Biotic Recoveries from Mass Extinctions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extent and Duration of Marine Anoxia During the Frasnian– Famennian (Late Devonian) Mass Extinction in Poland, Germany, Austria and France

This is a repository copy of Extent and duration of marine anoxia during the Frasnian– Famennian (Late Devonian) mass extinction in Poland, Germany, Austria and France. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/297/ Article: Bond, D.P.G., Wignall, P.B. and Racki, G. (2004) Extent and duration of marine anoxia during the Frasnian– Famennian (Late Devonian) mass extinction in Poland, Germany, Austria and France. Geological Magazine, 141 (2). pp. 173-193. ISSN 0016-7568 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756804008866 Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Geol. Mag. 141 (2), 2004, pp. 173–193. c 2004 Cambridge University Press 173 DOI: 10.1017/S0016756804008866 Printed in the United Kingdom Extent and duration of marine anoxia during the Frasnian– Famennian (Late Devonian) mass extinction in Poland, Germany, Austria and France DAVID BOND*, PAUL B. WIGNALL*† & GRZEGORZ RACKI‡ *School of Earth Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK ‡Department of Palaeontology and Stratigraphy, University of Silesia, ul. Bedzinska 60, PL-41-200 Sosnowiec, Poland (Received 25 March 2003; accepted 10 November 2003) Abstract – The intensity and extent of anoxia during the two Kellwasser anoxic events has been investigated in a range of European localities using a multidisciplinary approach (pyrite framboid assay, gamma-ray spectrometry and sediment fabric analysis). -

The Truong Son, Loei-Phetchabun, and Kontum Terranes in Indochina: Provenance, Rifting, and Collisions

REVIEW published: 28 May 2021 doi: 10.3389/feart.2021.603565 The Truong Son, Loei-Phetchabun, and Kontum Terranes in Indochina: Provenance, Rifting, and Collisions Clive Burrett 1, Mongkol Udchachon 1,2* and Hathaithip Thassanapak 2 1 Palaeontological Research and Education Centre, Mahasarakham University, Mahasarakham, Thailand, 2 Applied Palaeontology and Biostratigraphy Research Unit, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Mahasarakham University, Mahasarakham, Thailand The three main regions of Indochina are defined as the Truong Son, Loei-Phetchabun, and Kontum terranes. The aim of this review is to integrate numerous petrological studies with sedimentary, palaeontological, and provenance studies in order to construct a preliminary tectonic model which shows the terranes docked in the earliest Carboniferous (Truong Son with Loei-Phetchabun) and in the Permian (Kontum). The Kontum Terrane is characterized by Proterozoic magmatism, mid-Ordovician to Early Devonian granites, and Permian charnockites. Major carbonate platforms developed in the Givetian to earliest Tournaisian on Truong Son and from the Visean to mid-Permian across Truong Edited by: Son and Loei-Phetchabun terranes. The Truong Son has Silurian granites and a Basilios Tsikouras, Late Ordovician to Silurian magmatic arc along its southern and western borders Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Brunei caused by subduction of oceanic lithosphere, the remnants of which are now partially Reviewed by: Antonio Pedrera, preserved in the Loei and Tamky sutures. A region to the east of the Loei Suture in Instituto Geológico y Minero de the Loei Foldbelt has a similar-age volcanic arc extending northwards into Laos and España (IGME), Spain Sergio Llana-Fúnez, is included in Truong Son. -

Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian Mass Extinction: Comparing Brachiopod Faunas

Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian mass extinction: Comparing brachiopod faunas PAUL COPPER Copper, P. 1998. Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian mass extinction: Comparing bra- chiopod faunas.- Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 43,2,137-154. The Frasnian-Famennian (F-F) mass extinctions saw the global loss of all genera belonging to the tropically confined order Atrypida (and Pentamerida): though Famen- nian forms have been reported in the literafure, none can be confirmed. Losses were more severe during the Givetian (including the extinction of the suborder Davidsoniidina, and the reduction of the suborder Lissatrypidina to a single genus),but ońgination rates in the remaining suborder surviving into the Frasnian kept the group alive, though much reduced in biodiversity from the late Earb and Middle Devonian. In the terminal phases of the late Palmatolepis rhenana and P linguifurmis zones at the end of the Frasnian, during which the last few Atrypidae dechned, no new genera originated, and thus the Atrypida were extĘated. There is no evidence for an abrupt termination of all lineages at the F-F boundary, nor that the Atrypida were abundant at this time, since all groups were in decline and impoverished. Atypida were well established in dysaerobic, muddy substrate, reef lagoonal and off-reef deeper water settings in the late Givetian and Frasnian, alongside a range of brachiopod orders which sailed through the F-F boundary: tropical shelf anoxia or hypońa seems implausible as a cause for aĘpid extinction. Glacial-interglacial climate cycles recorded in South Ameńca for the Late Devonian, and their synchronous global cooling effect in low latitudes, as well as loss of the reef habitat and shelf area reduction, remain as the most likely combined scenarios for the mass extinction events. -

Upper Devonian Depositional and Biotic Events in Western New York

MIDDLE- UPPER DEVONIAN DEPOSITIONAL AND BIOTIC EVENTS IN WESTERN NEW YORK Gordon C. Baird, Dept. of Geosciences, SUNY-Fredonia, Fredonia, NY 14063; D. Jeffrey Over, Dept. of Geological Sciences, SUNY-Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454; William T. Kirch gasser, Dept. of Geology, SUNY-Potsdam, Potsdam, NY 13676; Carlton E. Brett, Dept. of Geology, Univ. of Cincinnati, 500 Geology/Physics Bldg., Cincinnati, OH 45221 INTRODUCTION The Middle and Late Devonian succession in the Buffalo area includes numerous dark gray and black shale units recording dysoxic to near anoxic marine substrate conditions near the northern margin of the subsiding Appalachian foreland basin. Contrary to common perception, this basin was often not stagnant; evidence of current activity and episodic oxygenation events are characteristic of many units. In fact, lag deposits of detrital pyrite roofed by black shale, erosional runnels, and cross stratified deposits of tractional styliolinid grainstone present a counter intuitive image of episodic, moderate to high energy events within the basin. We will discuss current-generated features observed at field stops in the context of proposed models for their genesis, and we will also examine several key Late Devonian bioevents recorded in the Upper Devonian stratigraphic succession. In particular, two stops will showcase strata associated with key Late Devonian extinction events including the Frasnian-Famennian global crisis. Key discoveries made in the preparation of this field trip publication, not recorded in earlier literature, -

The Eifelian Givetian Boundary (Middle Devonian) at Tsakhir, Govi Altai Region, Southern Mongolia

23rd Annual Keck Symposium: 2010 Houston, Texas THE EIFELIAN GIVETIAN BOUNDARY (MIDDLE DEVONIAN) AT TSAKHIR, GOVI ALTAI REGION, SOUTHERN MONGOLIA NICHOLAS SULLIVAN State University of New York at Geneseo Faculty Advisor: D. Jeffrey Over INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE GEOLOGIC SETTING The Devonian System (418.1±3.0 – 365.7±2.7 Ma) Badarch et al. (2002) argued that Mongolia consists is subdivided into three epochs, Lower, Middle, and of numerous terranes that were accreted onto small Upper, which are further subdivided into seven stag- Precambrian cratonic blocks in the Hangay Region es. The Middle Devonian is subdivided into the Eif- during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic. The focus of elian (391.9±3.4 – 388.1±2.6 Ma) and the Givetian this investigation are strata in a region recognized (388.1±2.6 - 383.7±3.1 Ma; Kaufmann, 2006). The as part of one of these accretionary wedges, which stage boundary is defined by the first appearance is referred to as the Gobi Altai Terrane (Figure 1; Ba- of Polygnathus hemiansatus at the Eifelian-Givetian darch et al., 2002; Minjin and Soja, 2009a). Badarch Stage Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP), et al. (2002) characterized the Gobi Altai Terrane as which is a section at Jebel Mech Irdane in the Tifilalt a backarc basin, as evidenced by abundant volcano- of Morocco (Walliser et al. 1995). At some sections, clastic sedimentary rocks. The volcanics within the the appearance of the goniatite Maenioceras undu- Gobi Altai Terrane are believed to be derived from latum has been used as a proxy for the boundary a prehistoric island arc represented by the Mandalo- (Kutcher and Schmidt, 1958). -

(Late Devonian) Boundary Within the Foreknobs Formation, Maryland and West Virginia

The Frasnian-Famennian (Late Devonian) boundary within the Foreknobs Formation, Maryland and West Virginia GEORGE R. McGHEE, JR. Department of Geological Sciences, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York 14627 ABSTRACT The approximate position of the Frasnian-Famennian (Late De- vonian) boundary is determined within the Foreknobs Formation along the Allegheny Front in Maryland and West Virginia by utiliz- ing the time ranges of the articulate brachiopods Athryis angelica Hall, Cyrtospirifer sulcifer (Hall), and members of the Atrypidae. INTRODUCTION The age of strata previously called the "Chemung Formation" along the Allegheny Front in Maryland and West Virginia (Fig. 1) has been of interest to Devonian wokers for some time. Recent at- tempts to resolve this problem include the works of Dennison (1970, 1971) and Curry (1975). New paleontological contribu- tions to the resolution of time relations within the Greenland Gap Group ("Chemung Formation") are the object of this paper, which is an outgrowth of a much larger ecological analysis of Late Devo- nian benthic marine fauna as preserved in the central Appalachians (McGhee, 1975, 1976). STRATIGRAPHIC SETTING The following is a condensation and summary of the evolution of Upper Devonian stratigraphic nomenclatural usage in the study Figure 1. Location map of study area, showing positions of the mea- area; for a more complete and thorough discussion, the reader is sured sections used in this study (after Dennison, 1970). referred to Dennison (1970) and Kirchgessner (1973). The Chemung Formation was originally designated by James lower Cohocton Stage." Elsewhere, concerning the upper limit of Hall (1839) from Chemung Narrows in south-central New York. -

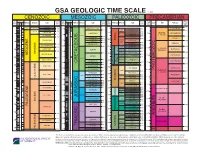

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

Early Carboniferous) Examensarbete Vid Institutionen För Geovetenskaper

The Tournaisian (Early Carboniferous) Examensarbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper Foraminifers From the Kuznetsk Basin ISSN 1650-6553 Nr 303 (South-West Siberia, Russia): Taxonomy, Biometry, Biostratigraphy Clémentine Colpaert The Tournaisian (Early Carboniferous) Foraminifers From the Kuznetsk Basin Revised Tournaisian foraminiferal assemblages of Kuznetsk Basin (Siberia, Russia) provide new accurate stratigraphic correlations for the Taidon and (South-West Siberia, Russia): Fominskoe formations, and palaeobiogeographic hypotheses for western Siberia. Microfacies analyses of Old Belovo Quarry, Artyshta village Section as well as Taxonomy, Biometry, Biostratigraphy Starobachaty village Section reveal four main types of wackestone or packstone with different skeletal grains, some foraminifers and very rare incertae sedis algae. The environments of deposit may be reconstructed as located in distal parts of inner ramps and proximal parts of mid ramp. If the unilocular foraminifer are relatively abundant in all the microfacies, the plurilocular ones occur only in bioclastic neomicrosparitized wackestone deposited in the shallower parts of the carbonate ramp. As the Tournaisian inner ramp is narrow, and only preserved in the Old Belovo Quarry, the Taidon and Fominskoe formations yield quite rare plurilocular Clémentine Colpaert foraminifers. They belong mainly to the superfamily Septabrunsiinoidea, and more precisely to the genera Septabrunsiina and Pseudoplanoendothyra. Rarer Granuliferella and Endothyra are sporadically present. The presence of Granuliferella and some “Devonian” Lazarus-genera allow to correlate the Taidon Formation with the MFZ3 to MFZ5 biozones defined in the Belgian stratotypes, and its top, with Endothyra, to the biozones MFZ5 and/or MFZ6. The Fominskoe Formation, overlain by series previously dated as earliest Viséan, corresponds to the whole late Tournaisian (MFZ6-MFZ8). -

Paleogeographic Maps Earth History

History of the Earth Age AGE Eon Era Period Period Epoch Stage Paleogeographic Maps Earth History (Ma) Era (Ma) Holocene Neogene Quaternary* Pleistocene Calabrian/Gelasian Piacenzian 2.6 Cenozoic Pliocene Zanclean Paleogene Messinian 5.3 L Tortonian 100 Cretaceous Serravallian Miocene M Langhian E Burdigalian Jurassic Neogene Aquitanian 200 23 L Chattian Triassic Oligocene E Rupelian Permian 34 Early Neogene 300 L Priabonian Bartonian Carboniferous Cenozoic M Eocene Lutetian 400 Phanerozoic Devonian E Ypresian Silurian Paleogene L Thanetian 56 PaleozoicOrdovician Mesozoic Paleocene M Selandian 500 E Danian Cambrian 66 Maastrichtian Ediacaran 600 Campanian Late Santonian 700 Coniacian Turonian Cenomanian Late Cretaceous 100 800 Cryogenian Albian 900 Neoproterozoic Tonian Cretaceous Aptian Early 1000 Barremian Hauterivian Valanginian 1100 Stenian Berriasian 146 Tithonian Early Cretaceous 1200 Late Kimmeridgian Oxfordian 161 Callovian Mesozoic 1300 Ectasian Bathonian Middle Bajocian Aalenian 176 1400 Toarcian Jurassic Mesoproterozoic Early Pliensbachian 1500 Sinemurian Hettangian Calymmian 200 Rhaetian 1600 Proterozoic Norian Late 1700 Statherian Carnian 228 1800 Ladinian Late Triassic Triassic Middle Anisian 1900 245 Olenekian Orosirian Early Induan Changhsingian 251 2000 Lopingian Wuchiapingian 260 Capitanian Guadalupian Wordian/Roadian 2100 271 Kungurian Paleoproterozoic Rhyacian Artinskian 2200 Permian Cisuralian Sakmarian Middle Permian 2300 Asselian 299 Late Gzhelian Kasimovian 2400 Siderian Middle Moscovian Penn- sylvanian Early Bashkirian -

2009 Geologic Time Scale Cenozoic Mesozoic Paleozoic Precambrian Magnetic Magnetic Bdy

2009 GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST. HIST. ANOM. ANOM. (Ma) CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 65.5 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 542 CALABRIAN MAASTRICHTIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE 1.8 31 C31 251 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 70.6 254 2A PIACENZIAN 32 C32 L 630 C2A 3.6 WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN 33 CAMPANIAN CAPITANIAN 5 C3 5.3 266 750 NEOPRO- CRYOGENIAN 80 C33 M WORDIAN MESSINIAN LATE 268 TEROZOIC 3A C3A 83.5 ROADIAN 7.2 SANTONIAN 271 85.8 KUNGURIAN 850 4 276 C4 CONIACIAN 280 4A 89.3 ARTINSKIAN TONIAN C4A L TORTONIAN 90 284 TURONIAN PERMIAN 10 5 93.5 E 1000 1000 C5 SAKMARIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 297 99.6 ASSELIAN STENIAN SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 299.0 5A 100 300 GZELIAN C5A 13.8 M KASIMOVIAN 304 1200 PENNSYL- 306 1250 15 5B LANGHIAN ALBIAN MOSCOVIAN MESOPRO- C5B VANIAN 312 ECTASIAN 5C 16.0 110 BASHKIRIAN TEROZOIC C5C 112 5D C5D MIOCENE 320 318 1400 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 326 6 C6 APTIAN 20 120 1500 CALYMMIAN E 20.4 6A C6A EARLY MISSIS- M0r 125 VISEAN 1600 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 SIPPIAN M3 BARREMIAN C6C 23.0 345 6C CRETACEOUS 130 M5 130 STATHERIAN CARBONIFEROUS TOURNAISIAN 7 C7 HAUTERIVIAN 1750 25 7A M10 C7A 136 359 8 C8 L CHATTIAN M12 VALANGINIAN 360 L 1800 140 M14 140 9 C9 M16 FAMENNIAN BERRIASIAN M18 PROTEROZOIC OROSIRIAN 10 C10 28.4 145.5 M20 2000 30 11 C11 TITHONIAN 374 PALEOPRO- 150 M22 2050 12 E RUPELIAN -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Page numbers in italic denote Figures. Page numbers in bold denote Tables. Acadian Orogeny 224 Ancyrodelloides delta biozone 15 Acanthopyge Limestone 126, 128 Ancyrodelloides transitans biozone 15, 17,19 Acastella 52, 68, 69, 70 Ancyrodelloides trigonicus biozone 15, 17,19 Acastoides 52, 54 Ancyrospora 31, 32,37 Acinosporites lindlarensis 27, 30, 32, 35, 147 Anetoceras 82 Acrimeroceras 302, 313 ?Aneurospora 33 acritarchs Aneurospora minuta 148 Appalachian Basin 143, 145, 146, 147, 148–149 Angochitina 32, 36, 141, 142, 146, 147 extinction 395 annulata Events 1, 2, 291–344 Falkand Islands 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 37 comparison of conodonts 327–331 late Devonian–Mississippian 443 effects on fauna 292–293 Prague Basin 137 global recognition 294–299, 343 see also Umbellasphaeridium saharicum limestone beds 3, 246, 291–292, 301, 308, 309, Acrospirifer 46, 51, 52, 73, 82 311, 321 Acrospirifer eckfeldensis 58, 59, 81, 82 conodonts 329, 331 Acrospirifer primaevus 58, 63, 72, 74–77, 81, 82 Tafilalt fauna 59, 63, 72, 74, 76, 103 ammonoid succession 302–305, 310–311 Actinodesma 52 comparison of facies 319, 321, 323, 325, 327 Actinosporites 135 conodont zonation 299–302, 310–311, 320 Acuticryphops 253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 264 Anoplia theorassensis 86 Acutimitoceras 369, 392 anoxia 2, 3–4, 171, 191–192, 191 Acutimitoceras (Stockumites) 357, 359, 366, 367, 368, Hangenberg Crisis 391, 392, 394, 401–402, 369, 372, 413 414–417, 456 agnathans 65, 71, 72, 273–286 and carbon cycle 410–413 Ahbach Formation 172 Kellwasser Events 237–239, 243, 245, 252 -

Conodont Biofacies in a Ramp to Basin Setting (Latest Devonian and Earliest Carboniferous) in the Rocky Mountains of Southernmost Canada and Northern Montana

U. S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Conodont biofacies in a ramp to basin setting (latest Devonian and earliest Carboniferous) in the Rocky Mountains of southernmost Canada and northern Montana by Lauret E. Savoy1 and Anita G. Harris 2 Open-File Report 93-184 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. \ Department of Geology and Geography, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, MA 01075 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA 22092 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 LITHOSTRATIGRAPHY AND DEPOSITIONAL SETTING 2 CONODONT BIOSTRATIGRAPHY AND BIOFACIES 8 Palliser Formation 8 Exshaw Formation 13 Banff Formation 13 Correlative units in the Lussier syncline 15 PALEOGEOGRAPfflC SETTING 17 CONCLUSION 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 23 REFERENCES CITED 24 APPENDIX 1 38 FIGURES 1. Index map of sections examined and major structural features of the thrust and fold belt 3 2. Correlation chart of Upper Devonian and Lower Mississippian stratigraphic units. 4 3. Selected microfacies of the Palliser Formation. 5 4. Type section of Exshaw Formation, Jura Creek. 6 5. Lower part of Banff Formation, North Lost Creek. 7 6. Conodont distribution in Palliser and Exshaw formations, Inverted Ridge. 9 7. Conodont distribution in upper Palliser and lower Banff formations, Crowsnest Pass. 11 8. Conodont distribution in upper Palliser, Exshaw, and lower Banff formations, composite Jura Creek - Mount Buller section. 12 9.