Musical Dramaturgy in Craig Hella Johnson's Considerin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christa Anna Ockert L-Tage

Christa Anna Ockert L-Tage oder: "Hitler wird nicht bedient!" Verlag Autonomie und Chaos Leipzig – Berlin Christa Anna Ockert L-Tage Christa Anna Ockert (9. Dezember 1932 – 22. Oktober 2017) Herausgegeben von Petra Bern Diese Erinnerungen wurde von der Autorin Kapitel für Kapitel durchgesehen, korrigiert, ergänzt und autorisiert. Aufgrund chronischer Krankheit der Herausgeberin verzögerte sich die Fertigstellung der Arbeit. Herausgeberin und Verleger bedauern dies sehr! Liste der Episoden ab Seite 362 © 2020 Christa Anna Ockert (Erben) Originalausgabe im Verlag Autonomie und Chaos Leipzig – Berlin ISBN 978-3-945980-19-4 Diese online-Ausgabe kann für den Privatgebrauch kostenfrei heruntergeladen und ausgedruckt werden. Jede weitere Nutzung, insbesondere zu kommerziellen Zwecken, unterliegt der schriftlichen Genehmigung der RechteinhaberInnen. www.autonomie-und-chaos.berlin 2 Christa Anna Ockert L-Tage Was sagen Sie dazu? Ich hatte viele Namen. Fremde in meiner Kindheit konnten nur sehen, wie klein ich war, und sagten Mausi oder Mäuschen. (Großmutter, die mich kannte und nicht unterschätzte, nannte mich so vor dem Kindergarten.) Ich habe mich früh wie später nicht, wie anzunehmen wäre, in Mauselöcher verkrochen …! Die Pohlings riefen noch "de Kleene", als ich den Lehrlingsschuhen entwachsen war. Doch Mäusel mit sächsischem Zwielaut flüsterte und schmetterte mein geliebter zweiter Mann. Mutter machte keine Umstände und sagte – wie manche meiner Kolleginnen und Bekannten – Christa. Durch Giga, die Liebkosung meines Bruders Harald vor seiner Schulzeit, war ich hellhörig für das, was im Elternhaus fehlte… www.autonomie-und-chaos.berlin 3 Christa Anna Ockert L-Tage Ich hüpfte in den dreißiger Jahren an Vaters Hand durch Leipzig: Für Kurt Röller und andere seiner Freunde wurde ich Huppegra. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

2021 Contemporary Women Composers Music Catalog

Catalog of Recent Highlights of Works by Women Composers Spring 2021 Agócs, Kati, 1975- Debrecen Passion : For Twelve Female Voices and Chamber Orchestra (2015). ©2015,[2020] Spiral; Full Score; 43 cm.; 94 p. $59.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Immutable Dreams : For Pierrot Ensemble (2007). ©2007,[2020] Spiral; Score & 5 Parts; 33 $59.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Rogue Emoji : For Flute, Clarinet, Violin and Cello (2019). ©2019 Score & 4 Parts; 31 cm.; 42, $49.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Saint Elizabeth Bells : For Violoncello and Cimbalom (2012). ©2012,[2020] Score; 31 cm.; 8 p. $34.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Thirst and Quenching : For Solo Violin (2020). ©2020 Score; 31 cm.; 4 p. $12.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Albert, Adrienne, 1941- Serenade : For Solo Bassoon. ©2020 Score; 28 cm.; 4 p. $15.00 Los Angeles: Kenter Canyon Music Tango Alono : For Solo Oboe. ©2020 Score; 28 cm.; 4 p. $15.00 Los Angeles: Kenter Canyon Music Amelkina-Vera, Olga, 1976- Cloches (Polyphonic Etude) : For Solo Guitar. ©2020 Score; 30 cm.; 3 p. $5.00 Saint-Romuald: Productions D'oz DZ3480 9782897953973 Ensueño Y Danza : For Guitar. ©2020 Score; 30 cm.; 8 p. $8.00 Saint-Romuald: Productions D'oz DZ3588 9782897955052 Andrews, Stephanie K., 1968- On Compassion : For SATB Soli, SATB Chorus (Divisi) and Piano (2014) ©2017 Score - Download; 26 cm.; 12 $2.35 Boston: Galaxy Music 1.3417 Arismendi, Diana, 1962- Aguas Lustrales : For String Quartet (1992). ©2019 Score & 4 Parts; 31 cm.; 15, $40.00 Minot, Nd: Latin American Frontiers International Pub. -

Download Doppelte Singles

INTERPRET A - TITEL B - TITEL JAHR LAND FIRMA NUMMER 10 CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY NOTHING CAN 1978 D MERCURY 6008 035 10 CC GOOD MORNING JUDGE DON'T SQUEEZE 1977 D MERCURY 6008 025 10 CC I'M MANDY FLY ME HOW DARE YOU 1975 D MERCURY 6008 019 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE GOOD NEWS 1975 D MERCURY 6008 014 2 PLUS 1 EASY COME, EASY GO CALICO GIRL 1979 D PHONOGRAM 6198 277 3 BESOFFSKIS EIN SCHÖNER WEISSER ARSCH LACHEN IST 0D FLOWER BMB 2057 3 BESOFFSKIS HAST DU WEINBRAND IN DER BLUTBAHN EIN SCHEICH IM 0 D FLOWER 2131 3 BESOFFSKIS PUFF VON BARCELONA SYBILLE 0D FLOWER BMB 2070 3 COLONIAS DIE AUFE DAUER (DAT MALOCHELIED) UND GEH'N DIE 1985 D ODEON 20 0932 3 COLONIAS DIE BIER UND 'NEN APPELKORN WIR FAHREN NACH 0 D COLONGE 13 232 3 COLONIAS DIE ES WAR IN KÖNIGSWINTER IN D'R PHILHAR. 1988 D PAPAGAYO 1 59583 7 3 COLONIAS DIE IN AFRICA IST MUTTERTAG WIR MACHEN 1984 D ODEON 20 0400 3 COLONIAS DIE IN UNS'RER BADEWANN DO SCHWEMB HEY,ESMERALDA 1981 D METRONOME 30 401 3 MECKYS GEH' ALTE SCHAU ME NET SO HAGENBRUNNER 0 D ELITE SPEC F 4073 38 SPECIAL TEACHER TEACHER (FILMM.) TWENTIETH CENT. 1983 D CAPITOL 20 0375 7 49 ERS GIRL TO GIRL MEGAMIX 0 D BCM 7445 5000 VOLTS I'M ON FIRE BYE LOVE 1975 D EPIC EPC S 3359 5000 VOLTS I'M ON FIRE (AIRBUS) (A.H.) BYE LOVE 1975 D EPIC EPC S 3359 5000 VOLTS MOTION MAN LOOK OUT,I'M 1976 D EPIC EPC S 3926 5TH DIMENSION AQUARIUS DON'T CHA HEAR 1969 D LIBERTY 15 193 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS WISHING COMMITTED 1982 D JIVE 6 13 640 A LA CARTE DOCTOR,DOCTOR IT WAS A NIGHT 1979 D HANSA 101 080 A LA CARTE IN THE SUMMER SUN OF GREECE CUBATAO 1982 D COCONUT -

FLOWER INTO KINDNESS by Jake Runestad (Choral Score

JR0066-2 - RUNESTAD: FLOWER INTO KINDNESS Jake Runestad FLOWER INTO KINDNESS for chorus & string quartet Piano/Vocal Score Music jakerunestad.com TEXT FLOWER INTO KINDNESS The soul is made of love and must ever return to love. There is nothing so wise, nor so beautiful, nor so strong as love. (Mechthild von Magdeburg) Above all, love. I shed my words on the earth as the tree sheds its leaves. Let my thoughts unspoken f lower into kindness. (Rabindranath Tagore) PERFORMANCE TIME c. 5:30 ABOUT THE WORK This work is a movement from “Into the Light,” an extended work for chorus and orchestra, originally commissioned by Valparaiso University in commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. Christopher M. Cock, conductor, Valparaiso University Chorale, and director of the Bach Institute. Funded through the Hoermann-Koch Sacred Music Endowment at Valparaiso University. This new arrangement was created for Craig Hella Johnson and Conspirare, featured on their all-Runestad album “The Hope of Loving.” ABOUT THE COMPOSER Considered “one of the best of the younger American composers” (Chicago Tribune), award-winning composer and conductor Jake Runestad has received commissions and performances from leading ensembles such as VOCES8, the Philippine Madrigal Singers, Washington National Opera, the Netherlands Radio Choir, Seraphic Fire, the Swedish Radio Symphony, the Dallas Symphony Chorus, the Pacific Chorale, the Santa Fe Desert Chorale, and an all-Runestad album from Grammy-winning Craig Hella Johnson and Conspirare. Jake’s visceral music and charismatic personality have fostered a busy schedule of commissions, residencies, workshops, and conducting engagements, enabling him to share his passion for creativity, expressivity, and community with musicians around the world. -

Pike Kor Repertoire - 1996-97

AURORA - REPERTOIRE LIST - 1992-present Luther College, Decorah, Iowa Dr. Sandra Peter, conductor (updated August, 2010) Aurora is one of six auditioned choral ensembles at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa. Established in 1981, the group is comprised of 100 first-year women, selected each fall by audition. They perform on and off-campus for worship services, participate in the annual Christmas at Luther concert and Dorian Vocal Festival, and present a spring concert with the Norsemen, Luther‟s choral ensemble for first-year men. The choir has also participated in Luther performances of major choral/orchestral works, such as Beethoven‟s Mass in C major and Bach‟s The Passion according to St. John. Conducted by Dr. Sandra Peter since 1992, Aurora has performed at several regional conventions of the American Choral Directors Association. They released their first compact disc, Finding a voice, in 2006 and a second disc, Using our voice, in 2010. The word Aurora, Latin for dawn, represents the first light of day, or for these women, the beginning of their college experience and journey as independent scholars. Pike Kor was the name of this ensemble from the mid-1980s until the spring of 2008. AURORA – 2009-2010 In the time of Noah (from Three Alleluias) Amy Kucera Now I become myself Gwyneth Walker Steal away arr. James McKelvy O magnum mysterium Guy Forbes O come, o come, Emmanuel (premiere) arr. Sandra Peter Alleluia Paul Basler Kyrie Agneta Skøld Mir lächelt kein Frühling Johannes Brahms Friends Bob Chilcott The Gartan Mother‟s Lullaby (premiere) arr. Kathryn Lillich, S. -

The Role of Program Notes in Nonmusicians' Enjoyment of Choral

Texas Music Education Research 2016 The Role of Program Notes in Nonmusicians’ Enjoyment of Choral Music Samuel M. Parrott Texas State University Amy L. Simmons The University of Texas at Austin Background Performing musicians have a vested interest in understanding factors that can influence concertgoers’ enjoyment of live music, particularly when those in attendance have no extensive music training, no developed preference for the genre of music being performed, and are listening to music that is unfamiliar. The more information musicians have about factors that may increase listening enjoyment for nonmusicians, the better able they may be to deliberately enhance the concert experience. Psychologists and musicians have long studied variables that affect listeners’ responses to unfamiliar music and have described both musical and extra-musical factors that contribute to enjoyment. Regarding repertoire, we know that compositional elements of music typically affect listeners’ enjoyment (for a review, see Teo, 2003). Listeners tend to like melodies that follow scalar patterns, are predictable, and employ repetition that generates a measure of familiarity in the moment. Open and consonant harmonies (e.g., 4ths, 5ths, and octaves) are enjoyed more than dissonant ones (e.g., 2nds, 6ths, and 7ths), and listeners tend to like upbeat music that maintains tempo and incorporates steady rhythms. Taken together, Teo’s data suggest that listeners tend to like relatively simple music more than complex combinations of compositional elements. Teo’s review also states that the typical listener prefers instrumental over vocal music (with the exception of popular songs). Although this review did not address the influence of song lyrics or the text of classical choral pieces on listeners’ responses, the idea that lyrics and text may play a role in the enjoyment of these genres of music is worthy of investigation. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Summer Quarter 2019 (July - September) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

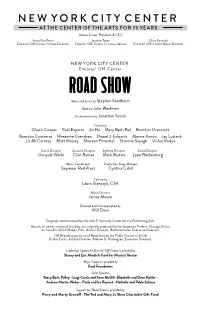

Read the Road Show Program

NEW YORK CITY CENTER AT THE CENTER OF THE ARTS FOR 75 YEARS Arlene Shuler, President & CEO Anne Kauffman Jeanine Tesori Chris Fenwick Encores! Off-Center Artistic Director Encores! Off-Center Creative Advisor Encores! Off-Center Music Director NEW YORK CITY CENTER Encores! Off-Center Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Featuring Chuck Cooper Raúl Esparza Jin Ha Mary Beth Peil Brandon Uranowitz Brandon Contreras Rheaume Crenshaw Daniel J. Edwards Marina Kondo Jay Lusteck Liz McCartney Matt Moisey Shereen Pimentel Sharone Sayegh Vishal Vaidya Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Donyale Werle Clint Ramos Mark Barton Leon Rothenberg Music Coordinator Production Stage Manager Seymour Red Press Cynthia Cahill Casting by Laura Stanczyk, CSA Music Director James Moore Directed and Choreographed by Will Davis Originally commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Bounce, an earlier version of this play, was originally produced by the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois on June 30, 2003 (Robert Falls, Artistic Director; Roche Schulfer, Executive Director). Off-Broadway premiere of Road Show by the Public Theater in 2008 (Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director; Andrew D. Hamingson, Executive Director). Leadership Support for Encores! Off-Center is provided by Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater Major Support is provided by Ford Foundation Series Sponsors Stacy Bash-Polley • Luigi Caiola and Sean McGill • Elizabeth and Dean Kehler • -

All-State Past Conductors

Minnesota Music Educators Association All-State Conductors Band Stephen Peterson, 2012 Tony Baker, 2004 Harold Bachmann, 1946 Captain Michelle Rakers, 2013 Juan Tony Guzman, 2005 Carleton Stewart, 1952 Craig Kirchhoff, 2014 James Carlson, 2006 Frank Piersol, 1956 Kevin Sedatole, 2015 Dean Sorenson, 2007 Lucien Cailliet, 1960 Jerry Luckhardt, 2016 Robert Washut, 2008 Frank Bencriscutto, 1962 Shanti Simon, 2017 Chris Vadala, 2009 Frank Bencriscutto, 1964 Betsy McCann, 2018 Trent Kynaston, 2010 Don McCatheran, 1965 Emily Threinen, 2019 Douglas Snapp, 2011 Miles Johnson, 1966 David Hagedorn, 2012 Karl Holvik, 1967 Symphonic Band Christopher Merz, 2013 Mayo Savold, 1968 Tom Swanson, 1999 Richard MacDonald, 2014 Frank Bencriscutto, 1969 Douglas Nimmo, 2000 Ellen Rowe, 2015 Charles Minelli, 1970 Matthew George, 2001 Miles Johnson, 1971 Tim Mahr, 2002 Jazz Band H. Robert Reynolds, 1972 Bruce Ammann, 2003 Ryan Frane, 2016 J. Robert Hanson, 1973 Richard Blatti, 2004 Matt Harris, 2017 John Paynter, 1974 Donald Schleicher, 2005 James (JC) Sanford, 2018 Frank Bencriscutto, 1975 Andrew Boysen, 2006 Patty Darling, 2019 Michael Polovitz, 1976 Russel Mikkelson, 2007 Frank Piersol, 1977 Gary Hill, 2008 Orchestra Frank Bencriscutto, 1978 Scott Weiss, 2009 Paul Oberg, 1944 J. Robert Hanson, 1979 Richard Heidel, 2010 Henry Sopkin, 1948 Miles Johnson, 1980 Frank Wickes, 2011 Gerald Samuel, 1954 George Regis, 1981 Takayoshi Suzuki, 2012 Antal Dorati, 1958 James Croft, 1982 James Spinazzola, 2013 Herman Hertz, 1962 Russell Pesola, 1983 Scott Hagen, 2014 Herman -

Wwciguide November 2019.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center This month, WTTW will bring you a film about the transformative power of 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 education. College Behind Bars follows twelve incarcerated men and women who hope to turn their lives around by earning a college degree, as we follow their Main Switchboard four-year journey through the famously rigorous Bard Prison Initiative. Join us (773) 583-5000 on two consecutive nights for a compelling documentary on America’s criminal Member and Viewer Services (773) 509-1111 x 6 justice system. Also on WTTW, The Chaperone reunites three talents from Downton Abbey – Websites actor Elizabeth McGovern, series creator Julian Fellowes, and director Michael wttw.com wfmt.com Engler – for this 1920s era story of a Kansas woman who accompanies an aspiring teen dancer on a tumultuous trip to New York City. A new series on WTTW Kids, Publisher Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum, introduces children aged 4-7 to historical Anne Gleason figures. On wttw.com, learn more about the small-town fraud that went on in Art Director Tom Peth Dixon, Illinois in our interview with the filmmaker of the documentary,All the WTTW Contributors Queen’s Horses. Julia Maish Lisa Tipton WFMT will present a live performance from New York’s Carnegie Hall by WFMT Contributors Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. And in observance of Andrea Lamoreaux Veterans Day, Chicago Tribune film critic Michael Phillips will present his sampling of music from war-themed movies old and new. -

Considering Matthew Shepard Composed & Conducted by CRAIG HELLA JOHNSON CONSPIRARE Craig Hella Johnson (B

Considering Matthew Shepard Composed & Conducted by CRAIG HELLA JOHNSON CONSPIRARE Craig Hella Johnson (b. 1962) Considering Matthew Shepard CONSPIRARE Commissioned by Fran and Larry Collmann and Conspirare CRAIG HELLA Johnson Dedicated to Philip Overbaugh PrologUE 1 (1 ) Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass MA 7’14 1 (18) Recitation VI KRh 0’22 2 (2) Ordinary Boy KRi, HK, MA, CH 6’56 2 (19) The Fence (one week later) MG 3’20 1 3 (3) We Tell Each Other Stories SM 4’06 3 (20) Recitation VII TS 0’28 2 56’22 4 (21 ) Stars JMi 3’17 49’04 Passion 5 (22) Recitation VIII MD 0’29 4 (4) Recitation I SB 0’36 6 (23) In Need of Breath DC 5’25 5 (5) The Fence (before) CB 2’33 7 (24) Gently Rest (Deer Lullaby) 4’22 6 (6) Recitation II DF 0’56 8 (25) Recitation IX JCC 0’43 7 (7) The Fence (that night) DB 5’52 9 (26) Deer Song SDT, EG, SM 4’12 8 (8) Recitation III MG 1’18 10 (27) Recitation X DB 0’33 9 (9) A Protestor 3’22 11 (28) The Fence (after) / The Wind 4’57 10 (10) Keep it Away From Me 12 (29) Pilgrimage SAW, CB, DF, RG, HK, JMi, KRi, SM, MG, SB, JCC, JMc 5’14 (The Wound of Love) LMW, Trio: SAW, SM, EG 3’51 11 (11 ) Recitation IV SAW 1’04 EpilogUE 12 (12) Fire of the Ancient Heart DB, CB 4’51 13 (30) Meet Me Here KRi, SAW 4’24 13 (13) Recitation V RG 0’39 14 (31 ) Thank You SM, DF 2’36 14 (14) Stray Birds 1’33 15 (32) All of Us SDT, MD, SM 6’06 15 (15) We Are All Sons (part 1) 0’40 16 (33) Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass (Reprise) MA 2’35 16 (16) I am Like You/We Are All Sons (part 2) Quartet: EG, KRi, CH, JP 7’35 17 (17) The Innocence MA 3’17 CONSPIRARE CRAIG HELLA Johnson Artistic Director and Conductor Soprano Alto Tenor Bass Instrumentalists Mela Dailey Sarah Brauer Matt Alber Cameron Beauchamp Vanguel Tangarov, clarinet Melissa Givens Janet Carlsen Campbell J.D.