Country of Origin Information Report Nigeria (March 2021)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Philanthropy Forum Conference April 18–20 · Washington, Dc

GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 18–20 · WASHINGTON, DC 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Prior to publication, the authors were given the opportunity to review their remarks. Some have made minor adjustments. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team—Suzy Antounian, Bayanne Alrawi, Laura Beatty, Noelle Germone, Deidre Graham, Elizabeth Haffa, Mary Hanley, Olivia Heffernan, Tori Hirsch, Meghan Kennedy, DJ Latham, Jarrod Sport, Geena St. Andrew, Marla Stein, Carla Thorson and Anna Wirth—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Newman’s Own Foundation USAID The David & Lucile Packard The MasterCard Foundation Foundation Anonymous Skoll Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation Skoll Global Threats Fund Margaret A. Cargill Foundation The Walton Family Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation The World Bank IFC (International Finance SUPPORTING MEMBERS Corporation) The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust MEMBERS Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Anonymous Humanity United Felipe Medina IDB Omidyar Network Maja Kristin Sall Family Foundation MacArthur Foundation Qatar Foundation International Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

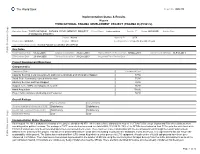

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Nigeria: Marriage Certificates, Including Their Appearance And

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?... Nigeria: Marriage certificates, including their appearance and security features; requirements and procedure to obtain them from within the country or from abroad; prevalence of fraudulent documents (2018–October 2020) 1. Marriage Registration According to sources, Nigerian laws recognize Islamic, customary and statutory [registry (US n.d.)] marriages (Nigeria n.d.a; Doma-Kutigi, 2019, 25). A journal article on certifying Islamic marriages in Nigeria by Halima Doma-Kutigi, who teaches law at Nasarawa State University and Baze University in Nigeria, indicates that each marriage type is "distinct and separate" from the others (Doma-Kutigi 2019, 22, 23), while the US reciprocity schedule explains that specific requirements apply to each one (US n.d.). Sources report that customary and Islamic marriages are not required to be registered (US n.d.; Doma-Kutigi 2019, 22) or have no government record (Nigeria n.d.a). The US Department of State's reciprocity schedule states that [i]ndividuals will sometimes, when necessary, swear an affidavit in a court that they are married in order to provide written proof of such a marriage. Some Local Governments will issue a certificate based on that affidavit by virtue of the Registration of Customary Marriage [by-l]aws. Absence of an affidavit or certificate of this kind cannot be taken as lack of marital status. (US n.d.) Doma-Kutigi indicates that by-laws allowing local authorities to register customary marriage exist in "most" states (Doma-Kutigi 2019, 29). -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

Gay Rights Policy and the United States-Nigeria Diplomatic Relations

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume V, Issue VII, July 2021|ISSN 2454-6186 Gay Rights Policy and the United States-Nigeria Diplomatic Relations Akuche, Andre Ben-Moses Assistant Lecturer, Department of International Relations, Madonna University, Nigeria Abstract: The study assessed the nexus between gay rights policy the rights of gays and lesbians everywhere (Barack and the United States-Nigeria diplomatic relations, 2006-2015. Obama, UNGA, September 2011). Relations between both countries have been cordial except during military rule in Nigeria. The low moments of their As a corroborative evidence to the U.S. foreign policy on gay diplomatic relations since democratic rule in 1999 was evident rights under the President Obama‟s leadership, the United during 2013-2015 and it was centered on the controversy generated especially, by the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) States is a liberal democracy whose constitution underpins Act, 2013 and failed leadership. Hence, the study specifically, is liberty, justice, and equality and as a result, the country holds to (i) ascertain whether the criminalisation of gay rights in the belief that, every human being anywhere is born free and Nigeria undermined the existing diplomatic relations between the should be accorded liberty of free will to live under state United States and Nigeria, and, to (ii) determine whether protection. It is also the duty of government to dispense leadership role in Nigeria accounted for the pressure by the justice without fear or favour of anyone, and all individuals United States for the decriminalisation of gay rights in Nigeria. should enjoy equal rights as members of a political The theoretical perspective of this study is rooted in the ‘centre- community. -

Algemeen Ambtsbericht Nigeria Juni 2018

Algemeen ambtsbericht Nigeria Datum 27 juni 2018 Pagina 1 van 77 Algemeen ambtsbericht Nigeria | juni 2018 Colofon Plaats Den Haag Opgesteld door Directie Sub-Sahara Afrika Cluster Ambtsberichten (DAF/CAB) Pagina 2 van 77 Algemeen ambtsbericht Nigeria | juni 2018 Inhoudsopgave Colofon ..........................................................................................................2 Inhoudsopgave ...............................................................................................3 Inleiding .........................................................................................................5 1 Landeninformatie ........................................................................................ 7 1.1 Politieke ontwikkelingen ...................................................................................7 1.2 Veiligheidssituatie .......................................................................................... 13 1.2.1 Noord-Centraal zone (Niger, Kogi, Benue, Plateau, Nasarawa, Kwara en FCT) ....... 14 1.2.2 Noordoost zone (Bauchi, Borno, Taraba, Adamawa, Gombe en Yobe) ................... 16 1.2.3 Noordwest zone (Zamfara, Sokoto, Kaduna, Kebbi, Katsina, Kano en Jigawa) ....... 19 1.2.4 Zuidwest zone (Oyo, Ekiti, Osun, Ondo, Lagos en Ogun) .................................... 20 1.2.5 Zuid-Zuid zone (Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Edo, Rivers) ................. 21 1.2.6 Zuidoost zone (Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu en Imo) ...................................... 23 1.3 Documenten ................................................................................................ -

011 Corruption Reporting in the Media in the 2015 Nigerian Elections

Working Paper 011 Corruption Reporting in the Media in the 2015 Nigerian Elections: Setting the Agenda or Toeing the Line? Adeshola Komolafe1, Elor Nkereuwem2, Oliver Kalu-Amah3 July 2019 1,2,3 OAK Center for Journalism Development (OCJD) Correspondence to: Adeshola Komolafe ([email protected]) Corruption Reporting in the Media in the 2015 Nigerian Elections: Setting the Agenda or Toeing the Line? Contents Executive summary 3 1. Corruption, elections and the media 4 2. Corruption reportage and Nigeria’s 2015 elections 9 3. Consequence mapping 25 4. Conclusion 30 References 31 Figures Figure 1: Corruption coverage in 2014 11 Figure 2: Corruption coverage in 2015 11 Figure 3: Nigeria’s 2015 election cycle 12 Figure 4: 2014 media coverage of the Dasuki scandal 13 Figure 5: 2015 media coverage of the Dasuki scandal 14 Figure 6: Cross-section of newspaper coverage of the Diezani scandal 15 Figure 7: 2014 and 2015 coverage of the Malabu scandal 16 Figure 8: 2014 and 2015 coverage of corruption stories involving prominent politicians 17 Figure 9: 2014 corruption coverage by newspaper 20 Figure 10: 2014 corruption coverage by newspaper 20 Figure 11: 2014 coverage by corruption category 21 Figure 12: 2015 coverage by corruption category 21 Figure 13: Fraud coverage in 2014 and 2015 22 Figure 14: Theft coverage in 2014 and 2015 22 Figure 15: Diversion of funds coverage in 2014 and 2015 22 Figure 16: Bribery coverage in 2014 and 2015 22 Figure 17: Monthly trends in corruption and anti-corruption reporting 23 Figure 18: Policy outcomes from media -

Living Through Nigeria's Six-Year

“When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency About the Report This report explores the experiences of civilians and armed actors living through the conflict in northeastern Nigeria. The ultimate goal is to better understand the gaps in protection from all sides, how civilians perceive security actors, and what communities expect from those who are supposed to protect them from harm. With this understanding, we analyze the structural impediments to protecting civilians, and propose practical—and locally informed—solutions to improve civilian protection and response to the harm caused by all armed actors in this conflict. About Center for Civilians in Conflict Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) works to improve protection for civil- ians caught in conflicts around the world. We call on and advise international organizations, governments, militaries, and armed non-state actors to adopt and implement policies to prevent civilian harm. When civilians are harmed we advocate the provision of amends and post-harm assistance. We bring the voices of civilians themselves to those making decisions affecting their lives. The organization was founded as Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a courageous humanitarian killed by a suicide bomber in 2005 while advocating for Iraqi families. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] www.civiliansinconflict.org © 2015 Center for Civilians in Conflict “When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency This report was authored by Kyle Dietrich, Senior Program Manager for Africa and Peacekeeping at CIVIC. -

Tracking Displacement in the Lake Chad Basin

WITHIN AND BEYOND BORDERS: TRACKING DISPLACEMENT IN THE LAKE CHAD BASIN Regional Displacement and Human Mobility Analysis Displacement Tracking Matrix December 2016 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION (IOM) DTM activities are supported by: Chad │Cameroon│Nigeria 1 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community: to assist in meeting the growing operational challenges of migration management; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. PUBLISHER International Organization for Migration, Regional Office for West and Central Africa, Dakar, Senegal © 2016 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 2 IOM Regional Displacement Tracking Matrix INTRODUCTION Understanding and analysis of data, trends and patterns of human mobility is key to the provision of relevant and targeted humanitarian assistance. Humanitarian actors require information on the location and composition of the affected population in order to deliver services and respond to needs in a timely manner. -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

Nigeria AFP PROJECT

AFP Partners Mee6ng, Bal6more, MD Nigeria AFP PROJECT - Progress Update Pathfinder Internaonal Nigeria/ Planned Parenthood Federa,on of Nigeria (PPFN) Tuesday, March 17, 2015 ADVANCE FAMILY PLANNING (AFP) PROJECT v AFP in Lagos State v 3rd Nigeria FP Conference, Abuja v Accelerang Contracep6ve Choice (ACC) in Nigeria o Planning Mee6ng o ACC Convening § FP Advocates/SMOH FP managers from Gombe, Kaduna, Kebbi, Lagos, Kwara, Oyo and the FCT par6cipated § States iden6fied FP priori6es and developed advocacy objec6ves for such v Lagos AFP SMART®/ImpactNow® Training v NACC Follow up in Kwara, Kebbi, and Kaduna States § Follow up outstanding for Gombe state v FH+ Advocacy Working Group Training § Follow up for Oyo state STATE PRIORITIES/OBJECTIVES STATE OBJECTIVES OUTCOMES Gombe 1. To secure funding to “step down” trainings on injectables and LARCs for 250 Post NACC CHEWS and 50 midwives respecvely in Gombe State by Dec follow up 2015.OperaHonalizing task-shiQing policy in Gombe State outstanding Kebbi 1. Quick release of budgeted funds by Q1 of 2015 in Kebbi State. Advocacy workplan 2. Public awareness/educaon through state-owned media star6ng from June developed and budgeted 2015. 3. Local government to allocate money for FP/RH star6ng from June 2015. Kwara 1. Prompt release of approved funds for FP in Kwara State by end of Q3 2015. Advocacy workplan 2. Develop a costed implementaon plan (CIP) for FP in Kwara State based on developed and budgeted the Naonal FP Blueprint by end of Oct 2015. Lagos 1. In public health centers (PHCs), 30% LGAs/LCDAs to allocate funding for Advocacy workplan family planning consumables. -

Poverty in the North-Western Part of Nigeria 1976-2010 Myth Or Reality ©2019 Kware 385

Sociology International Journal Review Article Open Access Poverty in the north-western part of Nigeria 1976- 2010 myth or reality Abstract Volume 3 Issue 5 - 2019 Every society was and is still affected by the phenomenon of poverty depending on the Aliyu A Kware nature and magnitude of the scourge. Poverty was there during the time of Jesus Christ. Department of History, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Nigeria Indeed poverty has been an issue since time immemorial, but it has become unbearable in recent decades particularly in Nigeria. It has caused a number of misfortunes in the country Correspondence: Aliyu A Kware, Department of History, including corruption, insecurity and general underdevelopment. Poverty has always been Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria, Tel 0803 636 seen as negative, retrogressive, natural, artificial, man-made, self-imposed, etc. It is just 8434, Email some years back that the Federal Office of Statistics (FOS, NBS) has reported that Sokoto State was the poorest State in Nigeria, a statement that attracted serious heat back from Received: August 14, 2019 | Published: October 15, 2019 the Government of the State. The Government debunked the claim, saying that the report lacked merit and that it was politically motivated. In this paper, the author has used his own research materials to show the causes of poverty in the States of the North-western part of Nigeria during the period 1976 to 2010, and as well highlight the areas in the States, which have high incidences of poverty and those with low cases, and why in each case. Introduction However, a common feature of the concepts that relate to poverty is income, but that, the current development efforts at poverty North-western part of Nigeria, in this paper, refers to a balkanized reduction emphasize the need to identify the basic necessities of life part of the defunct Sokoto Caliphate.