Issue No. 455 April 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Opposition of a Leading Akhund to Shi'a and Sufi

The Opposition of a Leading Akhund to Shi’a and Sufi Shaykhs in Mid-Nineteenth- Century China Wang Jianping, Shanghai Normal University Abstract This article traces the activities of Ma Dexin, a preeminent Hui Muslim scholar and grand imam (akhund) who played a leading role in the Muslim uprising in Yunnan (1856–1873). Ma harshly criticized Shi’ism and its followers, the shaykhs, in the Sufi orders in China. The intolerance of orthodox Sunnis toward Shi’ism can be explained in part by the marginalization of Hui Muslims in China and their attempts to unite and defend themselves in a society dominated by Han Chinese. An analysis of the Sunni opposition to Shi’ism that was led by Akhund Ma Dexin and the Shi’a sect’s influence among the Sufis in China help us understand the ways in which global debates in Islam were articulated on Chinese soil. Keywords: Ma Dexin, Shi’a, shaykh, Chinese Islam, Hui Muslims Most of the more than twenty-three million Muslims in China are Sunnis who follow Hanafi jurisprudence when applying Islamic law (shariʿa). Presently, only a very small percentage (less than 1 percent) of Chinese Muslims are Shi’a.1 The historian Raphael Israeli explicitly analyzes the profound impact of Persian Shi’ism on the Sufi orders in China based on the historical development and doctrinal teachings of Chinese Muslims (2002, 147–167). The question of Shi’a influence explored in this article concerns why Ma Dexin, a preeminent Chinese Muslim scholar, a great imam, and one of the key leaders of the Muslim uprising in the nineteenth century, so harshly criticized Shi’ism and its accomplices, the shaykhs, in certain Sufi orders in China, even though Shi’a Islam was nearly invisible at that time. -

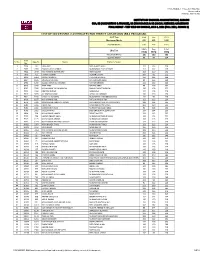

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:01/02/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: ABBASIN 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1969. POB: Sheykhan village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan a.k.a: MAHSUD, Abdul Aziz Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0121 (UN Ref): TAi.155 (Further Identifiying Information):Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we- work/Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 21/10/2011 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 12156. 2. Name 6: ABDUL AHAD 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Mr DOB: --/--/1972. POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Nationality: Afghan National Identification no: 44323 (Afghan) (tazkira) Position: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0094 (UN Ref): TAi.121 (Further Identifiying Information): Belongs to Hotak tribe. Review pursuant to Security Council resolution 1822 (2008) was concluded on 29 Jul. 2010. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/ Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 23/02/2001 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 7055. -

Afghan National Arrested for 2008 Abduction of American Journalist

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------- X UNITED STATES OF AMERICA -v. - SEALED INDICTMENT HAJI NAJIBULLAH, 14 Cr. a/k/a "Najibullah Nairn," a/k/a "Abu Tayeb," a/k/a "Atiqullah," AKHUND ZADA, a/k/a "Amir Ashraf," and .J TIMOR SHAH, Defendants. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X COUNT ONE The Grand Jury charges: 1. From on or about November 10, 2008, up to and including in or about July 2009, in an offense occurring in and affecting interstate and foreign commerce, HAJI NAJIBULLAH, a/k/a "Najibullah Nairn," a/k/a "Abu Tayeb," a/k/a "Atiqullah," AKHUND ZADA, a/k/a "Amir Ashraf," and TIMOR SHAH, the defendants, at least one of whom will be first brought to and arrested in the Southern District of New York, and others known and unknown, willfully and knowingly seized and detained and threatened to kill, injure, and continue to detain other persons, namely, a national of the United States and two nationals of Afghanistan, and aided and abetted the same, in order to compel a third person, a governmental organization, and the United States Government to do and abstain from doing an act as an explicit and implicit condition for the release of the persons detained, to wit, the defendants, and others known and unknown, detained and threatened to kill an American journalist and two Afghan citizens in Afghanistan, and, in exchange for the release of the three hostages, demanded money from the American journalist's family and the release of Taliban prisoners by the United States Government. (Title 18, United States Code, Sections 1203(a), 3238 and 2.) COUNT TWO The Grand Jury further charges: 2. -

Ethnohistory of the Qizilbash in Kabul: Migration, State, and a Shi'a Minority

ETHNOHISTORY OF THE QIZILBASH IN KABUL: MIGRATION, STATE, AND A SHI’A MINORITY Solaiman M. Fazel Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology Indiana University May 2017 i Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Raymond J. DeMallie, PhD __________________________________________ Anya Peterson Royce, PhD __________________________________________ Daniel Suslak, PhD __________________________________________ Devin DeWeese, PhD __________________________________________ Ron Sela, PhD Date of Defense ii For my love Megan for the light of my eyes Tamanah and Sohrab and for my esteemed professors who inspired me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This historical ethnography of Qizilbash communities in Kabul is the result of a painstaking process of multi-sited archival research, in-person interviews, and collection of empirical data from archival sources, memoirs, and memories of the people who once live/lived and experienced the affects of state-formation in Afghanistan. The origin of my study extends beyond the moment I had to pick a research topic for completion of my doctoral dissertation in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University. This study grapples with some questions that have occupied my mind since a young age when my parents decided to migrate from Kabul to Los Angeles because of the Soviet-Afghan War of 1980s. I undertook sections of this topic while finishing my Senior Project at UC Santa Barbara and my Master’s thesis at California State University, Fullerton. I can only hope that the questions and analysis offered here reflects my intellectual progress. -

Proquest Dissertations

Imam Kashif al-Ghita, the reformist marji' in the Shi'ah school of Najaf Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Abbas, Hasan Ali Turki, 1949- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 13:00:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282292 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from aity type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

BB0AH >5 C4A<B

6;>BB0AH>5C4A<B A4;0C43C>8B;0<0=3<DB;8<2><<D=8C84B 8=8=C4AA468>=0;B4CC8=6B A product of the “Presenting Islam and Muslim Communities in Context” Workshop Funded by a grant from the Social Sciences Research Council (SSRC) 24=C4A5>A<833;440BC4A=BCD384B70AE0A3D=8E4AB8CH "':8A:;0=3BCA44C20<1A8364<0! "'DB0 C4;)% &#($#$$50G)% &#(%'$'#2<4B/50B70AE0A343D Where this list of terms comes from: This set of definitions is an attempt to create a contextualized list of important terms relating to Muslims and Islamic societies. It has been put together by people associated with the Presenting Islam and Muslim Communities in Context workshop, which was held at Harvard University on 14 and 15 November 2008. The authors recognize that on every issue involving religious questions a wide variety of opinions, translations and understandings of selected topics may be found. They have tried to acknowledge a variety of understandings in these definitions, however, any attempt to define is by its nature selective. The authors welcome suggestions from readers on any and all of these definitions. Please note that the definitions have not been peer reviewed but have been written in consideration of serving a diverse audience of media practitioners and have been contextualized as much as possible. The Associated Press Style Guide has been consulted for grammar and spelling. Authorship is noted to be people associated with the Presenting Islam and Muslim Communities in Context workshop. 6;>BB0AH>5C4A<BA4;0C43C>8B;0<0=3<DB;8< 2><<D=8C84B8=8=C4AA468>=0;B4CC8=6B 2>=C4=CB # Ahl al-Kitab $ Ayatollah % Caliph/Caliphate & Hadith ' Hajj ( Hijab Imam Ismaili ! Ithna Ashari (Twelver) Shia " Jihad # Kafir/Takfir $ Pillars of Islam % Qur’an & Ramadan ' Salat ( Sawm ! Shahadah ! Shariah !! Shia !" Sufi/Sufi Order !# Sunni !$ Ulama !% Ummah !& Wahhabi !' Zakat *Note: Arabic terms considered loanwords in English are shown in plain text. -

The Struggle of the Shi'is in Indonesia

The Struggle of the Shi‘is in Indonesia The Struggle of the Shi‘is in Indonesia by Zulkifli Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zulkifli. Title: The struggle of the Shi’is in Indonesia / Zulkifli. ISBN: 9781925021295 (paperback) 9781925021301 (ebook) Subjects: Shiites--Indonesia. Shīʻah--Relations--Sunnites. Sunnites--Relations--Shīʻah. Shīʻah--Indonesia--History. Minorities--Indonesia--History. Dewey Number: 297.8042 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. For many of the authors in this series, English is a second language and their texts reflect an appropriate fluency. -

Domestic Barriers to Dismantling the Militant Infrastructure in Pakistan

[PEACEW RKS [ DOMESTIC BARRIERS TO DISMANTLING THE MILITANT INFRASTRUCTURE IN PAKISTAN Stephen Tankel ABOUT THE REPORT This report, sponsored by the U.S. Institute of Peace, examines several underexplored barriers to dismantling Pakistan’s militant infrastructure as a way to inform the understandable, but thus far ineffectual, calls for the coun- try to do more against militancy. It is based on interviews conducted in Pakistan and Washington, DC, as well as on primary and secondary source material collected via field and desk-based research. AUTHOR’S NOTE:This report was drafted before the May 2013 elections and updated soon after. There have been important developments since then, including actions Islamabad and Washington have taken that this report recommends. Specifically, the U.S. announced plans for a resumption of the Strategic Dialogue and the Pakistani government reportedly developed a new counterterrorism strategy. Meanwhile, the situation on the ground in Pakistan continues to evolve. It is almost inevitable that discrete ele- ments of this report of will be overtaken by events. Yet the broader trends and the significant, endogenous obstacles to countering militancy and dismantling the militant infrastruc- ture in Pakistan unfortunately are likely to remain in place for some time. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Stephen Tankel is an assistant professor at American University, nonresident scholar in the South Asia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and author of Storming the World Stage: The Story of Lashkar- e-Taiba. He has conducted field research on conflicts and militancy in Algeria, Bangladesh, India, Lebanon, Pakistan, and the Balkans. Professor Tankel is a frequent media commentator and adviser to U.S. -

Blood-Stained Hands Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan’S Legacy of Impunity

Blood-Stained Hands Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan’s Legacy of Impunity Human Rights Watch Copyright © 2005 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-334-X Cover photos: A mujahedin fighter in Kabul, June 1992. © 1992 Ed Grazda Civilians fleeing a street battle in west Kabul, March 5, 1993. © 1993 Robert Nickelsberg Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: 1-(212) 290-4700, Fax: 1-(212) 736-1300 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel:1-(202) 612-4321, Fax:1-(202) 612-4333 [email protected] 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road London N1 9HF, UK Tel: 44 20 7713 1995, Fax: 44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] Rue Van Campenhout 15, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: 32 (2) 732-2009, Fax: 32 (2) 732-0471 [email protected] 9 rue Cornavin 1201 Geneva Tel: + 41 22 738 04 81, Fax: + 41 22 738 17 91 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To receive Human Rights Watch news releases by email, subscribe to the HRW news listserv of your choice by visiting http://hrw.org/act/subscribe- mlists/subscribe.htm Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. -

Taliban Views on a Future State

TALIBAN VIEWS ON A FUTURE STATE BORHAN OSMAN AND ANAND GOPAL Introduction by Barnett Rubin N Y U CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL C I C COOPERATION July 2016 CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION The world faces old and new security challenges that are more complex than our multilateral and national institutions are currently capable of managing. International cooperation is ever more necessary in meeting these challenges. The NYU Center on International Cooperation (CIC) works to enhance international responses to conflict and insecurity through applied research and direct engagement with multilateral institutions and the wider policy community. CIC’s programs and research activities span the spectrum of conflict insecurity issues. This allows us to see critical inter-connections between politics, security, development and human rights and highlight the coherence often necessary for effective response. We have a particular concentration on the UN and multilateral responses to conflict. TABLE OF CONTENTS TALIBAN VIEWS ON A FUTURE STATE By Borhan Osman and Anand Gopal ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 ABOUT THE AUTHORS 5 INTRODUCTION 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 KEY FINDINGS 6 INTRODUCTION 8 POWER SHARING: WHO BELONGS IN THE NEW ORDER? 10 Power Sharing Today 12 ISLAM AND THE FUTURE STATE 16 Political Representation 19 WHOSE ISLAM? 22 Evolution 25 CONCLUSION 30 ENDNOTES 33 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank Edmund Haley for helping conceive of this project and the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (UK) for its support. The Afghanistan-Pakistan Regional Program of the Center on International Cooperation would like to thank the government of Norway for its support, without which it would not have been able to publish this report. -

Perspectives on Terrorism, Volume 8, Issue 1

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 8, Issue 1 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editors 1 I. Articles Perspectives on Counterterrorism: From Stovepipes to a Comprehensive Approach 2 by Ronald Crelinsten Analysing Terrorism from a Systems Tinking Perspective 16 by Lukas Schoenenberger, Andrea Schenker-Wicki and Mathias Beck Evidence-Based Counterterrorism or Flying Blind? How to Understand and Achieve What Works 37 by Rebecca Freese Discovering bin-Laden’s Replacement in al-Qaeda, using Social Network Analysis: A Methodological Investigation 57 by Edith Wu, Rebecca Carleton, and Garth Davies II. Research Notes Boko Haram’s International Reach 74 by Ely Karmon III. Resources Bibliography: Non-English Academic Dissertations on Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism 84 by Eric Price Bibliography: Terrorism Research Literature (Part 1) 99 by Judith Tinnes IV. Book Reviews “Counterterrorism Bookshelf” – 23 Books on Terrorism & Counter-terrorism Related Subjects 133 by Joshua Sinai V. Op-Ed A Primer to the Sunni-Shia Confict 142 by Philipp Holtmann VI. News from TRI’s Country Networks of PhD Tesis Writers i February 2014 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 8, Issue 1 Spain and Brazil 146 VII. Notes from the Editors About Perspectives on Terrorism 149 ii February 2014 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 8, Issue 1 Welcome from the Editors Dear Reader, We are pleased to announce the release of Volume VIII, Issue 1 (February 2014) of Perspectives on Terrorism at www.terrorismanalysts.com. Our free online journal is a joint publication of theTerrorism Research Initiative (TRI), headquartered in Vienna, and the Center for Terrorism and Security Studies (CTSS), headquartered at the University of Massachusetts’ Lowell campus.