Questions on the British H-Bomb by Robert Standish Norris June 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

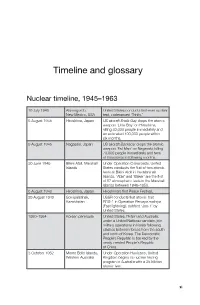

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Information Regarding Radiation Reports Commissioned by Atomic Weapons

6';ZeKr' LOOSE MIN= C 31 E Tot' Task Force Commander, Operation Grapple 'X' A 0 \ Cloud Sampling 1. It is agreed that the meteorological conditions at Christmas Island, although ideal in sane ways, pose oonsiderable problems in others. First31„ the tropopause at Christmas Island varies between 55,000 and 59,000 ft; thin is in contrast to the tropopause in the U.S. Eniwetok area which is more usually around 45,000 ft. and, under conditions of small, i.e. under two megaton bursts, may give quite different cloud ooncentrations. In the Eniwetok area the mushroom tends to leave some cloud at tropopause and then go on up producing a small sample at tropopause level, but the main body being much higher does not cause the problem of "shine" that is caused at Christmas Island where the difference of 12,000 to 15,000 extra feet in tropopause level tends to result in the upward rise of the oloud immediately after this level being slower and the spread immediate thereby causing an embarrassing amount of "shine" to the cloud samplers who must be over 50,000 ft. The other thing which I think must be borne in mind is the temperature at the 60,000 ft. level in the Christmas Island area. If this is minus 90° or over, trouble may well be expected from "flame-out" in rocket assisted turbo-jet aircraft. It is frequently minus 82° at 53,000 ft. 2. We have tended to find in past trials that the area between the base of the cloud and the sea is, to all intents and purposes, free from significant radiation. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

The Threat of Nuclear Proliferation: Perception and Reality Jacques E

ROUNDTABLE: NONPROLIFERATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY The Threat of Nuclear Proliferation: Perception and Reality Jacques E. C. Hymans* uclear weapons proliferation is at the top of the news these days. Most recent reports have focused on the nuclear efforts of Iran and North N Korea, but they also typically warn that those two acute diplomatic headaches may merely be the harbingers of a much darker future. Indeed, foreign policy sages often claim that what worries them most is not the small arsenals that Tehran and Pyongyang could build for themselves, but rather the potential that their reckless behavior could catalyze a process of runaway nuclear proliferation, international disorder, and, ultimately, nuclear war. The United States is right to be vigilant against the threat of nuclear prolifer- ation. But such vigilance can all too easily lend itself to exaggeration and overreac- tion, as the invasion of Iraq painfully demonstrates. In this essay, I critique two intellectual assumptions that have contributed mightily to Washington’s puffed-up perceptions of the proliferation threat. I then spell out the policy impli- cations of a more appropriate analysis of that threat. The first standard assumption undergirding the anticipation of rampant pro- liferation is that states that abstain from nuclear weapons are resisting the dictates of their narrow self-interest—and that while this may be a laudable policy, it is also an unsustainable one. According to this line of thinking, sooner or later some external shock, such as an Iranian dash for the bomb, can be expected to jolt many states out of their nuclear self-restraint. -

Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592

Technical Data Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592 Topic Page Description 2 Heater Element Selection Procedure 2 Index to Heater Element Selection Tables 5 Heater Element Selection Tables 6 Additional Resources These documents contain additional information concerning related products from Rockwell Automation. Resource Description Industrial Automation Wiring and Grounding Guidelines, publication 1770-4.1 Provides general guidelines for installing a Rockwell Automation industrial system. Product Certifications website, http://www.ab.com Provides declarations of conformity, certificates, and other certification details. You can view or download publications at http://www.rockwellautomation.com/literature/. To order paper copies of technical documentation, contact your local Allen-Bradley distributor or Rockwell Automation sales representative. For Application on Bulletin 100/500/609/1200 Line Starters Heater Element Specifications Eutectic Alloy Overload Relay Heater Elements Type J — CLASS 10 Type P — CLASS 20 (Bul. 600 ONLY) Type W — CLASS 20 Type WL — CLASS 30 Note: Heater Element Type W/WL does not currently meet the material Type W Heater Elements restrictions related to EU ROHS Description The following is for motors rated for Continuous Duty: For motors with marked service factor of not less than 1.15, or Overload Relay Class Designation motors with a marked temperature rise not over +40 °C United States Industry Standards (NEMA ICS 2 Part 4) designate an (+104 °F), apply application rules 1 through 3. Apply application overload relay by a class number indicating the maximum time in rules 2 and 3 when the temperature difference does not exceed seconds at which it will trip when carrying a current equal to 600 +10 °C (+18 °F). -

The Fallacy of Nuclear Deterrence

THE FALLACY OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE LCol J.P.P. Ouellet JCSP 41 PCEMI 41 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs do not represent Department of National Defence or et ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used Ministère de la Défense nationale ou des Forces without written permission. canadiennes. Ce papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2015. le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2015. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 41 – PCEMI 41 2014 – 2015 EXERCISE SOLO FLIGHT – EXERCICE SOLO FLIGHT THE FALLACY OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE LCol J.P.P. Ouellet “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas necessarily reflect the policy or the nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion opinion of any agency, including the d'un organisme quelconque, y compris le Government of Canada and the gouvernement du Canada et le ministère Canadian Department of National de la Défense nationale du Canada. -

Bob Farquhar

1 2 Created by Bob Farquhar For and dedicated to my grandchildren, their children, and all humanity. This is Copyright material 3 Table of Contents Preface 4 Conclusions 6 Gadget 8 Making Bombs Tick 15 ‘Little Boy’ 25 ‘Fat Man’ 40 Effectiveness 49 Death By Radiation 52 Crossroads 55 Atomic Bomb Targets 66 Acheson–Lilienthal Report & Baruch Plan 68 The Tests 71 Guinea Pigs 92 Atomic Animals 96 Downwinders 100 The H-Bomb 109 Nukes in Space 119 Going Underground 124 Leaks and Vents 132 Turning Swords Into Plowshares 135 Nuclear Detonations by Other Countries 147 Cessation of Testing 159 Building Bombs 161 Delivering Bombs 178 Strategic Bombers 181 Nuclear Capable Tactical Aircraft 188 Missiles and MIRV’s 193 Naval Delivery 211 Stand-Off & Cruise Missiles 219 U.S. Nuclear Arsenal 229 Enduring Stockpile 246 Nuclear Treaties 251 Duck and Cover 255 Let’s Nuke Des Moines! 265 Conclusion 270 Lest We Forget 274 The Beginning or The End? 280 Update: 7/1/12 Copyright © 2012 rbf 4 Preface 5 Hey there, I’m Ralph. That’s my dog Spot over there. Welcome to the not-so-wonderful world of nuclear weaponry. This book is a journey from 1945 when the first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert to where we are today. It’s an interesting and sometimes bizarre journey. It can also be horribly frightening. Today, there are enough nuclear weapons to destroy the civilized world several times over. Over 23,000. “Enough to make the rubble bounce,” Winston Churchill said. The United States alone has over 10,000 warheads in what’s called the ‘enduring stockpile.’ In my time, we took care of things Mano-a-Mano. -

The Man Behind an Identity in Quantum Electrodynamics by F

The man behind an identity in quantum electrodynamics by F. J. Duarte Introduction The 6th of May, 2010, marks the 10th anniversary of the passing of John Clive Ward a quiet genius of physics whose ideas and contributions helped shape the post-war quantum era. Since John was an Australian citizen it is only appropriate to remember him in the pages of this journal. First, as a manner of introduction, I will outline John’s most salient contributions. Then, I will attempt a description of the physicists, teacher, and friend that I was privileged to know. Physics theoreticians thus producing a series of brilliant papers on: In an approximated chronological order the contributions of the Ising Model (Kac and Ward, 1952), quantum solid-state John Ward began with a paper published (with Maurice L. physics (Ward and Wilks, 1952), quantum statistics (Montroll H. Pryce) in Nature as part of his doctoral research at Oxford and Ward, 1958), and Fermion theory (Luttinger and Ward, (Pryce and Ward, 1947). This was a solution to a problem, 1960). His last paper was on the Dirac equation and higher that according to John was posed by Dirac, and that J. A. symmetries (Ward, 1978). Wheeler had tried to solve (Ward, 2004). The suggestion to tackle this problem was made by Pryce (a former student of In a piece written in an Oxford publication it was once stated R. H. Fowler and John’s supervisor). This had to do with that Ward “has contributed deeply to an astonishingly broad the decay of γ particles and the emission of two correlated range of theoretical physics: statistical mechanics, plasma photons in opposite directions. -

Some Aspects of the Theory of Heavy Ion Collisions

Some Aspects of the Theory of Heavy Ion Collisions Franc¸ois Gelis Institut de Physique Th´eorique CEA/Saclay, Universit´eParis-Saclay 91191, Gif sur Yvette, France June 16, 2021 Abstract We review the theoretical aspects relevant in the description of high energy heavy ion collisions, with an emphasis on the learnings about the underlying QCD phenomena that have emerged from these collisions. 1 Introduction to heavy ion collisions Elementary forces in Nature The interactions among the elementary constituents of matter are divided into four fundamental forces: gravitation, electromagnetism, weak nuclear forces and strong nuclear forces. All these interactions except gravity have a well tested a microscopic quantum description in terms of local gauge theories, in which the elementary matter fields are spin-1=2 fermions, interacting via the exchange of spin-1 bosons. In this framework, a special role is played by the Higgs spin-0 boson (the only fundamental scalar particle in the Standard Model), whose non-zero vacuum expectation value gives to all the other fields a mass proportional to their coupling to the Higgs. The discovery of the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider in 2012 has so far confirmed all the Standard Model expectations. In this picture, gravity has remained a bit of an outlier: even though the classical field theory of gravitation (general relativity) has been verified experimentally with a high degree of precision (the latest of these verifications being the observation of gravitational waves emitted during the merger of massive compact objects - black holes or arXiv:2102.07604v3 [hep-ph] 15 Jun 2021 neutron stars), the quest for a theory of quantum gravity has been inconclusive until now (and possible experimental probes are far out of reach for the foreseeable future). -

Science, Technology and Medicine In

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1017/9781139044301.012 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Edgerton, D., & Pickstone, J. V. (2020). The United Kingdom. In H. R. Slotten, R. L. Numbers, & D. N. Livingstone (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Science: Modern Science in National, Transnational, and Global Context (Vol. 8, pp. 151-191). (Cambridge History of Science; Vol. 8). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139044301.012 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

60 Anniversary of Valiant's First Flight

17th May 2011 60th Anniversary of Valiant’s First Flight First Flight 18th May 1951 Wednesday 18th May 2011 will mark the 60th Anniversary of the first flight of the Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant. Part of the Royal Air Forces V-Bomber nuclear deterrent during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to make it into the air, when prototype WB210 took to the skies on 18th May 1951. The Royal Air Force Museum Cosford is home to the world’s only complete example, Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant B (K).1 XD818. The Valiant is on display in the Museums award winning National Cold War Exhibition, the only place in the world where you can see all three of Britain’s V-Bombers: Vulcan, Victor and Valiant on display together under one roof. This British four jet bomber went into active RAF service in 1955 and played a significant role during the Cold War period. With a wingspan of 114ft, over 108ft in length and a height of over 32ft, the Valiant had a bomb capacity of a 10,000lb nuclear bomb or 21 x 1,000lb conventional bombs. In total 107 aircraft were built, each carrying a crew of five including two pilots, two navigators and an air electronics officer. The type was retired from RAF service in 1965 due to structural problems. RAF Museum Cosford Curator, Al McLean says: "The Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to enter service, the first to drop a nuclear weapon and the first to go into combat. -

NEMA Motor Control

Bulletin Eutectic Alloy Overload Relays Heater Elements Selection For Application on Bulletin 100/500/609/1200 Line Starters Eutectic Alloy Overload Relay Heater Elements Heater Element Selection Type J — CLASS 10 Table of Contents 0 Type P — CLASS 20 (Bul. 600 ONLY) Type W — CLASS 20 Overload Relay Type WL — CLASS 30 Class Designation...... this page Heater Element Selection ....................... this page 1 Type W Heater Elements Ambient Temperature Correction..................... this page Time — Current Characteristics............ 1-169 2 Index to Heater Element Selection Tables ............................. 1-170 3 Description The following is for motors rated for Continuous Duty: For motors with marked service factor of not less than 1.15, or Overload Relay Class Designation motors with a marked temperature rise not over +40 °C United States Industry Standards (NEMA ICS 2 Part 4) designate an (+104 °F), apply application rules 1 through 3. Apply application 4 overload relay by a class number indicating the maximum time in rules 2 and 3 when the temperature difference does not exceed seconds at which it will trip when carrying a current equal to 600 +10 °C (+18 °F). When the temperature difference is greater, see percent of its current rating. below. A Class 10 overload relay will trip in 10 seconds or less at a current 1. The Same Temperature at the Controller and the Motor — equal to 600 percent of its rating. Select the “Heater Type Number” with the listed “Full Load 5 Amperes” nearest the full load value shown on the motor A Class 20 overload relay will trip in 20 seconds or less at a current nameplate.