Isle of Man, Viking Myths and Rituals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

Agenda: 7 March 2018

Malew Parish Commissioners Clerk: Mr B.J. Powell Commissioners’ Offices Main Road Ballasalla IM9 2RQ 02 March 2018 Dear Sir/Madam I beg to notify you the Ordinary Meeting of the Board will be held in the above Office on Wednesday 07 March 2018 at 09.00. Yours faithfully Barry J Powell Clerk to the Commissioners AGENDA MINUTES • Minutes of the meeting held on 07 February 2018. Planning 18/00122/C Langness Cottage & Barrule Cottage, Lower Mr & Mrs A Ballantyne Ballachrink, Ballamodha. Additional use of tourist accommodation as residential accommodation 18/00127/B Unit 22 Block D Balthane Industrial Estate Ballasalla Place T/A The Conversion from storage use to a dog grooming Fairy Dogmother business & store 18/00130/B Walton House, Bridge Road Mr & Mrs C Bateson Alterations to window positions (forming amendments to works constructed under 16/00850/B) retrospective 1 18/00161/B Field 432440 & part field 432475 adjacent Billown Colas Quarry, Foxdale Road. Extension to existing quarry 18/00166/B Manella Kerrowkeil Road, Grenaby Mr & Mrs J Paradise Replacement of existing annex roof with tiled roof Treasury • 1st Supplemental List 2018. DOI • Public Rights of Way: Policy & Strategy 2018-2028. Sleepwell Hotels Youth & Junior Tour Cycle Races 4 – 6 May 2018 • Provisional event schedule. Invoices and payments to be approved by the Board Diary dates - Ordinary Meeting Wednesday 04 April 9 a.m. 2 Minutes for the Ordinary Meeting of Malew Parish Commissioners Wednesday 7 February 2018 Meeting Commenced: 09.00 Present: Mrs B Brereton, Mrs J Knighton, Mrs M Mansfield, Mr J Brereton Apologies: Mr R Pilling In Attendance: Mr B Powell – Clerk . -

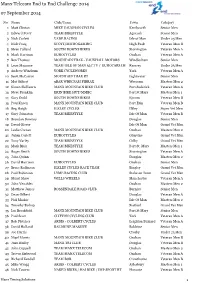

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014 No Name Club/Team Town Category 1 Matt Clinton MIKE VAUGHAN CYCLES Kenilworth Senior Men 2 Edward Perry TEAM BIKESTYLE Agneash Senior Men 3 Nick Corlett VADE RACING Isle of Man Under 23 Men 4 Nick Craig SCOTT/MICROGAMING High Peak Veteran Men B 5 Steve Calland SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 6 Mark Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Veteran Men A 7 Ben Thomas MOUNTAIN TRAX - VAUXHALL MOTORS Windlesham Senior Men 8 Leon Mazzone TEAMCYCLING ISLE TEAM OF MAN 3LC.TV / EUROCARS.IM Ramsey Under 23 Men 9 Andrew Windrum YORK CYCLEWORKS York Veteran Men A 10 Scott McCarron MOUNTAIN TRAX RT Lightwater Senior Men 11 Mat Gilbert 9BAR WRECSAM FIBRAX Wrecsam Masters Men 2 12 Simon Skillicorn MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Soderick Veteran Men A 13 Steve Franklin ERIN BIKE HUT/MMBC Port St Mary Masters Men 1 14 Gary Dodd SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Epsom Veteran Men B 15 Paul Kneen MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Erin Veteran Men B 16 Reg Haigh ILKLEY CYCLES Ilkley Super Vet Men 17 Gary Johnston TEAM BIKESTYLE Isle Of Man Veteran Men B 18 Brendan Downey Douglas Senior Men 19 David Glover Isle Of Man Grand Vet Men 20 Leslie Corran MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Onchan Masters Men 2 21 Julian Corlett EUROCYCLES Glenvine Grand Vet Men 22 Tony Varley TEAM BIKESTYLE Colby Grand Vet Men 23 Mark Blair TEAM BIKESTYLE Port St. Mary Masters Men 1 24 Roger Smith SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 25 John Quinn Douglas Masters Men 2 26 David Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Senior Men 27 Bruce Rollinson ILKLEY CYCLES RACE -

GD No 2017/0037

GD No: 2017/0037 isle of Man. Government Reiltys ElIan Vannin The Council of Ministers Annual Report Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee .Duty 2017 The Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Piemorials Committee Foreword by the Hon Howard Quayle MHK, Chief Minister To: The Hon Stephen Rodan MLC, President of Tynwald and the Honourable Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled. In November 2007 Tynwald resolved that the Council of Ministers consider the establishment of a suitable body for the preservation of War Memorials in the Isle of Man. Subsequently in October 2008, following a report by a Working Group established by Council of Ministers to consider the matter, Tynwald gave approval to the formation of the Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee. I am pleased to lay the Annual Report before Tynwald from the Chair of the Committee. I would like to formally thank the members of the Committee for their interest and dedication shown in the preservation of Manx War Memorials and to especially acknowledge the outstanding voluntary contribution made by all the membership. Hon Howard Quayle MHK Chief Minister 2 Annual Report We of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee I am very honoured to have been appointed to the role of Chairman of the Committee. This Committee plays a very important role in our community to ensure that all War Memorials on the Isle of Man are protected and preserved in good order for generations to come. The Committee continues to work closely with Manx National Heritage, the Church representatives and the Local Authorities to ensure that all memorials are recorded in the Register of Memorials. -

ATTACHMENT for ISLE of MAN 1. QI Is Subject to the Following Laws

ATTACHMENT FOR ISLE OF MAN 1. QI is subject to the following laws and regulations of Isle of Man governing the requirements of QI to obtain documentation confirming the identity of QI=s account holders. (i) Drug Trafficking Offences Act 1987. (ii) Prevention of Terrorism Act 1990. (iii) Criminal Justice Act 1990. (iv) Criminal Justice Act 1991. (v) Drug Trafficking Act 1996. (vi) Criminal Justice (Money Laundering Offences) Act 1998. (vii) Anti-Money Laundering Code 1998. (viii) Anti-Money Laundering Guidance Notes. 2. QI represents that the laws identified above are enforced by the following enforcement bodies and QI shall provide the IRS with an English translation of any reports or other documentation issued by these enforcement bodies that are relevant to QI=s functions as a qualified intermediary. (i) Financial Supervision Commission. (ii) Financial Crime Unit of Isle of Man Constabulary. (iii) Attorney General for the Isle of Man. 3. QI represents that the following penalties apply to failure to obtain, maintain, and evaluate documentation obtained under the laws and regulations identified in item 1 above. Imprisonment for a term of up to fourteen years, or a fine or both, and imposition of conditions on a license or the revocation of a license granted by the Isle of Man Financial Supervision Commission. 4. QI shall use the following specific documentary evidence (and also any specific documentation added by an amendment to this item 4 as agreed to by the IRS) to comply with section 5 of this Agreement, provided that the following specific documentary evidence satisfies the requirements of the laws and regulations identified in item 1 above. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Manx Traditional Dance Revival 1929 to 1960

‘…while the others did some capers’: the Manx Traditional Dance revival 1929 to 1960 By kind permission of Manx National Heritage Cinzia Curtis 2006 This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Arts in Manx Studies, Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool. September 2006. The following would not have been possible without the help and support of all of the staff at the Centre for Manx Studies. Special thanks must be extended to the staff at the Manx National Library and Archive for their patience and help with accessing the relevant resources and particularly for permission to use many of the images included in this dissertation. Thanks also go to Claire Corkill, Sue Jaques and David Collister for tolerating my constant verbalised thought processes! ‘…while the others did some capers’: The Manx Traditional Dance Revival 1929 to 1960 Preliminary Information 0.1 List of Abbreviations 0.2 A Note on referencing 0.3 Names of dances 0.4 List of Illustrations Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Methodology 1 1.2 Dancing on the Isle of Man in the 19th Century 5 Chapter 2: The Collection 2.1 Mona Douglas 11 2.2 Philip Leighton Stowell 15 2.3 The Collection of Manx Dances 17 Chapter 3: The Demonstration 3.1 1929 EFDS Vacation School 26 3.2 Five Manx Folk Dances 29 3.3 Consolidating the Canon 34 Chapter 4: The Development 4.1 Douglas and Stowell 37 4.2 Seven Manx Folk Dances 41 4.3 The Manx Folk Dance Society 42 Chapter 5: The Final Figure 5.1 The Manx Revival of the 1970s 50 5.2 Manx Dance Today 56 5.3 Conclusions -

Manx Farming Communities and Traditions. an Examination of Manx Farming Between 1750 and 1900

115 Manx Farming Communities and Traditions. An examination of Manx farming between 1750 and 1900 CJ Page Introduction Set in the middle of the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man was far from being an isolated community. Being over 33 miles long by 13 miles wide, with a central mountainous land mass, meant that most of the cultivated area was not that far from the shore and the influence of the sea. Until recent years the Irish Sea was an extremely busy stretch of water, and the island greatly benefited from the trade passing through it. Manxmen had long been involved with the sea and were found around the world as members of the British merchant fleet and also in the British navy. Such people as Fletcher Christian from HMAV Bounty, (even its captain, Lieutenant Bligh was married in Onchan, near Douglas), and also John Quilliam who was First Lieutenant on Nelson's Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar, are some of the more notable examples. However, it was fishing that employed many Manxmen, and most of these fishermen were also farmers, dividing their time between the two occupations (Kinvig 1975, 144). Fishing generally proved very lucrative, especially when it was combined with the other aspect of the sea - smuggling. Smuggling involved both the larger merchant ships and also the smaller fishing vessels, including the inshore craft. Such was the extent of this activity that by the mid- I 8th century it was costing the British and Irish Governments £350,000 in lost revenue, plus a further loss to the Irish administration of £200,000 (Moore 1900, 438). -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Grid Export Data

Accommodation for Guest Required to Self-Isolate February 2021 Accommodation Name Classification Type Address 1 Address 2 Town Post Code Email Address Main Phone Bedrooms Bedspaces Rating 1 Barnagh Barns Self Catering 1 Barnagh Barns Rhencullen Kirk Michael IM6 2HB [email protected] 07624 480803 2 4 4 Star Gold 13 Willow Terrace Self Catering 13 Willow Terrace Douglas IM1 3HA [email protected] 07624 307575 2 4 Rating Pending Apartment 1 - Derby Court Self Catering Flat 1 Derby Court 42 The Promenade Castletown IM9 1BG [email protected] 07624 493181 2 4 4 Star Arrandale Apartments - Flat 1 Self Catering 24 Hutchinson Square Douglas IM2 4HP [email protected] 01624 674907 1 2 3 Star Arrandale Apartments - Flat 2 Self Catering 24 Hutchinson Square Douglas IM2 4HP [email protected] 01624 674907 1 2 3 Star Arrandale Apartments - Flat 3 Self Catering 24 Hutchinson Square Douglas IM2 4HP [email protected] 01624 674907 2 3 3 Star Arrandale Apartments - Flat 4 Self Catering 24 Hutchinson Square Douglas IM2 4HP [email protected] 01624 674907 1 2 3 Star Arrandale Apartments - Flat 5 Self Catering 24 Hutchinson Square Douglas IM2 4HP [email protected] 01624 674907 1 2 3 Star Arrandale Apartments - Flat 6 Self Catering 24 Hutchinson Square Douglas IM2 4HP [email protected] 01624 674907 1 2 3 Star Arrandale Apartments - Flat 7 Self Catering 24 Hutchinson Square Douglas IM2 4HP [email protected] 01624 674907 1 2 3 Star At Caledonia Guest House Caledonia 17 Palace Terrace Douglas IM2 4NE [email protected] 01624 624569 20 50 -

School Catchment Areas Order 2O7o

Statutory Document No. 100210 EDUCATION ACT 2OO7 SCHOOL CATCHMENT AREAS ORDER 2O7O Comíng into operøtion L lønuøry 201.0 The Department of Education and Children makes this Order under section 15(a) of the Education Act 2001r. 1 Title This Order is the Sdrool Catchment Areas Order 20L0 and shall come into operation on the l,stlaruary 2011, 2 Commencement This order comes into operation on the l't January 2011 3 Interpretation In this Order "the order maps" means lhreL2maps arurexed to this Order and entitled "Mup No.1 referred to in the School Catchrrrent Areas Order 2010" to "Map No.12 refer¡ed to in the Sclrool Catchment Areas Order 2010 4 Catchment areas of primary schools (1) Úr relation to eadr primary sdrool specified in colrrmn 1 of Sdredule L, the area shown edged with a thick yellow line on one or more of the order maps and indicated by the corresponding nurnber specified in colrrmn 2 of that Sdredule is designated as the catchment area of that sdrool. (2) The parishes constituted for purposes of the Roman Catholic Churdr and annexed to St Anthony's, StJoseph's and StMary's churdres are designated as the catdrment area of St Mary's Roman Catholic School, Douglas. (3) There are no designated catctLment areas for St Thomas' Churdr of England Primary School, Douglas and the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, StJohn's. t 2oo1 c.33 Price: f,2.00 1 5 Catchment areas of secondary schools (1) Subject to paragraphs (2) and (3), in relation to eadr secondary school specified in column 1 of Sdredule 2, the areas designated by article 2 as the catdrment areas of the corresponding primary sdrools specified in column 2 of that Schedule are together designated as the catchment area of that school. -

October 2007 Kiaull Manninagh Jiu

Manx Music Today October 2007 Kiaull Manninagh Jiu Bree 2007 a manx feis for 11 to 16 year olds On Saturday 27th and Sunday 28th of October, another technique and performance skills. They will then opt to take Bree weekend will take place at Douglas Youth Centre on sessions in either accompanying & rhythm instruments Kensington Road. Inspired by the Feiséan nan Gael (e.g. guitar, piano, bodhran etc.); song-writing and movement in Scotland, Bree is a Manx Gaelic youth arts arranging or Manx dancing. All of the students will take movement for 11 to 16 year olds consisting of workshops in Manx Gaelic and learn to work in musical groups. music, language and dance. The first Bree [Manx for ‘vitality’] took place in October last year and proved to be The Bree workshops are led by local Manx musicians, not only educational, but fantastic fun for both students and dancers and language experts. They will take place tutors and a great place to make new friends, form new between 10am and 3.30pm on both days but will finish with bands and be really creative with Manx culture [see page 3 a concert for family and friends at the end of the second for a new song composed by a Bree member last year]. day from 3.30pm. Bree is organised and funded by the Since the last weekend festival of workshops, a monthly Manx Heritage Foundation and the Youth Service. youth music session has taken place at various venues around the Island. An application form is included at the end of this newsletter.