August Petermann and Polar Research E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Security and Mapping in the GDR Map Falsification As A

State Security and Mapping in the GDR Map Falsification as a Consequence of Excessive Secrecy? Archiv zur DDR-Staatssicherheit on behalf of the Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic edited by Dagmar Unverhau Volume 7 LIT Dagmar Unverhau (Ed.) State Security and Mapping in the GDR Map Falsification as a Consequence of Excessive Secrecy? Lectures to the conference of the BStU from 8th –9th March 2001 in Berlin LIT Any opinions expressed in this series represent the authors’ personal views only. Translation: Eubylon Berlin Copy editor: Textpraxis Hamburg, Michael Mundhenk Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. ISBN 3-8258-9039-2 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library © LIT VERLAG Berlin 2006 Auslieferung/Verlagskontakt: Grevener Str./Fresnostr. 2 48159 Münster Tel.+49 (0)251–620320 Fax +49 (0)251–231972 e-Mail: [email protected] http://www.lit-verlag.de Distributed in the UK by: Global Book Marketing, 99B Wallis Rd, London, E9 5LN Phone: +44 (0) 20 8533 5800 – Fax: +44 (0) 1600 775 663 http://www.centralbooks.co.uk/acatalog/search.html Distributed in North America by: Phone: +1 (732) 445 - 2280 Fax: + 1 (732) 445 - 3138 Transaction Publishers for orders (U. S. only): Rutgers University toll free (888) 999 - 6778 35 Berrue Circle e-mail: Piscataway, NJ 08854 [email protected] FOREWORD TO THE ENGLISH EDITION My maternal grandmother liked maxims, especially ones that rhyme. -

NORTH Aberdeen’S Circumpolar Collections

University of Aberdeen Marischal Museum and Special Libraries & Archives NORTH Aberdeen’s Circumpolar Collections Rambles among the fields and fjords, from Thomas Forrester, Norway in 1848 and 1849 (London: Longman, 1850). Lib R 91(481) Fore This view looking up to the Shagtols- Tind, the highest mountain in Norway, reaching the height of 7670 English feet, beneath a bell-shaped snowy valley penetrated into the mountains, and closed by a vast glacier…[the view taken from]… the most splendid fir- forest I have yet met with. An Information Document University of Aberdeen Development Office King’s College Aberdeen Scotland, UK t. +44 (0)1224 272281 f. +44 (0)1224 272271 www.abdn.ac.uk/giving 1 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 3 IDEAS OF THE NORTH Maps 3 Marvels 3 Magicians 4 Monsters 6 An ‘imagined north’ 6 ABERDEEN AND THE ARCTIC Treasures 7 Scientists 7 Explorers 7 Drama in the Arctic 8 Commerce and adventure 8 TRAVEL AND TOPOGRAPHY Orkney and Shetland 10 Russia and Siberia 11 Iceland 12 Scandinavia 13 Northern Japan 14 The American Arctic 15 CONCLUSION 19 HOLDINGS AS INDICATED IN THE TEXT 20 2 A significant number of alumni in the University A cartographic pioneer of the sixteenth century, of Aberdeen’s long history have found that the Gerald Mercator, made a single map of The compass needle drew them to the north. As Lands under the Pole, complete with an explorers, settlers, missionaries, or employees imaginary landmass at the North Pole, while of the Hudson’s Bay Company, graduates of in the seventeenth century, Blaeu’s Regions the two ancient colleges which make up the Beneath the North Pole tries to accommodate modern university have been conspicuous in the latest geographical knowledge with many circumpolar connections. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Sverdrup-Among-The-Tundra-People

AMONG THE TUNDRA PEOPLE by HARALD U. SVERDRUP TRANSLATED BY MOLLY SVERDRUP 1939 Copyright @ 1978 by Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, elec- tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the regents. Distributed by : Scripps Institution of Oceanography A-007 University of California, San Diego La Jolla, California 92093 Library of Congress # 78-60483 ISBN # 0-89626-004-6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are indebted to Molly Sverdrup (Mrs. Leif J.) for this translation of Hos Tundra-Folket published by Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, Oslo, 1938. We are also indebted to the late Helen Raitt for recovering the manuscript from the archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. The Norwegian Polar Institute loaned negatives from Sverdrup's travels among the Chukchi, for figures 1 through 4. Sverdrup's map of his route in the Chukchi country in 19 19/20 was copied from Hos Tundra-Folket. The map of the Chukchi National Okrug was prepared by Fred Crowe, based on the American Geographic Society's Map of the Arctic Region (1975). The map of Siberia was copied from Terence Armstrong's Russian Settlement in the North (1 965) with permission of the Cambridge University Press. Sam Hinton drew the picture of a reindeer on the cover. Martin W. Johnson identified individuals in some of the photographs. Marston C Sargent Elizabeth N. Shor Kittie C C Kuhns Editors The following individuals, most of whom were closely associated with Sverdrup, out of respect for him and wishing to assure preservation of this unusual account, met part of the cost of publication. -

Frederick J. Krabbé, Last Man to See HMS Investigator Afloat, May 1854

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society January 2017 Frederick J. Krabbé, last man to see HMS Investigator afloat, May 1854 William Barr1 and Glenn M. Stein2 Abstract Having ‘served his apprenticeship’ as Second Master on board HMS Assistance during Captain Horatio Austin’s expedition in search of the missing Franklin expedition in 1850–51, whereby he had made two quite impressive sledge trips, in the spring of 1852 Frederick John Krabbé was selected by Captain Leopold McClintock to serve under him as Master (navigation officer) on board the steam tender HMS Intrepid, part of Captain Sir Edward Belcher’s squadron, again searching for the Franklin expedition. After two winterings, the second off Cape Cockburn, southwest Bathurst Island, Krabbé was chosen by Captain Henry Kellett to lead a sledging party west to Mercy Bay, Banks Island, to check on the condition of HMS Investigator, abandoned by Commander Robert M’Clure, his officers and men, in the previous spring. Krabbé executed these orders and was thus the last person to see Investigator afloat. Since, following Belcher’s orders, Kellett had abandoned HMS Resolute and Intrepid, rather than their return journey ending near Cape Cockburn, Krabbé and his men had to continue for a further 140 nautical miles (260 km) to Beechey Island. This made the total length of their sledge trip 863½ nautical miles (1589 km), one of the longest man- hauled sledge trips in the history of the Arctic. Introduction On 22 July 2010 a party from the underwater archaeology division of Parks Canada flew into Mercy Bay in Aulavik National Park, on Banks Island, Northwest Territories – its mission to try to locate HMS Investigator, abandoned here by Commander Robert McClure in 1853.3 Two days later underwater archaeologists Ryan Harris and Jonathan Moore took to the water in a Zodiac to search the bay, towing a side-scan sonar towfish. -

Zeittafel (Gesamt)

Zeittafel (gesamt) Notizbuch: HistoArktis - Zeittafeln Erstellt: 09.03.2017 21:39 Geändert: 09.03.2017 21:40 Autor: [email protected] Beginn Ende Ereignis -330 -330 Pytheas von Massalia, griechischer Seefahrer, Geograph und Astronom begab sich als Erster um 330 v. Chr. nach Norden. 700 800 Besiedlung der Faröer Inseln durch die Kelten. 795 795 Entdeckung Islands durch irische Mönche 870 870 Ottar aus Malangen (Troms) Fahrt ins weiße Meer.(ca. 880 n.Chr). 860 860 Erste Mönche besiedeln Island. 875 875 Erste Sichtung von Grönland durch Gunnbjörn Ulfsson 920 920 Fahrt von Erik (Blutaxt) Haraldsson ins Bjamaland 965 965 Fahrt von Harald Eriksson ebenfalls ins Bjamaland 982 982 Wiederentdeckung Grönlands durch Erik Raude (Erik der Rote). 986 986 Erste dauerhafte Siedlung auf Grönland, (Brattahlid - heute: Qassiarsuk) gegründet von Erik Raude. 986 986 Gefahrvolles Abenteuer im Nordatlantik 990 990 Der Norweger Thorbjörn Vifilsson reiste von Island nach Grönland, dies Fahrt gilt als die erste Expedition seit den Anfängen der Besiedlung durch Erik Raude. 990 990 Norwegische Kolonisten in Südostgrönland 997 997 Sagenhafte Berichte einer Expedition nach Grönland 1001 1002 Leif Eriksson (Der älteste Sohn von Erik Raude) entdeckt die Baffin Insel, Labrador, und Neufundland,er gilt als der Entdecker von Amerika vor Columbus 1012 1013 Zerwürfnisreiche Vinland-Expedition 1026 1026 Die Legende einer norwegischen Handelsreise nach dem weißen Meer 1032 1032 Vom Weißen Meer zur „Eisernen Pforte“ 1040 1040 Adam von Bremen berichtet von der „ersten deutschen -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

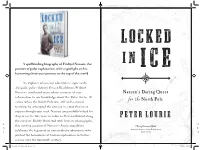

Locked in Ice: Parts

Locked in A spellbinding biography of Fridtjof Nansen, the Ice pioneer of polar exploration, with a spotlight on his harrowing three-year journey to the top of the world. An explorer who many adventurers argue ranks alongside polar celebrity Ernest Shackleton, Fridtjof Nansen contributed tremendous amounts of new Nansen’s Daring Quest information to our knowledge about the Polar Arctic. At North Pole a time when the North Pole was still undiscovered for the territory, he attempted the journey in a way that most experts thought was mad: Nansen purposefully locked his PETER LOURIE ship in ice for two years in order to float northward along the currents. Richly illustrated with historic photographs, -1— —-1 Christy Ottaviano Books 0— this riveting account of Nansen's Arctic expedition —0 Henry Holt and Company +1— celebrates the legacy of an extraordinary adventurer who NEW YORK —+1 pushed the boundaries of human exploration to further science into the twentieth century. 3P_EMS_207-74305_ch01_0P.indd 2-3 10/15/18 1:01 PM There are many people I’d like to thank for help researching and writing this book. First, a special thank- you to Larry Rosler and Geoff Carroll, longtime friends and wise counselors. Also a big thank- you to the following: Anne Melgård, Guro Tangvald, and Jens Petter Kollhøj at the National Library of Norway in Oslo; Harald Dag Jølle of the Norwegian Polar Institute, in Tromsø; Karen Blaauw Helle, emeritus professor of physiology, Department of Biomedicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Carl Emil Vogt, University of Oslo and the Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities; Susan Barr, se nior polar adviser, Riksantikvaren/Directorate for Cultural Heritage; Dr. -

England's Search for the Northern Passages in the Sixteenth And

- ARCTIC VOL. 37, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 1984) P. 453472 England’s Search for the Northern Passages in the Sixteenth and. Early Seventeenth Centuries HELEN WALLIS* For persistence of effort in the. face of adversity no enterprise this waie .is of so grete.avantage over the other navigations in in thehistory of exploration wasmore remarkable than shorting of half the waie, for the other must.saileby grete cir- England’s search for the northern passages to the Far East. .cuites and compasses and .thes shal saile by streit wais and The inspiration for the search was the hope of sharing in the lines” (Taylor, 1932:182). The dangerous part of the.naviga- riches of oriental commerce. In the tropical.regions of the Far tion was reckoned.to .be the last 300 leagues .before reaching East were situated, Roger Barlow wrote in 1541, “the most the Pole and 300 leagues beyond it (Taylor, 1932:181). Once richest londes and ilondes in the the worlde, for all the golde, over the Polethe expedition would choose whetherto sail east- spices, aromatikes and pretiose stones” (Barlow, 1541: ward to the Orient by way of Tartary or westward “on the f”107-8; Taylor, 1932:182). England’s choice of route was backside ofall the new faund land” [NorthAmerica]. limited, however, by the prior discoveries of .Spain and Por- Thorne’s confident .opinion that“there is no lande inhabitable tugal, who by the Treatyof Tordesillas in 1494 had divided the [i.e. uninhabitable€, nor Sea innavigable” (in Hakluyt, 1582: world between them. With the “waie ofthe orient” and ‘The sig.DP) was a maxim (as Professor.Walter Raleigh (19O5:22) waie of the occydent” barred, it seemed that Providence had commented) “fit to be inscribed as a head-line on the charter especially reserved for England. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Journalistic Cartography

ized course in cartography was offered on a regular ba- sis, a rarity at that time. During his career he published what he was to call “the six-six world map giving larger, better continents” (Jefferson 1930). This eliminated J much ocean, allowing larger landmasses, and became popular in the classroom. It is probable that Jefferson taught more than 10,000 Jefferson, Mark Sylvester William. Mark Sylvester students, of whom 80 percent became teachers who fur- William Jefferson was born the seventh child of Daniel ther spread the cartographic habit. Most distinguished and Mary Jefferson on 1 March 1863 in Melrose, Mas- among these students were Isaiah Bowman, R D Calkins, sachusetts. His father, a lover of literature, nurtured the Charles C. Colby, Darrell Haug Davis, William M. Greg- young Mark, who became a member of the class of 1884 ory, George J. Miller, and A. E. Parkins. Of these, Bow- at Boston University. Academic success led to his ap- man, Colby, and Parkins were elected to the presidency pointment (1883–86) as assistant to Benjamin Apthorp of the Association of American Geographers, an honor Gould, director and astronomer of the National Ob- accorded Jefferson in 1916. When Bowman became di- servatory of the Argentine Republic at Cordoba, mem- rector of the American Geographical Society in 1915, he bership in the Argentine Geographical Society (1885), corresponded vigorously with his former teacher, whom and management of a sugar estate in Tucuman Province he invited to head the 1:1,000,000-scale Hispanic map (1886–89). Jefferson returned to Massachusetts, taught project of the Society. -

Études Mongoles Et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques Et Tibétaines, 49 | 2018 the French of the Tundra

Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 49 | 2018 Human-environment relationships in Siberia and Northeast China. Knowledge, rituals, mobility and politics among the Tungus peoples, followed by Varia The French of the Tundra. Early modern European views of the Tungus in translation Les Toungouses, Français de la toundra. Quelques témoignages de l’époque moderne en traduction Jan Borm Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/emscat/3153 DOI: 10.4000/emscat.3153 ISSN: 2101-0013 Publisher Centre d'Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études Electronic reference Jan Borm, “The French of the Tundra. Early modern European views of the Tungus in translation”, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 49 | 2018, Online since 20 December 2018, connection on 13 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/3153 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/emscat.3153 This text was automatically generated on 13 July 2021. © Tous droits réservés The French of the Tundra. Early modern European views of the Tungus in transl... 1 The French of the Tundra. Early modern European views of the Tungus in translation Les Toungouses, Français de la toundra. Quelques témoignages de l’époque moderne en traduction Jan Borm EDITOR'S NOTE Map of the repartition of the Evenki in Russia and China click here 1 “Tous les Toungouses en general sont braves & robustes”, Louis De Jaucourt writes in his entry on Tatars in the 15th volume of the Encyclopédie to which the French Protestant scholar was one of the main contributors (De Jaucourt undated1); that is – “all of the Tungusic peoples are generally brave and robust” – or should we say “courageous and robust2”? Courage is no doubt the notion to be stressed here3.