the Iron Age, the "Jazirah chronological 3 Hurrians , Assyrians, Aramaeans, etc. -

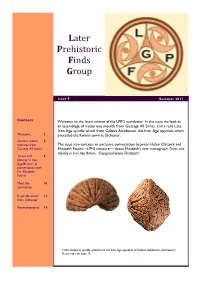

LPFG Newsletter Issue 9

Later Prehistoric Finds Group Issue 9 Summer 2017 Contents Welcome to the latest edition of the LPFG newsletter. In this issue we look at an assemblage of mysterious moulds from Gussage All Saints, and a rare Late Iron Age spindle whorl from Calleva Atrebatum, the Iron Age oppidum which Welcome 2 preceded the Roman town at Silchester. Curious mould 3 matrices from The issue also contains an exclusive conversation between Helen Chittock and Gussage All Saints Elizabeth Foulds—LPFG treasurer—about Elizabeth’s new monograph, Dress and Identity in Iron Age Britain. Congratulations Elizabeth! ‘Dress and 6 Identity in Iron Age Britain’: A conversation with Dr. Elizabeth Foulds Meet the 10 committee A spindle whorl 12 from Silchester Announcements 14 Half a biconical spindle wheel from the Iron Age oppidum of Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester). Read more on page 12. Page 2 Welcome The Later Prehistoric Finds Group was established in 2013, and welcomes anyone with an interest in prehistoric artefacts, especially small finds from the Bronze and Iron Ages. We hold an annual conference and produce two newsletters a year. Membership is currently free; if you would like to join the group, please e-mail [email protected]. We are a new group, and we are hoping that more researchers interested in prehistoric artefacts will want to join us. The group has opted for a loose committee structure that is not binding, and a list of those on the steering committee, along with contact details, can be found on our website: https://sites.google.com/site/laterprehistoricfindsgroup/home. Anna Booth is the current Chair, and Dot Boughton is Deputy. -

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

Bronze Age Iron Age Anglo-Saxons the Mayflower Thames Tunnel The

Monday 11th – Friday 15th May 2020 History Think about what the word ancient means. Which description below do you think is the most accurate? 1. Ancient means a period of time five years ago. 2. Ancient means a period of time five hundred years ago. 3. Ancient means a period of time five thousand years ago. This half term, we will be looking at a time in history when people lived many thousands of years ago. People who lived many thousands of years ago lived in what we call ancient times. There were three main time periods (long lengths of time) in ancient times in Britain (the country we live in). We call these periods of time the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. Bronze and iron are types of metal. Why do you think these periods of time were named after metals? Look at the pictures below. Can you match the ancient artefact (object) to the right time period? What clues can you see? We will be looking in more detail at the Bronze Age and Iron Age – they both happened after the Stone Age. The Bronze Age began around 2,100BCE (over 4,000 years ago). It lasted for around 1500 years until 750BCE when the Iron Age began. Bronze Age Anglo-Saxons Thames Tunnel 2,100BCE 750BCE 55BCE 0 410 1620 1825 1940 2020 Iron Age The Mayflower The Blitz Just like the Stone Age when early humans made tools from stone, the Bronze Age was called that because humans started making tools from…bronze! The Bronze Age started at different times around the world – depending on when humans in different countries discovered how to make bronze by mixing other metals together. -

Dorset History Centre

GB 0031 MK Dorset History Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 5598 The National Archives DORSET RECORD OFFICE MK Documents presented to the Dorchester County Museum by Messrs. Traill, Castleman-Smith and Wilson in 1954. DLEDS. N " J Bundle No Date Description of Documents of Documents AFFPUDDLE Tl 1712 Messuage, Cottage and land. 1 BSLCHALWELL and IB3ERT0I? a T2 1830 Land in Fifehead Quinton in Belchalwell and messuage called Quintons in Ibberton; part of close called Allinhere in Ibberton. (Draftsj* 2 BELCHALWELL * * T3 1340 i Cottage (draft); with residuary account of Mary Robbins. 2 BERE REGIS K T4 1773-1781 Cottage and common rights at Shitterton, 1773; with papers of Henry Hammett of the same, including amusing letter complaining of 'Divels dung1 sold to hira, 1778-1731. 11 Messuage at Rye Hill X5 1781-1823 3 a T6 1814-1868 2 messuages, at some time before 1853 converted into one, at iiilborne Stilehara. ' 9 T7 1823-1876 Various properties including cottage in White Lane, Milborne Stileham. 3 BLAHDFOIiD FORUM T8 1641-1890 Various messuages in Salisbury Street, including the Cricketers Arms (1826) and the houses next door to the Bell Inn. (1846,1347) 14 *T9 1667-1871 Messuages in Salisbury Street, and land "whereon there , stood before the late Dreadful Fire a messuage1 (1736) in sane street, 1667-1806, with papers,; 1316-71. 21 TIG 168^6-1687/8 Messuage in Salisbury Street (Wakeford family) A Til 1737-1770 Land in Salisbury Street. (Bastard family) J 2 212 1742-1760 Land in Salisbury Street, with grant to rest timbers on a wall there.