Report of the Task Force on Space January 8,1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 106, May 2006

37 th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference THE CONFERENCE IN REVIEW Attendance at the 37th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) set yet another record for this conference, with 1546 participants from 24 countries attending the meeting held at the South Shore Harbour Resort and Conference Center in League City, Texas, on March 13–17, 2006 (see inset for attendance statistics). Rearrangement of the confi guration of the meeting rooms, along with additional overfl ow seating, allowed conference organizers and staff to accommodate the marked increase in attendance, thereby being able to maintain the current meeting venue and hence the low registration fee, which enables the high number of student attendees. LPSC continues to be recognized among the international science community as the most important planetary conference in the world, and this year’s meeting substantiated the merit of that reputation. More than 1400 abstracts were submitted in consideration for presentation at the conference, and hundreds of planetary scientists and students attended both oral and poster sessions focusing on such diverse topics as the Moon, Mars, Mercury, and Venus; outer planets and satellites; meteorites; comets, asteroids, and other small bodies; Limpacts; interplanetary dust particles and presolar grains; origins of planetary systems; planetary formation and early evolution; and astrobiology. Sunday night’s registration and reception were again held at the Center for Advanced Space Studies, which houses the Lunar and Planetary Institute. Featured on Sunday night was an open house for the display of education and public outreach activities and programs. Highlights of the conference program, established by the program committee under the guidance of co-chairs Dr. -

Next Steps in the Military Uses of Space

Mastering the Ultimate HighGround Next Steps in the Military Uses of Space Benjamin S. Lambeth Prepared for the United States Air Force R Project AIR FORCE Approved for public release; distrubution unlimited The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lambeth, Benjamin S. Mastering the ultimate high ground : next steps in the military uses of space / Benjamin S. Lambeth. p. cm. “MR-1649.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8330-3330-1 (pbk.) 1. Astronautics, Military—United States. 2. United States. Air Force. 3. United States—Military policy. I. Rand Corporation. II.Title. UG1523.L35 2003 358'.8'0973—dc21 2002155704 RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. © Copyright 2003 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 2003 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 201 North Craig Street, Suite 202, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-1516 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Email: [email protected] PREFACE This study assesses the military space challenges facing the Air Force and the nation in light of the watershed findings and recom- mendations of the congressionally mandated Space Commission that were released in January 2001. -

Project Mercury Fact Sheet

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Langley Research Center Hampton, Virginia 23681-0001 April 1996 FS-1996-04-29-LaRC ___________________________________________________________________________ Langley’s Role in Project Mercury Project Mercury Thirty-five years ago on May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard was propelled into space aboard the Mercury capsule Freedom 7. His 15-minute suborbital flight was part of Project Mercury, the United States’ first man-in-space program. The objectives of the Mer- cury program, eight unmanned flights and six manned flights from 1961 to 1963, were quite specific: To orbit a manned spacecraft around the Earth, investigate man’s ability to function in space, and to recover both man and spacecraft safely. Project Mercury included the first Earth orbital flight made by an American, John Glenn in February 1962. The five-year program was a modest first step. Shepard’s flight had been overshadowed by Russian Yuri Gagarin’s orbital mission just three weeks earlier. President Kennedy and the Congress were NASA Langley Research Center photo #59-8027 concerned that America catch up with the Soviets. Langley researchers conduct an impact study test of the Seizing the moment created by Shepard’s success, on Mercury capsule in the Back River in Hampton, Va. May 25, 1961, the President made his stirring chal- lenge to the nation –– that the United States commit Langley Research Center, established in 1917 itself to landing a man on the moon and returning as the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics him to Earth before the end of the decade. Apollo (NACA) Langley Memorial Aeronautical Labora- was to be a massive undertaking –– the nation’s tory, was the first U.S. -

National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide

NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 —Tep-nm.T7ymqtmthitmemf- (u) National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide For Automatic Declassification Of 25-Year-Old Information Version 1.0 2008 Edition Approved: Scott F. Large Director DECL ON: 25x1, 20590201 DRV FROM: NRO Classification Guide 6.0, 20 May 2005 NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 (U) Table of Contents (U) Preface (U) Background 1 (U) General Methodology 2 (U) File Series Exemptions 4 (U) Continued Exemption from Declassification 4 1. (U) Reveal Information that Involves the Application of Intelligence Sources and Methods (25X1) 6 1.1 (U) Document Administration 7 1.2 (U) About the National Reconnaissance Program (NRP) 10 1.2.1 (U) Fact of Satellite Reconnaissance 10 1.2.2 (U) National Reconnaissance Program Information 12 1.2.3 (U) Organizational Relationships 16 1.2.3.1. (U) SAF/SS 16 1.2.3.2. (U) SAF/SP (Program A) 18 1.2.3.3. (U) CIA (Program B) 18 1.2.3.4. (U) Navy (Program C) 19 1.2.3.5. (U) CIA/Air Force (Program D) 19 1.2.3.6. (U) Defense Recon Support Program (DRSP/DSRP) 19 1.3 (U) Satellite Imagery (IMINT) Systems 21 1.3.1 (U) Imagery System Information 21 1.3.2 (U) Non-Operational IMINT Systems 25 1.3.3 (U) Current and Future IMINT Operational Systems 32 1.3.4 (U) Meteorological Forecasting 33 1.3.5 (U) IMINT System Ground Operations 34 1.4 (U) Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Systems 36 1.4.1 (U) Signals Intelligence System Information 36 1.4.2 (U) Non-Operational SIGINT Systems 38 1.4.3 (U) Current and Future SIGINT Operational Systems 40 1.4.4 (U) SIGINT -

Download Chapter 123KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 13 FFinalinal TTributeribute VVolol 113.indd3.indd 258258 33/23/10/23/10 33:42:35:42:35 PMPM Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 13 ROBERT C. SEAMANS, JR. 1918–2008 Elected in 1968 “For engineering design and development of airborne systems; technical leadership in the nation’s space program.” BY SHEILA E. WIDNALL ROBERT C. SEAMANS, JR. one of the nation’s outstanding engineering leaders, senior administrator for several federal agencies, and former president of NAE, died on June 28, 2008, at the age of 89. Associate administrator, then associate and deputy administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) from 1960 to 1968, Dr. Seamans helped lead the nation’s space program from its infancy to its triumphant Apollo successes. He was secretary of the Air Force from 1969 until 1973 and became president of NAE in 1973. In 1974, he became the fi rst administrator of the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA), predecessor to the U.S. Department of Energy. Robert Seamans was born on October 30, 1918, in Salem, Massachusetts. He attended Lenox School, in Lenox, Massachusetts, and earned a B.S. in engineering from Harvard in 1939, an M.S. in aeronautics and astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1942, and a D.S. in instrumentation from MIT in 1951. As part of his doctoral work, he assisted Charles Stark Draper, a pioneer in gyroscope guidance, in developing tracking systems that enabled Navy ships to target enemy planes. Those systems were later used for missile navigation and eventually to guide Apollo astronauts to the Moon. -

Spies and Shuttles

Spies and Shuttles University Press of Florida Florida A&M University, Tallahassee Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers Florida International University, Miami Florida State University, Tallahassee New College of Florida, Sarasota University of Central Florida, Orlando University of Florida, Gainesville University of North Florida, Jacksonville University of South Florida, Tampa University of West Florida, Pensacola SPIE S AND SHUTTLE S NASA’s Secret Relationships with the DoD and CIA James E. David Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C., in association with University Press of Florida Gainesville · Tallahassee · Tampa · Boca Raton Pensacola · Orlando · Miami · Jacksonville · Ft. Myers · Sarasota Copyright 2015 by Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper All photographs courtesy of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. This book may be available in an electronic edition. 20 19 18 17 16 15 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data David, James E., 1951– author. Spies and shuttles : NASA’s secret relationships with the DOD and CIA / James David. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8130-4999-1 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-8130-5500-8 (ebook) 1. Astronautics—United States —History. 2. Astronautics, Military—Government policy—United States. 3. United States. National Aeronautics and Space Administration—History. 4. United States. Department of Defense—History. -

Robert Channing Seamans, Jr

Daniel Guggenheim Medal MEDALIST FOR 1995 For lifelong technical contributions and technical leadership in academia, industry and government as NASA Deputy Administrator during the Apollo program and in several other government positions. ROBERT CHANNING SEAMANS, JR. Robert Seamans played a major role in the Apollo Program, which brought preeminence to the United States as a “manned space faring nation.” He graduated from Harvard with the class of 1940. He and a fellow classmate decided to look into the possibilities of an advanced degree in engineering from MIT. Seamans was admitted as graduate student Professor Draper’s multi-disciplinary program called “The Instrumentation Program” program. This was the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship between Draper and Seamans, who ultimately earned an SM and ScD in Instrumentation in 1951. His thesis involved the dynamic coupling between an airborne gunsight and airplane dynamics. Typically, for a Draper supervised thesis, Seamans verified his calculations with a flight test program, in which he innovated the use of a rapid change of the position of a control surface followed by a rapid restoration to the original position, which enabled him to determine the aircraft dynamics from flight data. This control motion has become standard and is called a “doublet.” During WWII Seamans was an instructor in the Department of Aeronautics and on the staff of the Draper Laboratory. He taught members of the Navy V-7 program and worked on or led several important classified fire control projects for the Navy and the Army Air Corps. In 1950 he became program manager of a joint MIT-lndustry project to develop an air to air missile, which was called the ‘Meteor.’ In 1954 he was hired by RCA and established the Airborne Systems Laboratory. -

The Future Is Now at Johnson Space Center

THE FUTURE IS NOW AT JOHNSON SPACE CENTER By Mike Coats, Center Director, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA has continued to explore and discover space for fifty years, and since its establishment in 1961, the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) has been a major contributor to the agency’s success. Originally called the Manned Spacecraft Center, this federal institution was born out of the early space program’s need for a location to house the Space Task Group at the beginning of the Apollo Program. After President John F.Kennedy announced that the U.S. would put a man on the moon by the end of the decade, the site in Houston was selected to provide test facilities and research laboratories suitable to mount an expedition to the moon. Since then, the Center has continued to make history in space exploration, highlighted by scientific and technological advancements as well as engineering triumphs. This rich tradition continues each and every day, and here is a summary of how it is reflected. From JSC’s inception, it was to be the primary center for U.S. space missions involving astronauts; however, through the years JSC has expanded its role in a number of aspects in space exploration. These include serving as the lead NASA center for the International Space Station (ISS)—a sixteen-nation, U.S.-led collaborative effort that is constructing and supporting the largest, most powerful, complex human facility to ever operate in space. Home to NASA’s astronaut corps, JSC trains space explorers from the U.S. and our space station partner nations, preparing these individuals as crew members for space shuttle missions and long-duration Expedition missions on the ISS. -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, INDUSTRIAL AREA, HABS FL-583-D HANGAR S HABS FL-583-D (John F. Kennedy Space Center) Cape Canaveral Brevard County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, INDUSTRIAL AREA HANGAR S HABS NO. FL-583-D Location: Building 1726, Hangar Road, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS) Industrial Area. USGS Cape Canaveral, Florida, Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates E 540530 N 3151415 Zone 17, NAD 1983 Present Owner: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Present Use: Vacant Significance: Hangar S served as the home of NASA’s Pre-Flight Operations Division of Project Mercury from 1959-1963. In Hangar S, the Mercury spacecraft capsules were received, tested, and prepared for flight. The hangar housed astronauts’ pre-flight training and preparation, including capsule simulator training, flight pressure suit tests, flight plan development, and communications training. The astronaut crew quarters were located on the second floor of the hangar’s south wing. Hangar S is directly associated with events that led to the first U.S. manned sub-orbital space flight of Alan B. Shepard in 1961 and the orbital flight of John Glenn in 1962. Hangar S was determined eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) at the national level of significance under Criterion A in the area of Space Exploration. Hangar S is also NRHP eligible under Criterion B for association with the training activities of the original Mercury Seven astronauts, including Alan B. -

Historical Narrative Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas

HISTORICAL NARRATIVE LYNDON B. JOHNSON SPACE CENTER HOUSTON, TEXAS Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) officially opened in June 1964 as the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC). This approximately 1,620-acre facility is located about 25 miles from downtown Houston, Texas, in Harris County. Many of the buildings are specialized facilities devoted to spacecraft systems, materials research and development, and astronaut training. JSC also includes the Sonny Carter Training Facility, located roughly 4.5 miles to the northwest of the center, close to Ellington Field. Opened in 1997, this facility is situated on land acquired through a lease/purchase agreement with the McDonnell Douglas Corporation. In addition, NASA JSC owns some of the facilities at Ellington Field, which are generally where the aircraft used for astronaut training are stored and maintained. The origins of JSC can be traced to the summer of 1958 when three executives of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), Dr. Hugh L. Dryden, Dr. Robert R. Gilruth, and Dr. Abe Silverstein, began to formulate a space program.1 Almost immediately, Gilruth began to focus on manned spaceflight, and subsequently convened a group of his associates at Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, in Hampton, Virginia. This group compiled the basics of what would become Project Mercury, the first U.S. manned space program. Eight days following the activation of NASA (October 1, 1958), with the approval of NASA’s first administrator, Dr. T. Keith Glennan, the Space Task Group (STG) was created to implement this program.2 The group was formally established on November 3, 1958, with Gilruth named as Project Manager. -

Memorial Tributes: Volume 13

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/12734 SHARE Memorial Tributes: Volume 13 DETAILS 338 pages | 6 x 9 | HARDBACK ISBN 978-0-309-14225-0 | DOI 10.17226/12734 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK National Academy of Engineering FIND RELATED TITLES Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 13 Memorial Tributes NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING FFrontront MMatter.inddatter.indd i 33/23/10/23/10 33:40:26:40:26 PMPM Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 13 FFrontront MMatter.inddatter.indd iiii 33/23/10/23/10 33:40:27:40:27 PMPM Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 13 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Memorial Tributes Volume 13 THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. 2010 FFrontront MMatter.inddatter.indd iiiiii 33/23/10/23/10 33:40:27:40:27 PMPM Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 13 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-14225-0 International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-14225-3 Additional copies of this publication are available from: The National Academies Press 500 Fifth Street, N.W. -

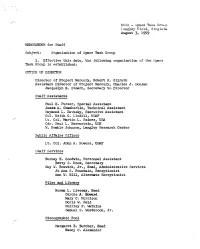

Space Task Group August 3, 1959

NASA - Space Task Gro,,p l.angley Field, Virginia. August}, 1959 MEMOP.ANDUM for Staff Subject: Organization ot Space Task Group l. Effective this date, the following organization of the Space Task Group is established: OFFICE OF DIRECTOR Director of Project Merci.try, Robert R. Gilruth Assistant Director of Project Mercury, Charles J. Donlan Jacquelyn B. Stearn, Secretary to Director Staff Assistants Paul E. Purser, Special Assistant James A. Chamberl.in, Technical Assistant Raymond L. Zavasky, Executive Assistant Col. Keith G. Lindell, USAF Lt. Col. Martin L. Raines, USA Cdr. Paul L. Ha.venstein, US?l w. Kemble Johnson, Langley Research Center Public Affairs Officer Lt. Col. John A. Powers, USAF Staff Services Burney H. Goodvin, Personnel Assistant Betty s. Knox, Secretary Guy w. Boswick, Jr., Head, Administrative Services Jo Ann s. Fountain, Receptionist Ann w. Hill., AlterDate Receptionist Files and Library Norma L. Livesay, Head Carole A. Howard Mary c. Morrison Doris w. Reid Shirley P. wa.tkins Semuel s. Westbrook, Jr. Stenographic Pool Margaret B. Bu:rcher, Head Nancy C, Alexander - 2 - Nor.ma C. Eacho Irene J. Hel.terbran Ann W. Hill Patricia H. Murpey Technical Services Jack A. Kinzler, Technical. Services Assistant 18vid L, McCraw Orrin A. Wobig Astrooa.uts and Training Group Col. Keith G, Lindell, USAF, Head Lt. Col.. William K. DousJ.,as, USAF, Flight Surgeon Lt. Robert B. Voas, USN, Training Officer (Warren J, North will continue to participate in all astronaut activities as representative of the Office of Space Flight Development) Astronauts Lt, Malcolm s. carpenter, USN Capt. Leroy G. Cooper, Jr., USAF Lt, Col.