Fetus Magic and Sorcery Fears in Roman Egypt David Frankfurter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magical Objects in Victorian Literature: Enchantment, Narrative Imagination, and the Power of Things

Magical Objects in Victorian Literature: Enchantment, Narrative Imagination, and the Power of Things By Dan Fang Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August, 2015 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Jay Clayton, Ph.D. Rachel Teukolsky, Ph.D. Jonathan Lamb, Ph.D. Carolyn Dever, Ph.D. Elaine Freedgood, Ph.D. For lao-ye, who taught me how to learn ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the Martha Rivers Ingram Fellowship, which funded my last year of dissertation writing. My thanks go to Mark Wollaeger, Dana Nelson, the English Department, and the Graduates School for the Fellowship and other generous grants. My ideas were shaped by each and every professor with whom I have ever taken a class—in particular, Jonathan Lamb who was a large part of the inception of a project about things and who remained an unending font of knowledge through its completion. I want to thank Carolyn Dever for making me reflect upon my writing process and my mental state, not just the words on the page, and Elaine Freedgood for being an amazingly generous reader who never gave up on pushing me to be more rigorous. Most of all, my gratitude goes to Rachel Teukolsky and Jay Clayton for being the best dissertation directors I could ever imagine having. Rachel has molded both my arguments and my prose from the very first piece on Aladdin’s lamp, in addition to providing thoughtful advice about the experience of being in graduate school and beyond. -

Magical Herbalism Pdf, Epub, Ebook

MAGICAL HERBALISM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott Cunningham | 260 pages | 08 Nov 2001 | Llewellyn Publications,U.S. | 9780875421209 | English | Minnesota, United States Magical Herbalism PDF Book Tend and care of the foxglove, also known as fairies thimbles, to enjoy their protection. Worn or carried, it ensures safety during travel. So, use aconite to wash your ritual tools and space. Nov 19, Natural magic utilizes the world around us for magical purposes. And most importantly, they work! This protection herb can be used in a sachet. Money, luck, healing, obtaining the treasure. Taken to funerals, eases grief and calms mind. Today the name Cunningham is synonymous with natural magic and the magical community. This is a popular Hoodoo charm for gamblers. Use to dress candles for any form of magickal healing. I'm an open-minded person, but I'm logical. Why are herbs magical? Smolder for purification. Any object which holds some caraway seeds is theft-free. Often used as a substitute for the rare mandrake root in poppet magick. Empower with tourmaline. Increases the power of any incense you make. A composition book or spiral bound notebook works perfectly! Magical Herbalism Writer Amaranth Amaranthus hydrochondriacus Love-lies-bleeding, red cockscomb, velvet flower Feminine. Out-of-Body Experiences. The question to ask is, How? Folk magick is accessible to everyone. A bag of camphor hung around the neck keeps flus and colds away. Use with caution. Burn as incense or carry as a sachet for a good psychic power stimulator. Bavarian Root Doctors and Herbal Lore. Corn Zea Mays aka maize, seed of seeds, sacred mother Feminine. -

Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: an Authoritative Edition

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 1-12-2005 Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative Edition Paul Melvin Wise Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Wise, Paul Melvin, "Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative Edition." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2005. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COTTON MATHER’S WONDERS OF THE INVISIBLE WORLD: AN AUTHORITATIVE EDITION by PAUL M. WISE Under the direction of Reiner Smolinski ABSTRACT In Wonders of the Invisible World, Cotton Mather applies both his views on witchcraft and his millennial calculations to events at Salem in 1692. Although this infamous treatise served as the official chronicle and apologia of the 1692 witch trials, and excerpts from Wonders of the Invisible World are widely anthologized, no annotated critical edition of the entire work has appeared since the nineteenth century. This present edition seeks to remedy this lacuna in modern scholarship, presenting Mather’s seventeenth-century text next to an integrated theory of the natural causes of the Salem witch panic. The likely causes of Salem’s bewitchment, viewed alongside Mather’s implausible explanations, expose his disingenuousness in writing about Salem. Chapter one of my introduction posits the probability that a group of conspirators, led by the Rev. -

Download Enchantment Is All About Us for FREE

In Enchantment is All About Us Beatrice Walditchreveals that much of the what we often think of a real in the modern world is an enchantment woven by profit-driven businesses and nefarious politicians. Drawing upon a wide range of traditional worldviews, she sets out ways of mentally ‘banishing’ such pervasive enchantments and empowering the reader to create their own enchantments. Many of the suggestions develop and weave together ideas discussed in her previous books. Enchantment is All About Us is the fifth book in the Living in a Magical World series. These books will challenge you to recognisethe traditional magic still alive in modern society, and empower you with a variety of skills and insights. Previous books by BeatriceWalditch from Heart of Albion You Don't Just Drink It! What you need to know – and do – before drinking mead Listening to the Stones (Volume One of the Living in a Magical World series) Knowing Your Guardians (Volume Two of the Living in a Magical World series) Learning From the Ancestors (Volume Three of the Living in a Magical World series) Everything is Change (Volume Four of the Living in a Magical World series) Living in a Magical World: Volume Five Enchantment is All About Us BeatriceWalditch Heart of Albion Enchantment is All About Us Beatrice Walditch ISBN978-1-905646-29-6 © Text copyright Beatrice Walditch2016 © illustrations copyright contributors 2016 minor revisions 2020 Front cover: Midwinter sunrise, Avebury, 2015. The moral rights of the author and illustrators have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior written permission from Heart of Albion, except for brief passages quoted in reviews. -

The Crucible and the Federal Rules of Evidence

Volume 115 Issue 2 Article 7 December 2012 Can Law and Literature Be Practical? The Crucible and the Federal Rules of Evidence Martin H. Pritikin Whittier Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Evidence Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Martin H. Pritikin, Can Law and Literature Be Practical? The Crucible and the Federal Rules of Evidence, 115 W. Va. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol115/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pritikin: Can Law and Literature Be Practical? The Crucible and the Federal CAN LAW AND LITERATURE BE PRACTICAL? THE CRUCIBLE AND THE FEDERAL RULES OF EVIDENCE Martin H. Pritikin* ABSTRACT Counter-intuitively, one of the best ways to learn the practice-oriented topic of evidence may be by studying a work of fiction-specifically, Arthur Miller's The Crucible, which dramatizes the seventeenth-century Salem witch trials. The play puts the reader in the position of legal advocate, and invites strategic analysis of evidentiary issues. A close analysis of the dialogue presents an opportunity to explore both the doctrinal nuances of and policy considerations underlying the most important topics covered by the Federal Rules of Evidence, including the mode and order of interrogation, relevance, character evidence and impeachment, opinion testimony, and hearsay. -

Protection Magick - Overview ©

Protection magick - overview © Questions? Feel free to raise any points at any time. You’ll find the notes of this session and detailed guidance on spells on our website = please take a card with you at the end. I’ve also put a file on the website on Blood Magick, which is yet another way of adding extra power to a spell. Like electricity or the wind, magick is a force of nature. We can’t see the wind or the lightning descending from the sky, but we can see the effects of these forces in the lightning ascending in a flash or the wind in the trees during a storm. Magick can be seen by its effects, but we can’t ladle out two spoonfuls of magick. Please, please try to remember that magick is a form of power – anyone can do magick, but it needs to be handled responsibly. OK then, let’s chat about WHY we need protection magick. Like any potentially dangerous force, one must take precautions when using magick. Take spiders as an example – my friend, Paul, keeps tropical spiders as pets. Some of them have urticarious fur (every hair follicle is tipped with poison to deter predators), which means that he must use thick gloves when handling a spider. So, when we talk protection magick, we’re actually talking about insurance, i.e. precautions to stop negative energy invading your space, upsetting your spells, affecting those you love and stopping any psychic attacks. It is a truism that some people will use magick for power, material gain, for revenge on someone or to bind another person, eg in a love spell. -

The Crucible

ROBERT WARD The Crucible (Libretto by Bernard Stambler, based on the play by Arthur Miller) PURCHASE OPERA PURCHASE SYMPHONY Jacque Trussel Hugh Murphy Artistic Director Conductor The Crucible Music......................................... Robert Ward PROGRAM NOTE.............John Ostendorf Libretto................................Bernard Stambler It is amusing to learn that playwright Arthur (based on the 1952 Arthur Miller play) Miller (1915-2005) first considered making The Conductor.................................Hugh Murphy Crucible an opera libretto, but was talked out Artistic Director..........................Jacque Trussel of it by composer-friend Mark Blitzstein. In- CAST: John Proctor...........................Bryan Murray stead, Miller created perhaps his most power- Elizabeth Proctor.................Rachel Weishoff ful stage play in 1953. It was inspired by the Abigail Williams....................Sylvia D’Eramo McCarthy witch-hunt of the 50s, during which Judge Danforth............... Joshua Benevento Miller himself was summoned in front of the Reverend Hale.....................Colin Whiteman House Un-American Activities Committee and Reverend Parris......................Ryan Capozzo cited for contempt of Congress when he re- Rebecca Nurse............................Iris Rogers fused to finger potential Communists in the Mary Warren ........................Soraya Karkari arts in this country. Tituba......................................Cara Collins Robert Ward (1917-2013), Cleveland born Giles Corey.............................John -

Collaborative Poppet Project (Effective Problem Solver) Ms

Collaborative Poppet Project (Effective Problem Solver) Ms. Santoro/Mrs. Watkins (Clothing-CBT)/Ms. Gambardella Due Date: _______________________ Period: _____ We are currently reading The Crucible. In Act II, Mary Warren gives Elizabeth a gift of a poppet, a type of doll. After the age of twelve poppets were no longer considered to be appropriate items for Puritan New England girls who began to assume greater everyday household duties. In some folktales, black magic and witchcraft can be found. A poppet is a doll made to represent a person. These dolls may be filled with natural materials that have been dried out to remove moisture, such as crushed sticks, leaves, dried lawn cuttings, grain, beans, crushed branches, or cloth stuffed with a bit of herbs. Some people believe herbs symbolize emotions, so one may choose to add a small amount of scent such as: cinnamon, cloves, sage, rosemary, or lavender. The use of sympathetic magic was not uncommon and poppets could be effigies. It was from these European dolls that the myth of Voodoo dolls arose. A poppet could potentially represent a person. In some cultures, the representation of a doll could be for good or evil. Therefore, although Elizabeth claimed she had none (poppet) since, “I were a girl” and she was long past the age of twelve, when the poppet was discovered in Goody Proctor’s home the circumstances aroused the suspicion of Reverend Hale. Denying ownership of a poppet, Elizabeth appeared to be lying and Mary Warren confirmed that she made the poppet and stuck the needle in it for safekeeping. -

Techniques of Modern Shamanism, Volume 3

TOUCHED BY FIRE TECHNIQUES OF MODERN SHAMANISM VOL.3 PHIL HINE Id like to acknowledge the following people, without whos ideas and inspiration this book would not have come about: Sheila Broun, Hannibal the Cannibal, Tracy Kennedy, Dave Lee, Colin Millard, Rodney Orpheus, Rich Westwood, and R.B.B. For Paul, with love & kisses Touched by Fire © Phil Hine 1989, Pagan News Publication.. This conversion to Acrobat PDF March 1998. Contact: Phil Hine BM COYOTE LONDON WC1N 3XX, UK Contents Introduction ......................................................... 5 Personal Reflections on Urban Shamanism ...... 7 Staking out the Territory.................................... 13 Social Wounds ................................................... 26 Magi-Prop ......................................................... 31 Looking to the Future?...................................... 36 Postscript ........................................................... 38 Appendices Activate The Bear: It’s A Teenage Rampage!... 40 TimeWind........................................................... 43 Also Published: Condensed Chaos, New Falcon Publications 1995 Prime Chaos, Chaos International 1993 The Pseudonomicon, Dagon Productions 1997 In Adobe Acrobat Format (Somewhere on the WWW): Oven-Ready Chaos PerMutations Running Magical Workshops: Notes for Facilitators Group Ego-Magick Exercises Awaiting Conversion: Walking Between The Worlds: Techniques of Modern Shamanism Vol.1 Two Worlds & Inbetween: The Worlds: Techniques of Modern Shamanism Vol.2 Chaos Servitors: A User -

Homemade Magic

HOMEMADE MAGIC: CONCEALED DEPOSITS IN ARCHITECTURAL CONTEXTS IN THE EASTERN UNITED STATES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY BY M. CHRIS MANNING DR. MARK GROOVER, ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2012 ABSTRACT THESIS: Homemade Magic: Concealed Deposits in Architectural Contexts in the Eastern United States STUDENT: M. Chris Manning DEGREE: Master of Arts in Anthropology COLLEGE: College of Sciences and Humanities DATE: December 2012 PAGES: 473 The tradition of placing objects and symbols within, under, on, and around buildings for supernatural protection and good luck, as an act of formal or informal consecration, or as an element of other magico-religious or mundane ritual, has been documented throughout the world. This thesis examines the material culture of magic and folk ritual in the eastern United States, focusing on objects deliberately concealed within and around standing structures. While a wide range of objects and symbols are considered, in-depth analysis focuses on three artifact types: witch bottles, concealed footwear, and concealed cats. This thesis examines the European origins of ritual concealments, their transmission to North America, and their continuation into the modern era. It also explores how culturally derived cognitive frameworks, including cosmology, religion, ideology, and worldview, as well as the concepts of family and household, may have influenced or encouraged the use of ritual concealments among certain groups. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis truly would not have been possible without the continuous love and encouragement of my family, especially my amazingly supportive parents, Michael and Mary Manning, and my sister, Becca, my rock, who’s always there when I need her, night or day. -

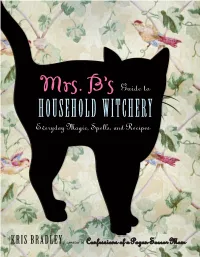

HOUSEHOLD WITCHERY Using Everyday Items and Ingredients, and Learn to Live Like a Domestic Witch! Everyday Magic, Spells, and Recipes

BRADLEY BE WITCHED, EVERY DAY IN EVERY WAY From anchovies to broccoli to wine and yeast, from sweeping the floor to blow-drying “Home is where the magic is! Kris Bradley your hair, you can change your life with Mrs. B’s a pinch of knowledge and a dash of magic. reminds us to make our home places sacred with her charming Let the domestic witch responsible for the ideas for ritualizing daily life. Confessions of a Pagan Soccer popular blog From kitchen to bedroom, here are Mom take you from room to room and ideas for every room, every day.” show you just how easy magic can be. —PATRICIA MONAGHAN, Guide to author of Magical Gardens: Mrs. B’s This book includes rituals, spells, simple Cultivating Soil and Spirit Sabbats for the busy witch and a complete Guide to materia magica of the kitchen pantry. Bring balance and enchantment back to your daily life HOUSEHOLD WITCHERY using everyday items and ingredients, and learn to live like a domestic witch! Everyday Magic, Spells, and Recipes HOUSEHOLD WITCHERY “Mrs. B “Mrs. B’s Guide to Household “Let Mrs. B show you how Witchery puts us in sync to protect your home from is undoubtedly with ourselves, family, home, negativity and harm, bless Paganism’s answer neighbors, and the world at and cleanse every room, and to Martha Stewart.” large. Mrs. B casts a good connect with traditional —EDAIN DUGUAY, spell, reversing dull housework household deities that can author of The Witchlets of drudgery into bright, guard over your home and Witches Brew series pleasurable, positive fulfillment.” aid you in your magic.” —GILLIAN KEMP, —CHRISTIAN DAY, author of The Good Spell Book author of The Witches Book and The Fortune-Telling Book of the Dead ISBN: 978-1-57863-515-3 U.S. -

Credits Special Thanks Contents

Credits Contents Writing & Game Design: Ross Leiser Additional Spells: Benjamin Huffman of Sterling Vermin Adventuring Shaman ................................................................................................... 1 Company Class Features ........................................................................................ 2 Editing: Eli Scovill Shaman Spell List ............................................................................. 4 Sensitivity Readers: Lynn Brown (Hoodoo and Voodoo), Jesse Spirit Guides ........................................................................................... 7 Craighead (Cherokee) Air Spirit .............................................................................................. 7 Ancestral Spirit .................................................................................. 7 Layout & Graphic Design: Taron Pounds Animal Spirit ...................................................................................... 8 Cover Artist: Isaac DeKing - Kraest Illustrations Benevolent Spirit ............................................................................... 8 Interior Artists: Daniel Comerci, Gary Dupuis, Forrest Imel, Vagelio Earth Spirit ......................................................................................... 9 Kaliva, Eric Lofgren, Joyce Maureira, Elizabeth Porter, Dean Fire Spirit ............................................................................................ 9 Spencer, Purple Duck Games, Emmanuel Bou Roldan, Ernanda Lost Spirit