Drawing Us In: the Australian Experience of Butoh and Body Weather

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PANTOMIME for ACTORS This At-A-Glance Tool Identifies the Exercises, Performance Indicators and Targeted Skills

T H E A T E R — 4 TH GRADE AT-A-GLANCE PLANNING TOOL: PANTOMIME FOR ACTORS This At-A-Glance Tool identifies the exercises, performance indicators and targeted skills. It also includes the assessment strategies I planned for a specific unit (Unit Two), and how I intended to document evidence of learning. Unit II At-A-Glance: Theater (Pantomime) Performance Assessment (*: Main exercises in that session - Bold font: exercise paired with assessment strategy/ies - V: videotaping) UNIT & Performance Indicators New Skill or SESSION EXERCISES or Variation Challenge ASSESSMENT STRATEGIES What are we assessing? 2-One *The Wall preparation/hands placement/in place *The Rope preparation only/posture 2-Two *The Wall in place touch/change The Rope posture, steps 1 & 2 The Tower exploring balance only/V feet 2-Three *The Wall in place TRAVELING *The Tower inclination side to side 2-Four The Wall: with traveling reflection/Self describe and identify *The Rope steps 1-3 step 3 The Tower inclination side to side *Serpentine Movement standing 2-Five *The Rope steps 1-4 step 4 Serpentine Movement standing-head to toe *The Wall with traveling ROTATION 2-Six The Rope The Tower Serpentine Movement standing-head to toe *The Walking steps 1 & 2 2-Seven *The Walking steps 1 & 2 *The Wall with traveling and rotation 2 sides/walls The Tower *The Rope 2-Eight *The Walking steps 1-3 step 3 checklist/Teacher V: steps 1, 2, posture The Tower The Rope The Wall ROTATION 2-Nine *The Walking steps 1-3 step 3 checklist/Peer V: steps 1, 2, posture Serpentine Movement seated The Wall ROTATION accountable Talk/Peer technique and rotation checklist/Teacher V: technique 2-Ten *The Walking steps 1-3 step 3 checklist/Peer steps 1, 2, 3 *Triple steps 1-3, reverse Movements…Head The Rope steps 1-4 checklist/Teacher V: technique 2-Eleven *The Walking steps 1-3 ROTATION Triple steps 1-3, reverse reflection/Self describe and Movements…Head identify RESOURCES: PANTOMIME FOR ACTORS There are a few books on movement and pantomime I recommend. -

The Performance of Gender with Particular Reference to the Plays of Shakespeare

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Dixon, Luke (1998) The performance of gender with particular reference to the plays of Shakespeare. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/6384/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Aro Korol CV 2019:20

FILMMAKER Director / Producer / Editor / Cinematographer MEMBER OF Aro Korol Company Ltd. 71-75 Shelton Street Covent Garden LONDON WC2H 9JQ W: arokorol.com E: [email protected] T: 07729966555 Social Media: @arokorol All the Lonely People 2021 Feature Documentary (Post-Production) Battle of Soho, 2017. Produced, Directed, Filmed and Edited by Aro Korol. This Feature Documentary stars: Actors Stephen Fry and Jenny Runacre, UK club promoter Philip Sallon, UK human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell and, David Bowie and Kate Bush choreographer Lindsay Kemp in his final interview and performance. More at: www.battleofsoho.com Screen in Cinemas: Praise for the film: ★★★★ “Stunning and timely documentary.” Diva Magazine ★★★★ “A rousing documentary.” Total Film ★★★★ “Surprisingly Moving Documentary” The Upcoming Official selection: 33rd Warsaw Film Festival, 2017 Miami Independent Film Festival, 30th Galway Film Fleadh and Netia Off-Camera, 2018 Winner: Hollywood International Independent Documentary Awards, 2017 Available (UK & US) on demand and SVOD: 2021—2016 Freelance - Self Shooting Producer/Director and Editor at Activate Event Management - LONDON. Clients include: Santander, Hyundai, McLaren 2016—2014 Freelance - Self Shooting Producer/Director and Editor at D&D Conferences – LONDON. Clients include: BP, Energizer & Wilkinson. 2014—2009 Video Editor at Monkey AV – LONDON. Technical Skills, Software: Davinci Resolve Studio & Adobe Cameras: (Digital Cinema Cameras, DSLR, 35mm and 16mm Film) Languages: English, French, Polish Creative Credits: -

A Study Guide for Teachers

KAPUT A STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS ABOUT THE STUDY GUIDE Dear Teachers: We hope you will find this Study Guide helpful in preparing your students for what they will experience at the performance of Kaput. Filled with acrobatic thrills and silly blunders, we’re sure Kaput will delight you and your students. Throughout this Study Guide you will find topics for discussion, links to resources and activities to help facilitate discussion around physical theatre, physical comedy, and the golden age of silent films. STUDY GUIDE INDEX ABOUT THE PERFORMANCE RESOURCES AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION 1. About the Performer 1. Be the Critic 2. About the Show 2. Tell a Story Without Saying a Word 3. About Physical Theatre 3. Making a Silent Film 4. About Physical Comedy 4. Body and Expression 5. The Art of the Pratfall 5. Taking a Tour 6. The Golden Age of Silent Films (1894 – 1924) 6. Pass the Ball 7. Physical Comedy + Silent Film = Silent Comedy 7. What’s in a Gesture? Being in the Audience When you enter the theater, you enter a magical space, charged, full of energy and anticipation. Show respect by watching and listening attentively Do not distract fellow audience members or interrupt the flow of performance Applause at the end of the performance is the best way to show enthusiasm and appreciation. About The Performer Tom Flanagan is one of Australia’s youngest leading acrobatic clowns. A graduate of the internationally renowned circus school, The Flying Fruit Flies; Tom started tumbling, twisting, flying and falling at the age of six. -

Vibrations of Emptiness ❙

from Croatian stages: Vibrations of Emptiness ❙ A review of the performance SJENA (SHADOW) by MARIJA ©ΔEKIΔ ❙ Iva Nerina Sibila The same stream of life that runs through my veins One thing is certain, the question about the meaning and night and day runs through the world and dances approach to writing about dance comes to a complete halt in rhythmic measures. when the task at hand is writing about an exceptional per- formance. Such performances offer us numerous forays into It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the world of the author, numerous interpretations and analy- the earth in numberless blades of grass and breaks into ses, as well as reasons why to write about it. I believe that tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers. Shadow, which is the impetus for this text, is one such per- formance. It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death, in ebb and in flow. Implosion of Opposites Travelling within the space of Shadow, we encounter a I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this series of opposite notions. Art ∑ science, East ∑ West, body world of life. And my pride is from the life-throb of ages ∑ spirit, improvisation ∑ choreography, male ∑ female, young dancing in my blood this moment. ∑ old are all dualities that are continuously repeated no mat- Tagore ter which direction the analysis takes. Treated in the pre-text of Marija ©ÊekiÊ and her associ- ates these oppositions do not cancel each other out, do not I recently participated in a discussion on the various ways join together, do not enter into conflict, nor confirm each in which one can write about a dance performance. -

The Sought for Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata's Cultural Rejection And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Waseda University Transcommunication Vol.3-1 Spring 2016 Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies Article The Sought For Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata’s Cultural Rejection and Creation Julie Valentine Dind Abstract This paper studies the influence of both Japanese and Western cultures on Hijikata Tatsumi’s butoh dance in order to problematize the relevance of butoh outside of the cultural context in which it originated. While it is obvious that cultural fusion has been taking place in the most recent developments of butoh dance, this paper attempts to show that the seeds of this cultural fusion were already present in the early days of Hijikata’s work, and that butoh dance embodies his ambivalence toward the West. Moreover this paper furthers the idea of a universal language of butoh true to Hijikata’s search for a body from the “world which cannot be expressed in words”1 but only danced. The research revolves around three major subjects. First, the shaping power European underground literature and German expressionist dance had on Hijikata and how these influences remained present in all his work throughout his entire career. Secondly, it analyzes the transactions around the Japanese body and Japanese identity that take place in the work of Hijikata in order to see how Western culture might have acted as much as a resistance as an inspiration in the creation of butoh. Third, it examines the unique aspects of Hijikata’s dance, in an attempt to show that he was not only a product of his time but also aware of the shaping power of history and actively fighting against it in his quest for a body standing beyond cultural fusion or history. -

Raquel Almazan

RAQUEL ALMAZAN RAQUEL.ALMAZAN@ COLUMBIA.EDU WWW.RAQUELALMAZAN.COM SUMMARY Raquel Almazan is an actor, writer, director in professional theatre / film / television productions. Her eclectic career as artist-activist spans original multi- media solo performances, playwriting, new work development and dramaturgy. She is a practitioner of Butoh Dance and creator/teacher of social justice arts programs for youth/adults, several focusing on social justice. Her work has been featured in New York City- including Off-Broadway, throughout the United States and internationally in Greece, Italy, Slovenia, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala and Sweden; including plays within her lifelong project on writing bi-lingual plays in dedication to each Latin American country (Latin is America play cycle). EDUCATION MFA Playwriting, School of the Arts Columbia University, New York City BFA Theatre Performance/Playwriting University of Florida-New World School of With honors the Arts Conservatory, Miami, Florida AA Film Directing Miami Dade College, Miami Florida PLAYWRITING – Columbia University Playwriting through aesthetics/ Playwriting Projects: Charles Mee Play structure and analysis/Playwriting Projects: Kelly Stuart Thesis and Professional Development: David Henry Hwang and Chay Yew American Spectacle: Lynn Nottage Political Theatre/Dramaturgy: Morgan Jenness Collaboration Class- Mentored by Ken Rus Schmoll Adaptation: Anthony Weigh New World SAC Master Classes Excerpt readings and feedback on Blood Bits and Junkyard Food plays: Edward Albee Writing as a career- -

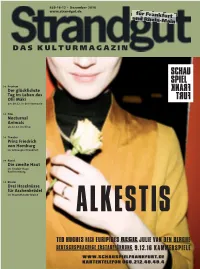

D a S K U L T U R M a G a Z

459-16-12 s Dezember 2016 www.strandgut.de für Frankfurt und Rhein-Main D A S K U L T U R M A G A Z I N >> Preview Der glücklichste Tag im Leben des Olli Mäki am 14.12. in der Harmonie >> Film Nocturnal Animals ab 22.12. im Kino >> Theater Prinz Friedrich von Homburg im Schauspiel Frankfurt >> Kunst Die zweite Haut im Sinclair-Haus Bad Homburg >> Kinder Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel im Staatstheater Mainz ALKESTIS TED HUGHES NACH EURIPIDES REGIE JULIE VAN DEN BERGHE DEUTSCHSPRACHIGE ERSTAUFFÜHRUNG 9.12.16 KAMMERSPIELE WWW.SCHAUSPIELFRANKFURT.DE KARTENTELEFON 069.212.49.49.4 INHALT Film 4 Das unbekannte Mädchen von Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne 6 Nocturnal Animals von Tom Ford 7 Paula von Christian Schwochow 8 abgedreht Sully © Warner Bros. 8 Frank Zappa – Eat That Question von Thorsten Schütte 9 Treppe 41 10 Filmstarts Preview Zwischen Wachen 5 Der glücklichste Tag im Leben des Olli Mäki und Träumen Frank Zappa © Frank Deimel »Nocturnal Animals« von Tom Ford Theater Schon in den ersten Bildern 17 Tanztheater 6 herrscht ein beunruhigender 18 Der Nussknacker im Staatstheater Darmstadt Widerspruch zwischen abstoßender 19 Late Night Hässlichkeit und perfektionistischer in der Schmiere Ästhetik: Zu sehen ist in Zeitlupe wa- 20 Hass berndes Fleisch von alten, grotesk auf den Landungsbrücken 20 vorgeführt fetten Frauenkörpern vor einem Das unbekannte Mädchen 21 Jesus und Novalis leuchtend roten Vorhang. Die Da- bei Willy Praml men sind Teil einer Ausstellung, die 22 Kafka/Heimkehr die Galeristin Susan Morrow (Amy in der Wartburg Wiesbaden 23 Prinz Friedrich von Homburg Adams) kuratiert hat. -

The Routledge Companion to Jacques Lecoq Mime, 'Mimes' And

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 02 Oct 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Companion to Jacques Lecoq Mark Evans, Rick Kemp Mime, ‘mimes’ and miming Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315745251.ch2 Vivian Appler Published online on: 18 Aug 2016 How to cite :- Vivian Appler. 18 Aug 2016, Mime, ‘mimes’ and miming from: The Routledge Companion to Jacques Lecoq Routledge Accessed on: 02 Oct 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315745251.ch2 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 2 MIME, ‘MIMES’ AND MIMING Vivian Appler At the height of the Nazi occupation of Paris, Marcel Carné (1906–96) raised a ghost. His 1945 film,Les Enfants du Paradis (Children of Paradise),1 reconstructs the mid-nineteenth cen- tury Boulevard du Temple (Boulevard of Crime) featuring the French pantomime popularized by Jean-Gaspard Deburau (1796–1846) at le Théâtre des Funambules (the Theatre of Tight- ropes). -

Jacques Lecoq and the Neutral Mask

EMBODYING ENGLISH LANGUAGE: JACQUES LECOQ AND THE NEUTRAL MASK NIKOLE LAUREN PASCETTA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN EDUCATION YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST 2015 ©Nikole Pascetta, 2015 ii ABSTRACT My study explores the process of settlement for Newcomer-to-Canada youth (NTCY) who are engaged in English-language learning (ELL) of mainstream education. I propose the inclusion of a modified physical theatre technique to ELL curricula to demonstrate how a body-based supplemental to learning can assist in improving students’ language acquisition and proficiency. This recognizes the embodied aspect of students’ settlement and integration as a necessary first- step in meaning making processes of traditional language-learning practices. Foundational to this thesis is an exploration of the Neutral Mask (NM), an actors training tool developed by French physical theatre pedagogue Jacques Lecoq. A student of Lecoq (1990- 1992), I understand NM as a transformative learning experience; it shapes the autoethnographic narrative of this study. My research considers the relationship between the body and verbal speech in English-language learning, as mediated by the mask. An acting tool at the heart of Lecoq’s School, the mask values the non-verbal communication of the body and its relationship to verbal speech. My study explains how the mask, by its design, can reach diverse learning needs to offer newcomer students a sense of agency in their language learning process. I further demonstrate how through discussion of an experimental applied practice field study. -

Avila Gillian M 2020 Masters.Pdf (12.22Mb)

REPOSITIONING THE OBJECT: EXPLORING PROP USE THROUGH THE FLAMENCO TRILOGY MARIA AVILA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DANCE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO APRIL, 2020 © MARIA AVILA, 2020 ii Abstract Reflecting on the creation process of my flamenco trilogy, this thesis explores how one can reposition iconic flamenco objects when devising, creating, and producing three short films: The Fan, The Rose and The Bull. Each film examines personal, historical, and local relationships to iconic flamenco objects, enabled through the collaboration with filmmakers: Audrey Bow, Dayna Szyndrowski, and Clint Mazo. iii Dedication I wish to dedicate this thesis to my mother Pat Smith. An inspirational teacher, artist, arts enthusiast, and the most wonderful mother a daughter could ask for. Miss you. iv Acknowledgements The journey to complete my MFA would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. Thank you to my collaborators Audrey Bow, Dayna Szyndrowski, Clint Mazo, Michael Rush, Sydney Cochrane, Bonnie Takahashi, Josephine Casadei, Verna Lee, Adya Della Vella, and Gerardo Avila for contributing your time and your talents. Thank you to my friends and family, you indeed made this all possible. Thank you to Connie Doucette, Adya Della Vella and Gerardo Avila, for your unconditional support. To my love Clint for risking it all and taking this journey with me. Thank you to my welcoming and encouraging classmates Emilio Colalillo, Raine Madison, Natasha Powell, Lisa Brkich, Christine Brkich, Patricia Allison, and Kari Pederson. Thank you to my editor Nadine Ryan for your dedication, enthusiasm and critical eye. -

Here Has Been a Substantial Re-Engagement with Ibsen Due to Social Progress in China

2019 IFTR CONFERENCE SCHEDULE DAY 1 MONDAY JULY 8 WG 1 DAY 1 MONDAY July 8 9:00-10:30 WG1 SAMUEL BECKETT WORKING GROUP ROOM 204 Chair: Trish McTighe, University of Birmingham 9:00-10:00 General discussion 10:00-11:00 Yoshiko Takebe, Shujitsu University Translating Beckett in Japanese Urbanism and Landscape This paper aims to analyze how Beckett’s drama especially Happy Days is translated within the context of Japanese urbanism and landscape. According to Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, “shifts are seen as required, indispensable changes at specific semiotic levels, with regard to specific aspects of the source text” (Baker 270) and “changes at a certain semiotic level with respect to a certain aspect of the source text benefit the invariance at other levels and with respect to other aspects” (ibid.). This paper challenges to disclose the concept of urbanism and ruralism that lies in Beckett‘s original text through the lens of site-specific art demonstrated in contemporary Japan. Translating Samuel Beckett’s drama in a different environment and landscape hinges on the effectiveness of the relationship between the movable and the unmovable. The shift from Act I into Act II in Beckett’s Happy Days gives shape to the heroine’s urbanism and ruralism. In other words, Winnie, who is accustomed to being surrounded by urban materialism in Act I, is embedded up to her neck and overpowered by the rural area in Act II. This symbolical shift experienced by Winnie in the play is aesthetically translated both at an urban theatre and at a cave-like theatre in Japan.