Ichnological Record of the Frasnian–Famennian Boundary Interval: Two Examples from the Holy Cross Mts (Central Poland)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extent and Duration of Marine Anoxia During the Frasnian– Famennian (Late Devonian) Mass Extinction in Poland, Germany, Austria and France

This is a repository copy of Extent and duration of marine anoxia during the Frasnian– Famennian (Late Devonian) mass extinction in Poland, Germany, Austria and France. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/297/ Article: Bond, D.P.G., Wignall, P.B. and Racki, G. (2004) Extent and duration of marine anoxia during the Frasnian– Famennian (Late Devonian) mass extinction in Poland, Germany, Austria and France. Geological Magazine, 141 (2). pp. 173-193. ISSN 0016-7568 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756804008866 Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Geol. Mag. 141 (2), 2004, pp. 173–193. c 2004 Cambridge University Press 173 DOI: 10.1017/S0016756804008866 Printed in the United Kingdom Extent and duration of marine anoxia during the Frasnian– Famennian (Late Devonian) mass extinction in Poland, Germany, Austria and France DAVID BOND*, PAUL B. WIGNALL*† & GRZEGORZ RACKI‡ *School of Earth Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK ‡Department of Palaeontology and Stratigraphy, University of Silesia, ul. Bedzinska 60, PL-41-200 Sosnowiec, Poland (Received 25 March 2003; accepted 10 November 2003) Abstract – The intensity and extent of anoxia during the two Kellwasser anoxic events has been investigated in a range of European localities using a multidisciplinary approach (pyrite framboid assay, gamma-ray spectrometry and sediment fabric analysis). -

Climate Instability and Tipping Points in the Late Devonian

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository – http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ Sarah K. Carmichael, Johnny A. Waters, Cameron J. Batchelor, Drew M. Coleman, Thomas J. Suttner, Erika Kido, L.M. Moore, and Leona Chadimová, (2015) Climate instability and tipping points in the Late Devonian: Detection of the Hangenberg Event in an open oceanic island arc in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, Gondwana Research The copy of record is available from Elsevier (18 March 2015), ISSN 1342-937X, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2015.02.009. Climate instability and tipping points in the Late Devonian: Detection of the Hangenberg Event in an open oceanic island arc in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt Sarah K. Carmichael a,*, Johnny A. Waters a, Cameron J. Batchelor a, Drew M. Coleman b, Thomas J. Suttner c, Erika Kido c, L. McCain Moore a, and Leona Chadimová d Article history: a Department of Geology, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608, USA Received 31 October 2014 b Department of Geological Sciences, University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, Received in revised form 6 Feb 2015 Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3315, USA Accepted 13 February 2015 Handling Editor: W.J. Xiao c Karl-Franzens-University of Graz, Institute for Earth Sciences (Geology & Paleontology), Heinrichstrasse 26, A-8010 Graz, Austria Keywords: d Institute of Geology ASCR, v.v.i., Rozvojova 269, 165 00 Prague 6, Czech Republic Devonian–Carboniferous Chemostratigraphy Central Asian Orogenic Belt * Corresponding author at: ASU Box 32067, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608, USA. West Junggar Tel.: +1 828 262 8471. E-mail address: [email protected] (S.K. -

Cretaceous–Paleogene Extinction Event (End Cretaceous, K-T Extinction, Or K-Pg Extinction): 66 MYA At

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (End Cretaceous, K-T extinction, or K-Pg extinction): 66 MYA at • About 17% of all families, 50% of all genera and 75% of all species became extinct. • In the seas it reduced the percentage of sessile animals to about 33%. • All non-avian dinosaurs became extinct during that time. • Iridium anomaly in sediments may indicate comet or asteroid induced extinctions Triassic–Jurassic extinction event (End Triassic): 200 Ma at the Triassic- Jurassic transition. • About 23% of all families, 48% of all genera (20% of marine families and 55% of marine genera) and 70-75% of all species went extinct. • Most non-dinosaurian archosaurs, most therapsids, and most of the large amphibians were eliminated • Dinosaurs had with little terrestrial competition in the Jurassic that followed. • Non-dinosaurian archosaurs continued to dominate aquatic environments • Theories on cause: 1.) Gradual climate change, perhaps with ocean acidification has been implicated, but not proven. 2.) Asteroid impact has been postulated but no site or evidence has been found. 3.) Massive volcanics, flood basalts and continental margin volcanoes might have damaged the atmosphere and warmed the planet. Permian–Triassic extinction event (End Permian): 251 Ma at the Permian-Triassic transition. Known as “The Great Dying” • Earth's largest extinction killed 57% of all families, 83% of all genera and 90% to 96% of all species (53% of marine families, 84% of marine genera, about 96% of all marine species and an estimated 70% of land species, • The evidence of plants is less clear, but new taxa became dominant after the extinction. -

Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian Mass Extinction: Comparing Brachiopod Faunas

Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian mass extinction: Comparing brachiopod faunas PAUL COPPER Copper, P. 1998. Evaluating the Frasnian-Famennian mass extinction: Comparing bra- chiopod faunas.- Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 43,2,137-154. The Frasnian-Famennian (F-F) mass extinctions saw the global loss of all genera belonging to the tropically confined order Atrypida (and Pentamerida): though Famen- nian forms have been reported in the literafure, none can be confirmed. Losses were more severe during the Givetian (including the extinction of the suborder Davidsoniidina, and the reduction of the suborder Lissatrypidina to a single genus),but ońgination rates in the remaining suborder surviving into the Frasnian kept the group alive, though much reduced in biodiversity from the late Earb and Middle Devonian. In the terminal phases of the late Palmatolepis rhenana and P linguifurmis zones at the end of the Frasnian, during which the last few Atrypidae dechned, no new genera originated, and thus the Atrypida were extĘated. There is no evidence for an abrupt termination of all lineages at the F-F boundary, nor that the Atrypida were abundant at this time, since all groups were in decline and impoverished. Atypida were well established in dysaerobic, muddy substrate, reef lagoonal and off-reef deeper water settings in the late Givetian and Frasnian, alongside a range of brachiopod orders which sailed through the F-F boundary: tropical shelf anoxia or hypońa seems implausible as a cause for aĘpid extinction. Glacial-interglacial climate cycles recorded in South Ameńca for the Late Devonian, and their synchronous global cooling effect in low latitudes, as well as loss of the reef habitat and shelf area reduction, remain as the most likely combined scenarios for the mass extinction events. -

Upper Devonian Depositional and Biotic Events in Western New York

MIDDLE- UPPER DEVONIAN DEPOSITIONAL AND BIOTIC EVENTS IN WESTERN NEW YORK Gordon C. Baird, Dept. of Geosciences, SUNY-Fredonia, Fredonia, NY 14063; D. Jeffrey Over, Dept. of Geological Sciences, SUNY-Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454; William T. Kirch gasser, Dept. of Geology, SUNY-Potsdam, Potsdam, NY 13676; Carlton E. Brett, Dept. of Geology, Univ. of Cincinnati, 500 Geology/Physics Bldg., Cincinnati, OH 45221 INTRODUCTION The Middle and Late Devonian succession in the Buffalo area includes numerous dark gray and black shale units recording dysoxic to near anoxic marine substrate conditions near the northern margin of the subsiding Appalachian foreland basin. Contrary to common perception, this basin was often not stagnant; evidence of current activity and episodic oxygenation events are characteristic of many units. In fact, lag deposits of detrital pyrite roofed by black shale, erosional runnels, and cross stratified deposits of tractional styliolinid grainstone present a counter intuitive image of episodic, moderate to high energy events within the basin. We will discuss current-generated features observed at field stops in the context of proposed models for their genesis, and we will also examine several key Late Devonian bioevents recorded in the Upper Devonian stratigraphic succession. In particular, two stops will showcase strata associated with key Late Devonian extinction events including the Frasnian-Famennian global crisis. Key discoveries made in the preparation of this field trip publication, not recorded in earlier literature, -

(Late Devonian) Boundary Within the Foreknobs Formation, Maryland and West Virginia

The Frasnian-Famennian (Late Devonian) boundary within the Foreknobs Formation, Maryland and West Virginia GEORGE R. McGHEE, JR. Department of Geological Sciences, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York 14627 ABSTRACT The approximate position of the Frasnian-Famennian (Late De- vonian) boundary is determined within the Foreknobs Formation along the Allegheny Front in Maryland and West Virginia by utiliz- ing the time ranges of the articulate brachiopods Athryis angelica Hall, Cyrtospirifer sulcifer (Hall), and members of the Atrypidae. INTRODUCTION The age of strata previously called the "Chemung Formation" along the Allegheny Front in Maryland and West Virginia (Fig. 1) has been of interest to Devonian wokers for some time. Recent at- tempts to resolve this problem include the works of Dennison (1970, 1971) and Curry (1975). New paleontological contribu- tions to the resolution of time relations within the Greenland Gap Group ("Chemung Formation") are the object of this paper, which is an outgrowth of a much larger ecological analysis of Late Devo- nian benthic marine fauna as preserved in the central Appalachians (McGhee, 1975, 1976). STRATIGRAPHIC SETTING The following is a condensation and summary of the evolution of Upper Devonian stratigraphic nomenclatural usage in the study Figure 1. Location map of study area, showing positions of the mea- area; for a more complete and thorough discussion, the reader is sured sections used in this study (after Dennison, 1970). referred to Dennison (1970) and Kirchgessner (1973). The Chemung Formation was originally designated by James lower Cohocton Stage." Elsewhere, concerning the upper limit of Hall (1839) from Chemung Narrows in south-central New York. -

Precisely Dating the Frasnian–Famennian Boundary

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Precisely dating the Frasnian– Famennian boundary: implications for the cause of the Late Devonian Received: 12 April 2018 Accepted: 12 June 2018 mass extinction Published: xx xx xxxx L. M. E. Percival1, J. H. F. L. Davies2, U. Schaltegger 2, D. De Vleeschouwer3, A.-C. Da Silva4,5 & K. B. Föllmi1 The Frasnian–Famennian boundary records one of the most catastrophic mass extinctions of the Phanerozoic Eon. Several possible causes for this extinction have been suggested, including extra- terrestrial impacts and large-scale volcanism. However, linking the extinction with these potential causes is hindered by the lack of precise dating of either the extinction or volcanic/impact events. In this study, a bentonite layer in uppermost-Frasnian sediments from Steinbruch Schmidt (Germany) is re-analysed using CA-ID-TIMS U-Pb zircon geochronology in order to constrain the date of the Frasnian–Famennian extinction. A new age of 372.36 ± 0.053 Ma is determined for this bentonite, confrming a date no older than 372.4 Ma for the Frasnian–Famennian boundary, which can be further constrained to 371.93–371.78 Ma using a pre-existing Late Devonian age model. This age is consistent with previous dates, but is signifcantly more precise. When compared with published ages of the Siljan impact crater and basalts produced by large-scale volcanism, there is no apparent correlation between the extinction and either phenomenon, not clearly supporting them as a direct cause for the Frasnian– Famennian event. This result highlights an urgent need for further Late Devonian geochronological and chemostratigraphic work to better understand the cause(s) of this extinction. -

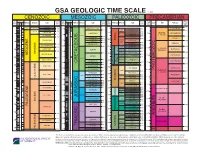

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

The Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

P1: FXY/GBP P2: aaa February 24, 2001 19:23 Annual Reviews AR125-12 Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2001. 29:331–64 Copyright c 2001 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved THE LATE ORDOVICIAN MASS EXTINCTION Peter M Sheehan Department of Geology, Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53233; e-mail: [email protected] Key Words extinction event, Silurian, glaciation, evolutionary recovery, ecologic evolutionary unit ■ Abstract Near the end of the Late Ordovician, in the first of five mass extinctions in the Phanerozoic, about 85% of marine species died. The cause was a brief glacial interval that produced two pulses of extinction. The first pulse was at the beginning of the glaciation, when sea-level decline drained epicontinental seaways, produced a harsh climate in low and mid-latitudes, and initiated active, deep-oceanic currents that aerated the deep oceans and brought nutrients and possibly toxic material up from oceanic depths. Following that initial pulse of extinction, surviving faunas adapted to the new ecologic setting. The glaciation ended suddenly, and as sea level rose, the climate moderated, and oceanic circulation stagnated, another pulse of extinction occurred. The second extinction marked the end of a long interval of ecologic stasis (an Ecologic-Evolutionary Unit). Recovery from the event took several million years, but the resulting fauna had ecologic patterns similar to the fauna that had become extinct. Other extinction events that eliminated similar or even smaller percentages of species had greater long-term ecologic effects. INTRODUCTION The Late Ordovician extinction was the first of five great extinction events of the by Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico on 03/15/13. -

Early Carboniferous) Examensarbete Vid Institutionen För Geovetenskaper

The Tournaisian (Early Carboniferous) Examensarbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper Foraminifers From the Kuznetsk Basin ISSN 1650-6553 Nr 303 (South-West Siberia, Russia): Taxonomy, Biometry, Biostratigraphy Clémentine Colpaert The Tournaisian (Early Carboniferous) Foraminifers From the Kuznetsk Basin Revised Tournaisian foraminiferal assemblages of Kuznetsk Basin (Siberia, Russia) provide new accurate stratigraphic correlations for the Taidon and (South-West Siberia, Russia): Fominskoe formations, and palaeobiogeographic hypotheses for western Siberia. Microfacies analyses of Old Belovo Quarry, Artyshta village Section as well as Taxonomy, Biometry, Biostratigraphy Starobachaty village Section reveal four main types of wackestone or packstone with different skeletal grains, some foraminifers and very rare incertae sedis algae. The environments of deposit may be reconstructed as located in distal parts of inner ramps and proximal parts of mid ramp. If the unilocular foraminifer are relatively abundant in all the microfacies, the plurilocular ones occur only in bioclastic neomicrosparitized wackestone deposited in the shallower parts of the carbonate ramp. As the Tournaisian inner ramp is narrow, and only preserved in the Old Belovo Quarry, the Taidon and Fominskoe formations yield quite rare plurilocular Clémentine Colpaert foraminifers. They belong mainly to the superfamily Septabrunsiinoidea, and more precisely to the genera Septabrunsiina and Pseudoplanoendothyra. Rarer Granuliferella and Endothyra are sporadically present. The presence of Granuliferella and some “Devonian” Lazarus-genera allow to correlate the Taidon Formation with the MFZ3 to MFZ5 biozones defined in the Belgian stratotypes, and its top, with Endothyra, to the biozones MFZ5 and/or MFZ6. The Fominskoe Formation, overlain by series previously dated as earliest Viséan, corresponds to the whole late Tournaisian (MFZ6-MFZ8). -

Life and Global Climate Change on Earth

Journal of Sustainability Studies Volume 1 Issue 1 What is Sustainability Article 7 February 2018 Life and Global Climate Change on Earth Mark Puckett Ph.D. University of North Alabama Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.una.edu/sustainabilityjournal Part of the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Puckett, M. (2018). Life and Global Climate Change on Earth. Journal of Sustainability Studies, 1 (1). Retrieved from https://ir.una.edu/sustainabilityjournal/vol1/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNA Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Sustainability Studies by an authorized editor of UNA Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Puckett: Life and Global Climate Change on Earth Life and Global Climate Change on Earth By Mark Puckett, Ph.D. Professor of Geology, Dept. of Physics and Earth Science, University of North Alabama Introduction The history of life on Planet Earth, fueled by the solar radiation in which it has bathed throughout the eons of geologic time, records great periods of richness and the evolutionary appearance of an incredible diversity of life forms, punctuated by short intervals of wholesale destruction and partial collapses of the biosphere. Many of these destructive events are related to carbon and its exchange between reservoirs in the ground, (magmatic sources and from the shallow burial of organic matter that is life’s debris) and in the atmosphere and oceans. This scenario is happening today as the combined effects of the human burning of fossil fuels is transferring bulk amounts of carbon from the earth into the atmosphere. -

Paleogeographic Maps Earth History

History of the Earth Age AGE Eon Era Period Period Epoch Stage Paleogeographic Maps Earth History (Ma) Era (Ma) Holocene Neogene Quaternary* Pleistocene Calabrian/Gelasian Piacenzian 2.6 Cenozoic Pliocene Zanclean Paleogene Messinian 5.3 L Tortonian 100 Cretaceous Serravallian Miocene M Langhian E Burdigalian Jurassic Neogene Aquitanian 200 23 L Chattian Triassic Oligocene E Rupelian Permian 34 Early Neogene 300 L Priabonian Bartonian Carboniferous Cenozoic M Eocene Lutetian 400 Phanerozoic Devonian E Ypresian Silurian Paleogene L Thanetian 56 PaleozoicOrdovician Mesozoic Paleocene M Selandian 500 E Danian Cambrian 66 Maastrichtian Ediacaran 600 Campanian Late Santonian 700 Coniacian Turonian Cenomanian Late Cretaceous 100 800 Cryogenian Albian 900 Neoproterozoic Tonian Cretaceous Aptian Early 1000 Barremian Hauterivian Valanginian 1100 Stenian Berriasian 146 Tithonian Early Cretaceous 1200 Late Kimmeridgian Oxfordian 161 Callovian Mesozoic 1300 Ectasian Bathonian Middle Bajocian Aalenian 176 1400 Toarcian Jurassic Mesoproterozoic Early Pliensbachian 1500 Sinemurian Hettangian Calymmian 200 Rhaetian 1600 Proterozoic Norian Late 1700 Statherian Carnian 228 1800 Ladinian Late Triassic Triassic Middle Anisian 1900 245 Olenekian Orosirian Early Induan Changhsingian 251 2000 Lopingian Wuchiapingian 260 Capitanian Guadalupian Wordian/Roadian 2100 271 Kungurian Paleoproterozoic Rhyacian Artinskian 2200 Permian Cisuralian Sakmarian Middle Permian 2300 Asselian 299 Late Gzhelian Kasimovian 2400 Siderian Middle Moscovian Penn- sylvanian Early Bashkirian