Necrophilia Variations (Pdf) Free Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

Women, Sexuality, and Postfeminism in Post-Growth Japan

Consuming Pleasures: Women, Sexuality, and Postfeminism in Post-Growth Japan (快楽を消費する:成長後の日本における女性、セクシュアリティ、 そしてポストフェミニズム) ハンブルトン アレクサンドラ メイ Alexandra May Hambleton 論文の内容の要旨 論文題目 Consuming Pleasures: Women, Sexuality, and Postfeminism in Post- Growth Japan (快楽を消費する:成長後の日本における女性、 セクシュアリティ、そしてポストフェミニズム) 氏名 HAMBLETON Alexandra May In Japan, as a result of an education system and mainstream media that denies women active sexualities, and the limited success of second wave feminism, the rhetoric of women’s right to sexual pleasure never gained a strong foothold. Second wave feminism made great inroads into legislation, but widespread cultural change remained elusive— particularly in regards to female sexuality. This dissertation is a study of representations of female sexuality in post-growth neoliberal Japan. Based on more than two years of fieldwork conducted in the Tokyo area and discourse analysis of various media I question why feminist conceptualizations of women’s right to pleasure have failed to make inroads in a Japan that clings to a pronatalist, pro-growth ideology as the result of growing anxiety over the country’s economy and future. I examine women’s magazine anan, alternative sex education providers, and the growing number of female-friendly pleasure product companies who are working to change perceptions of female sexuality and contemplate whether their work can be considered feminist. This sector—an example of what Andi Zeisler (2016) has termed “marketplace feminism” may be thoroughly commercialized, yet it also offers a space in which women may explore discourses of sex and pleasure that were not previously available. In Chapter 1, I examine the social conditions of contemporary Japan that deny female pleasure and explain how second wave feminism failed to address desire. -

The Constitutional Status of Morals Legislation

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 98 | Issue 1 Article 2 2009 The onsC titutional Status of Morals Legislation John Lawrence Hill Indiana University-Indianapolis Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Hill, John Lawrence (2009) "The onC stitutional Status of Morals Legislation," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 98 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol98/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TKenf]iky Law Jornal VOLUME 98 2009-2010 NUMBER I ARTICLES The Constitutional Status of Morals Legislation John Lawrence Hiff TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. MORALS LEGISLATION AND THE HARM PRINCIPLE A. Some Difficulties with the Concept of "MoralsLegislation" B. The Near Irrelevance of the PhilosophicDebate C. The Concept of "Harm" II. DEFINING THE SCOPE OF THE PRIVACY RIGHT IN THE CONTEXT OF MORALS LEGISLATION III. MORALS LEGISLATION AND THE PROBLEMS OF RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW A. The 'RationalRelation' Test in Context B. The Concept of a Legitimate State Interest IV. MORALITY AS A LEGITIMATE STATE INTEREST: FIVE TYPES OF MORAL PURPOSE A. The Secondary or IndirectPublic Effects of PrivateActivity B. Offensive Conduct C. Preventingthe Corruptionof Moral Character D. ProtectingEssential Values andSocial Institutions E. -

Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission Handbook

Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission Handbook December 2014 Table of Contents 1. Opening Statement. .................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Working in a historical cemetery. ............................................................................................................ 2 3. Rhode Island General Laws pertaining to Cemeteries. CHAPTER 11-20 Graves and Corpses § 11-20-1 Disinterment of body. .................................................................................................... 3 § 11-20-1.1 Mutilation of dead human bodies – Penalties – Exemptions. ..................................... 3 § 11-20-1.2 Necrophilia. .................................................................................................................. 3 § 11-20-2 Desecration of grave. ...................................................................................................... 4 § 11-20-3 Removal of marker on veteran's grave........................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 19-3.1 Trust Powers § 19-3.1-5 Financial institutions administering burial grounds. ..................................................... 5 CHAPTER 23-18 Cemeteries § 23-18-1 Definitions. ..................................................................................................................... 6 § 23-18-2 Location of mausoleums and columbaria. ..................................................................... 6 -

Of Iowa Code

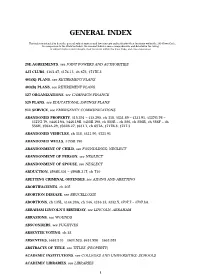

GENERAL INDEX This index is intended to describe general subject matters and law concepts and to identify their locations within the 2014 Iowa Code. In comparison to the Skeleton Index, the General Index is more comprehensive and detailed in the listing of subject matters and concepts, their locations within the Iowa Code, and cross-references. 28E AGREEMENTS, see JOINT POWERS AND AUTHORITIES 4-H CLUBS, §163.47, §174.13, ch 673, §717E.3 401(K) PLANS, see RETIREMENT PLANS 403(B) PLANS, see RETIREMENT PLANS 527 ORGANIZATIONS, see CAMPAIGN FINANCE 529 PLANS, see EDUCATIONAL SAVINGS PLANS 911 SERVICE, see EMERGENCY COMMUNICATIONS ABANDONED PROPERTY, §15.291 – §15.295, ch 318, §321.89 – §321.91, §327G.76 – §327G.79, §446.19A, §446.19B, §455B.190, ch 555B – ch 556, ch 556B, ch 556F – ch 556H, §562A.29, §562B.27, §631.1, ch 657A, §717B.8, §727.3 ABANDONED VEHICLES, ch 318, §321.90, §321.91 ABANDONED WELLS, §455B.190 ABANDONMENT OF CHILD, see FOUNDLINGS; NEGLECT ABANDONMENT OF PERSON, see NEGLECT ABANDONMENT OF SPOUSE, see NEGLECT ABDUCTION, §598B.301 – §598B.317, ch 710 ABETTING CRIMINAL OFFENSES, see AIDING AND ABETTING ABORTIFACIENTS, ch 205 ABORTION DISEASE, see BRUCELLOSIS ABORTIONS, ch 135L, §144.29A, ch 146, §216.13, §232.5, §707.7 – §707.8A ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S BIRTHDAY, see LINCOLN, ABRAHAM ABRASIONS, see WOUNDS ABSCONDERS, see FUGITIVES ABSENTEE VOTING, ch 53 ABSENTEES, §633.510 – §633.520, §633.580 – §633.585 ABSTRACTS OF TITLE, see TITLES (PROPERTY) ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS, see COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES; SCHOOLS ACADEMIC LIBRARIES, see -

Pseudonecrophilia Following Spousal Homicide

CASE REPORT J. Reid Meloy, I Ph.D. Pseudonecrophilia Following Spousal Homicide REFERENCE: Meloy, J. R., "Pseudonecrophilla Following children, .ages 1. and 3, and her common law husband, aged 26. Spousal Homicide," Journal of Forensic Sciences, JFSCA, Vol. 41, No.4, July 1996, pp. 706--708. She was m the hthotomy position with her hips extended and her knees flexed. ABSTRACf: A c.ase of pseudonecrophilia by a 26-year-old male She was nude except for clothing pulled above her breasts. following the mulliple stabbing death of his wife is reported. Intoxi Blood stains indicated that she had been dragged from the kitchen cated wah alco~~J at the .tim~, the man positioned the corpse of approximately seven feet onto the living room carpet. The murder hIS ~~ouse t? faclh!ate vagInal Intercourse with her in the lithotomy weapon, a 14.5 inch switchblade knife, was found in a kitchen posltlon while he viewed soft core pornography on television. Clini drawer. The children were asleep in the bedroom. Autopsy revealed cal interview, a review ofhistory, and psychological testing revealed .. 61 stab wounds to her abdomen, chest. back, and upper and lower dIagnoses of antisocial per~on~lity dis<;>rder and major depression (DSM-IV, Amencan Psychlatnc AssocIation, 1994). There was no extremities, the latter consistent with defensive wounds. Holes in evidence of psychosis, but some indices of mild neuropsychological the clothing matched the wound pattern on the body. Vaginal Impainnent. T~e moti~ations for this rare case ofpseudonecrophilia smears showed semen, but oral and anal smears did not. -

Harmful Effects of Pornography 2016 Reference Guide

Harmful Effects of Pornography 2016 Reference Guide fightthenewdrug.org COPYRIGHT © 2015 by Fight the New Drug, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A certified resource of Fight the New Drug. Fight the New Drug is a 501(c)(3) Non-Profit and was established in March 2009. Please email [email protected] or call us at 385.313.8629 with any questions. Heart — 2.1 How Pornography Warps Expectations.................................................41 2.2 How Pornography Warps Expectations of Sex......................................44 2.3 How Pornography Impacts Partner’s Mental & Emotional Health ......................................46 2.4 How Pornography Changes Perceptions of Partners ................................49 2.5 How Pornography Influences Contents Acquired Sexual Tastes .................................51 2.6 How Pornography Impacts Sexual Intimacy ........................................... 53 2.7 How Pornography Impacts Relationships & Families .............................. 55 Brain 2.8 How Pornography Encourages Objectification ........................................... 58 — 2.9 How Pornography Use Decreases 1.1 Understanding the Brain’s Interest in Actual Partners Reward Center ............................................. 3 & Actual Sex ............................................... 59 1.2 How Pornography Alters 2.10 How Pornography Can Lead Sexual Tastes ................................................. 5 to Physical Danger for Partners .................... 60 1.3 Pornography Induced Erectile Dysfunction (ED) ........................................... -

Relatório Sobre Os Usos E Costumes No Posto Administrativo De Chinga

RELATÓRIO SOBRE OS USOS E COSTUMES NO POSTO ADMINISTRATIVO DE CHINGA [DISTRITO DE MOÇAMBIQUE, 1927] Manuscrito existente no Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique RELATÓRIO SOBRE OS USOS E COSTUMES NO POSTO ADMINISTRATIVO DE CHINGA [DISTRITO DE MOÇAMBIQUE, 1927] Manuscrito existente no Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique Francisco A. Lobo Pimentel RELATÓRIO SOBRE OS USOS E COSTUMES NO POSTO ADMINISTRATIVO DE CHINGA, 1927 Manuscrito existente no Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique Autor: Francisco A. Lobo Pimentel Editor: Centro de Estudos Africanos da Universidade do Porto Actualização de fixação do texto: ex- Comissão para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, Lisboa, 1999 Notas: de rodapé e a actualização da grafia dos vocábulos macua no texto, entre parênteses recto, Eduardo Medeiros. Colecção: e-books Edição: 1.ª (Fevereiro/2009) ISBN: 978-989-8156-13-6 Localização: http://www.africanos.eu Centro de Estudos Africanos da Universidade do Porto. http://www.africanos.eu Preço: gratuito na edição electrónica, acesso por download. Solicitação ao leitor: Transmita-nos ([email protected]) a sua opinião sobre este trabalho. ©: É permitida a cópia de partes deste documento, sem qualquer modificação, para utilização individual. A reprodução de partes do seu conteúdo é permitida exclusivamente em documentos científicos, com in- dicação expressa da fonte. Não é permitida qualquer utilização comercial. Não é permitida a sua disponibilização através de rede electrónica ou qualquer forma de partilha electrónica. Em caso de dúvida ou pedido de autorização, contactar directamente o CEAUP ([email protected]). ÍNDICE Introdução 11 1.0 Raças 41 2.0 Área, geografia e hidrografia 45 Serras 45 Rios 46 3.0 Antropologia 49 4.0 História e cronologia 53 5.0 Divertimentos 55 Batuques só para homens 55 Batuques para homens e mulheres conjuntamente 57 Batuques só para mulheres 60 Batuques de guerra 61 6.0 Marcas de tribos: usos e costumes 63 Vestimenta e adornos 63 7.0 Regime tributário 69 8.0 Instabilidade da população 70 9.0 Instintos guerreiros: armas ofensivas e defensivas 73 10. -

Digital Playlist

Title Artist Title Artist Boogie Wonderland- "Earth, Wind & Fire" Ironic- Alanis Morissette Does Your Mother Know- Abba Thank U Alanis Morissette Fernando- Abba UR Alanis Morissette Knowing Me Knowing You- Abba You Learn Alanis Morissette Lay All Your Love On Me- Abba You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Mamma Mia Abba Black Velvet- Alannah Myles Money Money Money Abba Crying At The Discotheque Alcazar One Of Us Abba Wild 12 Megamix Alex K Ring Ring Abba Amazing Alex Lloyd Rock Me Abba Lucky Star Alex Lloyd S.O.S. Abba Billion Dollar Babies- Alice Cooper Take A Chance On Me Abba I'm Eighteen- Alice Cooper The Name Of The Game Abba School's Out Alice Cooper The Winner Takes It All Abba Under My Wheels Alice Cooper Voulez Vous Abba Back In My Life Alice Deejay Waterloo Abba Better Off Alone- Alice Deejay Absolutely Fabulous absolutely fabulous I Love The Nightlife- Alicia Bridges Are You Ready AC-DC Smooth Criminal Alien Ant Farm Back In Black AC-DC Smooth Criminal(v) Alien Ant Farm Fire Your Guns AC-DC Bootie Call- All Saints Giving The Dog A Bone AC-DC I Know Where It's At- All Saints Goodbye & Good Riddance To Bad Luck AC-DC Never Ever All Saints Got You By The Balls AC-DC Pure Shores All Saints Have A Drink On Me AC-DC Angel Amanda Perez Hells Bells AC-DC Vibe-Rator Amen Highway To Hell(v) AC-DC Angel In My Heart Amen vs Alex K If You Dare AC-DC I Can't Wait Amen vs Alex K Let Me Put My Love Into You AC-DC Knock On Wood- Ami Stewart Let's Make It AC-DC Baby Baby- Amy Grant Mistress For Christmas AC-DC I’m Outta Love- Anastacia Moneytalks -

Overcoming Violence Against Women and Girls the International Campaign to Eradicate a Worldwide Problem

Overcoming Violence against Women and Girls The International Campaign to Eradicate a Worldwide Problem MICHAELL. PENN AND RAHELNARDOS in collaboration with William S. Hatcher and Mary K. Radpour of the Authenticity Project ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham Boulder New York 9 Oxford ROWAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A Member of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group 4720 Boston Way, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowmanlittle field.com PO Box 317 Oxford OX2 9RU, UK Copyright 0 2003 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data PeM, Michael L., 1958- Overcoming violence against women and girls : the international campaign to eradicate a worldwide problem / Michael L. Penn and Rahel Nardos. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7425-2499-X (cloth : alk. paper) - ISBN 0-7425-2500-7 (pbk. : a. paper) 1. Womeu-Violence against. 2. Sex discrimination against women. 3. Women-Violence against-Prevention. 4. Sex discriminationagainst women-Prevention. I. Nardos, Rahel. II. Title. HQ1237 .P45 2003 362,88'082--dc21 2002010307 Printed in the United States of America @ TMThepaper -

Regimes of Truth in the X-Files

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-1999 Aliens, bodies and conspiracies: Regimes of truth in The X-files Leanne McRae Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation McRae, L. (1999). Aliens, bodies and conspiracies: Regimes of truth in The X-files. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ theses/1247 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1999 Aliens, bodies and conspiracies : regimes of truth in The -fiX les Leanne McRae Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation McRae, L. (1999). Aliens, bodies and conspiracies : regimes of truth in The X-files. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Freibert, Finley

Citation: Freibert, Finley. “A Remembrance of Shan Sayles an Innovative Showman and Key Figure in the History of Gay Public Life.” Physique Pictorial: Official Quarterly of the Bob Mizer Foundation, no. 49 (Summer 2019), 85-89. Summary: This article presents a microhistory of Shan Sayles’ entrepreneurship in film exhibition that involved both arthouse and exploitation cinemas. Covering the years up to around 1970, it also functions as a commemoration for Sayles with particular focus on the gay films he acquired for his theaters across the country in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The article was commissioned by the Bob Mizer Foundation for their relaunch of Mizer’s Physique Pictorial as an expansion on my article for The Advocate entitled “Commemorating Two Forgotten Figures of Stonewall-Era Gay Film.” While some of the broader points echo from The Advocate article, this piece does not focus on Monroe Beehler, and instead includes additional original research fleshing out Sayles’ beginnings in arthouse exhibition as well as his later business practices. As of this writing, Physique Pictorial 49 is out-of-print. Note: New figures have been added to the original article text for illustration purposes. Page numbers for the original article text have been preserved from the original. Article text: A Remembrance of Shan Sayles an Innovative Showman and Key Figure in the History of Gay Public Life Author: Finley Freibert On August 19, 2018, San Francisco’s Nob Hill Theatre, one of America’s oldest venues for gay-oriented adult entertainment, shuttered its doors. This unfortunate event marked a culmination of the demise of public venues of pornography that had been sought by public decency campaigns since the mid-20th century and later urban renewal imperatives since the late 1970s.