Analyzing Hip Hop Discourse As a Locus of 'Men's Language'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cowl Island/Page 19 Vol

BACK PAGE: Focus on student health Deanna Cioppa '07 Men's hoops win Think twice before going tanning for spring Are you getting enough sleep? Experts say reviews Trinity over West Virginia, break ... and get a free Dermascan in Ray extra naps could save your heart Hear Repertory Theater's bring Friars back Cafeteria this coming week/Page 4 from the PC health center/Page 8 latest, A Delicate into the running for Balance/Page 15 NCAA bid Est. 1935 Sarah Amini '07 Men's and reminisces about women’s track win riding the RIPTA big at Big East 'round Rhose Championships The Cowl Island/Page 19 Vol. LXXI No. 18 www.TheCowl.com • Providence College • Providence, R.I. February 22, 2007 Protesters refuse to be silenced by Jennifer Jarvis ’07 News Editor s the mild weather cooled off at sunset yesterday, more than 100 students with red shirts and bal loons gathered at the front gates Aof Providence College, armed with signs saying “We will not stop fighting for an end to sexual assault,” and “Vaginas are not vulgar, rape is vulgar.” For the second year in a row, PC students protested the decision of Rev. Brian J. Shanley, O.P., president of Providence College, to ban the production of The Vagina Monologues on 'campus. Many who saw a similar protest one year ago are asking, is this deja vu? Perhaps, but the cast and crew of The Vagina Monologues and many other sup porters said they will not stop protesting just because the production was banned last year. -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed. -

Sonic Jihadâ•Flmuslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration

FIU Law Review Volume 11 Number 1 Article 15 Fall 2015 Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/lawreview Part of the Other Law Commons Online ISSN: 2643-7759 Recommended Citation SpearIt, Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration, 11 FIU L. Rev. 201 (2015). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.25148/lawrev.11.1.15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Law Review by an authorized editor of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 37792-fiu_11-1 Sheet No. 104 Side A 04/28/2016 10:11:02 12 - SPEARIT_FINAL_4.25.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 4/25/16 9:00 PM Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt* I. PROLOGUE Sidelines of chairs neatly divide the center field and a large stage stands erect. At its center, there is a stately podium flanked by disciplined men wearing the militaristic suits of the Fruit of Islam, a visible security squad. This is Ford Field, usually known for housing the Detroit Lions football team, but on this occasion it plays host to a different gathering and sentiment. The seats are mostly full, both on the floor and in the stands, but if you look closely, you’ll find that this audience isn’t the standard sporting fare: the men are in smart suits, the women dress equally so, in long white dresses, gloves, and headscarves. -

The Post-Traumatic Futurities of Black Debility

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. Koivisto, Mikko (Live!) The Post-traumatic Futurities of Black Debility Published in: DISABILITY STUDIES QUARTERLY DOI: 10.18061/dsq.v39i3.6614 Published: 30/08/2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please cite the original version: Koivisto, M. (2019). (Live!) The Post-traumatic Futurities of Black Debility. DISABILITY STUDIES QUARTERLY, 39(3). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v39i3.6614 This material is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) (Live!) The Post-traumatic Futurities of Black Debility Mikko O. Koivisto Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture Email: [email protected] Keywords: Pharoahe Monch, debilitation, racism, ableism, sanism, rap music Abstract This article investigates the possibilities of artistic and performative strategies for elucidating forms of systemic violence targeted at racialized and disabled bodies. The analysis focuses on the album PTSD: Post traumatic stress disorder by the New York rapper Pharoahe Monch, delving into the ways in which it explores the intersections of Blackness and disability. The album's lyrics range from a critique of the structural racism in contemporary American society to subjective, embodied experiences of clinical depression, anxiety, and chronic asthma—and their complex entanglement. -

LITTLE BROTHER the Listening

LITTLE BROTHER The Listening KEY SELLING POINTS • White vinyl reissue • Includes bonus 7” DESCRIPTION ARTIST: Little Brother “In Little Brother’s music, the North Carolina group makes a specific TITLE: The Listening point to highlight the more refined aspects of mid-’90s hip-hop. CATALOG: l-ABB1038 Basing its 2002 sound upon the foundation previously established LABEL: ABB Records by the likes of Pete Rock, A Tribe Called Quest, Jay Dee, and Black GENRE: Hip-Hop/Rap Star, Little Brother makes somewhat of a political statement by BARCODE: N/A ABB1038 applying such standards to this modern age. The Listening does FORMAT: 2XLP + 7” an exceptional job of proving that soulful meditations have indeed RELEASE: 7/14/2017 retained their traditional relevancy within the contemporary realms LIST PRICE: $22.98 / CS of rap. 9th Wonder’s production leads the charge with distinct drum kicks pacing larger-than-life melodic samples, which are often TRACKLISTING enhanced with sultry female voice-overs. Meanwhile, Phonte and 1. Morning Big Pooh dig even deeper within the hip-hop vaults as they draw 2. For You upon classic routines by the likes of Rakim, Slick Rick, and Audio 2 3. Speed for their lyrical inspiration. 4. Whatever You Say 5. Make Me Hot Whether engaged in storytelling, braggadocio, or simple 6. The Yo-Yo reassurance, the rhyming duo complements 9th Wonder’s varying 7. Shorty on the Lookout 8. Love Joint Revisited shades of mood music with a consistent degree of skill and sincerity. 9. So Fabulous The album both starts and finishes strongly, with “For You,” “Speed,” 10. -

Neuhoff, Laura-Brynn.Pdf (929Kb)

“THE BIGGEST COLORED SHOW ON EARTH”: HOW MINSTRELSY HAS DEFINED PERFORMANCES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY FROM 19TH CENTURY THEATER TO HIP HOP A Senior Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies By Laura-Brynn Neuhoff Washington, D.C. April 26, 2017 “THE BIGGEST COLORED SHOW ONE EARTH”: HOW MINSTRELSY HAS DEFINED PERFORMANCES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY FROM 19TH CENTURY THEATER TO HIP HOP Laura-Brynn Neuhoff Thesis Adviser: Marcia Chatelain, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This senior thesis seeks to answer the following question: how and why is the word “minstrel” and associated images still used in American rap and hip hop performances? The question was sparked by the title of a 2005 rap album by the group Little Brother: The Minstrel Show. The record is packaged as a television variety show, complete with characters, skits, and references to blackface. This album premiered in the heat of the Minstrel Show Debate when questions of authenticity and representation in rap and hip hop engaged community members. My research is first historical: I analyze images of minstrelsy and reviews of minstrel shows from the 1840s into the twentieth century to understand how the racist images persisted and to unpack the ambiguity of the legacy of black blackface performers. I then analyze the rap scene from the late 2000-2005, when the genre most poignantly faced the identity crisis spurred by those referred to as “minstrel” performers. Having conducted interviews with the two lyricists of Little Brother: Rapper Big Pooh and Phonte, I primarily use Little Brother as my center of research, analyzing their production in conjunction with their spatial position in the hip hop community. -

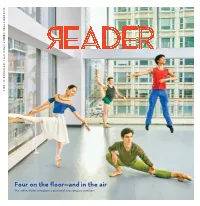

Four on the Floor—And in The

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | SEPTEMBER | SEPTEMBER CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Four on the fl oor—and in the air The Joff rey Ballet introduces a quartet of new company members. THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | SEPTEMBER | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE T R - CITYLIFE King’sSpeechlooksgoodbutthe city’srappersbutitservesasa @ 03 FeralCitizenAnexcerptfrom dramaisinertatChicagoShakes vitalincubatorforadventurous NanceKlehm’sTheSoilKeepers 18 PlaysofnoteOsloilluminates ambitiousinstrumentalhiphop thebehindthescenes 29 ShowsofnoteHydeParkJazz PTB machinationsofMiddleEast FestNickCaveFireToolzand ECSKKH DEKS diplomacyHelloAgainoff ersa morethisweek CLSK daisychainoflustyinterludes 32 TheSecretHistoryof D P JR ChicagoMusicLittleknown M EP M TD KR FEATURE FILM bluesrockwizardZachPratherhas A EJL 08 JuvenileLiferInmore 21 ReviewRickAlverson’sThe foundhiscrowdinEurope S MEBW thanadultswhoweresent Mountainisafascinatingbut 34 EarlyWarningsCalexicoPile SWDI BJ MS askidstodieinprisonweregivena ultimatelyfrustratingmoodpiece TierraWhackandmorejust SWMD L G secondchanceMarshanAllenwas 22 MoviesofnoteTheCat announcedconcerts EA SN L oneofthem Rescuersdocumentstheheroic 34 GossipWolfGrünWasser L CS C -J F L CPF actsofBrooklyncatpeopleMisty diversifytheirapocalypticEBMon D A A FOOD&DRINK ARTS&CULTURE Buttonisbrimmingwithwitty NotOKWithThingstheChicago CN B 05 RestaurantReviewDimsum 12 LitEverythingMustGopays dialogueandcolorfulcharacters SouthSideFilmFestivalcelebrates LCIG M H JH andwinsomeatLincolnPark’sD tributetoWickerPark’sdisplaced -

"What Is an MC If He Can't Rap?"

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2019 "What Is An MC If He Can't Rap?" Dominique Jimmerson California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Jimmerson, Dominique, ""What Is An MC If He Can't Rap?"" (2019). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 569. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/569 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dominique Jimmerson Capstone Sammons 5-18 -19 “What Is an MC if He Can’t Rap?” Hip hop is a genre that has seen much attention in mainstream media in recent years. It is becoming one of the most dominant genres in the world and influencing popular culture more and more as the years go on. One of the main things that makes hip hop unique from other genres is the emphasis on the lyricist. While many other genres will have a drummer, guitarist, bassist, or keyboardist, hip hop is different because most songs are not crafted in the traditional way of a band putting music together. Because of this, the genre tends to focus on the lyrics. -

The Symbolic Rape of Representation: a Rhetorical Analysis of Black Musical Expression on Billboard's Hot 100 Charts

THE SYMBOLIC RAPE OF REPRESENTATION: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF BLACK MUSICAL EXPRESSION ON BILLBOARD'S HOT 100 CHARTS Richard Sheldon Koonce A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Committee: John Makay, Advisor William Coggin Graduate Faculty Representative Lynda Dee Dixon Radhika Gajjala ii ABSTRACT John J. Makay, Advisor The purpose of this study is to use rhetorical criticism as a means of examining how Blacks are depicted in the lyrics of popular songs, particularly hip-hop music. This study provides a rhetorical analysis of 40 popular songs on Billboard’s Hot 100 Singles Charts from 1999 to 2006. The songs were selected from the Billboard charts, which were accessible to me as a paid subscriber of Napster. The rhetorical analysis of these songs will be bolstered through the use of Black feminist/critical theories. This study will extend previous research regarding the rhetoric of song. It also will identify some of the shared themes in music produced by Blacks, particularly the genre commonly referred to as hip-hop music. This analysis builds upon the idea that the majority of hip-hop music produced and performed by Black recording artists reinforces racial stereotypes, and thus, hegemony. The study supports the concept of which bell hooks (1981) frequently refers to as white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and what Hill-Collins (2000) refers to as the hegemonic domain. The analysis also provides a framework for analyzing the themes of popular songs across genres. The genres ultimately are viewed through the gaze of race and gender because Black male recording artists perform the majority of hip-hop songs. -

Hip Hop and Literacy in the Lives of Two Students in a Transitional English Course

Running head: HIP HOP AND LITERACY 1 Hip hop and Literacy in the Lives of Two Students in a Transitional English Course A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) in the College of Education, Criminal Justice and Human Services Literacy and Second Language Studies University of Cincinnati Deborah M. Sánchez, M.Ed. Dr. Susan Watts-Taffe (Chair) Dr. Chester Laine (Co-chair) Dr. Carmen Kynard (Member) Dr. Gulbahar Beckett (Member) HIP HOP AND LITERACY 2 Abstract This qualitative dissertation study investigated the following research question: How does Hip hop influence the literate lives, i.e., the connections of Hip hop to readings, writings and other communicative practices, of students who placed into transitional college English courses? The impetus for the study came from the importance that Hip hop has in the lives of young people (Smitherman, 1997). The participants in this study, Dionne and Mike, were students placed into a 1st year non-credit bearing English course, also known as a transitional course (Armstrong, 2007), at a 4-year university. The study employed tools of ethnography (Heath & Street, 2008), such as interviews, classroom observations and textual analysis of students‘ language and literacy practices in spaces inside and outside of the classroom. This study is conceptually framed within cultural studies (Hicks, 2003, 2005, 2009; Nelson, Treichler, & Grossberg, 1992) and sociocultural studies (Dyson & Smitherman, 2009; Street, 2001). Data were analyzed using linguistic analysis (Alim, 2006) and textual analysis (Kellner, 2009). -

Table Des Matières

TABLE DES MATIÈRES 7 INTRODUCTION 42 SPOONIE GEE « SPOONIN RAP » CLOUD ONE « PATTY DUKE » 44 AFRIKA SAMBA AT A A « PLANET ROCK » HRAFTWERK «TRANS-EUROPE EXPRESS » 46 MALCOLM MCLAREN « BUFFALO GALS » KOOL & THE 6ANC « SUMMER MADNESS (LIVE) » 48 SCHOOLLY D « P.S.K.-WHAT DOES IT MEAN? » BESIDE « CHANGETHE BEAT (FEMALEVERSION) » 50 BEASTIE BOYS « RHYMIN' & STEALIN' » LED ZEPPELIN «WHENTHE LEVEE BREAKS » 52 MC SHAN «THE BRIDGE » THE HONEY DRIPPERS « IMPEACH THE PRESIDENT » 54 RUN-DMC « PETER PIPER » BOB JAMES «TAKE ME TO THE MARDI GRAS » 56 BOOGIE DOWN P. « SOUTH BRONX » JAMES BROWN « GET UP OFFA THAT THING » 58 COLDCIIT « BEATS + PIECES » EDDIE BO & THE SOUL F. «WE'RE DOING IT (THANG) PART II » 60 ERIC B. & RAKIM « PAID IN FULL » THE SOUL SEARCHERS « ASHLEY'S ROACHCLIP » 62 PUBLIC ENEMY « REBEL WITHOUT A PAUSE » JAMES BROWN « FUNKY DRUMMER » 64 THE 45 KING «THE 900 NUMBER » MARVA WHITNEY « UNWIND YOURSELF » 66 BIG DADDY KANE «AIN'T NO HALF-STEPPIN' » THE EMOTIONS « BLIND ALLEY » 68 NC HAMMER « TURN THIS MUTHA OUT » INCREDIBLE BONGO BAND «APACHE » 70 N.W.A « STRAIGHT OUTTA COMPTON » THE WINSTONS «AMEN, BROTHER » 72 ULTRAMAGNETIC MC'S « EGO TRIPPIN' » KELVIN BLISS « SYNTHETIC SUBSTITUTION » 74 DE LA SOUL « SAY NO GO » DARYL HALL & JOHN OATES « I CANT GO FOR THAT » 76 EPMD « THE BIG PAYBACK » JANES BROWN « BABY, HERE I COME » 78 KOOL G RAP & DJ P. « ROAD TO THE RICHES » BILLY JOEL « STILETTO » 80 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST « CAN I KICK IT? » LOU REED «WALK ON THE WILD SIDE » 82 ABOVE THE LAW « MURDER RAP » OVINCY JONES « IRONSIDE » 84 POOR RIGHTEOUS TEACHERS « SHAKIYLA » ZAPP « BE ALRIGHT» 86 X-CLAN « GRAND VERBALIZER, WHAT TIME IS IT? » FELA KUTI « SORROW TEARS AND BLOOD » 88 BIZ MARKIE «ALONEAGAIN » GILBERT O'SULLIVAN «ALONEAGAIN (NATURALLY) » 90 CYPRESS HILL « HOW I COULD JUST KILLA MAN » MANZEL « MIDNIGHT THEME » 92 GETO BOYS « MIND PLAYING TRICKS ON ME » ISSAC HAYES « HUNG UP ON MY BABY » 94 MAIN SOURCE « LIVE ATTHE BARBEQUE » VICKI ANDERSON « IN THE LAND OF MILK AND HONEY » 96 MC SOLAAR « QUI SÈME LEVENT RÉCOLTE..