Cross-Boundary Effects of Additional Landlord Licensing in Camden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Borough of Camden March 2021 Detailed Scheme Information

MURPHY’S YARD LONDON BOROUGH OF CAMDEN DETAILED SCHEME INFORMATION MARCH 2021 HYBRID PLANNING APPLICATION The proposals are intended to be submitted in a How do we know that the outline elements will be consistent with the Why is flexibility being sought? vision for the site? Hybrid Planning Application to LB Camden. Due to The proposed uses within the employment uses are envisaged to be the scale of the project, the planning application will A Design Code is being produced which will set out the overarching complementary in order to create a vibrant, sustainable and inviting design principles which later planning applications need to adhere to. workspace environment. We are proposing flexibility within the also be considered by the GLA in addition to statutory workspaces in order to have the ability through the detailed design of This will include elements such as the architectural intent, the delivery these outline plots to develop this narrative more granularly, in order stakeholders. of the heathline, the massing approach, and so on. to curate a successful and dynamic place to work and visit. What is a Hybrid Planning Application? What does this mean for the heights and massing of the buildings in This is a planning application which consists of elements, some of the outline element of the planning application? which are in detail and some in outline. The planning application will be accompanied by parameter plans, which set out the proposed use, maximum mass and maximum heights of the plots. What’s the difference between detail and outline? It is envisaged that different architects will take on the detailed A detailed planning application contains all the information of the applications for different plots in the outline elements. -

Ward Profile 2020 West Hampstead Ward

Ward Profile 2020 Strategy & Change, January 2020 West Hampstead Ward The most detailed profile of West Hampstead ward is from the 2011 Census (2011 Census Profiles)1. This profile updates information that is available between censuses: from estimates and projections, from surveys and from administrative data. Location West Hampstead ward is located to the north-west of Camden. It is bordered to the north by Fortune Green ward; to the east by Frognal and Fitzjohns ward; to the south by Kilburn ward and Swiss Cottage ward; and to the west by the London Borough of Brent. Population The current resident population2 of West Hampstead ward at mid-2019 is 14,100 people, ranking 7th largest ward by population size. The population density is 159 persons per hectare, ranking 7th highest in Camden, compared to the Camden average of 114 persons per hectare. Since 2011, the population of West Hampstead has grown faster than the overall population of Camden (at 17.2% compared with 13.4%), the 3rd fastest growing ward on percentage population change since 2011. 1 Further 2011 Census cross-tabulations of data are available (email [email protected]). 2 GLA 2017-based Projections ‘Camden Development, Capped AHS’, © GLA, 2019. 1 West Hampstead’s population is projected to increase by 1,900 (13.1%) over the next 10 years to 2029. The components of population change show a positive natural change (more births than deaths) over the period of +1,200 and net migration of +600. Births in the wards are forecast to be stable at the current level of 180 a year, while deaths are forecast to increase from the current level of 50, increasing to 60 by 2029. -

Old Hampstead Town Hall 213 HAVERSTOCK HILL, LONDON NW3 4QP

cluttons.com Old Hampstead Town Hall 213 HAVERSTOCK HILL, LONDON NW3 4QP VARIOUS D1 SUITES AVAILABLE TO LET IN GRADE II LISTED BUILDING Various units available up to a maximum of 6,829 SQ FT cluttons.com DESCRIPTION LOCATION ¡ Old Hampstead Town Hall is an impressive, The building is prominently located at the Grade II Listed building of Victorian and junction of Haverstock Hill and Belsize Avenue, Edwardian architectural styles with a striking a short walk from Belsize Park Tube Station. The 20th Century extension at the rear location benefits from a mix of independent boutique retailers, restaurants and coffee shops on ¡ There is an opportunity to lease a variety of Haverstock Hill. small suites within the property which have D1 use and would be well suited as classrooms, AVAILABILITY editing suites, music rooms or studios The available suites can be taken individually or together and are available by way of flexible MPSTEAD ¡ The remainderHA of the building is occupied GADEN SUBURB subleases for a term by arrangement. by a number of performing arts, music and educational bodies and therefore there is TERMS Highgate opportunity for the incoming occupier to On application develop partnerships and collaborations within theGol dproperty.ers Green NEW ORLEANS WALK Crouch Hill OVERGROUND Archway Finsbury Park OVERGROUND FALCONER WALK CHILDS HILL Tufnell Park AMPSTEAD OVERGROUND FORTUNE GREEN H Gospel Oak Holloway Road 213 HAVERSTOCK HILL Finchley Road & Frognal OVERGROUND Belsize Park Caledonian Road OVERGROUND West Hampstead Kilburn OVERGROUND -

Download Directions

DIRECTIONS & LOCATION Maresfield Gardens FITZJOHN’S AVE Blackburn Rd REGAL LONDON FINCHLEY 4–5 Coleridge Gardens, ROAD London, NW6 3QH Belsize Ln College Cres FINCHLEY RD Belsize Park COLLEGE CRES Compayne Gardens Buckland Cres Canfield Gardens Fairhazel Gardens Greencroft Gardens Fairfax Rd SWISS Goldhurst Terrace COTTAGE Fairfax Pl Aberdare Gardens Belsize Rd A41 FINCHLEY RD HILGROVE RD ADELAIDE RD Goldhurst Terrace B525 AVENUE RD SOUTH HAMPSTEAD B509 BELSIZE RD Alexandra Rd St John’s Wood Rd ARRIVING AT ARRIVING AT ARRIVING AT FINCHLEY ROAD SOUTH HAMPSTEAD SWISS COTTAGE Boundary Rd (BY FOOT) (BY FOOT) (BY FOOT) 8 MINS | 0.4 MILES 2 MINS | 500ft 7 MINS | 0.3 MILES Arriving into Finchley Road Tube on theBoundary Rd Turn right out of South HampsteadLoundoun Rd Arriving into Swiss Cottage Tube station on Jubilee Line or Metropolitan Line, take the overground station onto Loudoun Road the Jubilee Line, take Exit 5 towards Belsize station exit and head straight on Finchley Road Road towards a large Waitrose, which will be Cross over Loudoun Road and turn right on your right hand side using the zebra crossing to join Fairhazel Continue straight down Belsize Road, passing Gardens Tesco Express on your left hand side Walk past Waitrose and turn right onto Goldhurst Terrace, continuing all the way Continue along Fairhazel Gardens for At the end of Belsize Road, take the third down this road until you reach a T junction approximately 20 metres and turn left down exit off the roundabout past ‘Zara Café’ into at the end Coleridge Gardens – this -

Sheltered Housing Schemes in Camden Contents

Sheltered housing schemes in Camden Contents Page What is sheltered housing? .........................................................................................3 Other services for older people in Camden ..............................................................4 Other sheltered housing options in Camden ............................................................5 Map of scheme locations and schemes listed alphabetically .................................6 Scheme information .....................................................................................................8 Sheltered schemes listed by area Hampstead and Swiss Cottage Page Number Argenta ...........................................................................................................................9 Henderson Court ..........................................................................................................10 Monro House ................................................................................................................11 Robert Morton House ..................................................................................................12 Rose Bush Court ..........................................................................................................13 Spencer House .............................................................................................................14 Waterhouse Close ........................................................................................................15 Wells Court ...................................................................................................................16 -

Creating Space for Nature: Camden Biodiversity Strategy

Creating space for nature: Camden Biodiversity Strategy Consultation draft Comments can be made at https://camdenbiodiversitystrategy.commonplace.is/ until the 14th May 2021. Contents Vision ......................................................................................................................... 1 What is ‘biodiversity’? ................................................................................................. 1 Why we need nature .................................................................................................. 2 An Ecological Emergency .......................................................................................... 7 The policy, strategy and legislative context .............................................................. 10 What you can do for nature ...................................................................................... 12 The Biodiversity Strategy ......................................................................................... 14 A Nature Recovery Network for Camden .............................................................. 15 The Action Plan ..................................................................................................... 16 The Camden Nature Partnership .......................................................................... 17 Evidence-based decision making .......................................................................... 17 Planning for a changing climate ........................................................................... -

This Document Has Been Superseded by the Euston Station OSD – Memorandum of Information

– OSD been PQQ EUSTONhas STATIONStation DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY CANARY WHARF Euston Information document KING’S CROSS the of by CITY OF LONDON This ST PANCRAS INTERNATIONAL supersededMemorandum EUSTON STATION SOUTH BANK WEST END REGENT’S PARK working together to redevelop Euston – OSD been PQQ has Station Euston The DepartmentInformation for Transport and Network Rail intend to appoint documentthe of a long-term strategic Master Development Partner for the byredevelopment and regeneration of land at Euston Station This one of the largest development opportunities in central London supersededMemorandum – For illustrative purposes only Working together with the local community and– the Master Development Partner, we want to create a Euston that provides a great experience for the community, travellers, businesses and DEVELOPING visitors. Our aim is to generate economic development (including new jobs and homes) above and OSDaround the station and throughout the wider area, as well as to connect people and places across national and high-speed rail networks, London Underground and surface transport. THE VISION been PQQ has Station Euston For illustrative purposes only Inspirational place - Embraces local heritage A centre for thriving localInformation Continues the success and Network of green spaces Gateway to the UK and Europe documentthe communities of growth of the area by This Mixed use district which is a Generates long-term value Stimulates creativity and Promotes accessibility Robust urban framework magnet for business innovation supersededMemorandum – LOCATION OSD CAMDEN Euston Station is situated in the London Borough of Camden, in an area characterised by a diverse mix of uses, including some of London’s most ANGEL prestigious residentialbeen accommodation neighbouring Regent’s Park, premier commercial and office premises, and PQQworld-class educational, research, and HOLBORN cultural institutions. -

Plot T6, King's Cross Central

planning report PDU/2647a/02 15 December 2010 Plot T6, King’s Cross Central in the London Borough of Camden planning application no. 2010/4468/P Strategic planning application stage II referral (new powers) Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008 The proposal Development of student housing (657 bed spaces) in a building of between 14 and 27 storeys, along with a retail unit at ground floor level. The applicant The applicants are King’s Cross General Partner Ltd and Urbanest (UK), and the architect is Glenn Howells Architects Strategic issues This is a full planning application for new student housing, although outline permission for student housing already exists, as part of the wider King’s Cross Central masterplan. There were outstanding transport, design and energy matters from the consultation stage, and the Mayor and Deputy Mayor have also reconsidered the development against tall buildings policies. There are now no outstanding strategic issues. The Council’s decision Camden Council has resolved to grant permission for the development, subject to a section 106 legal agreement and no intervention from the Mayor. Recommendation That Camden Council be advised that the Mayor is content for it to determine the case itself, subject to any action that the Secretary of State may take, and does not therefore wish to direct refusal or direct that he is to be the local planning authority. Context 1 On 7 September 2010, the Mayor of London received documents from Camden Council notifying him of a planning application of potential strategic importance to develop the above site for the above uses. -

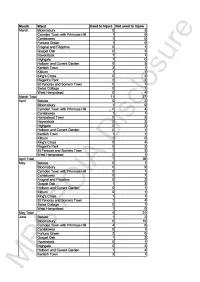

Month Ward Used to Injure Not Used to Injure March Bloomsbury 0 3

Month Ward Used to Injure Not used to injure March Bloomsbury 0 3 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 1 5 Cantelowes 1 0 Fortune Green 1 0 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 1 Gospel Oak 0 2 Haverstock 1 1 Highgate 1 0 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 3 1 Kilburn 1 1 King's Cross 0 2 Regent's Park 2 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 0 1 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 0 4 March Total 11 27 April Belsize 0 2 Bloomsbury 1 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 4 Cantelowes 1 1 Hampstead Town 0 2 Haverstock 2 3 Highgate 0 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kentish Town 1 1 Kilburn 1 0 King's Cross 0 4 Regent's Park 0 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 West Hampstead 0 1 April Total 7 36 May Belsize 0 1 Bloomsbury 0 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 1 Cantelowes 0 7 Frognal and Fitzjohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 1 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kilburn 0 1 King's Cross 1 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 4 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 1 0 May Total 4 31 June Belsize 1 2 Bloomsbury 0 1 0 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 4 6 Cantelowes 0 1 Fortune Green 2 0 Gospel Oak 1 3 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 2 Holborn and Covent Garden 1 4 Kentish Town 3 1 MPS FOIA Disclosure Kilburn 2 1 King's Cross 1 1 Regent's Park 2 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 Swiss Cottage 0 2 West Hampstead 0 1 June Total 18 39 July Bloomsbury 0 6 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 5 1 Cantelowes 1 3 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 2 0 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 4 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 1 0 King's Cross 0 3 Regent's Park 1 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 0 Swiss Cottage 1 2 West -

Swiss Cottage

Swiss Cottage Population: 16,297 Land area: 115.615 hectares December 2015 The maps contained in this document are used under licence A-Z: Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright and database rights OS 100017302 OS: © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OS 100019726 Strengths Social 90.5% of the population do not have a disability or long term health problem (Camden: 85.6%) Economic 71.6% of residents are economically active (Camden: 68.1%) Average annual household income is £60,211 (Camden: £52,962) Significant retail presence Swiss Cottage has a designated town centre Health & Well-being 49% of adults eat healthily (Camden: 41.6%) Knowledge, Skills & Experience 64% of pupils achieved KS4 GCSE 5+ A*-C inc English & maths (Camden: 59.9%) Community Significantly lower total crime rate than the Camden average: 70 (Camden: 124.4) Challenges Social Population density of 141 people per hectare (Camden: 105.4pph) Economic There are 0.7 jobs per capita of working age residents (Camden: 2.1 jobs per capita) The lowest average annual household income is £32,141 (S. Cottage: £60,211; Camden: £52,962 Very little childcare provision - 0.05 places per capita of children under 5 (Camden: 0.27 places) Health & Wellbeing 16% or reception class primary school children are overweight (Camden: 12%) Community Only 64.6% of under 5s are registered with Early Years (Camden: 79%) Multiple deprivation Lower super output areas* that fall within 10% most deprived in England (S. Cottage = 10 LSOAs) Income deprivation (1 LSOA) Health and disability deprivation (5 LSOAs) Living environment deprivation (3 LSOAs) Income deprivation affecting children (1 LSOA) Income deprivation affecting older people (1 LSOA) * A lower super output area is a geography for the collection and publication of small area statistics. -

Ward Profile 2020 Haverstock Ward

Ward Profile 2020 Strategy & Change, January 2020 Haverstock Ward The most detailed profile of Haverstock ward is still from the 2011 Census (2011 Census Profiles)1. This profile updates information that is available between censuses: from estimates and projections, from surveys or from administrative data. Location Haverstock ward is located geographically towards the centre of Camden. It is bordered to the south by Camden Town with Primrose Hill ward; to the east by Kentish Town ward; to the north by Gospel Oak ward and to the West by Belsize ward. Population The projected resident population2 of Haverstock ward at mid-2019 is 13,800 people, ranking 9th by population size in Camden. The population density is 188 persons per hectare, the 4th highest in Camden, compared to the Camden average of 114 persons per hectare. Since 2011, the population of Haverstock has grown at a lower rate to the overall population of th Camden (at 11.5% compared with 13.4%), ranking 12 on percentage growth since 2011. 1 Further 2011 Census cross-tabulations of data are available (email [email protected]). 2 GLA 2017-based Interim Projections ‘Camden Development, Capped AHS’, © GLA, 2019. 1 Haverstock is forecast to grow by 300 residents (2.3%) over the next 10 years to 2029. The components of population change show a positive natural change (more births than deaths) over the period of +700 and a net loss due to migration of -300. Births in the ward are forecast to fall from the current 160 a year to 130 by 2029, while deaths remain stable at around 80 a year. -

HAVERSTOCK HILL RESTAURANT 760 Ft2 for Sale

HAVERSTOCK HILL RESTAURANT 760 ft2 For Sale ■ Good main road trading location in the the ■ Ceramic tiled floors desirable and affluent Haverstock Hill / ■ Spot lighting Belsize Park ■ Commercail kitchen in the basement ■ Good decorative order ■ No VAT ■ electric security shutter frontage ■ 2 modern WC's in basement 152 Haverstock Hill, Hampstead NW3 2AY 174 West End Lane, West Hampstead, London, NW6 1SW t 020 7794 7788 | www.dutchanddutch.com These particulars form no part of any contract. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, this cannot be guaranteed. All rentals and prices are quoted exclusive of VAT. The premises comprise an end of terrace self-contained shop and basement premises in good decorative order currently trading as a retail drycleaners. The shop has the benefit of a newly acquired A3 Restaurant Use. The shop is divided into a front open plan retail area with a passage leading to a room at the rear. There is an internal staircase in the passage area leading to the basement which is divided to form an open plan kitchen area with a cooking range having an overhead extractor as well as a double sink plus 2 modern WC/Washrooms. Amenities include; Electric steel security shutter over shop frontage, spot lighting and ceramic tiled flooring to shop and basement areas. LOCATION ACCOMMODATION The property is situated on a prominent secondary Ground floor main road trading location in the heart of 325 sqft (30 sqm) Hampstead on the northern side of Haverstock Hill close to the junction with Upper Park Road Basement and close to Belsize Park (Northern Line) 425 sqft (40 sqm) Underground Station.