Interviewers on the Art and Craft of Interviewing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Address at Asia Society and Asialink at the University of Melbourne, by Hillary Rodham Clinton

Address at Asia Society and Asialink at the University of Melbourne, by Hillary Rodham Clinton Hillary Rodham Clinton: An Australian Conversation Sunday, November 7, 2010 TRANSCRIPT LEIGH SALES: Hello I'm Leigh Sales. Welcome to this ABC News special; Hillary Rodham Clinton, an Australian conversation. Let me explain today's format. The Secretary of State will address our audience here in Melbourne for about 10 minutes or so and I'll briefly interview her afterwards. I'll then open the floor to questions from our audience, which will go for about three quarters of an hour. In our discussion we'll also include a handful of the hundreds of questions we received from all around the country via Twitter and Facebook and also on video. To introduce the Secretary of State here's the University of Melbourne's Vice Chancellor, Professor Glyn Davis. (applause) GLYN DAVIS: Leigh thank you. Foreign Minister; Ambassador; Chancellor; colleagues, friends. Good morning and welcome to the University of Melbourne. It's an enormous pleasure to welcome you on what's going to be a very special event. It's a special honour to welcome an outstanding global policy maker and leader the United States Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton to our campus this morning. This is an extraordinary opportunity to hear from and to engage with Secretary Clinton, who is in Australia for the regular military, political and security talks between the governments of Australia and the United States starting tomorrow. Today's direct engagement with the Secretary suggests a welcome openness to dialogue and discussion. -

2018 SWF Live and Local Speakers April 18, 2018

2018 SWF Live and Local Speakers April 18, 2018 Name Bio Recent works Alec Luhn is the Russia correspondent for The Daily Telegraph and has previously written for Time, Politico, The New York Times and The Guardian , among others. He covered the Russian protest Alec Luhn movement, the Sochi Olympics, the annexation of Crimea and the revolution and war in Ukraine. He is working on a book related to the Russian interference in the 2016 US election. Alexis Okeowo is a magazine writer and screenwriter, and a former fellow at New America. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine , the Financial Times , The Best American Travel Writing , and The Best American Sports Writing . The daughter of immigrant parents, Okeowo grew Alexis A Moonless, Starless Sky: Ordinary Women up in Alabama and attended Princeton University. She was based in Lagos, Nigeria, from 2012 to 2015, Okeowo and Men Fighting Extremism in Africa and now lives in Brooklyn. Her first book, A Moonless, Starless Sky: Ordinary Women and Men Fighting Extremism In Africa , is a vivid narrative of Africans who are courageously resisting their continent’s wave of fundamentalism. Aminatou Sow is founder of Tech LadyMafia, a group that increases opportunities for women in Tech and the co-host of Call Your Girlfriend , a podcast that tackles the intricacies of pop culture and the latest in Aminatou politics every single week. A digital strategist and writer, she was named one of Forbes 30 Under 30 in Sow Tech. She is also a member of the Sundance Institute Director's Advisory Group and previously led Social Impact Marketing at Google. -

Justin Stevens Announced As New Executive Producer of 7.30

RELEASED: Monday 4th December Justin Stevens announced as new Executive Producer of 7.30 Justin Stevens has been announced as the new Executive Producer of ABC nightly current affairs flagship 7.30. Currently a producer on Four Corners, Stevens started his career at the Nine Network before moving to the ABC in 2006, working as producer for first Kerry O’Brien and then Leigh Sales on 7.30. His other roles have included being Producer on the acclaimed series Keating: The Interviews with Kerry O’Brien, Supervising Producer on 7.30 and Producer on the AACTA and Logie Award-winning documentary The Killing Season. His work on Four Corners has included producing the Walkley-nominated two-part special on the Lindt Café Siege, Hillary Clinton: The Interview, a profile on Clive Palmer, an investigation into match-fixing in tennis and the 2016 election special. Stevens takes over from Sharon O’Neill, who has been Acting EP since Jo Puccini vacated the role to lead ABC Investigations. O'Neill has been appointed Supervising Producer of Stan Grant’s new nightly show on the ABC NEWS television channel. ABC Director, News Gaven Morris said: "Leading 7.30 is one of the most challenging and best jobs in Australian journalism and Justin is a terrific appointment to this role. "With the recent announcement of Sam Clark’s appointment as EP of Insiders, I’m proud and excited that outstanding younger leaders are stepping forward from within ABC NEWS ranks.” ABC NEWS Head of Investigative and In-depth Journalism John Lyons said: "Under Jo Puccini and Sharon O’Neill, 7.30 has been a powerhouse of investigative journalism, regularly producing important, high-impact public interest journalism. -

Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, Iview, Radio and Online

Media Release: 05.05.17 Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, iview, radio and online abc.net.au/news The 2017 Federal Budget will be handed down on Tuesday May 9 and the ABC has the best independent coverage on all platforms. We’ll have the first interview with Treasurer Scott Morrison, as well as in-depth analysis and expert commentary from the ABC’s leading political and business teams. What does Budget 2017 mean for you? Know the numbers, the politics, and the impact with ABC NEWS. Tuesday, 9 May – BUDGET DAY TELEVISION – ABC, the ABC NEWS channel & iview The Drum - 5.30pm on ABC & iview / 6.30pm AEST on the ABC NEWS channel As the press gallery bunkers down in the budget media lock-up, host John Barron and a panel of experts will count down to Budget 2017 and preview what to expect. ABC NEWS - 7pm on ABC & iview The news of the day and the lead up to the Federal Treasurer’s Budget speech. ABC NEWS BUDGET 2017 SPECIAL - on ABC, the ABC NEWS channel, iview, ABC NEWS online and simulcast live on the ABC News Facebook page. Leigh Sales hosts the ABC NEWS Budget 2017 special with Political Editor Chris Uhlmann live from Parliament House in Canberra. At 7:30pm AEST the Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will deliver his second Federal Budget speech live from the House of Representatives. Just after 8pm, Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will join Leigh Sales for his first interview of the night, followed by the response from the Opposition’s Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen. -

Answers to Questions on Notice

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Answers to Senate Estimates Questions on Notice Budget Estimates Hearings May 2015 Communications Portfolio Australian Broadcasting Corporation Question No: 56 Program No. Australian Broadcasting Corporation Hansard Ref: Written, 27/5/2015 Topic: Interviews Senator McGrath, James asked: 1. Why did Sarah Ferguson not apologise after an independent auditor found her interview with Treasurer Joe Hockey to be hostile and a breach of the ABC’s bias guidelines? 2. How does the ABC consider that the interview conducted by the 7.30 Report’s Leigh Sales with Treasurer Joe Hockey after this year’s Budget was fair and unbiased, given that the Treasurer was interrupted 14 times and Ms Sales took up 40 per cent of the interview time? 3. How does the ABC consider that the interview conducted by Lateline’s Emma Alberici with Finance Minister Mathias Cormann after this year’s Budget was fair and unbiased, given that the Finance Minister was interrupted 10 and that Ms Alberici took up one third of the interview time and asserted in the middle of it that the Budget debt figure was ‘nonsense’? Answer: In relation to the 7.30 interview on budget night 2014 between Sarah Ferguson and Federal Treasurer Joe Hockey, the reviewer Colleen Ryan did not find the interview to be in breach of the ABC’s impartiality guidelines. A perception of incivility or aggression by viewers does not necessarily mean that the interviewer is hostile or has failed to demonstrate due impartiality. Ms Ferguson’s interview was tough and tenacious but her approach was even-handed and objective. -

Any Ordinary

About the Book As a journalist, Leigh Sales often encounters people experiencing the worst moments of their lives in the full glare of the media. But one particular string of bad news stories – and a terrifying brush with her own mortality – sent her looking for answers about how vulnerable each of us is to a life- changing event. What are our chances of actually being struck by one? What do we fear most and why? And when the worst does happen, what comes next? In this profound and layered book, Sales talks intimately with people who’ve faced the unimaginable, from terrorism to natural disasters to simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Expecting broken lives, she instead finds strength, hope, even humour. Sales brilliantly condenses the latest research on the way the human brain processes fear and grief, and poses the questions we too often ignore out of awkwardness. Along the way, she offers an unguarded account of her own challenges and what she’s learned about coping with life’s unexpected blows. Introduction Staring at the Sun One That Could Have Been Me Two We’re All in This Together Three The Eye of the Storm Four The Things That Get You Through Five A New Normal Six Out of the Ashes Seven Ordinary Days Notes Acknowledgements In Memory of Joseph Raymond Dale Sales 1948–2018 The very best of dads The day that turns a life upside down usually starts like any other. You open your eyes, swing your body out of bed, eat breakfast, get dressed and leave the house, your mind busy. -

Molly Ringwald, Robert Greene and More

smh.com.au A CRIMINAL , MOLLYMIND RINGWALD & A SEDUCTION WALKARTIST INTO A... HAVE WE GOT A STORY FOR YOU. Tara Moss, Molly Ringwald, Robert Greene and more. Live at Sydney Writers’ Festival May 20–26, 2013. 1HERSA1 S001 2 swf.org.au SYDNEY WRITERS’ FESTIVAL WOULD LIKE TO THANK CORE FUNDERS SUPPORTERS ABL Open Hachette Australia Randwick City Library Service Allen & Unwin HarperCollins Red Room Company Ashfield Library Head On Photo Festival Riverside Theatres Auburn Poets and Writers Group The Hills Shire Library Ryde Library Service Auckland Writers and Readers Service Scholastic Festival History Council of NSW Scribe Australian Poetry Hoopla Simmer on the Bay Australian Publishers Hornsby Central Library South Coast Writers Centre Association Hurstville City Library Stella Prize EXCLUSIVE LEGAL PARTNER Avant Card ICE Sydney Dance Lounge Black Inc Kathy Shand Sydney PEN Blacktown Arts Centre Kogarah Library Sydney Story Factory Blacktown City Libraries Lox & Smith Text Publishing Byteback Computing Macleay Museum The Folio Society Camden Council Library Service Meanjin The Langham Sydney Campbelltown Arts Centre Mont Blanc University of Queensland Press MAJOR PARTNERS Campbelltown City Library Murdoch Media Group University of Technology Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre Museum of Contemporary Sydney Chanelle Collier Art UWA Publishing Chatswood Concourse The Nest Varuna, The Writers’ House Children’s Book Council NSW Writers’ Centre Vivid Ideas of Australia Overland Walker Books City of Sydney Libraries Pan Macmillan The Walkley Foundation -

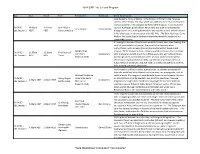

2018 SWF Live & Local Program *THIS PROGRAM IS SUBJECT TO

2018 SWF Live & Local Program Day Start Finish Title Presenter/s Facilitator Event Information Jane Harper’s Force of Nature is the follow-up thriller to the runaway success of her debut, The Dry, which was sold into more than 20 countries and optioned for a film adaption by Reese Witherspoon. It continues the Fri 04/05 - 10.00am 11.00am Jane Harper: story of Australian police officer Aaron Falk, this time as he traces the Jane Harper Claire Nichols L&L Session 1 AEST AEST Force of Nature disappearance of a missing bushwalker who was the crucial whistle-blower in his latest case. In conversation with ABC RN’s The Book Hub host Claire Nichols, the bestselling Australian author talks about the book and her remarkable success. Xi Jinping has become China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong. But with his consolidation of power, the country has become more authoritarian, with increasing censorship and arrests of lawyers and Minglu Chen activists. Three Festival authors uniquely placed to discuss China sit down Fri 04/05 - 11.30am 12.30pm The Future of Xue Yiwei Linda Jaivin with Linda Jaivin to talk about its political, economic and cultural future. L&L Session 2 AEST AEST China Robert E. Kelly Join Minglu Chen, senior lecturer at the Chinese Studies Centre at the University of Sydney; Robert E. Kelly, a professor of political science at Pusan National University; and Xue Yiwei, a prolific Chinese-born novelist, for a riveting and timely discussion. North Korea is unlike any other nation today. Its citizens are sealed off from the world and only allowed access to state-run propaganda, and its Michael Pembroke volatile leader Kim Jong-un is considered a threat to world peace. -

2018 SWF Live & Local Program *THIS

2018 SWF Live & Local Program Day Start Finish Title Presenter/s Facilitator Event Information Jane Harper’s Force of Nature is the follow-up thriller to the runaway success of her debut, The Dry, which was sold into more than 20 countries and optioned for a film adaption by Reese Witherspoon. It continues the Fri 04/05 - 10.00am 11.00am Jane Harper: story of Australian police officer Aaron Falk, this time as he traces the Jane Harper Claire Nichols L&L Session 1 AEST AEST Force of Nature disappearance of a missing bushwalker who was the crucial whistle-blower in his latest case. In conversation with ABC RN’s The Book Hub host Claire Nichols, the bestselling Australian author talks about the book and her remarkable success. Xi Jinping has become China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong. But with his consolidation of power, the country has become more authoritarian, with increasing censorship and arrests of lawyers and Minglu Chen activists. Three Festival authors uniquely placed to discuss China sit down Fri 04/05 - 11.30am 12.30pm The Future of Xue Yiwei Linda Jaivin with Linda Jaivin to talk about its political, economic and cultural future. L&L Session 2 AEST AEST China Robert E. Kelly Join Minglu Chen, senior lecturer at the Chinese Studies Centre at the University of Sydney; Robert E. Kelly, a professor of political science at Pusan National University; and Xue Yiwei, a prolific Chinese-born novelist, for a riveting and timely discussion. North Korea is unlike any other nation today. Its citizens are sealed off from the world and only allowed access to state-run propaganda, and its Michael Pembroke volatile leader Kim Jong-un is considered a threat to world peace. -

The Book Thief

Ryde Library Service Community Book ClubCollection Any Ordinary Day By Leigh Sales First published in 2018 Genre & subject Non-Fiction Life changing events Victims – Australia – Interviews Synopsis As a journalist, Leigh Sales often encounters people experiencing the worst moments of their lives in the full glare of the media. But one particular string of bad news stories - and a terrifying brush with her own mortality - sent her looking for answers about how vulnerable each of us is to a life-changing event... Author biography Leigh Peta Sales was born on 10 May 1973) in Brisbane and attended Aspley State High School. She is a graduate of Deakin University (Master of International Relations) and Queensland University of Technology (Bachelor of Journalism). Upon graduation from QUT she joined the Nine Network before joining ABC Brisbane in 1995. Sales has held positions in national radio current affairs and was New South Wales political reporter covering the 1999 and 2007 state elections and the 2000 Summer Olympics. She was the ABC's national security correspondent from 2006 until 2008 and was based in Sydney. Sales was the network's Washington correspondent from 2001 to 2005, covering stories including the Iraq War, the 2004 presidential election, Guantanamo Bay and Hurricane Katrina. In 2011, Sales was appointed presenter of the ABC's flagship news and current affairs program, 7.30. Sales writes a fortnightly blog called Well-readhead, mostly about books and reading. It includes a list of ten interesting things to read, watch or listen -

ABC NEWS Program Schedule

1 | P a g e ABC NEWS Program Guide: National: Week 19 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 7 May 2017 .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Monday, 8 May 2017 ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Tuesday, 9 May 2017 .......................................................................................................................................... 14 Wednesday, 10 May 2017................................................................................................................................... 17 Thursday, 11 May 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 20 Friday, 12 May 2017 ............................................................................................................................................ 23 Saturday, 13 May 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 26 Marketing Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................... 31 2 | P a g e ABC NEWS -

ABC TV Program Guide: Week 14 Index

ABC TV Program Guide: Week 14 Index 1 | P a g e ABC TV Program Guide: Week 14 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 28 March 2021 ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Monday, 29 March 2021 ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday, 30 March 2021 ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Wednesday, 31 March 2021 ............................................................................................................................... 15 Thursday, 1 April 2021 ........................................................................................................................................ 18 Friday, 2 April 2021 ............................................................................................................................................. 21 Saturday, 3 April 2021 ......................................................................................................................................... 23 2 | P a g e ABC TV Program Guide: Week 14 Sunday 28 March 2021 Program Guide Sunday, 28 March 2021 6:00am rage (CC,PG) Keep the party vibe going with wall-to-wall music